.jpg.webp)

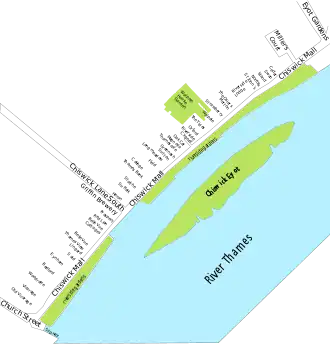

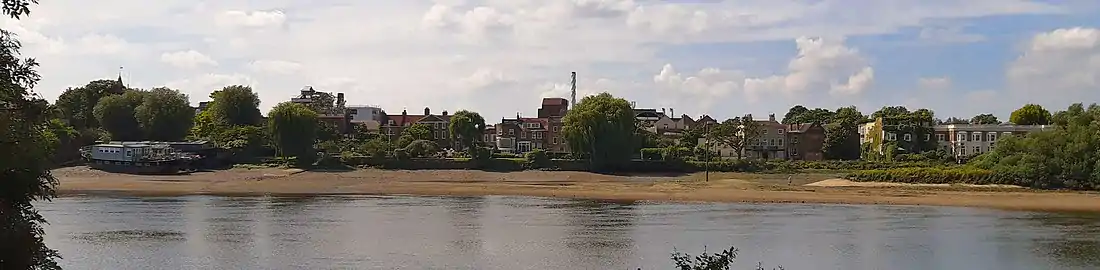

Chiswick Mall is a waterfront street on the north bank of the river Thames in the oldest part of Chiswick in West London, with a row of large houses from the Georgian and Victorian eras overlooking the street on the north side, and their gardens on the other side of the street beside the river and Chiswick Eyot.

While the area was once populated by fishermen, boatbuilders and other tradespeople associated with the river, since Early Modern times it has increasingly been a place where the wealthy built imposing houses in the riverside setting.

Many of the houses are older than they appear, as they were given new facades in the 18th or 19th century rather than being completely rebuilt; among them is the largest, Walpole House. St Nicholas Church, Chiswick lies at the western end; the eastern end reaches to Hammersmith. The street, which contains numerous listed buildings, partially floods at high water in spring tides.

The street has been represented in paintings by artists such as Lucien Pissarro and Walter Bayes; in literature, in Thackeray's novel Vanity Fair; and in film and television, including in the 1955 Breakaway, the 1961 Victim, and the 1992 Howards End.

History

Early origins

Chiswick grew as a village in Anglo-Saxon times from smaller settlements dating back to Mesolithic times in the prehistoric era.[1] Roman roads running east–west along the lines of the modern Chiswick High Road and Wellesley Road met some 500 metres north of Chiswick Mall; the High Road was for centuries the main road westwards from London, while goods were carried along the river Thames.[2]

St Nicholas Church, Chiswick was built in the twelfth century,[2] and by 1181, the settlement of Chiswick had grown up "immediately east" of the church.[1] The prebendal manor house belonging to the church was founded circa 1100 as a stone building; it was demolished around 1710, and is now the site of College House and other buildings. Local trades included farming, fishing, boatbuilding, and operating a ferry across the river.[2][3]

Changing land use

The area was described by John Bowack, writing-master at Westminster School, in 1705; he wrote that "the greatest number of houses are stretched along the waterside from the Lyme kiln near Hammersmith to the Church, in which dwell several small traders, but for the most part fishermen and watermen who make up a considerable part of the inhabitants of this town."[4]

The street was part of a rural riverside village until late in the nineteenth century; the 1865 Ordnance Survey map[5] shows orchards to the north and west of Old Chiswick. The area to the north had become built up with streets of terraced housing by 1913, as shown on the Ordnance Survey map of that date.[6] The Great West Road crossed Brentford in 1925 and Chiswick in the 1950s, passing immediately north of Old Chiswick and severing it from the newer commercial and residential centre around Chiswick High Road.[7]

The naturalist Charles John Cornish, who lived in Orford House on Chiswick Mall,[8] wrote in 1902 that the river bank beside Chiswick Eyot had once been a "famous fishery"; he recorded that "perhaps the last" salmon was caught between the eyot and Putney in 1812, and expressed the hope that if the "purification" of the river continued, the salmon might return.[9]

Setting

Chiswick Mall is a waterfront street on the north bank of the river in the oldest part of Chiswick. It consists of a row of "grand houses"[10][3] providing "Old Chiswick's main architectural distinction"; the street has changed relatively little since 1918.[1] The houses, mainly from the Georgian and Victorian eras, overlook the street on the north side; their gardens are on the other side of the street, beside the river. St Nicholas Church, Chiswick lies at the western end; the eastern end reaches to Hammersmith. Just to the north of the row of grand houses is Fuller's Brewery, giving the area an industrial context. The street and the gardens partially flood at high water in spring tides. Chiswick Mall forms part of the Old Chiswick conservation area; the borough's appraisal of the conservation area describes it as "a remnant of a riverside village for wealthy landowners".[10] The name "Mall" was most likely added in the early 19th century after the model of the fashionable Pall Mall in Westminster.[1]

Grand houses

Medieval period

British History Online states that the prebendal manor house and its medieval neighbours must have been reached by a road that ran eastwards for an unknown distance beside the river from the ferry, and that this eventually became Chiswick Mall.[1]

In 1470, Robert Stillington, Chancellor of England and bishop of Bath and Wells had a "hospice" with a "great chamber" by the Thames in Chiswick.[1]

Early Modern period

The vicarage house at the corner of Church Street and Chiswick Mall had been built by 1589–90. The prebendal manor house was extended to accommodate Westminster School in around 1570.[1] There appears to have been a group of "imposing" houses on Chiswick Mall in the Early Modern period, including a large house on the site of Walpole House, since by 1706 John Bowack wrote of "very ancient" houses beside the river at Chiswick.[1] A house on the site of Bedford House was inhabited by the Russell family in around 1664; it and others nearby were later rebuilt.[1]

17th century

The largest, one of the finest,[3] and most complicated of the grand houses on Chiswick Mall is the Grade I[11] Walpole House. Parts of it, behind the later facade, were according to the historian of buildings Nikolaus Pevsner constructed late in the Tudor era, whereas the visible parts are late 17th and early 18th century. It has three storeys, of brown bricks with red brick dressings. The front door is in a porch with Corinthian pilasters standing on plinths; above is an entablature. Its windows have double-hung sashes topped with flat arches.[12][13] In front of the house is an elegant[13] Grade II* listed screen and wrought iron gate;[13] the gateposts are topped with globes. Its garden is listed in the English Heritage Register of Parks and Gardens.[12]

Walpole House was the home of Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland, a mistress of King Charles II, until her death in 1709; it was later inherited by Thomas Walpole, for whom it is now named.[13] From 1785 to 1794 it served as a boarding house; one of its lodgers was the Irish politician Daniel O'Connell.[3] In the early 19th century it became a boys' school, its pupils including William Makepeace Thackeray. The actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree owned the house at the start of the 20th century. It was then bought by the merchant banker Robin Benson; over several generations the Benson family designed and then restored the garden.[13]

18th century

Morton House was built in 1726 of brown bricks. Its garden is listed in the English Heritage Register of Parks and Gardens.[12] Its former owner, Sir Percy Harris, had a relief sculpture depicting the resurrection of the dead made by Edward Bainbridge Copnall for the garden in the 1920s; the sculpture now serves as his tombstone a short distance away in St Nicholas Churchyard.[14]

The Grade II* Strawberry House was built early in the 18th century and given a new front of red bricks with red dressings around 1730. It has two main storeys with a brick attic above. The front doorway is round-headed; it has a door with six panels, topped with a fanlight decorated with complex tracery. The door is in a porch with cast iron columns; above the porch is a balcony of wrought iron. At the back of the house on the first floor is an oriel window.[12][15] Its garden is listed in the English Heritage Register of Parks and Gardens.[12] Arabella Lennox-Boyd suggested that the garden was used by the botanist Joseph Banks to grow the plant species he had discovered.[16] The walled garden was remodelled in the 1920s by the house's then owner, Howard Wilkinson and his son the stage designer Norman Wilkinson.[15]

The former Red Lion inn, now called Red Lion House, was built of brick;[17] it was licensed as an inn by 1722[1] for Thomas Mawson's brewery just behind the row of houses, now the Griffin Brewery. It was conveniently placed to attract passing trade from thirsty workers from the Mall's draw dock, where boats unloaded goods including hops for the brewery and rope and timber for the local boatbuilders. Inside, it has a handsome staircase; its sitting room is equipped with two fireplaces and decorated above with a frieze in plasterwork showing bowls of punch.[18] At a later date it was given a stucco facade with a six-panelled door under a fanlight, and double-hung sash windows with surrounds.[17]

Of the same period is the Grade II pair of three-storey brown brick houses, Lingard House, with a dormer, and Thames View. Above their doors are door hoods supported by brackets.[17] Also early 18th century is the brown brick with red dressings Grade II Woodroffe House, which was at that time of two storeys; its third story was added late in that century.[17]

A large house, started in 1665 as the house of the Russell family, then the earls of Bedford,[3] but with an 18th-century front, is now divided into Eynham House and the Grade II* Bedford house. The latter has a Grade II gazebo in its garden.[17] The actor Michael Redgrave lived in Bedford House from 1945 to 1954.[3]

The Grade II Cedar House and Swan House were built late in the 18th century; both are three storey buildings of brown brick. Their windows are double-hung sashes with flat arches.[19]

Two more three-storey Grade II 18th century houses are those named Thamescote and Magnolia; the latter has glazing bars on its windows, with iron balconettes on its second floor.[17]

The house called The Osiers was built late in the 18th century but has a newer facade.[20]

19th century

An early 19th-century pair are the Grade II, three-storey Riverside House and Cygnet House. They are built of brown bricks and have porches with a trellis. Another Grade II house of the same era is the two-story Oak Cottage; it has a stucco facade, a moulded cornice, and pineapple finials on its parapet.[21]

Another pair of the same period are the Grade II Island House and Norfolk House. They are faced in stucco, and have three storeys and double-hung sash windows. Their basements have a rusticated facade, while the grand first and second storeys are adorned with large Corinthian pilasters. At the centre, they have paired Ionic columns supporting a balcony with a balustrade; to either side, the windows on the first floor are adorned with pilasters and topped with a pediment.[22]

The house called Orford House and The Tides are a Grade II pair; they were built by John Belcher in 1886. Orford House has timber framing in its gables, while The Tides has hanging tiling there.[21] Belcher also designed Greenash in Arts and Crafts style, with tall chimneys and high gables for the local shipbuilder, Sir John Thorneycroft.[17]

The medieval[1] prebendal manor house was replaced in 1875 with a row of houses. They are decorated with many architectural details such as fruity swags.[lower-alpha 1] They are not all in a line, but all are the same height with a balustrade along the parapet.[17]

20th century

Dan Mason, owner of the Chiswick Soap Company, bought Rothbury House in 1911; it lay at the eastern end of Chiswick Mall, for the Chiswick Cottage Hospital. The house was used for staff quarters, administration, and kitchens. The main hospital block was built in the ¾ acre garden; it had two ten-person wards on the ground floor, one male, one female, and a ward for twelve children upstairs; the whole hospital was constructed and equipped at Mason's expense. A third building housed the outpatients department. The main entrance was on Netheravon Road (to the north), with a second entrance on the Mall. By 1936 the buildings were obsolete, and Mason's nephew, also called Dan Mason, laid the foundation stone for a more modern hospital on 29 February 1936; the new building was finished by 1940. In 1943 it was requisitioned by the Ministry of Health, and it became the Chiswick Maternity Hospital. This closed in 1975. It was then used for accommodation for Charing Cross Hospital, and as a film set, including for the BBC TV series Bergerac and Not the Nine O'clock News. From 1986 it served as Chiswick Lodge, a nursing home for patients with dementia or motor neurone disease; it closed in 2006, and the building was demolished in 2010, to be replaced by housing.[23]

In culture

In painting

The street has been depicted by a variety of artists. The Tate Gallery holds a 1974 intaglio print on paper by the artist Julian Trevelyan[lower-alpha 2] entitled Chiswick Mall.[25] Around 1928, the musician James Brown made an oil painting entitled Chiswick Mall from Island House;[lower-alpha 3] he had been tutored in oil painting by the impressionist painter Lucien Pissarro, who lived for a time in Chiswick.[26] The Victoria and Albert Museum has a 1940 pen and ink and watercolour painting by the London Group artist Walter Bayes with the same title.[27] Mary Fedden, the first woman to teach painting at the Royal College of Art, made an oil on board painting called Chiswick Mall of a woman feeding geese just in front of Chiswick Eyot.[28]

In literature

In English literature, the street features in the first chapter of Thackeray's 1847–48 novel Vanity Fair. The book begins:

While the present century was in its teens, and on one sunshiny morning in June, there drove up to the great iron gate of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, on Chiswick Mall, a large family coach, with two fat horses in blazing harness, driven by a fat coachman in a three-cornered hat and wig, at the rate of four miles an hour. ... as he pulled the bell at least a score of young heads were seen peering out of the narrow windows of the stately old brick house. Nay, the acute observer might have recognized the little red nose of good-natured Miss Jemima Pinkerton herself, rising over some geranium pots in the window of that lady’s own drawing-room.

— Vanity Fair, chapter 1

In film

Henry Cass's 1955 detective thriller film Breakaway involves a houseboat on Chiswick Mall; the Rolls-Royce driven by 'Duke' Martin (Tom Conway) stops in front of the Mill Bakery, now Miller's Court.[29] The 1961 thriller Victim, set in Chiswick, has its barrister protagonist, Melville Farr, played by Dirk Bogarde, living on Chiswick Mall; Melville walks through St Nicholas Churchyard, and meets his wife Laura (Sylvia Syms) in front of his house.[30][31][32] William Nunez's 2021 The Laureate, about the war poet Robert Graves (Tom Hughes), features a barge on Chiswick Mall.[33]

The scene in the 1992 Merchant Ivory film of E. M. Forster's Howards End, where Margaret (Emma Thompson) and Helen (Helena Bonham Carter) stroll with Henry (Anthony Hopkins) in the evening, was shot on Chiswick Mall.[34]

Series One of the BBC's The Apprentice was filmed in the first-floor drawing room "Galleon Wing" extension, of Sir Nigel Playfair's Said House; the room features a large curved plate-glass window giving views up and down the river.[35][36]

Open Gardens

Some of the properties on Chiswick Mall, including Bedford, Eynham, and Woodroffe Houses, from time to time offer access to their private gardens on the National Garden Scheme "Open Gardens" days.[37][38]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 BHO 1982, pp. 54–68.

- 1 2 3 4 Hounslow 2018, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Clegg 2021.

- ↑ Wisdom, James (1985). "Riverside Crafts & Industries". Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ Hounslow 2018, p. 9, map overprinted with Conservation Area outline.

- ↑ Hounslow 2018, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Hounslow 2018, pp. 13, 17.

- ↑ "Orford House". Buildington. Retrieved 4 March 2020.. Cornish lived in Orford House in 1900 (. The Zoologist, 4th series, vol 4, issue 711 (September, 1900). 1900. pp. 438–439 – via Wikisource.) and in 1902 ("Orford House". Panorama of the Thames. Retrieved 4 March 2020.).

- ↑ Cornish, C. J. (1902). The naturalist on the Thames. London: Seeley. p. 68. OCLC 3251979. Archived from the original on 22 August 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- 1 2 Hounslow 2018, p. 6.

- ↑ Hounslow 2018, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hounslow 2018, pp. 17, 21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Walpole House". Historic England. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ Historic England. "Tombstone to Sir Percy Harris, Bart, St Nicholas Churchyard (1096142)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- 1 2 "Strawberry House". Historic England. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ↑ Lennox-Boyd, Arabella (1990). Private Gardens of London. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 152–157. ISBN 978-0297830252.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hounslow 2018, p. 22.

- ↑ "Red Lion, Chiswick Mall". Panorama of the Thames. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ↑ Hounslow 2018, pp. 17, 20.

- ↑ Hounslow 2018, p. 17.

- 1 2 Hounslow 2018, p. 21.

- ↑ Hounslow 2018, pp. 17, 20–21.

- ↑ Bartram, Dorothy (2011). "The History of Chiswick Hospital". Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ↑ "St Peter's Wharf". Panorama of the Thames. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ↑ "Julian Trevelyan 1910-1988 Chiswick Mall 1974". Tate Gallery. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ "Chiswick Mall from Island House, c.1928". Messums London. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ "Chiswick Mall. Artist: Walter John Bayes". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ↑ "Mary Fedden RA (1915 -2012) Chiswick Mall". Panter & Hall. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ↑ "Breakaway". Reelstreets. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ↑ "When Dirk Bogarde Filmed In Chiswick". Chiswick W4.com. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ↑ Nicholson, Ben (17 October 2018). "In search of the locations for the Dirk Bogarde thriller Victim". British Film Institute. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ↑ MacPherson, Lucinda (11 February 2019). "LGBT+ History Month celebrates diversity". The Chiswick Calendar. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ↑ "William Nunez Shares His Thoughts On The Laureate". Vingt Sept Magazine. 30 March 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ↑ Pym, John (1995). Merchant Ivory's English Landscape: Rooms, Views and Anglo-Saxon Attitudes. Harry N. Abram. p. 93. ISBN 978-0810942752.

- ↑ "Buildings". Cambridge 2000. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

4647, Said House, Chiswick Mall, Chiswick, LB Hounslow, Darcy Braddell, c1935

- ↑ "Nominations not proposed for the local list" (PDF). London Borough of Hounslow. 1987. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

Said House evolved from a small C18th gardener's cottage in the Victorian period. It was enlarged and 'Georgianised' in the 1930s. It is unclear whether this was detailed by the designer Mrs Darcy Braddell or by Albert Randall Wells (1877–1942), an English Arts and Crafts architect. It was then that the 'galleon' west wing was created. The extensive 1930s makeover which included the giant curved plate-glass window on the first floor was carried out for the actor-manager Sir Nigel Playfair (1874-1935), who was manager of the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, and lived here between 1931 and 1934. Viscount Davidson, Chairman of the Conservative Party (1927-30) and later Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, lived here from 1956 with his wife, a Member of Parliament who became an early life peeress as Baroness Northchurch of Chiswick. The house was featured as the 'home' for the contestants of the first series of the television programme The Apprentice in 2005.

- ↑ "Open Gardens - Bedford House, Eynham House and Woodroffe House". Open Gardens. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ↑ "Chiswick Mall Gardens". National Garden Scheme. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

General sources

- Bolton, Diane K.; Croot, Patricia E. C.; Hicks, M. A. (1982). "Chiswick: Growth". In T. F. T. Baker; C. R. Elrington (eds.). A History of the County of Middlesex, Volume 7, Acton, Chiswick, Ealing and Brentford, West Twyford, Willesden. London: British History Online. pp. 54–68.

- Clegg, Gill (2021). "Grand Houses". Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- Hounslow (November 2018). OLD CHISWICK: Conservation Area Appraisal: Consultation Draft (PDF). London Borough of Hounslow.

External links

- Panorama of the Thames - view of Chiswick Mall, starting from St Nicholas Church

%252C_Chiswick_Mall_(cropped).jpg.webp)

%252C_Chiswick_Mall.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)