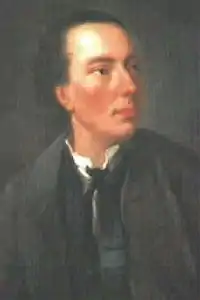

Charles Avison (/ˈeɪvɪsən/; 16 February 1709 (baptised) – 9 or 10 May 1770) was an English composer during the Baroque and Classical periods. He was a church organist at St John The Baptist Church[1] in Newcastle and at St. Nicholas's Church (later Newcastle Cathedral). He is most known for his 12 Concerti Grossi after Scarlatti and his Essay on Musical Expression, the first music criticism published in English. He composed in a transitional style that alternated between Baroque and Classical idioms.

Life

The son of Richard and Anne Avison, Charles Avison was baptised on 16 February 1709,[2] at St John the Baptist Church, in Newcastle. According to The New Grove Dictionary, he was also born in this city.[3] His educational history, though unclear, could have been at one of the two charity schools serving St John's parish. Some sources claim that Charles was the fifth of nine children, while others claim that he was the seventh of ten children. Regardless, Avison was born into a family with a high rate of infant mortality, as many of his siblings died at a young age.[4] His father was a musician and was likely to have been Charles's first teacher. When Charles was 12, his father died, leaving his mother widowed with at least one and possibly two children at home.[4] Avison's adolescent and teenage years are mostly undocumented. One source says he travelled to Italy for study.[5] His education may have included an apprenticeship with a local merchant named Ralph Jenison, a patron of the arts, and later a Member of Parliament, as well as further study of music.[4]

In his twenties, Avison moved to London to further pursue his career as a musician. It was during this period of his life that he met and began to study with Francesco Geminiani.[6] Avison's first documented musical performance was a benefit concert in London on 20 March 1734. This was also his only known concert in London and probably contained some of his early compositions written under Geminiani.[3][4] Avison left London and, on 13 October 1735, was appointed organist of St. John's, Newcastle.[7] This appointment took effect once the church had installed a new organ in June 1736. Avison then accepted a position as organist of St. Nicholas Church in October 1736,[8] and later was appointed director of the Newcastle Musical Society. He remained at these two posts until his death. Avison also taught harpsichord, flute, and violin to private students on a weekly basis.[3] Much of Avison's income was generated through a series of subscription concerts which he helped organise in the North East region of England.[4] These were the first concerts of their type to be held in Newcastle.[9] Despite numerous offers of more prestigious positions later in life, he never again left Newcastle.[9]

Avison was married to Catherine Reynolds on 15 January 1737. The couple had nine children, of whom only three – Jane, Edward, and Charles – survived to adulthood. Edward succeeded his father as both the director of the Newcastle Musical Society and the St Nicholas's organist after his father's death. Charles was also an organist and composer.[3] Avison died in May 1770 of unknown causes, aged 61. According to his will, he had become a very wealthy man between his collection of books, musical instruments, and his stock holdings, which were left to his children. His will specified that he wanted very little money to be spent on his funeral and that he wished to be buried beside his wife at St Andrew's Church, Newcastle upon Tyne where he was buried near the north porch.[4] Avison was one of the subjects in Robert Browning's Parleyings with Certain People of Importance in their Day:[9] "Hear Avison! He tenders evidence/That music in his day as much absorbed/Heart and soul then as Wagner's music now."

Writings

Avison was a bold and controversial author. He is said to have had no fear in expressing his strong ideas with elaborate language, an incredible understanding of music, and a sense of humour. One of the ideas which receives much criticism is his preference for Geminiani and Marcello and his lack of preference for Handel. Although he did praise Handel for his genius, he was not afraid to criticise him either.[8] In addition to his published essays, Avison often wrote lengthy prefaces to his compositions, which have been called “advertisements."[3]

Essay on musical expression

Avison's best-known writing is his Essay on Musical Expression which was originally published in 1752.[10] This essay was written in three parts. The first discusses the effect of music on character and emotion, as well as comparisons of music to painting. Avison states that "A full chord struck, or a beautiful succession of single sounds produced, is no less ravishing to the ear, than just symmetry or exquisite colours to the eye."[10] Avison also discusses in this section the common thought that music reaches all aspects of human emotion. He disagrees with this belief and instead argues that music evokes positive emotions while suppressing the negative ones.[10]

Part II of the essay is a critique of certain composers and their styles. Avison includes a section criticising the emphasis on melody and neglect of harmony as well as the neglect of melody and focus on harmony. For each condition, multiple composers are named in varying degrees to which they offend the balance between these two aspects of music. It is in this section that Avison defines musical expression as a balance between melody and harmony further stating, "Air and Harmony are never to be deserted for the sake of expression: because expression is found on them."[10] Avison does not hold back in expressing his opinion of the composers whom he is criticising. One such passage in the essay exemplifies this: "In these vague and unmeaning pieces, we often find the bewildered composer, either struggling with the difficulties of an extraneous modulation, or tiring the most consummate patience with a tedious repetition of some jejune thought, imagining he can never do enough, till he has run through every key that can be crowded into one movement; till, at length, all his force being exhausted, he drops into a dull close; where his languid piece seems rather to expire and yield its last, than conclude with a spirited, and well-timed cadence."[10]

The third section includes Avison's views on how certain instruments should be used in ensemble performances. This section especially focuses on the concerto, as Avison frequently composed them. He lays out certain guidelines for the use of instruments, such as; "Thus, the Hautboy will best express the Cantabile, or singing style, and may be used in all movements whatever under this denomination; especially those movements which tend to the gay and cheerful."[10]

This essay is often viewed as judgemental and controversial, mostly because of the strong opinions put forth in the section critiquing composers. In January 1753, William Hayes anonymously published Remarks on Mr. Avison’s Essay, which was a review criticising Avison's writing. This writing also contained strong opinions and was more lengthy than Avison's original writing. Avison then published a response to Hayes's writing titled A Reply to the Author of Remarks on the Essay on Musical Expression in February 1753.[3]

Compositions

Avison's best-known compositions are his concerti grossi. They are similar in style to those of Geminiani and change very little across his career. Some were based on existing works by the Italian composer Domenico Scarlatti.[11] Avison placed a lot of emphasis on the importance of melody in his compositions. They are considered to be "unusually tuneful" because of the value which he placed on melody.

Avison also wrote chamber music. His trio sonatas are modelled after the Baroque style. His later chamber works were inspired by Rameau and are keyboard pieces with accompaniment by flute, violin and other instruments. Avison composed a small amount of sacred music including a verse anthem, a hymn and a chant, and a collaborative oratorio with Felice Giardini entitled Ruth.

Orchestral

- Op. 2 Six Concertos (g, Bb, e, D, Bb, D)

- Two Concertos

- Op. 3 Six Concertos – With General Rules for Playing (D, e, g, Bb, D, G)

- Op. 4 Eight Concertos (d, A, D, g, Bb, G, D, c)

- Op. 6 Twelve Concertos (g, Bb, e, D, Bb, D, G, G, D, C, D, A)

- Op. 9 Twelve Concertos: Set 1: (G, D, A, g/G, C, e), Set 2: (Eb, Bb, c, F, A, D)

- Op. 10 Six Concertos (d, F, c, C, Eb, d)

- Twelve Concerti Grossi after Geminiani (without opus number, manuscripts discovered 2000-02, based on Geminiani's op 1 violin sonatas)

- Twelve Concerti Grossi after Scarlatti (1743-44) (without opus number, based on Scarlatti’s keyboard sonatas)

Chamber

- Op. 1 VI Sonatas (chromatic dorian, g, g, dorian, e, D)

- Op. 5 Six Sonatas (G,C, Bb, Eb, G, A)

- Op. 7 Six Sonatas (G, g, Bb, d, a, A)

- Op. 8 Six Sonatas (A, C, D, Bb, g, G)

Other

- "Hast thou not forsaken us" (verse anthem)

- "Glory to God" (Christmas Hymn/Sanctus)

- "Ruth" (oratorio) collab. Giardini (1773)

- "Psalm LVII", chant, Cantico ecclesiastica

Influence

Avison continued the Italian-style tradition, which Francesco Geminiani heavily attributed to his popularity in London. In his Concerti Grossi, in particular, he carried on Geminiani's technique of modelling orchestral concertos after sonatas by older composers. His Essay on Musical Expression criticised Handel, who was much admired in England at the time.[9]

Since 1994 the Avison Ensemble of Newcastle has been performing Avison's music using period instruments.[12]

Newcastle's City Library building which opened in 2009 was named after the composer.[13] The Avison Archive is held at the library.[6]

In April 2014 a play about Avison, written by Sue Hedworth from Ovington, was staged at Gateshead. The play, entitled Mostra, was billed as "a play with live music about our very own 18th Century Newcastle composer".[9]

References

Citations

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Church", St John the Baptist Church, 2014, archived from the original on 29 March 2010, retrieved 6 June 2015

- ↑ "Charles Avison | English composer | Britannica".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Stephens, Norris L. (2014). "Avison, Charles". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Southey, Roz; Maddison, Margaret; Hughes, David (2009). The Ingenious Mr. Avison: Making Music and Money in Eighteenth Century Newcastle. Newcastle upon Tyne: Tyne Bridge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85795-129-5. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ↑ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge Vol II, (1847) London, Charles Knight, p.566.

- 1 2 "Newcastle Collections – Charles Avison". Newcastlecollection.newcastle.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ↑ Robert Hugill (August 2006). "MusicWeb International". avisonensemble.com. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- 1 2 Kingdon-Ward, M. (1951). "Charles Avison". The Musical Times. 92 (1303): 398–401. doi:10.2307/934970. JSTOR 934970.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Whetstone, David (25 April 2014). "Play about Charles Avison takes to the stage in Gateshead". The Journal. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Charles, A; Dubois, P; Hayes, W (2004). Charles Avison's Essay on musical expression: with related writings by William Hayes and Charles Avison. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-75463-460-7.

- ↑ "Avison's Scarlatti stylishly delivered | D Scarlatti Album reviews". Classic FM. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ↑ "The Avison Ensemble". Kings Place. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "City Library | Newcastle City Council". Newcastle.gov.uk. 3 June 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

External links

- Free scores by Charles Avison at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- The Avison Ensemble

- 18th Century English Music short biography

- Discography at classicsonline.com

- Brief biography and discography at naxos.com

- Charles Avison Archived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine at the Newcastle Collection

- Charles Avison – 12 Concertos, Op. 6. – The Avison Ensemble, Pavlo Beznosiuk on YouTube

- Charles Avison – the forgotten master of the North at academyofsaintcecilia.com

- About Charles Avison at avisonensemble.com