Christos Tsountas | |

|---|---|

Χρήστος Τσούντας | |

Photographed in 1879 | |

| Born | 1857 |

| Died | June 9, 1934 (aged 76–77) |

| Nationality | Greek |

| Known for | Study and naming of Cycladic culture |

| Awards |

|

| Academic background | |

| Education | |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Archaeology |

| Sub-discipline | Greek prehistory |

| Institutions | |

| Notable students | |

| Signature | |

Christos Tsountas (Greek: Χρήστος Τσούντας; 1857 – 9 June 1934) was a Greek classical archaeologist. He is considered a pioneer of Greek archaeology and has been called "the first and most eminent Greek prehistorian".[1]

Born in Stenimachos in Thrace in 1857, Tsountas received his university education in Germany, at the universities of Hannover, Munich and Jena. After a brief period working as a teacher, he was hired by the Archaeological Society of Athens as an archaeological official in 1882, and joined the Greek Archaeological Service the following year. He was most active as a field archaeologist in the early decades of his life, carrying out the first archaeological survey of Thessaly, excavating several Mycenaean tombs in Laconia, and carrying out the first formal excavations of the citadel of Mycenae. In the late 1890s, his discoveries in the Cyclades generated the first evidence of Cycladic culture, to which Tsountas gave its name.

Tsountas became a professor of the University of Athens in 1904, from which point he largely retired from practical archaeological work. He published several monographs and textbooks on prehistoric archaeology, including works which became standard works in the field. He moved to the University of Thessaloniki between 1925 and 1926, and died in 1934.

Early life, education and early career

Christos Tsountas was born to a Greek family in 1857[2] in Eastern Rumelia, then part of the Ottoman Empire.[3][lower-alpha 1] His baptismal name may have been Christodoulos or Christopoulos. He grew up in Stenimachos (present-day Asenovgrad); he completed his schooling there, in nearby Philippopolis (present-day Plovdiv) and in Athens.[4] As was common for aspiring Greek archaeologists in the nineteenth century,[5] Tsountas subsequently studied in Germany; initially, he read engineering at the Royal College of Technology in Hannover,[6] before moving to the University of Munich to read philology under the classical archaeologist Heinrich Brunn. He completed his doctoral studies at the University of Jena in 1880.[7]

On returning from Jena, Tsountas taught for a year at the Zariphios School, a Greek school in Philippopolis. In 1882, Tsountas was hired by the Archaeological Society of Athens, a learned society involved in the excavation and conservation of ancient monuments. One of his first postings was in 1882, to the excavations of the British architect Francis Penrose at the Temple of Zeus at Olympia.[7] In the same year, Panagiotis Stamatakis, the Ephor General in charge of the Greek Archaeological Service, invited Tsountas to accompany him on a tour of Boeotia, combatting the illicit trade in antiquities — an event which has been described by the archaeological historian Eleni Konstantinidi-Syvridi as the beginning of Tsountas's apprenticeship to Stamatakis.[8]

In 1883, Tsountas joined the Greek Archaeological Service, during its first major period of expansion. Before 1879, the Service had consisted entirely of the Ephor General, sometimes with an assistant. After the hiring of Panagiotis Kavvadias in 1879 and of Konstantinos Dimitriadis in 1881, Tsountas was recruited by Stamatakis as an ephor alongside Demetrios Philios; they would be joined by Valerios Stais, Vasileios Leonardos and Georgios Lampakis in 1885.[9] On 17 August [O.S. 5 August] 1883, he was promoted to be the Service's ephor for Arta and Aetolia-Acarnania, both in northwestern Greece, but remained in Athens, working for both the Archaeological Service and the Archaeological Society.[7] He was primarily based at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.[4]

Excavations

Most of Tsountas's excavations took place in his early career, with a particular concentration between 1886 and 1908.[1] Between 1880 and 1891, Tsountas excavated in the southern Greek region of Laconia. His excavations there included the tholos tomb at Vapheio; although the tomb had previously been cleared in 1805, Tsountas discovered an intact burial in its floor, with grave goods including the two Vapheio Cups.[10] Tsountas was the first modern archaeologist to excavate and publish a burial in a tholos, demonstrating that the monuments were constructed as tombs and disproving the then-widespread belief that they were constructed as royal treasuries.[11] Tsountas's campaign in Laconia also included the excavation, in 1890, of the Mycenaean shrine known as the Amyklaion.[6] There, he discovered two sculpted heads, known as the "Amyklai Heads", which have been variously dated to the Mycenaean and the Geometric periods, and one of which may have represented the god Apollo.[12]

From 1884, he worked on the Acropolis of Athens.[6] In 1884, he led an underwater survey to investigate the site of the Battle of Salamis, which took place in 480 BCE; though poor weather made the enterprise largely unsuccessful, it may have been the first archaeological work to take place under water.[13] He also excavated at the Mycenaean citadel of Tiryns in the Argolid between 1890 and 1891.[14]

In 1887, Tsountas excavated the looted cemeteries of Tanagra in Boeotia.[7] He worked at Tiryns in 1890–1891,[15] and excavated the tholos tomb at Kambos near Avia in Messenia in 1891, uncovering Minoan-type figurines.[16] Between 1890 and 1892, he assisted Kavvadias, then Ephor General, in cataloguing the prehistoric material in the National Archaeological Museum.[17] Tsountas was made curator of the museum's Mycenaean and Egyptian collections by 1896, by which point he had also written the catalogue for its Mycenaean material.[18]

Mycenae

Following the excavation of Grave Circle A at Mycenae under the German businessman Heinrich Schliemann and Stamatakis in 1876–1877, Tsountas took over the site from May 1886 until 1910.[19] He made the first excavations in the Prehistoric Cemetery around the settlement of Mycenae and carried out the first major excavations of its acropolis,[20] where he uncovered the Great Ramp,[21] cleared the slopes of the citadel and uncovered a large proportion of its buildings.[22] Tsountas's discovery of Ancient Egyptian material, including seven faience plaques bearing the name of the pharaoh Amenhotep III,[23] on the acropolis gave the first definitive evidence of the site's date in the Late Bronze Age (c. 1600 – c. 1200 BCE);[24] it had previously been dated only in vague terms, often described by travellers in terms such as "of the most ancient date", or considered to date to various periods around 1000 BCE.[25]

The main purpose of Tsountas's initial excavations of 1886 was to discover the palatial centre of the site of Mycenae.[26] In that year, he cleared the majority of the citadel, discovering the palace and megaron and excavating the Hellenistic temple built atop the acropolis; he would later remove the temple's remains, as well as most of those from post-Mycenaean periods, to further reveal the Bronze Age palace.[27] In the same year, he excavated on the western slope of the citadel, in the area of a Hellenistic tower, and uncovered a building complex later identified as part of the site's "Cult Centre".[28]

In 1887, Tsountas commenced his excavations of the cemeteries outside the citadel of Mycenae, considering the graves excavated in Circle A to be "royal" and consequently seeking to find what he considered the burials of the rest of the site's population. Between 1887 and 1898, Tsountas excavated 103 chamber tombs and three previously unknown tholos tombs (known as the Tomb of Aegisthus, the Panagia Tholos and the Tomb of the Genii), while he also cleared four tholoi that had already been discovered.[29] In 2006, Tsountas's excavations represented just under half of the total number of chamber tombs excavated at Mycenae, though the sparse documentation made by Tsountas has limited their use for archaeological study.[21]

In 1888, Tsountas made further excavations of the palace, as well as in the eastern part of the citadel, particularly the North East Extension and Mycenae's subterranean cistern,[28] which he discovered.[13] Excavations here continued in 1889, during which time Tsountas made further explorations of the south-western part of the citadel, uncovering a series of buildings over several seasons of work but making little record of them. In 1890, he cleared the northern and north-western slopes of the city; by 1893, he had progressed to the North Gate. In 1895 and 1896, he cleared the eastern and western slopes of the acropolis, and returned in 1896 to the south-western slope. This left unexcavated only a small area on the western slope of the citadel, now known as the "Citadel House" area.[28]

Tsountas's notes on the excavations of the site's chamber tombs were inconsistent, and often left little evidence as to which tomb was being referred to; in the 1990s, the archaeologist Kim Shelton established the correspondence between many of the tombs excavated and numbered by Tsountas and the archaeological remains still visible at the site.[30] His discovery of Egyptian material within the citadel established its date as belonging to the Late Bronze Age.[24] In the late 1880s, he excavated the two tholos tombs known as Kato Phournos and Epano Phournos, which had previously been believed to be gates.[31] In 1891, he excavated the Tomb of Clytemnestra.[32] In contrast to the orthodoxy then prevalent, Tsountas considered the chamber tombs and tholoi at the site to postdate the shaft graves of Circle A.[33] He also disavowed the association, claimed by Schliemann, between the burials at Mycenae and the characters of the Homeric epics.[34] From 1899 to 1903, he was responsible for the consolidation and restoration of the monuments at Mycenae.[35]

Thessaly

_(14595001048).jpg.webp)

The region of Thessaly, in northern Greece, had been the subject of brief and informal antiquarian investigations in the final decades of Ottoman rule prior to 1881. This included visits from foreign antiquarians as well as a study by the medical doctor Nikolaos Georgiades, who published a historical, geographical and topographical study of the region in 1880. The region was incorporated into the Greek state in 1881, and therefore came under the jurisdiction of the Greek Archaeological Service; this development intensified efforts to collect and conserve known antiquities, still largely on an informal basis – the headteachers of local gymnasia would often be designated by the Archaeological Service as "Occasional Collectors of Antiquities" and organise small collections of portable finds, sometimes working alongside foreign scholars such as the German archaeologist Habbo Gerhard Lolling.[36] The Archaeological Service occasionally sent representatives to conduct rescue excavations, as did the Archaeological Society of Athens, which established several local collections of artefacts, including one in a primary school at Larissa which included 166 objects.[37]

In 1889, Tsountas, who was by then the Head of Antiquities for the Archaeological Society, made the first systematic archaeological investigation of the area.[38] His first excavation was that of a Mycenaean burial tumulus at Marmariani.[3] In the course of excavating five Mycenaean tombs at the site,[39] he uncovered levels of settlement deposits dating to the Neolithic period, providing the first evidence of Neolithic material in Greece and demonstrating that mounds of this kinds, known as magoules, could be tells formed from the deposited layers of settlements of successive periods.[38] Tsountas subsequently excavated Mycenaean tombs at the mound known as Kastron (ancient Iolkos) near Volos in 1900,[3] at Volos itself in 1901–1903,[40] and at Sesklo from 1901 to 1902. His colleague Stais had conducted excacations at Dimini in 1901–1902; Stais subsequently withdrew from Thessaly to focus on his work in Attica, and Tsountas received permission from him and the Archaeological Society to carry on the excavation of Dimini. In 1903, he uncovered three defensive walls at the site.[41] Volos, Sesklo and Dimini subsequently became considered type sites for the Neolithic period in Greece.[42] Tsountas continued to visit and conduct field survey in Thessaly each summer until 1906.[41]

Cyclades and other islands

Tsountas was one of the first archaeologists to excavate in the Cycladic Islands.[45] In September 1894, he excavated the cemetery of Amorgos, an island already known for its quantity of prehistoric remains, including graves dating to the Early and Middle Bronze Age.[46] He was guided by a local priest, Dimitrios Prasinos, who had previously directed other archaeological visitors to the island and sold low-value antiquities to foreign archaeologists, including Duncan Mackenzie.[47] During a short visit to the island, Tsountas discovered that the island's two largest cemeteries, at Kapros and Dokathismata, had been extensively looted by illegal excavators, among whom he named Prasinos and Ioannis Palailogos. Palailogos was arrested in September 1894 for smuggling looted antiquities from Amorgos to Athens, and Tsountas was called to make a report on the smuggled goods.[48] In 1897, Tsountas excavated the cemetery of Krasades on Antiparos.[49]

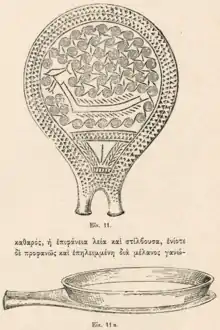

Tsountas coined the term Cycladic culture after his research of 1898–1899.[50] In those two years,[51] he excavated cemetery of Chalandriani and the associated fortified settlement of Kastri on the island of Syros.[52] He also excavated several hundred other Cycladic graves in cemeteries on the islands of Siphnos, Paros and Despotiko.[53] On Siphnos, he excavated the site of Agios Andreas, uncovering the site's double circuit walls with its towers.[54] Tsountas published his findings from the Cyclades in the Archaeological Journal, a scholarly publication of the Archaeological Society of Athens: his 1898 article may have been the first systematic study of the economic life of an archaeological site, though his conclusion that fish played only a small role in the Cycladic diet has since been overturned.[55]

Tsountas excavated frequently on the island of Euboea, which he considered an important influence on the Cycladic Syros culture.[56] In 1885, he excavated the necropolis to the west of the ancient city of Eretria.[57] In 1886, 1891 and 1892, Tsountas made further excavations of the cemeteries around the city, which had been looted by antiquities traders;[7] from 1886 onwards, he also supervised excavations undertaken by private landowners on their own land near Eretria.[57] He worked on Euboea again in 1903, excavating six tombs at the cemetery of Manika near Chalkis.[58] In March–May 1905,[lower-alpha 2] Tsountas made a 46-day visit to Crete, then an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire, at the request of the board of the Archaeological Society, surveying its archaeological remains.[60] He was assisted by Stefanos Xanthoudidis, the Ephor of Antiquities for Crete; Iosif Chatzidakis, the founder of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum; Arthur Evans, the archaeologist of the Minoan palace of Knossos; and Harriet Boyd, who had discovered and excavated the site of Gournia.[59] The following year, the Cretan government accepted a request from the Archaeological Society for an excavation at the site of Malia: the project was due to begin in the same year under Tsountas.[61]

Later career

On 24 February [O.S. 11 February] 1904,[lower-alpha 3] Tsountas was elected as Professor of the History of Ancient Art of the University of Athens; Kavvadias was also elected to a professorship on the same occasion.[63] According to the archaeologist Christos Karouzos, who studied under Tsountas, he was reluctant to accept the post, but was persuaded to do so by the university.[64] His appointment largely marked the end of his career as an excavator: from 1904, he focused his academic work on teaching and writing.[65] Between 1909 and 1911, he served as secretary of the Archaeological Society of Athens.[6]

In February 1919, Tsountas was appointed as a founding professor of the "Practical School of Art History", an archaeological training centre administered by the Archaeological Society on behalf of the Greek government.[66] The school's thirty-six students in its first year included Karouzos, Semni Papaspyridi and Spyridon Marinatos, all of whom went on to become leading figures in twentieth-century Greek archaeology.[67] Tsountas has been credited as a particular influence on Papaspyridi, and marked one of the examination papers necessary for her to join the Archaeological Service in 1921.[68] Encouraged by Arthur Evans, Tsountas granted permission for the British archaeologist Alan Wace to excavate at Mycenae in the early 1920s. Wace subsequently excavated in the Tomb of Aegisthus, which Tsountas had discovered in 1892, and throughout the site of Mycenae: his investigations confirmed several of Tsountas's theories as to the chronology of the site and the nature of Mycenaean civilisation.[69] Another of Tsountas's students was George E. Mylonas, who would later direct the excavation of Mycenae between 1957 and 1985.[70]

Tsountas retired from the University of Athens in 1925, though taught for the 1925–1926 academic year at the University of Thessaloniki.[71] In 1926, he was made a member of the Academy of Athens, Greece's national academy.[72] He died in 1934.[50] The place of his burial is unknown: the historian Eleni Manteli has suggested that the Greek state likely neglected to organise a funeral or memorial for him.[73]

Beliefs about Greek culture

Tsountas believed that Greek culture had existed in a continuous form since the prehistoric period, developing the ideas of historians such as Constantine Paparrigopoulos,[65] who had sought in the mid-nineteenth century to challenge the then-popular view that the population of modern Greece had no biological or cultural descent from that of the classical period.[74] Though he did not engage in the contemporary debate as to the geographic origins of the Mycenaean population, he reconstructed a rivalry between Mycenae and Troy which he described as part of the "eternal Eastern Question", connecting the mythical Trojan War with the Greco-Persian Wars of the classical period and the Greek War of Independence.[75]

Tsountas argued in particular that Mycenaean civilisation was fundamentally Greek,[1] and directed his reconstruction of prehistory towards the construction of contemporary Greek national identity. Though such efforts were common among Greek archaeologists of the nineteenth century, by the end of the century, Tsountas was one of extremely few who continued to espouse Romantic nationalism and to view his archaeological work through its paradigm.[76] Tsountas argued that the Mycenaeans had originally been immigrants from northern Europe, with genetic commonalities with the Germans, Celts and Italians.[77] Like other archaeologists and folklorists of his day, such as the German Arthur Milchhöfer and the French Georges Perrot, Tsountas assessed the cultural continuity of Greece through perceived similarities in vernacular customs and architecture; he drew attention, for example, to the similar shape of hearths found in Mycenaean dwellings and modern Greek peasant homes.[78]

Tsountas was relatively unusual among Greek intellectuals of his time in considering the Byzantine period – then generally viewed as a period of foreign domination – a vital part of the Greek national narrative.[79] The historiographical debate over the role of Byzantium in Greek history was partly played out through the Greek language question: the national debate as to whether Greek should be spoken in the prestige katharevousa dialect, which attempted to minimise post-classical features in favour of those found in Ancient Greek, or in the demotic dialect, which represented the natural language of most Greeks and implied an acceptance of the changes in the language that took place, inter alia, during the Byzantine period.[80] In 1914, Tsountas appeared as a witness in the Nafplio Trial, a court case over the closure of a girls' school which had broken educational norms by teaching in demotic instead katharevousa; Tsountas testified in favour of the use of demotic.[81] His positive views of the Byzantine period were unpopular within the Archaeological Society of Athens, described by the historian Fani Mallouchou-Tufano as "an intransigent ideological exponent of pure Classicism", which generally neglected the study of Byzantine archaeology in favour of that of the classical period.[82]

Assessment and legacy

In an obituary of Tsountas published in the newspaper Nea Estia, his former student Karouzos described him as an "excellent teacher ... [and] modest man" with a "Socratic" appearance.[81] The French archaeologist Charles Picard, a former director of the French School at Athens, similarly described him as "an enthusiastic savant, modest and courteous ... [who] always showed a most generous attitude towards the foreign schools of archaeology".[83]

Recognition and honours

On 24 November [O.S. 12 November] 1892, Tsountas was awarded the Silver Cross of the Order of the Redeemer, Greece's national order of merit, for services to archaeology. He was awarded the Prussian Order of the Red Eagle (fourth class) on 20 February [O.S. 8 February] 1900, and the Gold Cross of the Order of the Redeemer on 3 September [O.S. 22 August] 1914.[65] He was made an honorary member of the British Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies.[84] The part of the Cult Centre which he excavated in 1886 is known as "Tsountas's House" after him.[85]

Reception of Tsountas's archaeological work

Tsountas has been considered an underappreciated figure in Aegean archaeology, particularly by comparison to non-Greek archaeologists such as Schliemann, Wace and Evans.[86] The archaeologist Sofia Voutsaki has named Tsountas as a pioneer of Greek archaeology and called him "the first and most eminent Greek prehistorian".[1] The archaeologist Jack Davis has judged that Tsountas had greater influence on the field of Greek prehistory than any other archaeologist.[87] According to the historian Cathy Gere, Tsountas is "the individual who properly deserves the title of Father of the Greek Bronze Age".[88] Shelton has particularly credited Tsountas with taking the site of Mycenae and Mycenaean civilisation "out of Schliemann's spotlight".[22] His excavations in Thessaly have been credited by the archaeologist Curtis Runnels as the beginning of the systematic investigation of the Greek Stone Age.[89]

Tsountas popularised the term Mycenaean to refer to the civilisation of the Greek mainland in the Late Bronze Age.[90] His book Mycenae and the Mycenaean Age, first published in 1893,[50] became a standard textbook on Greek prehistory.[1] He is credited with establishing Thessaly as the primary locus of research into Neolithic Greece,[50] while his work in the Cyclades has been recognised with beginning the study of the prehistoric period in those islands.[49] He also played a large role in the formation of the National Archaeological Museum's collection of prehistoric artefacts.[18]

Tsountas's views of Mycenaean civilisation as fundamentally Greek were initially at odds with the prevailing opinion in scholarship outside Greece, which variously saw the burials in Grave Circle A – before Tsountas's work, considered the totality of evidence for Mycenaean civilisation – as belonging to Near Eastern, Egyptian, Slavic or northern-European cultures. The German philologist Ulrich Köhler, who directed the German Archaeological Institute at Athens, described them as having "nowhere a trace of the Greek spirit, nor of any Greek customs and beliefs", and as of "an exclusively oriental character".[91]

Tsountas has been criticised for underestimating the value of pottery as archaeological evidence, and for throwing away ceramic material during his excavations.[34] In most cases, he retained only finds of metal and of stone, as well as intact vases – which were extremely rare – and discarded the remainder.[92] Though he kept notebooks during his excavations of Mycenae, averaging approximately ten pages of notes for every month of his work,[92] he often excavated without keeping a journal and without the use of photography. The archaeological historian Vassiliki Pliatsika has written that modern archaeological standards, such as the systematic recording of finds and their contexts, are "deafeningly absent" from Tsountas's reports.[93] Since Tsountas's excavations, studies of the spoil created by them has revealed important potsherds, representing substantial fragments of vessels as well as evidence for the later occupation of Mycenae after the end of the Bronze Age.[94]

Tsountas's hypothesis that Mycenae's multiple cemeteries reflected an original pattern of settlement in disparate villages, first advanced in his 1888 article on the excavation of Mycenae's tombs, became the accepted model for Mycenae and for Mycenaean civilisation in general, but was disproved by further study in the early 1990s.[95] His assertion that Mycenaean society was illiterate was overturned by the discovery of Linear B tablets at Pylos in 1939, and subsequently, under Alan Wace, at Mycenae in 1952.[96] Tsountas also argued that Mycenaean society had been matriarchal and that Mycenaean religion had been based around a "goddess of generation". By the late nineteenth century, this view was widely accepted, though it has since been overturned.[97]

Selected works

In 1893, Tsountas published Mycenae and the Mycenaean Civilisation, which was expanded and translated into English in collaboration with the American classicist J. Irving Manatt as The Mycenaean Age: A Study of the Monuments and Culture of Pre-Homeric Greece in 1897.[34] Tsountas's book was the first to attempt a synthesis of Mycenaean civilisation (though the available evidence limited Tsountas to investigating southern Greece), drawing on material from Mycenae alongside that from additional sites, including Tiryns and Tsountas's own excavations at Vapheio.[22] He also published annual reports of his excavations at Mycenae in the Proceedings of the Archaeological Society of Athens, as well as occasional articles in the society's journal, the Archaeological Journal (Greek: Ἀρχαιολογικὴ Ἐφημερίς, romanized: Archaiologiki Efimeris).[92]

His published works include:

As sole author

- Tsountas, Christos (1888). Ἀνασκαφαὶ τάφων ἐκ Μυκηνῶν [Excavations of Tombs from Mycenae]. Ἀρχαιολογικὴ Ἐφημερίς (in Greek): 119–180.

- — (1898). Κυκλαδικά [Cycladic Matters]. Ἀρχαιολογικὴ Ἐφημερίς (in Greek): 137–212.

- — (1908). Αί προΐστορικαί Ακροπόλεις Διµηνίου και Σέσκλου [The Prehistoric Acropolises of Dimini and Sesklo] (in Greek). Athens: Sakellarios. OCLC 1053678917.

As co-author

- Tsountas, Christos; Manatt, J. Irving (1897). The Mycenaean Age: A Study of the Monuments and Culture of Pre-Homeric Greece. London: Macmillan. OCLC 1402927063.

Footnotes

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Tsountas's birthplace is generally given as Stenimachos (present-day Asenovgrad in Bulgaria), but contemporaries also recorded it as Philippopolis (present-day Plovdiv in Bulgaria).[4]

- ↑ Published sources disagree as to whether the journey took place in 1903 or 1905, though Tsountas's journal dates it to 1905, making this the most likely possibility in the view of the archaeological historian Katia Manteli.[59]

- ↑ Greece adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1923; 28 February [O.S. 15 February] was followed by 1 March.[62] In this article, this date and all subsequent dates are given in the 'New Style' Gregorian calendar, while dates before it are given in the 'Old Style' Julian calendar.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Voutsaki 2017, p. 130.

- ↑ Muskett 2014, p. 43; Manteli 2021, p. 309.

- 1 2 3 Gallis 1979, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Pliatsika 2020, p. 291.

- ↑ Petrakos 2015, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 Panagiotopoulos 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Masouridi 2017, p. 148.

- ↑ Konstantinidi-Syvridi 2020, p. 285.

- ↑ Petrakos 2011, p. 4.

- ↑ Gere 2006, p. 102; Panagiotopoulos 2015.

- ↑ Gere 2006, p. 102.

- ↑ Langdon 1998, pp. 253–254.

- 1 2 Muskett 2014, p. 43.

- ↑ Davis 2022, p. 101, n. 22; Masouridi 2017, p. 148 (for the date).

- ↑ Masouridi 2013, p. 30.

- ↑ Marabea 2010, p. 427.

- ↑ Guzzetti 2012, p. 144; Kalessopoulou 2021, p. 326.

- 1 2 Manteli 2021, p. 312.

- ↑ Voutsaki 2017, p. 130; Masouridi 2017, p. 148; Shelton 2006, p. 159 (for the dates); Shelton 2006, p. 163 (for the Great Ramp).

- ↑ Shelton 2010, p. 25.

- 1 2 Shelton 2006, p. 163.

- 1 2 3 Shelton 2006, p. 159.

- ↑ Kelder 2009, p. 346.

- 1 2 Moore, Rowlands & Karadimas 2014, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Moore, Rowlands & Karadimas 2014, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Klein 1997, p. 250.

- ↑ Shelton 2006, pp. 160–161.

- 1 2 3 Shelton 2006, p. 161.

- ↑ Shelton 2006, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Burns 2010, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Moore, Rowlands & Karadimas 2014, p. 69.

- ↑ Moore, Rowlands & Karadimas 2014, p. 78.

- ↑ Galanakis 2007, p. 242.

- 1 2 3 Gere 2006, p. 97.

- ↑ Pliatsika 2020, p. 296.

- ↑ Gallis 1979, p. 2.

- ↑ Gallis 1979, pp. 2–3.

- 1 2 Krahtopoulou et al. 2020, p. 25.

- ↑ Runnels 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Gallis 1979, p. 3; Masouridi 2017, p. 148.

- 1 2 Gallis 1979, p. 4.

- ↑ Voutsaki 2017, p. 130; Muskett 2014, p. 44 (for the dates).

- ↑ Tsountas 1898, p. 86.

- ↑ Galanakis 2013, p. 191.

- ↑ Muskett 2014, p. 43. The French archaeologist Gaston Deschamps excavated on Amorgos in 1888, the first person to do so there with governmental permission.[44]

- ↑ Galanakis 2013, pp. 182–184.

- ↑ Galanakis 2013, pp. 190–192. Mackenzie is better known as a collaborator of Arthur Evans at Knossos: on which, see MacGillivray 2000, pp. 171–172.

- ↑ Galanakis 2013, p. 193.

- 1 2 Delvoye 1947, p. 48.

- 1 2 3 4 Muskett 2014, p. 44.

- ↑ Thimme 1977, p. 185.

- ↑ Fitton 1999, p. 8.

- ↑ Fitton 1999, p. 8; Muskett 2014, p. 44.

- ↑ Caskey 1958, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Mylona 2003, p. 193. The article is Tsountas 1898.

- ↑ Sapouna-Sakellarakis 1987, p. 264.

- 1 2 Rous, Huguenot & Gerin 2017, p. 9.

- ↑ Sapouna-Sakellarakis 1987, p. 233.

- 1 2 Manteli 2021, p. 310.

- ↑ Manteli 2021, p. 307.

- ↑ Manteli 2021, p. 308.

- ↑ Kiminas 2009, p. 23.

- ↑ Christodoulou 2009, pp. 106–107; Pliatsika 2020, p. 292 (for Tsountas's title).

- ↑ Karouzos 1934, p. 564. For the context of the debate over demotic and katharevousa, see Greek language question.

- 1 2 3 Pliatsika 2020, p. 292.

- ↑ Petrakos 1995, pp. 120–121. Petrakos gives the school's name in Greek, as Πρακτικῆς Σχολῆς τῆς ἱστορίας τῆς τέχνης.

- ↑ Petrakos 1995, p. 122.

- ↑ Nikolaidou & Kokkinidou 2005, pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Galanakis 2007, p. 240.

- ↑ Vogeikoff-Brogan 2020 (for Mylonas's study under Tsountas); Shelton 2010, p. 26 (for Mylonas at Mycenae).

- ↑ Robinson & Blegen 1935, p. 379.

- ↑ Masouridi 2017, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Manteli 2021, p. 313.

- ↑ Hamilakis & Yalouri 1999, p. 129; Curta 2011, p. 1.

- ↑ Gere 2006, p. 107.

- ↑ Voutsaki 2017, p. 131.

- ↑ Voutsaki 2017, p. 133.

- ↑ Voutsaki 2017, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Voutsaki 2017, p. 132 (for Tsountas's beliefs). For the wider perception of Byzantium at the time, see Marano 2019, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Marano 2019, p. 77.

- 1 2 Karouzos 1934, p. 564.

- ↑ Voutsaki 2017, p. 137. Mallouchou-Tufano's quotation is from Mallouchou-Tufano 2007, p. 49.

- ↑ Picard 1934, p. 185. For Picard's career, see Delbo 2002, pp. 230–231.

- ↑ Masouridi 2017, p. 149.

- ↑ Shelton 2006, p. 161; Muskett 2014, p. 43.

- ↑ Traill 1996, p. 139.

- ↑ Davis 2022, p. 101, n. 22.

- ↑ Gere 2006, p. 96.

- ↑ Runnels 2008, p. 9.

- ↑ Davis 2022, p. 9.

- ↑ Voutsaki 2017, p. 132; Voutsaki quotes Köhler from Köhler 1878, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Shelton 2006, p. 160.

- ↑ Pliatsika 2020, p. 295.

- ↑ Shelton 2006, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Shelton 2006, pp. 161–162. The article is Tsountas 1888.

- ↑ Fitton 1996, p. 106. For Pylos, see Tracy 2018, p. 13; for Mycenae, see Gill 2004.

- ↑ Gere 2006, pp. 105–106.

Works cited

- Burns, Bryan E. (2010). Mycenaean Greece, Mediterranean Commerce, and the Formation of Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11954-2.

- Caskey, John L. (1958). "Excavations at Lerna, 1957". Hesperia. 27 (2): 125–144. doi:10.2307/147056. JSTOR 147056.

- Christodoulou, Georgios (2009). Ο Ν. Γ. Πολίτης και η αρχαιολογία στο Πανεπιστήμιο Αθηνών [N. G. Politis and Archaeology at the University of Athens] (PDF). Mentor (in Greek). 93: 106–107. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- Curta, Florin (2011). The Edinburgh History of the Greeks, c. 500 to 1050. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4489-6.

- Davis, Jack L. (2022). A Greek State in Formation: The Origins of Civilisation in Mycenaean Pylos. Vol. 75. Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-38724-9. JSTOR j.ctv2rb75vw.

- Delbo, Charlotte (2002) [1965]. Le Convoi du 24 janvier [The Convoy of 24 January] (in French). Paris: Éditions de Minuit. ISBN 978-2-7073-1638-7.

- Delvoye, Charles (1947). "Quatre vases préhelléniques du Musée Archéologique de Charleroi" [Four Pre-Hellenic Vases in the Archaeological Museum of Charleroi]. L'Antiquité Classique (in French). 16 (1): 47–58. JSTOR 41642997.

- Fitton, J. Lesley (1996). The Discovery of the Greek Bronze Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-21188-9.

- Fitton, J. Lesley (1999). Cycladic Art. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2160-4.

- Galanakis, Yannis (2007). "The Construction of the Aegisthus Tholos Tomb at Mycenae and the 'Helladic Heresy'". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 102: 239–256. doi:10.1017/S0068245400021481. JSTOR 30245251. S2CID 162590402.

- Galanakis, Yannis (2013). "Early Prehistoric Research on Amorgos and the Beginnings of Cycladic Archaeology". American Journal of Archaeology. 117 (2): 181–205. JSTOR 10.3764/aja.117.2.0181.

- Gallis, Constantinos (1979). "A Short Chronicle of the Greek Archaeological Investigations in Thessaly, from 1881 Until the Present Day". In Bruno, Helly (ed.). La Thessalie: Actes de la Table-Ronde, 21-24 juillet 1975. Lyon: Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée. pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-2-35668-034-1. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- Gere, Cathy (2006). The Tomb of Agamemnon: Mycenae and the Search for a Hero. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-86197-617-8.

- Gill, David (2004). "Wace, Alan John Bayard (1879–1957)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/74552. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Guzzetti, Andrea (2012). A Walk through the Past: Toward the Study of Archaeological Museums in Italy, Greece, and Israel (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). Bryn Mawr College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- Hamilakis, Yannis; Yalouri, Eleana (1999). "Sacralising the Past: Cults of Archaeology in Modern Greece". Archaeological Dialogues. 6 (2): 115–135. doi:10.1017/S138020380000146X. ISSN 1478-2294. S2CID 145214423.

- Kalessopoulou, Despina (2021). "The First National Museum of Modern Greece". In Lagogianni-Georgakarakos, Maria; Koutsogiannis, Thodoris (eds.). These Are What We Fought For: Antiquities and the Greek War of Independence. Athens: Archaeological Resources Fund. pp. 314–332. ISBN 978-960-386-441-7.

- Karouzos, Christos (15 June 1934). Χρήστος Τσούντας [Christos Tsountas]. Nea Estia (in Greek). 180: 564. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- Kelder, Jorrit M. (2009). "Royal Gift Exchange between Mycenae and Egypt: Olives as 'Greeting Gifts' in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean". American Journal of Archaeology. 113 (3): 339–352. JSTOR 20627592.

- Kiminas, Demetrius (2009). The Ecumenical Patriarchate. San Bernardino: The Borgo Press. ISBN 978-1-4344-5876-6.

- Klein, Nancy L. (1997). "Excavation of the Greek Temples at Mycenae by the British School at Athens". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 92: 247–322. doi:10.1017/S0068245400016701.

- Köhler, Ulrich (1878). "Über die Zeit und den Ursprung der Grabanlagen in Mykene und Spata" [On the Date and the Origin of the Grave Complexes in Mycenae and Spata]. Archäologische Mitteilungen (in German). 3: 3–13.

- Konstantinidi-Syvridi, Eleni (2020). "Panagiotis Stamatakis: "Valuing the ancient monuments of Greece as sacred wealth…"". In Lagogianni-Georgakarakos, Maria; Koutsogiannis, Thodoris (eds.). These Are What We Fought For: Antiquities and the Greek War of Independence. Athens: Archaeological Resources Fund. pp. 276–289. ISBN 978-960-386-441-7.

- Krahtopoulou, Athanasia; Frederick, Charles; Orengo, Hector A.; Dimoula, Anastasia; Saridaki, Niki; Kyrillidou, Stella; Livarda, Alexandra; Garcia-Molsosa, Arnau (2020). "Re-Discovering the Neolithic Landscapes of Western Thessaly, Central Greece". In Blanco-González, Antonio; Kienlin, Tobias L. (eds.). Current Approaches to Tells in the Prehistoric Old World: A Cross-Cultural Comparison from Early Neolithic to the Iron Age. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 25–40. ISBN 978-1-78925-489-1.

- Langdon, Susan (1998). "Significant Others: The Male–Female Pair in Greek Geometric Art". American Journal of Archaeology. 102 (2): 251–270. JSTOR 506468.

- MacGillivray, Joseph Alexander (2000). Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth. New York: Hill and Wang (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). ISBN 978-0-8090-3035-4.

- Mallouchou-Tufano, Fani (2007). "The Vicissitudes of the Athenian Acropolis in the Nineteenth Century: From Castle to Monument". In Valavanis, Panos (ed.). Great Moments in Greek Archaeology. Athens: Kapon Press. pp. 36–57. ISBN 978-0-89236-910-2.

- Manteli, Katia (2021). "Christos Tsountas in the Cretan State In the Early 20th Century: Through the Archives of the National Archaeological Museum". In Lagogianni-Georgakarakos, Maria; Koutsogiannis, Thodoris (eds.). These Are What We Fought For: Antiquities and the Greek War of Independence. Athens: Archaeological Resources Fund. pp. 306–313. ISBN 978-960-386-441-7.

- Marabea, Christina (2010). "The Tholos Tomb at Kambos, Avia: Excavation by Christos Tsountas, 1891". In Cavanagh, Helen; Cavanagh, William; Roy, James (eds.). Honouring the Dead in the Peloponnese: Proceedings of the Conference Held at Sparta, 23–25 April 2009. Nottingham: Centre for Spartan and Peloponnesian Studies. pp. 427–440. OCLC 802570703.

- Marano, Yuri Alessandro (2019). "'Ours Once More'? Byzantine Archaeology and the Construction of Greek National Identity". In Gelichi, Sauro (ed.). Archeologia Medievale, XLVI, 2019 – Prima dell'Archeologia pubblica. Identità, conflitti sociali e Medioevo nella ricerca del Mediterraneo. Florence: Edizioni all'Insegna del Giglio. pp. 75–96. ISBN 978-88-7814-926-7.

- Masouridi, Stavroula (2013). 1885–1909. Η Υπηρεσία στα χρόνια του Π. Καββαδία [1885–1909: The Service in the Period of P. Kavvadias]. In Kontouri, Elena; Masouridi, Stavroula (eds.). Ιστορίες επί χάρτου: Μορφές και θέματα της Αρχαιολογίας στην Ελλάδα του 19ου αιώνα [Histories on Paper: Modalities and Themes of Archaeology in Greece in the Nineteenth Century] (PDF) (in Greek). Athens: Ministry of Culture and Sport. pp. 28–33. ISBN 978-960-386-138-6. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- Masouridi, Stavroula (2017). Χρήστος Τσούντας 1857–1934: Ερευνητικό, δημιουργικό και πειθαρχημένο πνεύμα [Christos Tsountas 1857–1934: Inquisitive, Creative and Disciplined Spirit] (PDF). Θέματα Αρχαιολογίας [Topics in Archaeology] (in Greek). 1 (1): 148–149. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- Moore, Dudley; Rowlands, Edward; Karadimas, Nektarios (2014). In Search of Agamemnon: Early Travellers to Mycenae. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-5776-5.

- Muskett, Georgina (2014). "The Aegean World". In Bahn, Paul (ed.). The History of Archaeology: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 39–56. ISBN 978-1-317-99942-3.

- Mylona, Dimitra (2003). "Archaeological Fish Remains in Greece: General Trends of the Research and a Gazetteer of Sites". British School at Athens Studies. 9: 193–200. JSTOR 40960346.

- Nikolaidou, Marianna; Kokkinidou, Dimitria (2005). "Greek Women in Archaeology: An Untold Story". Excavating Women: A History of Women in European Archaeology. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-72776-6.

- Panagiotopoulos, Diamantis (2015). "Tsountas, Christos". In Kuhlmann, Peter; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.). Geschichte der Altertumswissenschaften: Biographisches Lexikon. Der Neue Pauly Supplemente I Online. Vol. 6. doi:10.1163/2452-3054_dnpo6_COM_00711.

- Petrakos, Vasileios (1995). Η Περιπέτεια της ελληνικής αρχαιολογίας στον βίο του Χρήστου Καρούζου [The Adventure of Greek Archaeology in the Life of Christos Karouzos] (PDF) (in Greek). Athens: Archaeological Society of Athens. ISBN 960-7036-47-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- Petrakos, Vasileios (2011). Η εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. Οι Αρχαιολόγοι και οι Ανασκαφές 1837–2011 (Κατάλογος Εκθέσεως) [The Archaeological Society of Athens. The Archaeologists and the Excavations 1837–2011 (Exhibition Catalogue)] (in Greek). Athens: Archaeological Society of Athens. ISBN 978-960-8145-86-3.

- Petrakos, Vasileios (2015). Ὁ πολιτικὸς Μαρινᾶτος [The Political Marinatos] (PDF). Mentor. 114: 16–49. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Picard, Charles (1934). "Christos Tsountas (1857—1934)". Revue Archéologique (in French). 4: 184–185. JSTOR 41748388.

- Pliatsika, Vassiliki (2020). "Journal Pages from the Archaeological Life of Christos Tsountas at Mycenae". In Lagogianni-Georgakarakos, Maria; Koutsogiannis, Thodoris (eds.). These Are What We Fought For: Antiquities and the Greek War of Independence. Athens: Archaeological Resources Fund. pp. 290–305. ISBN 978-960-386-441-7.

- Robinson, David M.; Blegen, Elizabeth Pierce (1935). "Archaeological News and Discussions". American Journal of Archaeology. 39 (3): 378–411. JSTOR 498626.

- Rous, Isabelle Hasselin; Huguenot, Caroline; Gerin, Dominique (2017). "Offrandes Hellénistiques en minature: le mobilier d'une tombe d'enfant d'Érétrie conservé au Musée du Louvre" [Hellenistic Offerings in Miniature: The Assemblage of a Child's Tomb from Eretria Conserved at the Louvre Museum]. Revue Archéologique (in French). 1: 3–63. JSTOR 44710355.

- Runnels, Curtis (2008). "George Finlay's Contributions to the Discovery of the Stone Age in Greece". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 103: 9–25. JSTOR 30245260.

- Sapouna-Sakellarakis, Efi (1987). "New Evidence from the Early Bronze Age Cemetery at Manika, Chalkis". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 82: 233–264. JSTOR 30103092.

- Shelton, Kim (2006). "The Long Lasting Effect of Tsountas on the Study of Mycenae". In Darcque, Pascal; Fotiadis, Michael; Polychronopoulou, Olga (eds.). Mythos: La préhistoire égéenne du XIXe au XXIe siècle après J.-C. Actes de la table ronde internationale d’Athènes (21-2 novembre 2002). Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique Suppléments. Vol. 46. Athens: French School at Athens. pp. 159–164. ISBN 2-86958-195-5.

- Shelton, Kim (2010). "Mycenae: Archaeology of Mycenae". In Gagarin, Michael (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 23–28. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195170726.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-517072-6.

- Thimme, Jürgen (1977). Art and Culture of the Cyclades: Handbook of an Ancient Civilisation. Karlsruhe: C. F. Müller. ISBN 978-3-7880-9573-4.

- Tracy, Stephen V. (2018). "The Acceptance of the Greek Solution for Linear B". Hesperia. 87 (1): 1–16. doi:10.2972/hesperia.87.1.0001. JSTOR 10.2972/hesperia.87.1.0001. S2CID 186486561.

- Traill, David J. (1996). "The Discovery of the Greek Bronze Age. By J. Lesley Fitton. Cambridge MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1996. Pp. 212. Cloth. $29". The Classical Outlook. 73 (4): 139. JSTOR 43937886.

- Vogeikoff-Brogan, Natalia (19 April 2020). "Forgotten Friend of Skyros: Hazel Dorothy Hansen (Part I)". From the Archivist's Notebook. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- Voutsaki, Sofia (2017). "The Hellenization of the Prehistoric Past: The Search for Greek Identity in the Work of Christos Tsountas". In Voutsaki, Sofia; Cartledge, Paul (eds.). Ancient Monuments and Modern Identities: A Critical History of Archaeology in 19th and 20th Century Greece. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 130–147. ISBN 978-1-315-51344-7.