Charles G. Dawes | |

|---|---|

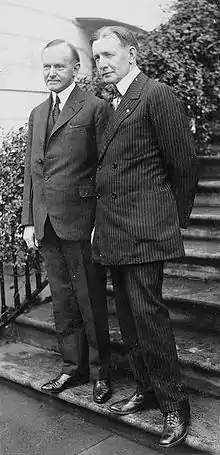

Dawes, c. 1920s | |

| 30th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1925 – March 4, 1929 | |

| President | Calvin Coolidge |

| Preceded by | Calvin Coolidge |

| Succeeded by | Charles Curtis |

| United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom | |

| In office June 15, 1929 – December 30, 1931 | |

| President | Herbert Hoover |

| Preceded by | Alanson B. Houghton |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Mellon |

| 1st Director of the Bureau of the Budget | |

| In office June 23, 1921 – June 30, 1922 | |

| President | Warren G. Harding |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Herbert Lord |

| 10th Comptroller of the Currency | |

| In office January 1, 1898 – September 30, 1901 | |

| President | William McKinley Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | James H. Eckels |

| Succeeded by | William Ridgely |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Charles Gates Dawes August 27, 1865 Marietta, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | April 23, 1951 (aged 85) Evanston, Illinois, U.S. |

| Resting place | Rosehill Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | Marietta College (AB) University of Cincinnati (LLB) |

| Civilian awards | Nobel Peace Prize |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1917–1919 |

| Rank | Brigadier general |

| Unit | American Expeditionary Forces Liquidation Commission of the War Department |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

| Military awards | Army Distinguished Service Medal |

Charles Gates Dawes (August 27, 1865 – April 23, 1951) was an American banker, general, diplomat, musician, composer, and Republican politician who was the 30th vice president of the United States from 1925 to 1929 under Calvin Coolidge. He was a co-recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1925 for his work on the Dawes Plan for World War I reparations.

Born in Marietta, Ohio, Dawes attended Cincinnati Law School before beginning a legal career in Lincoln, Nebraska. After serving as a gas plant executive, he managed William McKinley's 1896 presidential campaign in Illinois. After the election, McKinley appointed Dawes as the Comptroller of the Currency. He remained in that position until 1901 before forming the Central Trust Company of Illinois. Dawes served as a general during World War I and was the chairman of the general purchasing board for the American Expeditionary Forces. In 1921, President Warren G. Harding appointed Dawes as the first director of the Bureau of the Budget. Dawes served on the Allied Reparations Commission, where he helped formulate the Dawes Plan to aid the struggling German economy.

The 1924 Republican National Convention nominated President Calvin Coolidge without opposition. After former Governor of Illinois Frank Lowden declined the vice-presidential nomination, the convention chose Dawes as Coolidge's running mate. The Republican ticket won the 1924 presidential election, and Dawes was sworn in as vice president in 1925. Dawes helped pass the McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Bill in Congress, but President Coolidge vetoed it. Dawes was a candidate for renomination at the 1928 Republican National Convention, but Coolidge's opposition to Dawes helped ensure that Charles Curtis was nominated instead. In 1929, President Herbert Hoover appointed Dawes to be the Ambassador to the United Kingdom. Dawes also briefly led the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which organized a government response to the Great Depression. He resigned from that position in 1932 to return to banking, and died in 1951 of coronary thrombosis.

Early life and family

Dawes was born in Marietta, Ohio, in Washington County, on August 27 1865. son of Civil War General Rufus Dawes and his wife Mary Beman Gates.[1] Rufus had commanded the 6th Wisconsin Regiment of the Iron Brigade from 1863 to 1864 during the American Civil War. His uncle Ephraim C. Dawes was a major who served under Ulysses S. Grant at the Shiloh and Siege of Vicksburg, and was severely wounded at the Battle of Dallas, Georgia, in May 1864.[2]

Dawes's brothers were Rufus C. Dawes, Beman Gates Dawes, and Henry May Dawes, all prominent businessmen or politicians. He had two sisters, Mary Frances Dawes Beach, and Betsey Gates Dawes Hoyt.[3]

Dawes was a descendant of Edward Doty, a passenger on the Mayflower, and William Dawes who rode with Paul Revere to warn American colonists of the advancing British army at the outbreak of the American Revolution.

Dawes married Caro Blymyer on January 24, 1889.[4] They had a son, Rufus Fearing (1890–1912), and a daughter, Carolyn. They later adopted two children, Dana and Virginia.[5]

Education

He graduated from Marietta College in 1884[6] and Cincinnati Law School in 1886.[7] His fraternity was Delta Upsilon.[8]

Early business career

Dawes was admitted to the bar in Nebraska, and he practiced in Lincoln, Nebraska, from 1887 to 1894.[6][9] When Lieutenant John Pershing, the future army general, was military instructor at the University of Nebraska he and Dawes met and formed a lifelong friendship.[10] Pershing also received a law degree at Nebraska and proposed leaving the army to go into private practice with Dawes, who cautioned him against giving up the regular army pay for the uncertainty of legal remuneration.[11] Dawes also met Democratic Congressman William Jennings Bryan. The two became friends despite their disagreement over free silver policies.[12]

Dawes relocated from Lincoln to Chicago during the Panic of 1893.[12] In 1894, Dawes acquired interests in several Midwestern gas plants. He became the president of both the La Crosse Gas Light Company in La Crosse, Wisconsin, and the Northwestern Gas Light and Coke Company in Evanston, Illinois.[5]

Interest in music

Dawes was a self-taught pianist, flutist and composer. His composition Melody in A Major became a well-known piano and violin piece in 1912.[13] Marie Edwards made a popular arrangement of the work in 1921.[14] Also, in 1921, it was arranged for a small orchestra by Adolf G. Hoffmann.[15] Melody in A Major was played at many official functions that Dawes attended.[16]

In 1951, Carl Sigman added lyrics to Melody in A Major, transforming it into the song "It's All in the Game".[16] Tommy Edwards's recording of "It's All in the Game" was a number-one hit on the American Billboard record chart for six weeks in 1958.[17] Edwards's version of the song became number one on the United Kingdom chart that year.[18]

Since then, it has become a pop standard. Numerous artists have recorded versions, including Cliff Richard, the Four Tops, Isaac Hayes, Jackie DeShannon, Van Morrison, Nat "King" Cole, Brook Benton, Elton John, Mel Carter, Donny and Marie Osmond, Barry Manilow, Merle Haggard, and Keith Jarrett.

Dawes is the only vice president to be credited with a number-one pop hit.[16] Dawes and Sonny Bono are the only people credited with a number-one pop hit who were also members of the United States Senate or House of Representatives.[19] Dawes and Bob Dylan (as a writer) are the only persons credited with a number-one pop hit to have also won a Nobel Prize.[lower-alpha 1]

Dawes was a brother of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia.[20]

Early political career

Dawes's prominent positions in business caught the attention of Republican party leaders. They asked Dawes to manage the Illinois portion of William McKinley's bid for the Presidency of the United States in 1896.[21] Following McKinley's election, Dawes was named Comptroller of the Currency, United States Department of the Treasury. Serving in that position from 1898 to 1901, he collected more than $25 million from banks that had failed during the Panic of 1893 and changed banking practices to try to prevent another panic.

In October 1901, Dawes left the Department of the Treasury to pursue a U.S. Senate seat from Illinois. He thought that, with the help of the McKinley Administration, he could win it. McKinley was assassinated and his successor, President Theodore Roosevelt, preferred Dawes's opponent.[22] In 1902, following this unsuccessful attempt at legislative office, Dawes declared that he was done with politics. He organized the Central Trust Company of Illinois, where he served as its president until 1921.[5]

On September 5, 1912, Dawes's 21-year-old son Rufus drowned in Geneva Lake,[23] while on summer break from Princeton University. In his memory, Dawes created homeless shelters in both Chicago and Boston[24] and financed the construction of a dormitory at his son's alma mater, the Lawrenceville School in Lawrenceville, New Jersey.[25]

World War I

.jpg.webp)

Dawes helped support the first Anglo-French Loan to the Entente powers of $500 million. Dawes's support was important because the House of Morgan needed public support from a non-Morgan banker. The Morgan banker Thomas W. Lamont said that Dawes's support would "make a position for him in the banking world such as he otherwise could never hope to make".[26] (Loans were seen as possibly violating neutrality, and Wilson was still resisting permitting loans.)

During WWI, Dawes was commissioned as a major on June 11, 1917, in the 17th Engineers. He was subsequently promoted to lieutenant colonel (July 17, 1917), and colonel (January 16, 1918). In October 1918, he was promoted to brigadier general.[27] From August 1917 to August 1919, Dawes served in France during WWI as chairman of the general purchasing board for the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). His proposal to Gen. Pershing was adopted informed the Military Board of Allied Supply, on which he served as the American delegate in 1918. When the war ended in November, he became a member of the Liquidation Commission of the United States War Department. He was decorated with the Distinguished Service Medal[28] and the French Croix de Guerre in recognition of his service. He returned to the US aboard the SS Leviathan in August 1919.[29] Dawes published a memoir of his World War I service, A Journal of the Great War, 1921.

In February 1921, the U.S. Senate held hearings on war expenditures. During heated testimony, Dawes burst out, "Hell and Maria, we weren't trying to keep a set of books over there, we were trying to win a war!"[30] He was later known as "Hell and Maria Dawes" (although he always insisted the expression was "Helen Maria", an exclamation he claimed was common in Nebraska).[31] Dawes resigned from the Army in 1919[5] and became a member of the American Legion.

1920s: Financing Europe and the Nobel Peace Prize

He supported Frank Lowden at the 1920 Republican National Convention, but the presidential nomination went to Warren G. Harding.[12] When the Bureau of the Budget was created, he was appointed in 1921 by President Harding as its first director. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover appointed him to the Allied Reparations Commission in 1923. Dawes chaired the group that devised the solution to the European crisis: through the Dawes Plan, American banks loaned large sums of money to Germany. The loans helped Germany's industrial production to recover and the government to make reparation payments to France and Belgium as required by the Versailles Treaty. France and Belgium in turn agreed to withdraw the troops that had been occupying the Ruhr since January 1923. In 1929 the Reparations Commission under Owen Young replaced the plan with the more permanent Young Plan, which reduced the total amount of reparations and called for the removal of occupying forces from the Rhineland.[32][33] For his work on the Dawes Plan and the resulting reduction of tensions between France and Germany, Dawes shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1925.[5][34]

Vice presidency (1925–1929)

I should hate to think that the Senate was as tired of me at the beginning of my service as I am of the Senate at the end.

— Charles G. Dawes[35]

At the 1924 Republican National Convention, President Calvin Coolidge was selected almost without opposition to be the Republican presidential nominee.[36] The vice-presidential nominee was more contested. Illinois Governor Frank Lowden was nominated, but declined. Coolidge's next choice was Idaho Senator William Borah, who also declined the nomination. The Republican National Chairman, William Butler, wanted to nominate then-Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover, but he was insufficiently popular. Eventually, the delegates chose Dawes. Coolidge quickly accepted the delegates' choice and felt that Dawes would be loyal to him and make a strong addition to his campaign.[36]

Dawes traveled throughout the country during the campaign, giving speeches to bolster the Republican ticket. On August 22, Dawes would appear at a rally located in Augusta, Maine on the behalf of Republican candidate for Governor Ralph Owen Brewster, who was accused by his opponent William Robinson Pattangall of being backed by the Ku Klux Klan and having sympathies for them. Dawes, who was challenged by Pattangall to talk on the issue, gave a speech attacking the Klan and its religious and racial prejudice rhetoric (Dawes was however careful on how he talked about race).[37] He frequently attacked Progressive nominee Robert M. La Follette as a dangerous radical who sympathized with the Bolsheviks.[12] The Coolidge-Dawes ticket was elected on November 4, 1924, with more popular votes than the candidates of the Democratic and Progressive parties combined.[38] The inauguration was held on March 4, 1925.[39]

Speech to Senate

When Dawes took the oath on March 4, he would take action and infamously go on a tangent against the Senate's Filibuster. In the speech, Dawes criticized rule XXII, calling it "undemocratic" and noted how it was easily taken advantage of due to its two-thirds voting procedure. Through most of the speech, Dawes pointed at specific senators and repeatedly slammed his fist on a table, Chief Justice William Howard Taft writing to his son that the vice president had "made a monkey out of himself." Alongside annoying the entire Senate with a speech that left many shocked, Dawes ended up irritating them again that same day, by having the senators be sworn in one by one (usually they would take the oath in groups). Dawes would end up stealing the thunder from Coolidge that day, many in the press afterwards made a joke out of Dawes, Coolidge was very upset on how the vice president was starting off his term.[40]

Nomination of Charles B. Warren

On March 10, the Senate debated the president's nomination of Charles B. Warren to be United States Attorney General. In the wake of the Teapot Dome scandal and other scandals, Democrats and Progressive Republicans objected to the nomination because of Warren's close association with the Sugar Trust. At midday, six speakers were scheduled to address Warren's nomination. Desiring to take a break for a nap, Dawes consulted the majority and minority leaders, who assured him that no vote would be taken that afternoon. After Dawes left the Senate, all but one of the scheduled speakers decided against making formal remarks, and a vote was taken. When it became apparent that the vote would be tied, Republican leaders hastily called Dawes at the Willard Hotel, and he immediately left for the Capitol. The first vote was 40-40, a tie which Dawes could have broken in Warren's favor. While waiting for Dawes to arrive, the only Democratic senator who had voted for Warren switched his vote. The nomination then failed 41-39—the first such rejection of a president's nominee in nearly 60 years.[35] This incident was chronicled in a derisive poem, based on the Longfellow poem "Paul Revere's Ride"; it began with the line, "Come gather round children and hold your applause for the afternoon ride of Charlie Dawes." The choice of poem was based on Charles Dawes being descended from William Dawes, who rode with Paul Revere.

Dawes and Coolidge became alienated from one another. Dawes declined to attend Cabinet meetings and annoyed Coolidge with his attack on the Senate filibuster. Dawes championed the McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Bill, which sought to alleviate the 1920s farm crisis by having the government buy surplus farm produce and sell that surplus in foreign markets. Dawes helped ensure the passage of the bill through Congress, but President Coolidge vetoed it.[12]

In 1927, Coolidge announced that he would not seek re-election. Dawes again favored Frank Lowden at the 1928 Republican National Convention, but the convention chose Herbert Hoover.[12] Rumors circulated about Dawes being chosen as Hoover's running mate. Coolidge made it known that he would consider the renomination of Dawes as vice president to be an insult. Charles Curtis of Kansas, known for his skills in collaboration, was chosen as Hoover's running mate.[41]

Post-vice presidency (1929–1951)

Court of St. James's and the RFC

After Dawes completed his term as vice president, he served as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom (known formally as the Court of St. James's) from 1929 to 1931.[42] Overall, Dawes was an effective ambassador, as George V's son, the future Edward VIII, later confirmed in his memoirs. Dawes was rather rough-hewn for some of his duties, disliking presenting American débutantes to the King. On his first visit to the royal court, in deference to American public opinion, he refused to wear the customary Court dress, which then included knee breeches. This episode was said to upset the King, who had been prevented by illness from attending the event.

As the Great Depression continued to ravage the US, Dawes accepted President Herbert Hoover's appeal to leave diplomatic office and head the newly created Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). After a few months, Dawes resigned from the RFC. As chairman of the failing Central Republic Bank and Trust Company of Chicago, he felt obligated to work for its rescue. Political opponents alleged that, under Dawes's leadership, the RFC had given preferential treatment to his bank. This marked the end of Dawes's career in public service. For the 1932 election, Hoover considered the possibility of adding Dawes to the ticket in place of Curtis, but Dawes declined the potential offer.[43]

Later in 1932, Dawes and associates formed the City National Bank and Trust Co. to take over the deposits of the failed Central Republic Bank and Trust Company.[44] In 1936, Republican congressional leaders informally approached Dawes about the possibility of heading up their presidential ticket at that year's presidential election, hoping for a candidate associated with the prosperous Coolidge years, but Dawes had no interest in returning to front-line politics; the (ultimately unsuccessful) ticket would instead be headed by Alf Landon.[43]

Later life

_and_Caro_Dana_Dawes_(1866%E2%80%931957)_at_Rosehill_Cemetery%252C_Chicago.jpg.webp)

Dawes served for nearly two decades as chairman of the board of City National from 1932 until his death.[45] He died on April 23, 1951, at his Evanston home from coronary thrombosis at the age of 85.[46] He is interred in Rosehill Cemetery, Chicago.[47]

Personal life

Dawes belonged to several lineage societies and veterans' organizations. These included the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Sons of the American Revolution, General Society of Colonial Wars, American Legion, and Forty and Eight.[48] Dawes was also a member of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts from 1925 until his death in 1951[49]

Honors

- In 1925, Dawes was a co-winner of the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on WWI reparations.[50]

A Chicago public school located at 3810 W 81st Place is named in his honor, as are an Evanston public school at 440 Dodge Avenue and Evanston's Dawes Park at 1700 Sheridan Road.

United States military awards

Distinguished Service Medal citation:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Army Distinguished Service Medal to Brigadier General Charles G. Dawes, United States Army, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished services to the Government of the United States, in a duty of great responsibility during World War I. General Dawes rendered most conspicuous services in the organization of the General Purchasing Board as General Purchasing Agent of the American Expeditionary Forces and as the Representative of the U.S. Army on the Military Board of Allied Supply. His rare abilities, sound business judgment, and aggressive energy were invaluable in securing needed supplies for the Allied armies in Europe. (War Department, General Orders No. 12 (1919))

Foreign honors

- Companion of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom)

- Commander of the Legion of Honor (France)

- Commander of the Order of Leopold (Belgium)

- Croix de Guerre with palm (France)

Legacy

According to Annette Dunlap, Dawes was:

a self-made man who valued hard work and thriftiness tempered with Christian generosity. He spent his life promoting solid Republican values of small government with restrained budgets. Franklin Roosevelt’s philosophy of big government spending was anathema to him.[51]

In 1944, he bequeathed his lakeshore home in Evanston to Northwestern University for the Evanston Historical Society (later renamed the Evanston History Center). Dawes lived in the house until his death. The Dawes family continued to occupy it until the death of Mrs. Dawes in 1957. Since then, the Evanston History Center operates out of the house and manages it as a museum. Designated a National Historic Landmark, the Charles G. Dawes House is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Selected writings

- Dawes, C. G. (1894). The Banking System of the United States and Its Relation to the Money and the Business of the Country. Chicago: Rand McNally.

- ———— "The Sherman Anti-Trust Law: Why It has Failed and Why It Should Be Amended". The North American Review 183.597 (1906): 189–194.

- ———— (1915). Essays and Speeches. New York: Houghton.

- ———— (1921). Journal of the Great War. 2 vols. New York: Houghton. online copy vol 1; also online copy v2

- ———— (1923). The First Year of the Budget of the United States. New York: Harper. online copy

- ———— (1935). Notes as Vice President, 1928–1929. Boston: Little, Brown. online copy

- ———— (1937). How Long Prosperity? New York: Marquis.

- ———— (1939). Journal as Ambassador to Great Britain. New York: Macmillan. online copy

- ———— (1939). A Journal of Reparations. New York: Macmillan. online copy

- ———— (1950). A Journal of the McKinley Years. Bascom N. Timmons (Ed.). La Grange, IL: Tower.

See also

- List of covers of Time magazine (1920s) – December 14, 1925

- List of members of the American Legion

Notes

- ↑ Dylan, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016, wrote "Mr. Tambourine Man", a No. 1 hit for the Byrds.

References

- ↑ Dunlap, Annette B. (2016). Charles Gates Dawes: a Life. Northwestern University Press and the Evanston History Center. p. 12. ISBN 9780810134195.

- ↑ Magnusen, Steve - cite book title: To My Best Girl, 2020, GoToPublish.

- ↑ Gates Dawes Ancestral Lines

- ↑ "The religion of Charles G. Dawes, U.S. Vice-President". www.adherents.com. Archived from the original on February 15, 2006. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Davis, Henry Blaine Jr. (1998). Generals in Khaki. Raleigh, NC: Pentland Press, Inc. p. 103. ISBN 1571970886.

- 1 2 Dunlap, Annette B. Charles Gates Dawes: a Life. p. 17.

- ↑ Dunlap, Annette B. Charles Gates Dawes: a Life. p. 18.

- ↑ Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (February 1884). "Alumni of Delta U". The Delta Upsilon Quarterly. Indianapolis, IN: Delta Upsilon Fraternity. p. 48 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Dunlap, Annette B. Charles Gates Dawes: a Life. pp. 20–38.

- ↑ Dunlap, Annette B. Charles Gates Dawes: a Life. pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Smythe, Donald (1973). Guerrilla Warrior: The Early Life of John J. Pershing. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Charles G. Dawes, 30th Vice President (1925–1929)". US Senate. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ Dawes, Charles Gates. Melody [in A major] for violin with piano acc. Chicago: Gamble Hinged Music, 1912. OCLC 21885776

- ↑ Dawes, Charles Gates, and Marie Edwards. Melody. Chicago, Ill: Gamble Hinged Music Co, 1921. OCLC 10115887

- ↑ Dawes, Charles Gates, and Adolf G. Hoffmann. Melody, small orchestra. Chicago: Gamble Hinged Music Co, 1921. OCLC 46679677

- 1 2 3 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Joel Whitburn, The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits, revised and enlarged 6th edition (New York: Billboard Publications, 1996), 201.

- ↑ (Hatfield 1997: 360)

- ↑ Whitburn, Joel (2004). Top R&B/Hip-Hop Singles: 1942–2004. Record Research. p. 539.

- ↑ "The Vice President Who Wrote a Hit Song". August 16, 2011.

- ↑ Davis, Jr., Henry Blaine (1998). Generals in Khaki. Pentland Press, Inc. p. 81. ISBN 1571970886. OCLC 40298151

- ↑ (Waller 1998: 274)

- ↑ "Charles Gates Dawes Timeline – Evanston History Center". Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Let's Talk It Over". The National Magazine. 46 (September): 905. 1917. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Dawes House Dedicated.; Lawrenceville School Building Partly Financed by Ambassador". The New York Times. November 29, 1929.

- ↑ Merchants of Death Revisited Mises Institute p. 61

- ↑ The New York Times. October 4, 1918.

- ↑ "Valor awards for Charles G. Dawes".

- ↑ The New York Times. August 7, 1919.

- ↑ Dunlap, Annette B. Charles Dawes Gates: a Life. p. 144.

- ↑ "Vice President Dawes". Forbes Library. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ↑ Dunlap, pp. 214–15.

- ↑ Stephen A. Schuker, The End of French Predominance in Europe: The Financial Crisis of 1924 and the Adoption of the Dawes Plan (U of North Carolina Press, 1976).

- ↑ "Charles G. Dawes". The Nobel Prize. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- 1 2 Hatfield, M. O. (1997). Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993. Senate Historical Office. Washington: United States Government Printing Office

- 1 2 Hatfield 1997: 363

- ↑ Dunlap, Annette (September 15, 2016). Charles Gates Dawes: A Life. Northwestern University Press. pp. 192–195. ISBN 978-0-8101-3419-5.

- ↑ Hatfield 1997: 364

- ↑ Reviews, C.T.I (October 16, 2016). American Foreign Relations, A History. p. 193. ISBN 9781619066649. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ↑ Dunlap, Annette (September 15, 2016). Charles Gates Dawes: A Life. Northwestern University Press. pp. 202–204. ISBN 978-0-8101-3419-5.

- ↑ Mencken, Henry Louis; George Jean Nathan (1929). The American Mercury. p. 404.

- ↑ Dunlap, Annette B. Charles Gates Dawes: a Life. pp. 221–44.

- 1 2 Witcover, Jules (2014). The American Vice Presidency. Smithsonian Books. p. 296.

- ↑ "Dawes's New Bank Opens in Chicago; City National and Trust Has $4,000,000 Capital and $1,000,000 Surplus. In Old Bank's Offices Institution Formed by Taking Over Some Departments of Central Republic". The New York Times. October 7, 1932.

- ↑ "Dawes, Charles Gates – Biographical Information". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on September 15, 1999. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Charles G. Dawes, Ex-Vice President, Dies (April 24, 1951)". September 15, 2023.

- ↑ Rumore, Kori (October 4, 2022). "Buried in Chicago: Where the famous rest in peace". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ "The What and the Why of the Forty and Eight". The American Legion Weekly. Vol. 7, no. 38. Indianapolis, Indiana: The American Legion. September 18, 1925. p. 7. ISSN 0886-1234 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ History of the AHAC, Boston, MA (membership roles and accession card)

- ↑ Dunlap, Annette B. Charles Gates Dawes: a Life. pp. 178–79.

- ↑ Cited in Indiana Magazine of History, (2018) 114(1) p. 76.

Bibliography

- Dunlap, Annette B. (2016). Charles Gates Dawes: a Life. Northwestern University Press and the Evanston History Center. ISBN 9780810134195. online review of scholarly biography

- Goedeken, Edward A. "Charles Dawes and the Military Board of Allied Supply". Journal of Military History 50.1 (1986): 1–6.

- Goedecken, Edward A. (1985). "A Banker at War: The World War I Experiences of Charles Gates Dawes". Illinois Historical Journal. 78 (3): 195–206. JSTOR 40191858.

- Goedecken, Edward (November 1987). "Charles G. Dawes Establishes the Bureau of the Budget, 1921-1922". The Historian. 50 (1): 40–53. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1987.tb00734.x. JSTOR 24446946.

- Haberman, F. W. (Ed.). (1972). Nobel Lectures, Peace 1901–1925. Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishing.

- Hatfield, Mark O. (1997). "Vice Presidents of the United States Charles G. Dawes (1925–1929)" (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- Pixton, John E. "Charles G. Dawes and the McKinley Campaign". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 48.3 (1955): 283–306.

- Pixton, J. E. (1952). The Early Career of Charles G. Dawes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sherman, Richard G. (1965). "Charles G Dawes, a Nebraska Businessman, 1887-1894: The Making of an Entrepreneur" (PDF). Nebraska History. 46: 193–207. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.* Timmons, B. N. (1953). Portrait of an American: Charles G. Dawes. New York: Holt; popular biography online copy

- Waller, R. A. (1998). The Vice Presidents: A Biographical Dictionary. Purcell, L. E. (Ed.). New York: Facts On File.

- Davis, Henry Blaine Jr. (1998). Generals in Khaki. Raleigh, NC: Pentland Press. ISBN 1571970886. OCLC 40298151.

- Zabecki, David T.; Mastriano, Douglas V., eds. (2020). Pershing's Lieutenants: American Military Leadership in World War I. New York, NY: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-3863-6.

External links

- Charles G. Dawes on Nobelprize.org

- "Charles G. Dawes Archive" Archived July 30, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Finding aid for the Charles G. Dawes archival collection

- Evanston History Center, headquartered in the lakefront Dawes house

- United States Congress. "Charles G. Dawes (id: D000147)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.. Retrieved 2009-05-14

- Notes As Vice President 1928–1929 by Charles G. Dawes

- Portrait Of An American by Charles G. Dawes

- Newspaper clippings about Charles G. Dawes in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Image of Vice President Charles Dawes during a visit to Los Angeles, 1925. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.