Christianity in Cornwall began in the 4th or 5th century AD when Western Christianity was introduced as in the rest of Roman Britain. Over time it became the official religion, superseding previous Celtic and Roman practices. Early Christianity in Cornwall was spread largely by the saints, including Saint Piran, the patron of the county. Cornwall, like other parts of Britain, is sometimes associated with the distinct collection of practices known as Celtic Christianity[1] but was always in communion with the wider Catholic Church. The Cornish saints are commemorated in legends, churches and placenames.

Unlike Wales, which produced Bible translations into Welsh, the churches of Cornwall never produced a translation of the Bible in the Cornish language. (This may have contributed to that language's demise.) During the English Reformation, churches in Cornwall officially became affiliated with the Church of England. In 1549, the Prayer Book Rebellion caused the deaths of thousands of people from Devon and Cornwall. The Methodism of John Wesley proved to be very popular with the working classes in Cornwall in the 19th century. Methodist chapels became important social centres, with male voice choirs and other church-affiliated groups playing a central role in the social lives of working class Cornishmen. Methodism still plays a large part in the religious life of Cornwall today, although Cornwall has shared in the post-World War II decline in British religious feeling. In 1876 a separate Cornish diocese of the Church of England was established with the bishop's see at Truro.

Early history and legend

Nothing is known about the beginnings of Christianity in Cornwall. Scilly has been identified as the place of exile of two heretical 4th-century bishops from Gaul, Instantius and Tiberianus, who were followers of Priscillian and were banished after the Council of Bordeaux in 384.[3] Toleration was granted to the Christians of the Roman Empire in 313 and there was some growth in the church in Roman Britain in the following hundred years, mainly in urban centres. There were no known cities (L castrum, OE caester, W caer, Br Ker ) west of Exeter so Cornwall may have remained pagan at least until the 5th century, the presumed period of the mythical Christian King of the Britons, Arthur Pendragon. During the 5th century the earliest inscribed stones have inscriptions in Latin or Ogham script and some have Christian symbols. Precise dating is impossible for these stones but they are thought to come from the 5th to 11th centuries. Both the inscriptions and the Ruin of Britain by Gildas suggest that the leading families of Dumnonia were Christian in the 6th century.[4] Many early medieval settlements in the region were occupied by hermitage chapels which are often dedicated to St Michael as the conventional slayer of pagan demons, as at St Michael's Mount.

Many place names in Cornwall are associated with Christian missionaries described as coming from Ireland and Wales in the 5th century AD and usually called saints (See List of Cornish saints). The historicity of some of these missionaries is problematic[5] and it has been pointed out by Canon Doble that it was customary in the Middle Ages to ascribe such geographic origins to saints.[6] Some of these saints are not included in the early lists of saints.[7]

The Saints' Way, a long-distance footpath, follows the probable route of early Christian travellers making their way from Ireland to the Continent. Rather than risk the difficult passage around Land's End they would disembark their ships on the North Cornish coast (in the Camel estuary) and progress to ports such as Fowey on foot.

Like some other parts of Britain Cornwall derived much of its Christianity from post-Patrician Irish missions. Saint Ia of Cornwall and her companions, and Saint Piran, Saint Sennen, Saint Petroc, and the rest of the saints who came to Cornwall in the late 5th century and early 6th century found there a population which had perhaps relapsed into paganism under the pagan King Teudar.[8] When these saints introduced, or reintroduced, Christianity, they probably brought with them whatever rites they were accustomed to, and Cornwall certainly had its own separate ecclesiastical quarrel with Wessex in the days of Saint Aldhelm, which, as appears by a statement in the Leofric Missal, was still going on in the early 10th century, though the details of it are not specified.

It is notable that in Cornwall that most of the parish churches in existence in Norman times were generally not in the larger settlements and that the medieval towns which developed thereafter usually had only a chapel of ease with the right of burial remaining at the ancient parish church.[9] Over a hundred holy wells exist in Cornwall, each associated with a particular saint, though not always the same one as the dedication of the church.[10][11] In the Domesday Survey the church had considerable holdings of land but the Earl of Cornwall had appropriated a number of manors formerly held by monasteries. The monasteries of St Michael's Mount, Bodmin, and Tavistock, and the canons of St Piran, St Keverne, Probus, Crantock, St Buryan and St Stephen's all had land at this time.[12]

Various kinds of religious houses existed in medieval Cornwall though none of them were nunneries; the benefices of the parishes were in many cases appropriated to religious houses within Cornwall or elsewhere in England or France.[13] There were also a number of peculiars, areas outside the diocesan administration. Four of these were directly under the Bishop of Exeter, i.e. Lawhitton, St Germans, Pawton, and Penryn; Perranzabuloe was a peculiar of Exeter Cathedral and St Buryan of the Kings of England.[14] From the time of Bishop William Warelwast the administration of the remainder of Cornwall was in the hands of the Archdeacon of Cornwall and visits by the Bishop became more infrequent; only bishops could consecrate churches or conduct confirmations.

Patron saint

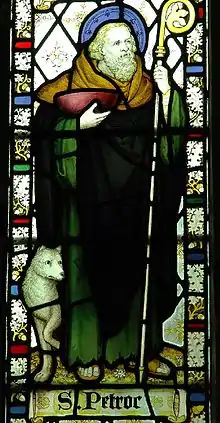

St Piran, after whom Perranporth is named, is generally regarded as the patron saint of Tinners and for some also of Cornwall.[15] However, in earlier times it is likely that St Michael the Archangel was recognised as the patron saint;[16] he is still recognised by the Church of England as the Protector of Cornwall.[17] (The cult of St Michael is found in Norman times and is seen in the naming of St Michael's Mount after the similarly named monastery in Normandy.) The title has also been claimed for Saint Petroc who was patron of the Cornish diocese prior to the Normans.[18]

Dioceses of Cornwall and Exeter

The church in Cornwall until the time of Athelstan of Wessex observed more or less orthodox practices, being completely separate from the Anglo-Saxon church until then (and perhaps later). The See of Cornwall continued until much later: Bishop Conan apparently in place previously, but (re-?)consecrated in 931 AD by Athelstan. However, it is unclear whether he was the sole Bishop for Cornwall or the leading Bishop in the area. The situation in Cornwall may have been somewhat similar to Wales where each major religious house equated to a kevrang (cf. Welsh cantref), each under the control of a bishop.[19]

According to Nicholas Orme "... a period of obscurity ... ends only after Egbert's conquest in the early 800s. Later records claim that he used his power to grant estates in Cornwall to the bishop of Sherborne, especially Pawton in St Breock and Lawhitton near Launceston. Egbert may have intended that the bishop would visit Cornwall or send deputies there to supervise or develop the local church."[20] By the 880s the Church in Cornwall was having more Saxon priests appointed to it and they controlled some church estates like Polltun, Caellwic and Landwithan (Pawton, in St Breock; perhaps Celliwig {Kellywick in Egloshayle?}; and Lawhitton). Eventually they passed these over to Wessex kings. However, according to Alfred the Great's will the amount of land he owned in Cornwall was very small.[21] West of the Tamar Alfred the Great only owned a small area in the Stratton region, plus a few other small estates around Lifton on Cornish soil east of the Tamar). These were provided to him illicitly through the Church whose Canterbury-appointed priesthood was increasingly English dominated.

William of Malmesbury, writing around 1120, says that King Athelstan of England (924–939) fixed Cornwall's eastern boundary at the east bank of the Tamar and the remaining Cornish were evicted from Exeter and perhaps the rest of Devon: "Exeter was cleansed of its defilement by wiping out that filthy race".[22] These British speakers were deported across the Tamar, which was fixed as the border of the Cornish; they were left under their own dynasty to regulate themselves with west Welsh tribal law and customs, rather like the Indian princes under the Raj in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[23] By 944 Athelstan's successor, Edmund I of England, styled himself 'King of the English and ruler of this province of the Britons',[24] an indication of how that accommodation was understood at the time.

The early organisation and affiliations of the Church in Cornwall are unclear, but in the mid-9th century it was led by a Bishop Kenstec with his see at Dinurrin, a location which has sometimes been identified as Bodmin and sometimes as Gerrans. Kenstec acknowledged the authority of Ceolnoth, bringing Cornwall under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the 920s or 930s King Athelstan established a bishopric at St Germans to cover the whole of Cornwall, which seems to have been initially subordinated to the see of Sherborne but emerged as a full bishopric (with a Bishop of Cornwall) in its own right by the end of the 10th century. The first few bishops here were native Cornish, but those appointed from 963 onwards were all English. From around 1027 the see was held jointly with that of Crediton, and in 1050 they were merged to become the diocese of Exeter.[25]

Three original records relating to the Cornish church which predate the Norman Conquest are the Bodmin Gospels; the Lanalet pontifical (associated with St Germans); and the Codex Oxoniensis Posterior, an anthology which includes a commentary on the mass and two works by Augustine of Hippo and Caesarius of Arles.[26]

The whole of Cornwall was from the Norman period onwards in the Archdeaconry of Cornwall within the Diocese of Exeter. From 1267 the archdeacons had a house at Glasney near Penryn. Their duties were to visit and inspect each parish annually, to execute the bishop's orders, and to induct (install) new parochial clergy. The archdeacon also held a court to deal with minor offences against ecclesiastical law and administer wills.[27] The first recorded archdeacon may have been Hugo de Auco (1130s).

In the late medieval period there were various ways for Cornishmen to acquire the education needed for ordination. Most of this education was in their own districts, e.g. at a school or monastery, but a few were able to spend many years studying at the University of Oxford. This was made easier by the founding there by Bishop Stapledon of Stapledon Hall and its successor Exeter College which drew students from the whole of the Westcountry. These Oxford students came both from the Cornish-speaking west of Cornwall and from the English-speaking east. The wealthiest families would be able to send some of their sons to Oxford and some others could obtain benefices first and then pay for their education from their income (the bishop would grant them leave of absence to attend the university). Some when they completed their studies came back to serve as parish clergy, but a few rose to be officers of universities or bishops or court officials.[28]

In the late medieval period there were as well as the parish clergy various monasteries and two friaries (at Bodmin and Truro). Since the population at that time included those who only spoke Cornish and those who spoke both Cornish and English and as well as those who only knew English Bishop Grandisson appointed three bilingual friars to minister to Cornish speakers. The friaries were centres of learning and the friars were criticised by some for associating themselves with the rich rather than the poor.[29]

The parochial system was complex consisting as it did of a mixture of parishes, chapelries and peculiar jurisdictions (e.g. St Buryan). The parish of St Minver had chapelries of Porthilly and St Enodoc; Probus had chapelries of Cornelly and Merther and there were others. St Ives was a chapelry of Lelant before it was granted parochial status (until 1902 Towednack was also a chapelry of Lelant). Though St Agnes had a majority of the population it remained a chapelry of Perranzabuloe until 1846. South Petherwin had chapelries of Trewen and Launceston (St Mary Magdalene). [30][31]

Liturgy

There is a Mass in Bodl. MS. 572 (at Oxford), in honour of St Germanus, which appears to be Cornish and relates to "Ecclesia Lanaledensis", which has been considered to be the monastery of St. Germanus, in Cornwall. There is no other evidence of the name, which was also the Breton name of Aleth, now part of Saint-Malo. The manuscript, which contains also certain glosses, possibly Cornish or Breton—it would be impossible to distinguish between them at that date—but held by Professor Loth to be Welsh, is probably of the 9th century, and the Mass is quite Roman in type, being probably written after that part of Cornwall had come under Saxon influence. There is a very interesting Proper Preface.![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

Joseph of Arimathea

Ding Dong mine, reputedly one of the oldest in Cornwall, in the parish of Gulval is said in local legend to have been visited by Joseph of Arimathea, a tin trader, and that he brought a young Jesus to address the miners, although there is no evidence to support this.[32]

Religious history from the Reformation to the early 21st century

16th and 17th centuries

Tudor period, 1509–1603

The failure to translate the first Prayer Book into the Cornish language and the imposition of English liturgy over the Latin rite in the whole of Cornwall contributed to the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549.[33][34] There had already been dissent in Cornwall from the changes in the church enacted by the government of Edward VI abolishing chantries and reforming some aspects of the liturgy.[35] The Cornish, amongst other reasons, objected to the English language Book of Common Prayer, protesting that the English language was still unknown to many at the time. Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset on behalf of the Crown, expressed no sympathy, pointing out that the old rites and prayers had been in Latin—also a foreign language—and there was thus no reason for the Cornish to complain. The Prayer Book Rebellion was a cultural and social disaster for Cornwall, and the reprisals taken by the forces of the Crown have been estimated to account for 10–11% of the civilian population of Cornwall. Culturally speaking, it saw the beginning of the slow "death" of the Cornish language.

Penal laws against Roman Catholics were enacted by the English government in 1571 and 1581. By this time people of papal sympathies had diminished in number but they included the two powerful families of Arundell and Tregian. A priest (Cuthbert Mayne) harboured by the Tregians was arrested and eventually executed at Launceston in 1577. Francis Tregian was punished by imprisonment and the loss of some of his lands. Others who were adherents of the old faith went into exile, including the rectors of St Michael Penkevil and St Just in Roseland, Thomas Bluett and John Vivian respectively. Among laymen the most notable was Nicholas Roscarrock, who was imprisoned and compiled while in prison a register of British saints.[36]

From that time Christianity in Cornwall was in the main within the Church of England and subject to the national events which affected it in the next century and a half. Roman Catholicism never became extinct, though it was openly practised by very few. Also at this period there was an increase in adherents of the Puritan position as evidenced by the acquisition of large communion cups in many parishes in the 1570s.

Stuart period, 1603–1714

In the reign of Charles I, the leading gentry of the Puritan party were the Robarteses of Lanhydrock, the Bullers of Morval, the Boscawens of Tregothnan and the Rouses of Halton, while Puritan clergy were to be found at Blisland, Morval, Landrake, and Mylor. However, during the Civil War there was much more support in Cornwall for the Anglican and Royalist position and the military successes of the Royalist army delayed any imposition of Presbyteriansim in church administration. The Parliamentary success in 1645 led to the ejection of the Bishop of Exeter and the depriving of the cathedral chapter. In 1646 the 72 clergy regarded as unacceptable to the county committee were required to subscribe to the new order. Some submitted while others were obstinate and so were deprived of their benefices. Civil marriage was instituted in 1653 but was not popular; much iconoclasm took place in churches such as the destruction of the stained glass at St Agnes and the rood screen at St Ives. The church organs at Launceston and St Ives were also destroyed.[37]

During the 17th century, adherents of Roman Catholicism tended to diminish since only a few could afford the penalties exacted by the government. Lanherne, the Cornish home of the Arundells in Mawgan in Pydar, was the most important centre, while the religious census of 1671 recorded recusants also in the parishes of Treneglos, Cardinham, Newlyn East and St Ervan. In the Civil War, the recusants were firmly of Royalist sympathies since they had more to fear from a Parliament opposed to prelacy and popery. Sir John Arundell (born ca. 1625) fought gallantly for King Charles in the Cornish campaign, which he joined in 1644, and continued to live at Lanherne until his death in 1701.[38]

At the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, ministers unwilling to conform to the Church of England were ejected from the benefices. Under the Conventicle Act 1664 non-Anglican services were only permitted in private houses and only with five persons attending apart from the household. In Cornwall, there were about 50 ejected ministers, some of whom persisted in conducting meetings in out of the way places: these included Thomas Tregosse, formerly vicar of Mylor and Mabe, Joseph Sherwood of Penzance, and Henry Flamank of Lanivet.[39]

A number of prominent men holding Baptist views were to be found in Cornwall in the 1650s, such as John Pendarves, John Carew and Hugh Courtney. At the restoration of the monarchy such people became dissenters and they were only found in a few settlements such as Falmouth and Looe.[40]

George Fox, the founder of the Quakers, visited Cornwall in 1655 and found followers in Loveday Hambly, of Tregongeeves near St Austell, and Thomas Mounce, of Liskeard. The early Cornish Quakers endured much persecution but after 1675 they made many converts. Once the opening of meeting houses became legal in 1689 their position became much easier and by 1700 there were altogether 27 societies with about 400 adherents.[41]

The last church services conducted in Cornish were in the far west (Penwith) in the late 17th century: Towednack is recorded as the place (in 1678) and the claim is also made for Ludgvan.

1714–1800

The few Roman Catholics, Baptists and Quakers were now largely free of persecution. During the remainder of the 18th century, Cornish Anglicanism was very much in the same state as Anglicanism in most of England. Wesleyan Methodist missions began during John Wesley's lifetime and had great success over a long period during which Methodism itself divided into a number of sects and established a definite separation from the Church of England.

After the death of Queen Anne there was some support in Cornwall for the Jacobite cause, e.g. at St Columb. In the first half of the 18th century some more substantial parsonage houses were built in Cornwall, e.g. at Linkinhorne and St Gennys. Two charitable funds were established at this time, one to help clergymen's widows and orphans, the other to help necessitous clergymen. Books and pamphlets published by the newly founded S.P.G. and S.P.C.K. were distributed in some parishes by the clergy, e.g. at St Gluvias.[42] An ascendancy of Whig and Latitudinarian principles came in with the Georgian era. The times were characterized by controversies with the Deists and the official church adopted a position more consonant with appeals to reason and the natural order. However, an official church preoccupied with great minds and leading families was ill-equipped to retain the loyalty of illiterate miners and labourers such as formed most of the population of Cornwall. Local law and administration were in the hands of the vestry and churchwardens; but the clergy's interests were remote from the cares of the lowly.[43] In this period there was an expansion of mining which often resulted in shifts of population away from the old parish churches. Beginning in 1744 there was a series of questionnaires sent by the bishops in advance of their visitations; the replies to these show that two services were commonly celebrated on Sundays and in some churches there were also services on some weekdays. In the towns holy communion was celebrated monthly but in country parishes perhaps only three or four times a year. The replies indicate a downward trend in church attendance between 1744 and 1821; e.g. at Padstow church attendance was normally 100, but in 1779 only 80, and in 1821 fewer still at 60–70. The replies for 1744 also show that many incumbents were non-resident: 110 were resident but 36 were not. The replies for 1779 show that non-residence had increased: 89 were now resident and 57 were non-resident.[44] For example at Tintagel three successive vicars from 1726 to 1770 were non-resident.[45]

In 1743 Charles and John Wesley came to Cornwall as evangelists (Charles arrived three weeks earlier than John); they aimed their mission at the population of the newly industrialised areas. Their meetings were held at times different from the usual church services which their hearers were encouraged to attend also. Their converts were formed into local societies led by class leaders and exhorters recruited locally. The timing of the mission was unfortunate as it coincided with an expectation of invasion by the French; the formation of the Methodist societies was understood by some as a preparation for the invasion of the country. John Wesley's Journal for 1743, 1744 and 1745 records several incidents of mob violence directed at Methodist meeting places and in 1745 John Wesley was himself threatened by a mob at Falmouth.[46]

By 1747 the threat of an invasion in support of the Young Pretender was over and there was no more opposition to Methodist preaching. In the second half of the 18th century the expansion of mining was added by steam power; Methodism attracted many adherents among the miners, particularly in the period after 1780. However the growth of Methodism was not steady; there was a pattern of revivals at intervals of about 16 years; these were in 1764, 1782. 1799 and 1814 (known as the "great revival". The earliest Methodist meeting houses were not licensed as meeting places of Dissenters as Methodists still maintained their membership of the Church of England though this policy was changed in 1785. Samuel Walker of Truro was the most prominent member of a group of clergy whose interpretation of religion was evangelical. Samuel Walker taught his parishioners the Gospel and upheld the teaching of the Church, having formed them into societies somewhat similar to those of the Methodists. Samuel, James and Robert Walker (of Truro, St Agnes and Lawhitton; John Penrose (St Gluvias), St John Elliot (Ladock), Michel of Veryan and Thomas of St Clement formed themselves into a "Clerical Club" which met monthly from 1750. These clergy differed from the Wesleys in that their theology was Calvinistic rather than Arminian. Other evangelical clergy were Samuel Furly, sen., rector of Roche (1766–95); Thomas Biddulph, vicar of Padstow (1771–90); and William Rawlings of Padstow (1790–1836).[47]

Later Methodists came to regard their own system as a complete expression of the Christian religion. Some parish clergy were hostile to attenders at Methodist meetings while others merely ill-disposed. Methodism was the religion of the poor and later that of the new middle class. Methodists began to find the link with the parish church uncongenial; after 1786 Wesley permitted the holding of Methodist services at the same time as those in the parish church where the incumbents were Calvinists or hostile to Methodism. One of the attractions of Methodist meetings was the singing of hymns. In the middle of the 18th century there was a renewed interest in singing in parish churches and village bands make their appearance. There was also a revival of bell ringing. Until this time most churches had only three bells. In the 18th century many churches added to the number of bells and the practice of ringing in peals became common. Between 1712 and 1824, 83 peals were cast for Cornish churches. Many of the bells were cast by the Penningtons of Bodmin and Stoke Climsland, some by the Rudhalls of Gloucester and a few by other founders. Another effect of Methodism was to instigate attempts to increase the accommodation in the parish churches, as in the rebuildings of the churches of Helston (1761) and Redruth (1768). Another reaction to Methodism among some clergy was the revivification of the old High Church theology. The doctrines of justification, assurance and the sacraments were studied and taught and there was a new valuation of the priestly mission. John Whitaker of Ruan Lanihorne was one example of these high churchmen; he was the author of The Ancient Cathedral of Cornwall (1804).[48]

19th and 20th centuries

From the early 19th to the mid-20th century Methodism was the leading form of Christianity in Cornwall but is now (early 21st century) in decline.[49][50] The Church of England was in the majority from the reign of Queen Elizabeth I until the Methodist revival of the 19th century: before the Wesleyan missions dissenters were very few in Cornwall. The Quaker family, the Foxes of Falmouth, had many notable members involved in philanthropy and cultural life.[51]

The episcopate of Henry Phillpotts (1830–1869) was a period of great Anglican activity with the establishment of many new parishes and parish churches and the first unsuccessful attempts to recreate a Cornish diocese. This was proposed in the mid 1840s when the need for new dioceses in England was recognised but only the new Manchester diocese was actually founded. Over the next thirty years various further proposals were made, beginning with one for a bishop of Cornwall with his seat at Bodmin. However Bodmin's central position, status as the county town and place in history were not enough to overcome opposition. Samuel Walker of St Columb Major proposed to contribute part of his rich benefice towards the new see but this later became impossible (and the town was of minor importance in the county). Arguments in favour of a new diocese were reinforced by the size of the then Diocese of Exeter (population 900,000, of which 400,000 were in Cornwall; Wales then had four bishops for a slightly larger population). In Cornwall, the west had a greater density of population which suggested that the commercial town of Truro was the best place for the new see. It also had a good provision of parish churches, unlike Bodmin with its single large and ancient church.[52]

The county remained within the Diocese of Exeter until 1876 when the Anglican Diocese of Truro was created[53][54] (the first Bishop was appointed in 1877). Roman Catholicism was virtually extinct in Cornwall after the 17th century except for a few families such as the Arundells of Lanherne. From the mid-19th century, the church reestablished episcopal sees in England, one of these being at Plymouth.[55] Since then immigration to Cornwall has brought more Roman Catholics into the population. Religious houses have been established at several locations including Bodmin, and Roman Catholic churches have been built where the need for them is apparent.

Other significant trends during the 20th century were the spread of Anglo-Catholicism in Church of England parishes and the movement towards unification of the Anglican and Methodist Churches in the 1960s. As the bishops were sometimes High Church (e.g. W. H. Frere) and sometimes Low (e.g. Joseph Hunkin) administration of the diocese could vary from each episcopate to the next. The usage of Cornish as a liturgical language has become much more common.

The Cornish diaspora has contributed to the international spread of Methodism, a movement within Protestant Christianity that was popular with the Cornish people at the time of their mass migration.[56]

Recent developments

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries there has been a renewed interest in the older forms of Christianity in Cornwall. Cowethas Peran Sans, the Fellowship of St Piran, was one such group (now dissolved) promoting practices associated with Celtic Christianity.[57] The group was founded by Andrew Phillips in 2006 and membership was open to baptised Christians in good standing in their local community who support the aims of the group.

In 2003, a campaign group was formed called Fry an Spyrys (Free the Spirit in Cornish).[58] It is dedicated to disestablishing the Church of England in Cornwall and to forming an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion – a Church of Cornwall. Its chairman is Dr Garry Tregidga of the Institute of Cornish Studies. The Anglican Church was disestablished in Wales to form the Church in Wales in 1920 and in Ireland to form the Church of Ireland in 1872.

In recent decades Methodism in particular has declined numerically. There has been substantial growth in the evangelical/charismatic church sector, with numerous new churches planted. Many of these meet in schools or halls, so are not always obviously visible, but they bring much energy into the church and demonstrate that there is growth as well as decline.

Medieval and early modern religious literature

Works in verse

Pascon agan Arluth (The Passion of our Lord), a poem of 259 eight-line verses probably composed around 1375, is one of the earliest surviving works of Cornish literature.[59] The most important work of literature surviving from the Middle Cornish period is the Cornish Ordinalia, a 9000-line religious verse drama which had probably reached its present form by 1400. The Ordinalia consists of three miracle plays, Origo Mundi, Passio Christi and Resurrexio Domini, meant to be performed on successive days. Such plays were performed in a 'Plain an Gwarry' (i.e. Playing Place).[60]

The longest single surviving work of Cornish literature is Beunans Meriasek (The Life of Meriasek), a two-day verse drama dated 1504, but probably copied from an earlier manuscript. (This has been studied since the 1890s whereas the only other known Cornish drama portraying events in a saint's legend, Beunans Ke, was only found in the early years of the 21st century.)

Other notable pieces of Cornish literature include the Creation of the World (with Noah's Flood) which is a miracle play similar to Origo Mundi but in a much later manuscript (1611); the Charter Fragment, a short poem about marriage, believed to be the earliest connected text in the language; and the recently discovered Beunans Ke, another saint's play, notable for containing a long Arthurian section.

Works in prose

The earliest surviving examples of Cornish prose are the Tregear Homilies, a series of 12 Catholic sermons written in English and translated by John Tregear around 1555–1557, to which a thirteenth homily The Sacrament of the Alter [sic], was added by another hand. Twelve of Edmund Bonner's Homelies to be read within his diocese of London of all Parsons, vycars and curates (1555; nine of these were by John Harpsfield) were translated into Cornish by Tregear; they are the largest single work of traditional Cornish prose.

Church architecture and monuments

Stone crosses

_(14777375892).jpg.webp)

Wayside crosses and Celtic inscribed stones are found in Cornwall in large numbers; the inscribed stones (about 40 in number) are thought to be earlier in date than the crosses and are a product of Celtic Christian society. It is likely that the crosses represent a development from the inscribed stones but nothing is certain about the dating of them. In the late Middle Ages it is likely that their erection was very common. Since they occur in locations of various types, e.g. by the wayside, in churchyards, and in moorlands. Those by roadsides and on moorlands were doubtless intended as rout markings. A few may have served as boundary stones, and others like the wayside shrines found in Catholic European countries. Crosses to which inscriptions have been added must have been memorial stones. According to W. G. V. Balchin "The crosses are either plain or ornamented, invariably carved in granite, and the great majority are of the wheel-headed Celtic type." Their distribution shows a greater concentration in west Cornwall and a gradual diminution further east and further north. In the extreme northeast none are found because it had been settled by West Saxons. The cross in Perran Sands has been dated by Charles Henderson as before 960 AD; that in Morrab Gardens, Penzance, has been dated by R. A. S. Macalister as before 924 AD; and the Doniert Stone is thought to be a memorial to King Dumgarth (died 878).[61]

Celtic art is found in Cornwall, often in the form of stone crosses of various types. Cornwall boasts the highest density of traditional 'Celtic crosses' of any nation (some 400). Charles Henderson reported in 1930 that there were 390 ancient crosses and in the next forty years, a number of others have come to light.[62] In the 1890s Arthur G. Langdon collected as much information as he could about these crosses (Old Cornish Crosses; Joseph Pollard, Truro, 1896) and one hundred years later Andrew G. Langdon has done a survey in the form of five volumes of Stone Crosses in Cornwall, each volume covering a region (e.g. Mid Cornwall) which the Federation of Old Cornwall Societies has published.[63]

In modern times many crosses were erected as war memorials and to celebrate events such as the millennium. "Here is an example of continuity in cultural traits extending over many generations: for we can look beyond the medieval cross to the inscribed stone and even farther back to the prehistoric mênhir, and yet bring the custom right up-to-date with the twentieth-century war memorial."—W. G. V. Balchin (1954).[64]

Church architecture

The church architecture of Cornwall and Devon typically differs from that of the rest of southern England: most medieval churches in the larger parishes were rebuilt in the later medieval period with one or two aisles and a western tower, the aisles being the same width as the nave and the piers of the arcades being of one of a few standard types. Wagon roofs often survive in these churches. The typical tower is of three stages, often with buttresses set back from the angles.[65] Only a few Cornish church towers are beautiful or striking, the majority are plain and dull. Part of the reason is the shortage of good building stone in the county.[66] The arcades of those churches with aisles generally have piers of one of three different types: Type A "consists of four attached shafts in the main axes and four hollows in the diagonals"; Type B which seems to have been in use earlier has "square piers with four attached demi-shafts"; or octagonal piers. Type A is very common in both Devon and Cornwall.[67]

Churches of the Decorated period are relatively rare, as are those with spires; about a dozen churches have spires, the most elaborate being at Lostwithiel.[68] There are very few churches from the 17th and 18th centuries. There is a distinctive type of Norman font in many Cornish churches which is sometimes called the Altarnun type. The style of carving in bench ends is also recognisably Cornish.[69]

Church plate

Nearly 100 pieces of communion plate in Cornish churches were made in the Elizabethan period, that is, between the years 1570 and 1577. Only one piece of pre-Reformation plate survives, an unremarkable paten at Morval dated 1528–29. Most of the Elizabethan pieces were made by Westcountry goldsmiths who include John Jons of Exeter (about 25). There are 47 pieces of communion plate from the Stuart period (up to 1685). 22 examples of flagons for the wine made in the 17th century still exist, and there are two at Minster dated 1588. At Kea is a French chalice and paten (1514 or 1537) donated by Susannah Haweis and at Antony three foreign chalices, two of these are Sienese of the 14th century and one is Flemish and dated 1582.[70]

Religious houses

East Cornwall

Saint Petroc founded monasteries at Padstow and Bodmin: Padstow, which is named after him (Pedroc-stowe, or 'Petrock's Place'), appears to have been his base for some time before he moved to Bodmin. The monastery suffered raids from Viking pirates and the monks moved to Bodmin.

The Bodmin monastery was deprived of some of its lands at the Norman Conquest but in the late 11th century, at the time of Domesday Book, it still held 18 manors including Bodmin, Padstow and Rialton.[71][72] In the 15th century the Norman Church of St Petroc was largely rebuilt and stands as one of the largest churches in Cornwall (the largest after the cathedral at Truro).

Also at Bodmin are remains from the substantial Franciscan Friary established ca. 1240: a gateway in Fore Street and two pillars elsewhere in the town. The Roman Catholic Abbey of St Mary and St Petroc was built in 1965 next to the already existing seminary.[73]

St German's Priory was built over a Saxon building which was the cathedral of the Bishops of Cornwall. The monastery was reorganised by the Bishop of Exeter between 1161 and 1184 as an Augustinian priory and the new church was built on a grand scale, with two western towers and a nave of 102 ft.

At St Stephens by Launceston the parish church, dedicated to St Stephen, is on the northern outskirts of the town of Launceston. The church was built in the early 13th century after Launceston Priory moved from this site into the valley near the castle. (The name of Launceston belonged originally to the monastery and town here, but was transferred to the town of Dunheved.)

It was formerly believed that a monastery existed on the site of Tintagel Castle but modern discoveries have refuted this. There was, however, a pre-Conquest monastery at Minster near Boscastle.

At St Endellion the church is a rare example of a collegiate church not abolished at the Reformation.

West Cornwall and Scilly

At St Buryan King Athelstan endowed the building of collegiate buildings and the establishment of one of the earliest monasteries in Cornwall, and this was subsequently enlarged and rededicated to the saint in 1238 by Bishop William Briwere. The collegiate establishment consisted of a dean and three prebendaries.[74][75][76][77][78]

Glasney College was founded at Penryn, Cornwall in 1265 by Bishop Bronescombe and was the centre of ecclesiastical power in Cornwall's Middle Ages and probably the best known and most important of Cornwall's monastic institutions. Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries, between 1536 and 1545, signalled the end of the big Cornish priories but as a chantry church, Glasney held on until 1548 when it suffered the same fate. The smashing and looting of Cornish colleges such as Glasney and Crantock brought an end to the formal scholarship that had helped sustain the Cornish language and Cornish cultural identity.

_and_its_history_-_geograph.org.uk_-_894668.jpg.webp)

At St Mawgan Lanherne House, mainly built in the 16th and 17th centuries, became a convent for Roman Catholic nuns from Belgium in 1794.

St Michael's Mount may have been the site of a monastery from the 8th to early 11th centuries and Edward the Confessor gave it to the Norman abbey of Mont Saint-Michel.[79] It was a priory of that abbey until the dissolution of the alien houses by Henry V, when it was given to the abbess and Convent of Syon at Isleworth, Middlesex. It was a resort of pilgrims, whose devotions were encouraged by an indulgence granted by Pope Gregory in the 11th century. The monastic buildings were built during the 12th century but in 1425 as an alien monastery it was suppressed.[79]

During Anglo-Saxon times the oratory site in Perranzabuloe was the site of an important monastery known as Lanpiran or Lamberran. It was disendowed ca. 1085 by Robert of Mortain. The later church preserved the relics of St Piran and was a major centre of pilgrimage: the relics are recorded in an inventory made in 1281 and were still venerated in the reign of Queen Mary I according to Nicholas Roscarrock's account. It is believed that Saint Piran founded the church near to Perranporth (the "Lost Church") in the 7th century.

In early times the Isles of Scilly were in the possession of a confederacy of hermits. King Henry I gave the hermits' territory to the abbey of Tavistock, which established a priory on Tresco that was abolished at the Reformation.[80] Tresco Priory[81] was founded in 946 AD.

In Truro, Bishop Wilkinson founded a community of nuns, the Community of the Epiphany.[82] George Wilkinson was afterwards Bishop of St Andrews.[83] The sisters were involved in pastoral and educational work and the care of the cathedral.[84]

Biblical translations

There have also been Bible translations into Cornish. This redresses a perceived handicap unique to Cornish, in that of all the Celtic languages, it was only Cornish that did not have its own translation of the Bible.

- The first complete edition of the New Testament in Cornish, Nicholas Williams's translation of the Testament Noweth agan Arluth ha Savyour Jesu Cryst, was published at Easter 2002 by Spyrys a Gernow (ISBN 0-9535975-4-7); it uses Unified Cornish Revised orthography. The translation was made from the Greek text, and incorporated John Tregear's existing translations with slight revisions.

- In August 2004, Kesva an Taves Kernewek published its edition of the New Testament in Cornish (ISBN 1-902917-33-2), translated by Keith Syed and Ray Edwards; it uses Kernewek Kemmyn orthography. It was launched in a ceremony in Truro Cathedral attended by the Archbishop of Canterbury. A translation of the Old Testament is currently under preparation.

- The first complete translation of the Bible into Cornish, An Beybel Sans, was published in 2011 by Evertype. It was translated by Nicholas Williams, taking a total of 13 years to complete.[85][86]

Theological library

The Bishop Phillpotts Library in Truro, Cornwall, founded by Bishop Henry Phillpotts in 1856 for the benefit of the clergy of Cornwall, continues to be an important centre for theological and religious studies, with its more than 10,000 volumes, mainly theological, open to access by clergy and students of all denominations. It was opened in 1871 and almost doubled in size in 1872 by the bequest of the collection of Prebendary Ford (James Ford, Prebendary of Exeter).[87]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Bowen, E. G. (1977) Saints, Seaways and Settlements in the Celtic Lands. Cardiff: University of Wales Press ISBN 0-900768-30-4

- ↑ Wall, J. Charles (1912) Porches & Fonts London: Wells Gardner & Darton; p. 180

- ↑ "Priscillianus and Priscillianism". Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of Sixth Century. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ↑ Orme, Nicholas (2007) Cornwall and the Cross. Chichester: Phillimore; pp. 4–5

- ↑ Orme, Nicholas (2000) The Saints of Cornwall, see also Article on "Saint Uny" at http://www.lelant.info/uny.htm. The patron saint of Wendron Parish Church, "Saint Wendrona", is another example.

- ↑ Doble, G. H. (1960) The Saints of Cornwall. 5 vols. Truro: Dean and Chapter, 1960–70

- ↑ see for example absences from Olsen and Padel's "A tenth century list of Cornish parochial saints" in Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies; 12 (1986); and from Nova Legenda Angliae by John Capgrave (mid-15th century)

- ↑ King Teudar appears as a tyrant in the early 16th-century plays Beunans Ke and Beunans Meriasek, in which he comes into conflict with Saint Kea and Saint Meriasek, respectively.

- ↑ Cornish Church Guide (1925) Truro: Blackford

- ↑ Jenner, Henry (1925) "The Holy Wells of Cornwall", in: Cornish Church Guide. Truro: Blackford; pp. 249–257

- ↑ Quiller-Couch, Mabel and Lilian (1894) Ancient and Holy Wells of Cornwall. London : Chas. J. Clark

- ↑ Thorn, Caroline & Frank (eds.) (1979) Domesday Book. 10: Cornwall. Chichester: Phillimore

- ↑ Oliver, George(1846) Monasticon Dioecesis Exoniensis: being a collection of records and instruments illustrating the ancient conventual, collegiate, and eleemosynary foundations, in the Counties of Cornwall and Devon, with historical notices, and a supplement, comprising a list of the dedications of churches in the Diocese, an amended edition of the taxation of Pope Nicholas, and an abstract of the Chantry Rolls [with supplement and index]. Exeter: P. A. Hannaford, 1846, 1854, 1889

- ↑ Orme, N. (2007) Cornwall and the Cross. Chichester: Phillimore; pp. 28–29

- ↑ "St. Piran – Sen Piran". St-Piran.com. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Henderson, C. G. (1933) "Cornwall and her patron saint", In: his Essays in Cornish History. Oxford: Clarendon Press; pp. 197–201

- ↑ Wyatt, Tim (2 May 2014). "Cornish welcome new status". Church Times. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ The cult of St Petroc was the most important in the Diocese of Cornwall since he was the founder of the monastery of Bodmin the most important in the diocese and, with St Germans, the seat of the bishops. He was the patron of the diocese and of Bodmin: Caroline Brett, "Petroc (fl. 6th cent.)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 16 December 2008

- ↑ Charles-Edwards, T. (1970–1972), "The Seven Bishop Houses of Dyfed", In: Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies, vol. 24, (1970–1972), pp. 247–252.

- ↑ Orme, Nicholas (2007) Cornwall and the Cross: Christianity, 500–1560. Chichester: Phillimore in association with the Institute of Historical Research at the University of London ISBN 1-86077-468-7; p. 8

- ↑ Keynes, Simon & Lapidge, Michael (tr.) (1983) Alfred the Great: Asser's "Life of King Alfred" and other contemporary sources. London: Penguin; p. 175; cf. ibid, p. 89.

- ↑ Payton Cornwall

- ↑ Wood, Michael (1986) Domesday: a Search for the Roots of England London: Guild Publishing; p. 188

- ↑ Todd, Malcolm (1987) The South West to AD 1000; p. 289

- ↑ Todd, Malcolm (1987) The South West to A.D. 1000. London: Longman, pp. 287–89

- ↑ Orme (2007), p. 20

- ↑ Orme, Nicholas (2007) Cornwall and the Cross: Christianity, 500–1560. Chichester: Phillimore; p. 29

- ↑ Orme, Nicholas (2007) Cornwall and the Cross. Chichester: Phillimore; pp. 82–86

- ↑ Orme, Nicholas (2007) Cornwall and the Cross. Chichester: Phillimore; pp. 74-75

- ↑ The Cornish Church Guide; parochial history, pp. 53 et seqq, (1925) Truro: Blackford

- ↑ Orme, Nicholas (2007) Cornwall and the Cross; Christianity 500-1560. Chichester: Phillimore; pp. 107-110

- ↑ Matthews, John (ed.) (1991) A Glastonbury Reader: Selections From the Myths, Legends and Stories of Ancient Avalon. London: HarperCollins (reissued by The Aquarian Press)

- ↑ Caraman, Philip (1994) The Western Rising 1549: the Prayer Book Rebellion. Tiverton: Westcountry Books ISBN 1-898386-03-X

- ↑ "The Prayer Book Rebellion 1549". TudorPlace.com.ar. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Orme, N. (2007) Cornwall and the Cross. Chichester: Phillimore; pp. 142–45

- ↑ Brown, H. Miles (1964) The Church in Cornwall. Truro: Blackford; pp. 78–83

- ↑ Brown, H. Miles (1964) The Church in Cornwall. Truro: Blackford; pp. 52–58

- ↑ He joined the King's forces at Boconnoc at the age of 19. Subsequently, the house was only occasionally inhabited and later came into the possession of the Arundells of Wardour. Brown, H. Miles (1964) The Church in Cornwall. Truro: Blackford; pp. 78–83

- ↑ Brown, H. Miles (1964) The Church in Cornwall. Truro: Blackford; pp. 83–85

- ↑ Brown, H. Miles (1964) The Church in Cornwall. Truro: Blackford; pp. 87–88

- ↑ Meeting houses from the early period are at Marazion (1688) and Come to Good(1710) still serve the Religious Society of Friends.

- ↑ Brown, H. Miles (1964) The Church in Cornwall. Truro: Blackford; p. 64

- ↑ Brown (1964); pp. 65–66

- ↑ Brown (1964); pp. 66–67

- ↑ Canner, A. C. (1982) The Parish of Tintagel. Camelford; pp. 50-51 & 55-56

- ↑ Brown (1964); pp. 68-69

- ↑ Brown (1964); pp. 70–72

- ↑ Brown (1964); pp. 74–76

- ↑ "Methodism". Cornish-Mining.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Shaw, Thomas (1967) A History of Cornish Methodism. Truro: Bradford Barton

- ↑ Brown, H. Miles (1964) The Church in Cornwall. Truro: Blackford; pp. 90–91

- ↑ Brown, H. Miles (1976) A Century for Cornwall. Truro: Blackford; pp. 10-21

- ↑ "Truro Cathedral website – History page". TruroCathedral.org.uk. Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Brown, H. Miles (1976) A Century for Cornwall. Truro: Blackford

- ↑ "Diocese of Plymouth". Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ↑ Hempton, David (2006). Methodism: Empire of the Spirit. Yale University Press. pp. 26–28. ISBN 978-0-300-11976-3.

- ↑ "Cowethas Peran Sans: Fellowship of St Piran". Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ "Fry an Spyrys". Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ Text and translation given at Early Cornish texts

- ↑ St Just Plain-an-Gwarry. Historic Cornwall. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ↑ Balchin (1954), pp. 62-63

- ↑ Hardy, Evelyn (1972, April/May) "Hardy's runic stone?", in: London Magazine; New series, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 85-91; citing Henderson's Cornwall: a Survey (1930), made for the Council for the Protection of Rural England

- ↑ 1: North Cornwall; 2: Mid Cornwall; 3: East Cornwall; 4: West Penwith; 5: West Cornwall. There are 2nd eds. of nos. 1, 2 and 3. N.B. The two Langdons are unrelated.

- ↑ Balchin, W. G. V. (1954) Cornwall: an illustrated essay on the history of the landscape. London: Hodder & Stoughton; p. 63

- ↑ Wheatley, Reginald F. (1925) "The architecture of the Cornish parish church" in: Cornish Church Guide. Truro: Blackford; pp. 225–234, 4 plates

- ↑ Hoskins, W. G. (1970) The Making of the English Landscape. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books; p. 129

- ↑ Pevsner, N. (1970) Cornwall; 2nd ed., revised by Enid Radcliffe. Harmondsworth: Penguin; pp. 18–19

- ↑ Pevsner (1970); p. 19

- ↑ Pevsner, Nikolaus (1970) Buildings of England: Cornwall; 2nd edition revised by Enid Radcliffe; Harmondsworth: Penguin ISBN 0-300-09589-9 ' pp. 18–20

- ↑ Mills, Canon (1925) "Cornish Church Plate" in: Cornish Church Guide. Truro: Blackford; pp. 235–40

- ↑ Thorn, C. et al. (eds.) (1979) Cornwall. Chichester: Phillimore; entries 4,3–4.22

- ↑ W. H. Pascoe's 1979 A Cornish Armory gives the arms of the priory and the monastery: Priory – Azure three salmon naiant in pale Argent – Monastery – Or on a chevron Azure between three lion's heads Purpure three annulets Or

- ↑ Pevsner, N. (1970) Cornwall, 2nd ed. Penguin Books.

- ↑ Stone, John Frederick Matthias Harris (1912) England's Riviera: a topographical and archæological description of Land's End, Cornwall and adjacent spots of beauty and interest. London: Kegan Paul Trench, Trübner & Co.

- ↑ Olson, Lynette (1989) Early Monasteries in Cornwall. Woodbridge: Boydell ISBN 0-85115-478-6

- ↑ "Domesday Book, folio 121b, chapter 4, paragraph 27".

- ↑ Wasley, K. (n.d.) ""St Buryan". Archived from the original on 3 May 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- ↑ The Cornish Church Guide (1925) Truro: Blackford; pp. 67–68

- 1 2 Pevsner, N. (1970) Cornwall; 2nd ed. Penguin Books; pp. 193–195

- ↑ The Cornish Church Guide; p. 194

- ↑ Historic England, "Remains of Tresco Priory and Associated Monuments and Attached Walls (1141172)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 3 October 2016

- ↑ Article by Richard Savill "Last surviving nun of 127-year-old order" (p. 7) The Daily Telegraph Tuesday 4 November 2008

- ↑ "Death of The Bishop of St. Andrews" The Times Thursday, 12 December 1907; p. 4; Issue 38514; col C

- ↑ Cornish Church Guide. Truro: Blackford; pp. 325–26

- ↑ "Holy Bible translated into Cornish". Press Association. 3 October 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ↑ The Holy Bible in Cornish

- ↑ Cornish Church Guide (1925) Truro: Blackford; p. 328

Further reading

Hagiography

- Baring-Gould, S.; Fisher, John (1907) Lives of the British Saints: the saints of Wales and Cornwall and such Irish saints as have dedications in Britain. 4 vols. London: For the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, by C. J. Clark, 1907–1913

- Borlase, W. C. (1895) The Age of Saints in Cornwall: early Christianity in Cornwall with legends of the Cornish saints. Truro: Joseph Pollard

- Bowen, E. G. (1954) The Settlements of the Celtic Saints in Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press

- Lewis, H. A. (ca. 1939) Christ in Cornwall?: legends of St. Just-in-Roseland and other parts. Falmouth: J. H. Lake

- Rees, W. J. (ed.) (1853) Lives of the Cambro British Saints: of the fifth and immediate succeeding centuries, from ancient Welsh & Latin mss. in the British Museum and elsewhere, with English translations and explanatory notes. Llandovery: W. Rees

- Wade-Evans, A. W. (ed.) (1944). Vitae Sanctorum Britanniae et Genealogiae. Cardiff: University of Wales Press Board. (Lives of saints: Bernachius, Brynach. Beuno. Cadocus, Cadog. Carantocus (I and II), Carannog. David, Dewi sant. Gundleius, Gwynllyw. Iltutus, Illtud. Kebius, Cybi. Paternus, Padarn. Tatheus. Wenefred, Gwenfrewi.--Genealogies: De situ Brecheniauc. Cognacio Brychan. Ach Knyauc sant. Generatio st. Egweni. Progenies Keredic. Bonedd y saint.)

Church history

- Brown, H. Miles (1980) The Catholic Revival in Cornish Anglicanism: a study of the Tractarians of Cornwall 1833–1906. St Winnow: H. M. Brown

- Brown, H. Miles (1964) The Church in Cornwall. Truro: Blackford

- Henderson, Charles (1962) The Ecclesiastical History of Western Cornwall. 2 vols. Truro: Royal Institution of Cornwall; D. Bradford Barton, 1962

- Hingeston-Randolph, F. C., ed. Episcopal Registers: Diocese of Exeter. 10 vols. London: George Bell, 1886–1915 (for the period 1257 to 1455)

- Jenkin, A. K. Hamilton (1933) Cornwall and the Cornish: the story, religion and folk-lore of 'The Western Land'. London: J. M. Dent (chapter: The Coming of Wesley)

- Oliver, George (1857) Collections Illustrating the History of the Catholic Religion in the Counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Wilts, and Gloucester; with notices of the Dominican, Benedictine, and Franciscan Orders in England. London: Charles Dolman

- Oliver, George (1846) Monasticon Dioecesis Exoniensis: being a collection of records and instruments illustrating the ancient conventual, collegiate, and eleemosynary foundations, in the Counties of Cornwall and Devon, with historical notices, and a supplement, comprising a list of the dedications of churches in the Diocese, an amended edition of the taxation of Pope Nicholas, and an abstract of the Chantry Rolls [with supplement and index]. Exeter: P. A. Hannaford, 1846, 1854, 1889

- Olson, Lynette (1989) Early Monasteries in Cornwall (Studies in Celtic History series). Woodbridge: Boydell Press ISBN 0-85115-478-6

- Orme, Nicholas (2007) Cornwall and the Cross: Christianity, 500–1560. Chichester: Phillimore in association with the Institute of Historical Research at the University of London ISBN 1-86077-468-7

- Orme, Nicholas (1996) English Church Dedications: with a survey of Cornwall and Devon. Exeter: University of Exeter Press ISBN 0-85989-516-5

- Orme, Nicholas (2010) A History of the County of Cornwall; vol. II: Religious history to 1560. (Victoria County History.)

- Orme, Nicholas, ed. (1991) Unity and Variety: a history of the church in Devon and Cornwall. Exeter: University of Exeter Press ISBN 0-85989-355-3 (A collection of essays examining the character of church life in Devon and Cornwall)

- Pearce, Susan M., ed. (1982) The Early Church in Western Britain and Ireland: studies presented to C. A. Ralegh Radford; arising from a conference organised in his honour by the Devon Archaeological Society and Exeter City Museum. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports

- Pearce, Susan M. (1978). The Kingdom of Dumnonia: Studies in History and Tradition in South-Western Britain A.D. 350–1150. Padstow: Lodenek Press. ISBN 0-902899-68-6.

- Rowse, A. L. (1942) A Cornish Childhood, London: Jonathan Cape (early 20th-century church life)

- Shaw, Thomas (1967) A History of Cornish Methodism. Truro: D. Bradford Barton

- Turner, Sam (2006) Making a Christian landscape: how Christianity shaped the countryside in early-medieval Cornwall, Devon and Wessex. Exeter: University of Exeter Press (as e-book 2015; ISBN 9780859899284}

Antiquities and architecture

- Beacham, Peter & Pevsner, Nikolaus (2014). Cornwall. (The Buildings of England.) New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12668-6; pp. 22–51: "Medieval to mid-seventeenth-century architecture"

- Blight, John Thomas (1872) Ancient Crosses and Other Antiquities in the East of Cornwall 3rd ed. (1872)

- Blight, John Thomas (1856) Ancient Crosses and Other Antiquities in the West of Cornwall (1856), 2nd edition 1858. (A reprint is offered online at Men-an-Tol Studios) (3rd ed. Penzance: W. Cornish, 1872) (facsimile ed. reproducing 1856 ed.: Blight's Cornish Crosses; Penzance : Oakmagic Publications, 1997)

- Brown, H. Miles (1973) What to Look for in Cornish Churches

- Dunkin, E. H. W. (1878) The Church Bells of Cornwall

- Langdon, Arthur G. (1896) Old Cornish Crosses. Truro: J. Pollard

- Meyrick, J. (1982) A Pilgrim's Guide to the Holy Wells of Cornwall. Falmouth: Meyrick

- Okasha, Elisabeth (1993) Corpus of Early Christian Inscribed Stones of South-west Britain. Leicester: University Press

- Sedding, Edmund H. (1909) Norman Architecture in Cornwall: a handbook to old ecclesiastical architecture. With over 160 plates. London: Ward & Co.

- Straffon, Cheryl (1998) Fentynyow Kernow: in search of Cornwall's holy wells. Penzance: Meyn Mamvro ISBN 0-9518859-5-2