| Swains Lock | |

|---|---|

Entrance to Swains Lock in 2020 | |

| 39°01′54″N 77°14′37″W / 39.031634°N 77.243531°W | |

| Waterway | Chesapeake and Ohio Canal |

| Country | USA |

| State | Maryland |

| County | Montgomery |

| Operation | Defunct |

| Towpath milemarker 16.7 | |

Swains Lock (Lock 21) and lock house are part of the 184.5-mile (296.9 km) Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (a.k.a. C&O Canal) that operated in the United States along the Potomac River from the 1830s through 1923. It is located at towpath mile-marker 16.7 near Potomac, Maryland, and within the Travilah census-designated place in Montgomery County, Maryland. The lock and lock house were built in the early 1830s and began operating shortly thereafter.

Swains Lock is named after Jesse Swain and his family. Jesse Swain was lock keeper for Lock 21 beginning in 1907, and had been a canal boatman. His father had helped with the canal construction, and his grandson has lived in the house and operated an onsite concession stand into the 21st century. Some of the Swains from Jesse's generation were born on canal boats, and more recent Swains were born in the lock house. Family members lived in the house until 2006, when the house was turned over to the National Park Service.

Today, the lock and restored lock house are part of Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park. Picnic tables at the lock site are located between the Potomac River and the lock house. The lock house is one of seven lock houses on the canal that can be used for overnight stays. It is only a few miles upriver from the Potomac River's Great Falls, and is a few miles downriver from a bird sanctuary.

Background

Ground was broken for construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (a.k.a. C&O Canal) on July 4, 1828.[1] One of the early plans was for the canal to be a way to connect the Chesapeake Bay with the Ohio River—hence the name Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.[2] The canal has several types of locks, including 74 lift locks necessary to handle a 610-foot (186 m) difference in elevation between the two canal ends—an average of about 8 feet (2.4 m) per lock.[3] Including walls, lift locks are 100 feet (30 m) long and 15 feet (4.6 m) wide—usable lockage was closer to 88 feet (27 m) long and 14.5 feet (4.4 m) wide.[3][4] Some canal boats could carry over 110 tons (99.79 metric tons) of coal.[4]

Portions of the canal (close to Georgetown) began operating in the 1830s, and construction ended in 1850 without reaching the Ohio River.[5] Upon completion, the canal ran from Georgetown to Cumberland, Maryland. The canal was necessary since portions of the Potomac River, especially at Great Falls, could not serve for reliable navigation because the river can be shallow and rocky as well as subject to low water and floods.[6] The canal opened the region to important markets and lowered shipping costs. By 1859, about 83 canal boats per week were transporting coal, grain, flour, and farm products to Washington and Georgetown.[7] Tonnage peaked in 1871 as coal trade increased.[8]

The canal faced competition from other modes of transportation, especially the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O Railroad). Starting in Baltimore and adding line westward, the B&O Railroad eventually reached the Ohio River and beyond, while the C&O Canal never went beyond Cumberland in Western Maryland.[1] An economic depression during the mid-1870s, and major floods in 1877 and 1886, put a financial strain on the C&O Canal Company.[8] In 1889, another flood severely damaged the C&O Canal and caused the company to enter bankruptcy.[9] Operations stopped for about two years. Court-appointed trustees recommended by the B&O Railroad took over receivership of the canal and began operating it under court supervision, but canal use never recovered to the peak years of the 1870s.[10] The C&O Canal closed for the season in November 1923.[11] Severe flooding in 1924 prevented the canal from opening in the spring, and the resulting damage from the floods prevented it from opening during the entire year.[12] The flood damage, combined with continued competition from railroads and trucks, caused the shutdown to be permanent.[13] In 1938, the canal was sold to the United States government, and the canal was proclaimed a national monument in 1961.[8]

History

Work on Lock 21 began in July 1829 and was completed in October 1830 at a cost of $8,327.76 (equivalent to $228,857 in 2022).[14] The lock was made from Seneca Creek Red Sandstone boated down the Potomac River from the Seneca Quarry.[15] Construction of the lock house began in May 1831, and was finished in August 1832 at a cost of $765.00 (equivalent to $22,425 in 2022).[16] On August 7, 1830, an individual listed only as "Fuller" was recommended and approved as lock keeper (a.k.a. locktender). His annual compensation was $50 (equivalent to $1,374 in 2022) with the additional benefits of the use of the lock house and the right to use the canal company's land, which was typically used for farming.[17] By June 1832, a 22-mile (35 km) section of the canal was operating between Georgetown and Seneca, which included Lock 21.[18]

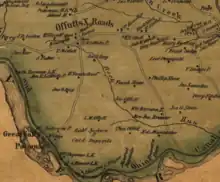

Some C&O Canal records remain, allowing some of the lock keepers to be identified. Mrs. Susan Cross was lock keeper in 1836 until females were banned effective May 1 of that year. Exceptions were made, and most female lock keepers were widows or relatives of the previous keeper.[19] Another early keeper for Lock 21 was Robert C. Fields, who is listed as lock keeper on July 1, 1839.[20] Samuel M. Fisher replaced Fields on May 1, 1846, after an incident at the lock.[21] Fisher was still listed as lock keeper at the end of 1850.[22] Thomas Tarman is listed as Lock 21 tender for 1865.[23] A map of Montgomery County, Maryland, confirms Tarman as the "L.K." (lock keeper) at a point on the canal southwest of Offutt's Crossroads.[24] The name Offutt's Crossroads comes from Edward Offutt, who received a large land grant from Lord Baltimore in 1714. In 1881, the community was renamed Potomac because the Post Office said too many communities had "Crossroads" in their name.[25] Today, Lock 21 (Swains Lock) has a Potomac address and is located in the Travilah census-designated place.[26][27]

The flood of 1889 caused damages to the entire canal estimated to be $1 million (equivalent to $32,570,370 in 2022).[28] In the case of the Lock 21 lock house, the upstream end wall was swept away. Repairs to the house included an addition that had a main floor one foot (0.30 m) lower than the original portion. The house's chimney was enlarged, and another was built on the downstream side. This addition made the house one of the largest lock houses on the canal.[29] John Sipes is listed as the Lock 21 lock keeper in a 1903 newspaper article.[30] He drowned later that year at a lock described as "Gibbs Lock", located "about three miles above the Great Falls".[31]

Swain family

Lock 21, Swains Lock, is named after the Swain family, which has been associated with the C&O Canal since early in its existence.[32] Earlier, the lock had been known as Oak Spring Lock.[33] John T. Swain Sr. was involved in the construction of the C&O Canal and a boatman.[34] Most of his children were born on canal boats.[35] His four sons were all involved with the canal as boatmen or boat captains: John T. Swain Jr., Charles Henry "Hen" Swain, William F. "Bill" Swain, and Jesse A. Swain.[34] The C&O Canal Company eventually transitioned to canal-owned boats—forcing the Swains to leave the shipping business.[36] John Swain Sr. had 15 canal boats that he sold because the canal company would no longer allow them on the canal.[37]

A partial list of canal employees shows a dozen workers named Swain, and many of them were boat captains and a few were lock tenders.[23] Jesse Swain, a boat captain and the youngest of the four sons of John T. Swain Sr., became a lock keeper at Great Falls before moving to Lock 21 in 1907.[38][Note 1] At Lock 21, Jesse and his family supplemented their income by farming on land near the lock house and by driving a wagon of children to school during the offseason.[36] The wagon was pulled by mules and was the first school bus in Potomac.[41] One of Jesse's sons, Otho Oliver Swain, was born on a boat, worked as a boatman, and is thought to be the author of a folk song about the canal.[34][Note 2]

Jesse Swain was the last lock keeper at Lock 21. Before the canal closed to boat traffic, it began transitioning to a place for outdoor recreation. The Swain family continued living at the lock and carried on this transition after the closing by providing canoes for rent. They also ran a concession stand that sold refreshments and fishing supplies.[44] Jesse Swain died in 1939, survived by six of his children.[45] Jesse's son Robert Lee "Bob" Swain and his wife Virginia moved into the lock house after Jesse died, and ran the family business.[35] Bob Swain died in 1967. At that time Frederick "Bubba" Swain and his mother Virginia took over the family business at the lock.[40] Family members continued to live at the lock and run the concession stand until 2006, when it was turned over to the National Park Service.[46]

Today

Today, the Swains Lock and restored lock house are part of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park.[47] Congress authorized the establishment of the park, and acquisition of adjacent land, in 1971.[8] The National Park Service and C&O Trust spell the name of the lock as "Swains" instead of "Swain's", and the road leading to the lock is spelled as "Swains Lock Road".[26]

In 2017, it was decided to renovate the lock house and make it available to the public for overnight stays as part of the Canal Quarters program managed by the C&O Canal Trust.[48] The Swain lock house was restored to be like a typical lock house from 1916, and is one of seven restored lock houses on the C&O Canal.[46][44] Each of the seven restored lock houses in the Canal Quarters program has been restored to a different time period, and all seven are available for overnight stays.[49]

Swains Lock was once thought to be "the most heavily trafficked area on the entire canal". Until 2006, the lock had a concession stand, boat rentals, and bike rentals. It is located between waterfall and water fowl attractions—Great Falls is about 2.5 miles (4.0 km) downstream at towpath mile marker 14.4, and the Dierssen Waterfowl Sanctuary is located about 3.3 miles (5.3 km) upstream at towpath mile marker 20.0.[50][51] The 40-acre (16 ha) Dierssen Waterfowl Sanctuary is a favorite of bird watchers.[51] Both Swains Lock (Lock 21), and the Pennyfield Lock (Lock 22) have also been described as birdwatching "hot spots".[52] The lock has restrooms, parking, picnic tables, and limited tent camping.[26]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Sources differ on the start date for Jesse Swain at Lock 21. The most recent source says "The lock is named for Jesse Swain, appointed lock keeper in 1907."[39] Another source agrees, and says the Swains moved "into lockhouse 21 in 1907".[35] A newspaper says "Jesse Anderson Swain and his family, who had operated Lock 21 since 1909 from the stone lockhouse that went with the job...."[40] Another book quotes one of Jesse Swain's children saying "my father went to tend a lock in 1909".[34]

- ↑ One author speculates that the words to the folk song "Comin' 'Round the Mountain" (different from "She'll Be Coming 'Round the Mountain"), also known as "Otho's Song", describe a trip on the C&O Canal and may have been written by Otho Swain.[42] The C&O Canal Trust believes Swain is the author and lists the words to the song.[43]

Citations

- 1 2 "C&O Canal versus the B&O Railroad". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-06-09. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- ↑ Rubin 2003, p. 4

- 1 2 Unrau 2007, p. 226

- ↑ "Canal History: Canal Era from the 1830s-1870s". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-06-09. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ↑ "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal". Visit Maryland, Maryland Office of Tourism Development. Maryland Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2019-12-28. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ↑ Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 18

- 1 2 3 4 "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2020-08-15. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- ↑ "Chesapeake and Ohio Canal - The C&O Canal's Legal Status 1889-1939". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2020-06-20. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- ↑ "Today in History - October 10 - The C&O Canal". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2020-06-20. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- ↑ "Canal to Close Season in Week". Daily Mail (Hagerstown, Maryland). 1923-11-13. p. 1.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal will be closed this week or early next week for the winter season.

- ↑ "Close C and O Canal". Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland). 1923-08-01. p. 1.

...will not be reopened this year. The canal was damaged by the two floods this spring, and an effort has been made for several months to repair its banks, but with little success.

- ↑ "Canal History: Decline and Eventual Closing of the C&O Canal". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-06-12. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 229

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 159

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 244

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 786

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 65

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 795

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 596

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 799

- ↑ Unrau 2007, p. 620

- 1 2 "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal - Canal Workers". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2020-06-28. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- ↑ Martenet & Bond (1865). Martenet and Bond's Map of Montgomery County, Maryland (Map). Baltimore, Maryland: Simon J. Martenet. Archived from the original on 2020-06-25. Retrieved 2020-06-29.

- ↑ "Maryland Historical Trust Determination of Eligibility Form - Potomac Village Historic District" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland government. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-06. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- 1 2 3 "Lock 21 (Swains Lock)". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-06-13. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- ↑ "Travilah, CDP, Maryland (map)". United States Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau, United States Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2020-07-22. Retrieved 2020-07-22.

- ↑ "Canal History: Flooding and Its Effects on the Canal". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-06-12. Retrieved 2020-07-19.

- ↑ Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, pp. 213–214

- ↑ "Rockville and Vicinity - General and Personal News from Montgomery County's Capital (page 20 far right column)". Washington Evening Star (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1903-05-15. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ↑ "Lock Keeper Drowned (page 12 top)". Washington Times (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1903-09-25. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ↑ U.S. National Park Service Division of Publications 1991, p. 81

- ↑ Romigh, Philip S.; Mackintosh, Barry (1979). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Chesapeake and Ohio Canal". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior (National Archives). Archived from the original on 2020-07-21. Retrieved 2020-07-21.

- 1 2 3 4 Kytle 1996, p. 129

- 1 2 3 "Protecting the Past". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-07-08. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- 1 2 "Protecting the Past". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-07-08. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- ↑ Kytle 1996, p. 131

- ↑ Kytle 1996, p. 138

- ↑ Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 214

- 1 2 Phillips, Angus (1985-01-10). "Life in a Lockhouse On the C&O". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2020-07-14. Retrieved 2020-10-24.

- ↑ Welles 2019, p. 31

- ↑ Hullfish & Ruch 2019, p. 32

- ↑ "Canal by Canoe: Our Campfire Singalong – "Otho (Swain's) Song"". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-07-15. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- 1 2 "Changes at Swains". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-07-08. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ↑ "Jesse A. Swain Dies (page A-14 top right)". Evening Star (Washington) (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). Evening Star. 1939-05-11. Archived from the original on 2020-07-07. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

- 1 2 Fenston, Jacob (2019-06-27). "Wake Up In 1916 When You Stay At This Restored C&O Canal Lockhouse". WAMU. American University Radio. Archived from the original on 2020-07-16. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- ↑ "C&O Canal Hike 10". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2020-06-15. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- ↑ Zimmermann, Joe (2017-08-17). "Swains Lockhouse in Potomac to Be Renovated With National Park Service Grant". Bethesda Magazine. Archived from the original on 2020-07-16. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- ↑ "Canal Quarters". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-07-22. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ↑ Balkan 2008, p. 72

- 1 2 "Dierssen Waterfowl Sanctuary". C&O Canal Trust. Archived from the original on 2020-08-12. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- ↑ Youth 2014, p. 72

References

- Balkan, Evan (2008). The Best in Tent Camping: A Guide for Car Campers Who Hate RVs, Concrete Slabs, and Loud Portable Stereos. Birmingham, Alabama: Menasha Ridge Press. ISBN 978-0-89732-755-8. OCLC 1015877303.

- Hullfish, Bill; Ruch, Dave (2019). The Erie Canal Sings: A Musical History of New York's Grand Waterway. Chicago, Illinois: Arcadia Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-43966-713-2. OCLC 1104726854.

- Kelly, Clare Lise; Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (2011). Places from the Past: The Tradition of Gardez Bien in Montgomery County, Maryland - 10th Anniversary Edition (PDF). Silver Spring, Maryland: Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. ISBN 978-0-97156-070-3. OCLC 48177160. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-12. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Kytle, Elizabeth (1996). Home on the Canal. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-80185-328-9. OCLC 1048227577.

- Lowman, Jeff (2015). Paddling Maryland and Washington, DC : A Guide to the Area's Greatest Paddling Adventures. Guilford, Connecticut: FalconGuides. ISBN 978-1-49301-492-7. OCLC 920824361.

- Rubin, Mary H. (2003). The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-43961-250-7. OCLC 904439352.

- Unrau, Harlan D. (2007). Historic Resource Study: Chesapeake & Ohio Canal (PDF). Hagerstown, Maryland: National Park Service - United States Department of Interior. OCLC 184689456. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-05-09. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- U.S. National Park Service Division of Publications (1991). Chesapeake and Ohio Canal: A Guide to Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park, Maryland, District of Columbia, and West Virginia. Washington, District of Columbia: United States Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780912627434. OCLC 1020193560. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- Welles, Judith (2019). Potomac. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-46710-436-4. OCLC 1111392250.

- Youth, Howard (2014). Field Guide to the Natural World of Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-42141-203-0. OCLC 903126664.