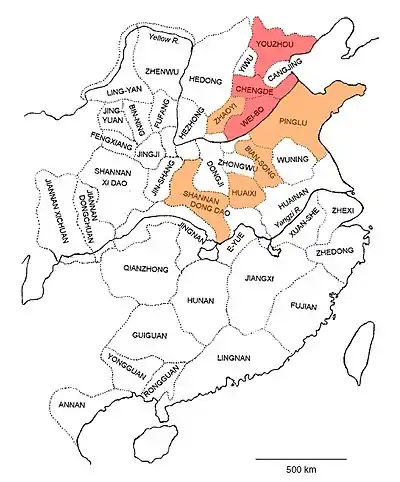

Chengde (成德), situated in modern Shijiazhuang, was an independent Chinese polity in the post-An Lushan Rebellion (755-763) Tang dynasty. The former generals of An Lushan allied with each other to negotiate the existence of their independent realms in northeast China.

History

The adopted son of An Lushan, Li Baochen of Kumo Xi stock, surrendered to the Tang in order to keep control of Chengde. Baochen entered marriage alliances with Tian Chengsi of Weibo and Li Zhengji of Pinglu (Tai'an). The alliance with Tian ended in 775 when Baochen's nephew accidentally caused the death of Tian's son in a game of polo. Baochen joined a coalition force of jiedushi and Tang imperial forces against Tian, but eventually turned on them. Tian ceded Cangzhou to Baochen. Near the end of his life, Baochen started killing the most powerful officers in his army so that they would not be able to contest the succession of his son, Li Weiyue. He also became superstitious, believing that sorcerers could grant him long life and supreme power. In 781, the sorcerers made him a potion that was supposed to prolong his life, but he died three days after drinking it.[1] Emperor Dezong of Tang refused to recognize Weiyue as military governor and declared him a renegade. Weiyue began suffering military defeats until his officer, Wang Wujun, killed him in 782.[2]

However both Wang Wujun and Zhu Tao of Youzhou (who had sided with the Tang court) were disappointed in the rewards they received for their service and rebelled against the Tang in 782. By the end of the year, the jiedushi of Huaixi, Li Xilie, had also rebelled, cutting off the Bian Canal.[3] In 784, Dezong pardoned Wang Wujun, who then turned against Zhu Tao and defeated him on 29 May.[4] Wujun died in 801 and was succeeded by his son Shizhen. Having suffered great difficulties on his father's campaigns, Shizhen was more inclined to peace and actively submitted tribute to the Tang court. He died in 809 and was succeeded by his son Wang Chengzong.[5] Emperor Xianzong of Tang ordered Chengzong to surrender Dezhou and Dizhou (Binzhou) to be formed into a new circuit. Chengzong initially agreed to the demand but later refused to have one of his relatives assigned to the prefectures. The Tang attacked Chengde but the campaign ended in failure and the two prefectures were returned to Chengde in 810.[6] In 815, Xianzong issued an edict calling on Chengzong to repent. Another campaign against Chengde was called but most of the forces did not advance far and were defeated. The campaign was called off in 817. When Wu Yuanji of Huaixi (Zhumadian) was defeated by Tang forces, Chengzong became fearful of his position and surrendered Dezhou and Dizhou as well as sent his sons to the Tang as hostages in return for imperial recognition. Chengzong died in 820 and his brother, Wang Chengyuan, succeeded him. However Chengyuan did not want to rule Chengde. He sent secret communications to Emperor Muzong of Tang, ceding Chengde to Tang control. Chengyuan was transferred to Yicheng Circuit (Anyan), then Fufang (Yan'an), Fengxiang (Baoji), and finally Pinglu (moved to Weifang). He died in 834. It was said that he was lenient and gracious, governing well wherever he went.[1]

The court appointed governor of Chengde, Tian Hongzheng, was killed by the Uyghur Wang Tingcou in 821. Tingcou's family had served as cavalry officers in Chengde since the time of Li Baochen. Tang forces as well as Tian Hongzheng's son Tian Bu attacked Tingcou but failed to make it past the first key outpost, at which point their supplies ran out. Tingcou aided the rebel Li Tongjie against Tang forces. After the defeat of Li Tongjie in 829, Tingcou was pardoned. He died in 834 and was succeeded by his son Wang Yuankui. Although still maintaining independence, Yuankui offered tribute to the Tang court, a change from his father's stance of outright defiance. To reward Yuankui, Emperor Wenzong of Tang sent his cousin, Princess Shouan the daughter of Li Wu (sixth son of Emperor Xianzong), to marry Yuankui in 837. Yuankui participated in the Tang campaign against Zhaoyi (Changzhi). He died in 854 and was succeeded by his son Wang Shaoding. Shaoding exhibited inappropriate behavior such as heavy drinking and had a habit of slinging pellets at people from atop towers for fun. Before the soldiers could remove him, he died in 857, and his younger brother Wang Shaoyi became governor. It was said that Shaoyi was simple and lenient. Both soldiers and the common people were happy under his rule. He died in 866 and was succeeded by Shaoding's son, Wang Jingchong.[1] Jingchong had a good relationship with the imperial court due to his lineage, being descended from Princess Shouan. He contributed troops to the suppression of both Pang Xun and Huang Chao's rebellions. Jingchong died in 883 and was succeeded by his nine-year-old son, Wang Rong.[7][8]

Aftermath

Wang Rong went on to found the state of Zhao, which was destroyed in 921 when he was killed in a coup by his adopted son Zhang Wenli, who in turn died soon after. Wenli's son Zhang Chujin was captured by Li Cunxu the next year. The people of Zhao hated the Zhang family and requested that his family be turned into minced meat. Chujin was dismembered at the marketplace.[9][10]

References

- 1 2 3 Old Book of Tang, vol. 142 Archived 2008-06-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 227.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 235.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 236.

- ↑ New Book of Tang, vol. 211 Archived 2009-02-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 237.

- ↑ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 255.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 229.

- ↑ Davis 2004, p. xxxii.

- ↑ Davis 2004, p. 328.

Bibliography

- Davis, Richard L. (2004), Historical Records of the Five Dynasties

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Routledge

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War: Military practice in seventh-century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0810860537