Church music in Scotland includes all musical composition and performance of music in the context of Christian worship in Scotland, from the beginnings of Christianisation in the fifth century, to the present day. The sources for Scottish Medieval music are extremely limited due to factors including a turbulent political history, the destructive practices of the Scottish Reformation, the climate and the relatively late arrival of music printing. In the early Middle Ages, ecclesiastical music was dominated by monophonic plainchant, which led to the development of a distinct form of liturgical Celtic chant. It was superseded from the eleventh century by more complex Gregorian chant. In the High Middle Ages, the need for large numbers of singing priests to fulfill the obligations of church services led to the foundation of a system of song schools, to train boys as choristers and priests. From the thirteenth century, Scottish church music was increasingly influenced by continental developments. Monophony was replaced from the fourteenth century by the Ars Nova consisting of complex polyphony. Survivals of works from the first half of the sixteenth century indicate the quality and scope of music that was undertaken at the end of the Medieval period. The outstanding Scottish composer of the first half of the sixteenth century was Robert Carver, who produced complex polyphonic music.

The Reformation had a severe impact on church music. The song schools of the abbeys, cathedrals and collegiate churches were closed down, choirs disbanded, music books and manuscripts destroyed and organs removed from churches. The Lutheranism that influenced the early Scottish Reformation attempted to accommodate Catholic musical traditions into worship. Later the Calvinism that came to dominate was much more hostile to Catholic musical tradition and popular music, placing an emphasis on what was biblical, which meant the Psalms and most church compositions were confined to homophonic settings. James VI attempted to revive the song schools, however, the triumph of the Presbyterians in the National Covenant of 1638 led to and end of polyphony. In the eighteenth century Evangelicals tended to believe only the Psalms of the 1650 Psalter should be used in the services in the church, while the Moderates attempted to expand psalmody in the Church of Scotland to include hymns the singing of other scriptural paraphrases. Lining out began to be abandoned in favour of singing stanza by stanza. In the second half of the eighteenth century these innovations became linked to a choir movement that included the setting up of schools to teach new tunes and singing in four parts. More tune books appeared and the repertory further expanded.

The nineteenth century saw the reintroduction of accompanied music into the Church of Scotland, influenced by the Oxford Movement. Organs began to be added to churches from the mid-nineteenth century, but they remained controversial and were never placed in some churches. Hymns were also adopted by the main denominations. The American Evangelists Ira D. Sankey and Dwight L. Moody helped popularise accompanied church music in Scotland. In the Scottish Episcopal Church, the Oxford Movement and links with the Anglican Church led to the introduction of more traditional services and by 1900 surpliced choirs and musical services were the norm. In Episcopalian cathedrals and churches that maintain a choral tradition, the repertoire of Anglican church music continues to play an important part of worship.

In the twentieth century ecumenical movements including the Iona Community and the Dunblane Consultations on church music, were highly influential on church music throughout Britain and the United States and there was a return to the composition of choral music.

Middle Ages

Sources

The sources for Scottish Medieval music are extremely limited. These limitations are the result of factors including a turbulent political history, the destructive practices of the Scottish Reformation, the climate[1] and the relatively late arrival of music printing.[2] What survives are occasional indications that there was a flourishing musical culture. There are no major musical manuscripts for Scotland from before the twelfth century.[1] Neither does Scottish music have an equivalent of the Bannatyne Manuscript in poetry, giving a large and representative sample of Medieval work.[2] The oldest extant piece of Church music written in Scotland is in the Inchcolm Fragment.[3] Musicologist John Purser has suggested that the services dedicated to St. Columba in this manuscript and the similar service in the Sprouston Breviary, dedicated to St. Kentigern, may preserve some of this earlier tradition of plain chant.[1] Other early manuscripts include the Dunkeld Music Book and the Scone Antiphoner.[3] The most important collection is the mid-thirteenth century Wolfenbüttel 677 or W1 manuscript, which survives only because it was appropriated from St Andrews Cathedral Priory and taken to the continent in the 1550s. Other sources include occasional written references in accounts and in literature and visual representations of musicians and instruments.[1] The limitations on the survival of Medieval musical manuscripts is partly because of the relatively late development of printing in Scotland, which would mean that only from the mid-sixteenth century do large numbers of printed works survive.[2]

Early Middle Ages

In the early Middle Ages, ecclesiastical music was dominated by monophonic plainchant.[4] The development of British Christianity, separate from the direct influence of Rome until the eighth century, with its flourishing monastic culture, led to the development of a distinct form of liturgical Celtic chant.[5] Although no notations of this music survive, later sources suggest distinctive melodic patterns.[5] Celtic chant is thought have been superseded from the eleventh century, as elsewhere in Europe, by more complex Gregorian chant.[6] The version of this chant linked to the liturgy as used in the Diocese of Salisbury, the Sarum Use, first recorded from the thirteenth century, became dominant in England[7] and was the basis for most surviving chant in Scotland.[1] It was closely related to Gregorian chant, but it was more elaborate and with some unique local features. The Sarum rite continued to be the basis of Scottish liturgical music in Scotland until the Reformation and where choirs were available, which was probably limited to the great cathedrals, collegiate churches and the wealthier parish churches it would have been used in the main ingredient of divine offices of vespers, compline, matins, lauds, mass and the canonical hours.[1]

High Middle Ages

In the High Middle Ages, the need for large numbers of singing priests to fulfill the obligations of church services led to the foundation of a system of song schools, to train boys as choristers and priests, often attached to Cathedrals, wealthy monasteries and collegiate churches.[1] The proliferation of collegiate churches and requiem masses in the later Middle Ages would have necessitated the training of large numbers of choristers, marking a considerable expansion of the song school system. Over 100 collegiate churches of secular priests were founded in Scotland between 1450 and the Reformation.[8] They were designed to provide masses for their founders and their families, who included the nobility and the emerging orders of the Lords of Parliament and the wealthy merchants of the developing burghs.[1] From the thirteenth century, Scottish church music was increasingly influenced by continental developments, with figures like the musical theorist Simon Tailler studying in Paris, before returned to Scotland where he introduced several reforms of church music.[9] The Wolfenbüttel 677 manuscript contains a large number of French compositions, particularly from Notre Dame de Paris, beside inventive pieces by unknown Scottish composers.[1]

Late Middle Ages

Monophony was replaced from the fourteenth century by the Ars Nova, a movement that developed in France and then Italy, replacing the restrictive styles of Gregorian plainchant with complex polyphony.[10] The tradition was well established in England by the fifteenth century.[4] The distinctive English version of polyphony, known as the Contenance Angloise (English manner), used full, rich harmonies based on the third and sixth, which was highly influential in the fashionable Burgundian court of Philip the Good, where the Burgundian School associated with Guillaume Dufay developed.[11] In the late fifteenth century a series of Scottish musicians trained in the Netherlands before returning home, including John Broune, Thomas Inglis and John Fety, the last of whom became master of the song school in Aberdeen and then Edinburgh, introducing the new five-fingered organ playing technique.[12] Survivals of works from the first half of the sixteenth century from St. Andrews and St. Giles, Edinburgh, and post-Reformation works from composers that were trained in this era from the abbeys of Dunfermline and Holyrood, and from the priory at St. Andrews, indicate the quality and scope of music that was undertaken at the end of the Medieval period.[1]

Renaissance

The outstanding Scottish composer of the first half of the sixteenth century was Robert Carver (c. 1488–1558), a canon of Scone Abbey. His complex polyphonic music could only have been performed by a large and highly trained choir such as the one employed in the Scottish Chapel Royal. James V was also a patron to figures including David Peebles (c. 1510–79?), whose best known work "Si quis diligit me" (text from John 14:23), is a motet for four voices. These were probably only two of many accomplished composers from this era, whose work has largely only survived in fragments.[13] Much of what survives of church music from the first half of the sixteenth century is due to the diligent work of Thomas Wode (d. 1590), vicar of St Andrews, who compiled a part book from now lost sources, which was continued by unknown hands after his death.[14]

Impact of the Reformation

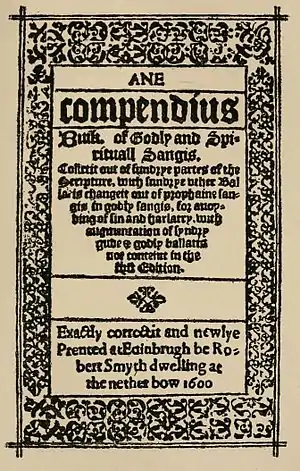

The Reformation had a severe impact on church music. The song schools of the abbeys, cathedrals and collegiate churches were closed down, choirs disbanded, music books and manuscripts destroyed and organs removed from churches.[15] The Lutheranism that influenced the early Scottish Reformation attempted to accommodate Catholic musical traditions into worship, drawing on Latin hymns and vernacular songs. The most important product of this tradition in Scotland was The Gude and Godlie Ballatis (1567), which were spiritual satires on popular ballads composed by the brothers James, John and Robert Wedderburn. Never adopted by the kirk, they nevertheless remained popular and were reprinted from the 1540s to the 1620s.[16]

Later the Calvinism that came to dominate the Scottish Reformation was much more hostile to Catholic musical tradition and popular music, placing an emphasis on what was biblical, which meant the Psalms. The Scottish Psalter of 1564 was commissioned by the Assembly of the Church. It drew on the work of French musician Clément Marot, Calvin's contributions to the Strasbourg Psalter of 1539 and English writers, particularly the 1561 edition of the Psalter produced by William Whittingham for the English congregation in Geneva. The intention was to produce individual tunes for each psalm, but of 150 psalms 105 had proper tunes and in the seventeenth century, common tunes, which could be used for psalms with the same metre, became more frequent. Because whole congregations would now sing these psalms, unlike the trained choirs who had sung the many parts of polyphonic hymns,[16] there was a need for simplicity and most church compositions were confined to homophonic settings.[17]

During his personal reign James VI attempted to revive the song schools, with an act of parliament passed in 1579, demanding that councils of the largest burghs set up "ane sang scuill with ane maister sufficient and able for insturctioun of the yowth in the said science of musik". Five new schools were opened within four years of the act and by 1633 there were at least twenty-five. Most of those without song schools made provision within their grammar schools.[18] Polyphony was incorporated into editions of the Psalter from 1625, but usually with the congregation singing the melody and trained singers the contra-tenor, treble and bass parts.[16] However, the triumph of the Presbyterians in the National Covenant of 1638 led to the end of polyphony and a new psalter in common metre, but without tunes, was published in 1650.[1] In 1666 The Twelve Tunes for the Church of Scotland, composed in Four Parts, which actually contained 14 tunes and was designed for use with the 1650 Psalter, was first published in Aberdeen. It would go through five editions by 1720. By the late seventeenth century these two works had become the basic corpus of the tunes sung in the kirk.[19]

Eighteenth century

In the eighteenth century there were growing divisions in the kirk between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party.[20] While Evangelicals emphasised the authority of the Bible and the traditions and historical documents of the kirk, the Moderates tended to stress intellectualism in theology, the established hierarchy of the kirk and attempted to raise the social status of the clergy.[21] In music the evangelicals tended to believe that only the Psalms of the 1650 Psalter should be used in the services in the church. In contrast the Moderates believed that Psalmody was in need of reform and expansion.[19] This movement had its origins in the influence of English psalmondist and hymnodist Isaac Watts (1674–1748) and became and attempt to expand psalmondy in the Church of Scotland to include hymns the singing of other scriptural paraphrases.[22]

From the late seventeenth century the common practice was lining out, by which the precentor sang or read out each line and it was then repeated by the congregation. From the second quarter of the eighteenth century it was argued that this should be abandoned in favour of the practice of singing stanza by stanza. This necessitated the use of practice verses and the pioneering work was Thomas Bruce's The Common Tunes, or, Scotland's Church Musick Made Plane (1726), which contained seven practice verses. The 30 tunes in this book marked the beginning of a renewal movement in Scottish Psalmody. New practices were introduced and the repertory was expanded, including both neglected sixteenth-century settings and new ones.[19] In the second half of the eighteenth century these innovations became linked to a choir movement that included the setting up of schools to teach new tunes and singing in four parts.[23] More tune books appeared and the repertory further expanded, although there were still fewer than in counterpart churches in England and the US. More congregations abandoned lining out.[19]

In the period 1742–45 a committee of the General Assembly worked on a series of paraphrases, borrowing from Watts, Philip Doddridge (1702–51) and other Scottish and English writers, which were published as Translations and Paraphrases, in verse, of several passages of Sacred Scripture (1725). These were never formally adopted, as the Moderates, then dominant in the church, thought they were too evangelical. A corrected version was licensed for private use in 1751 and some individual congregations petitioned successful for their use in public worship and they were revised again and published 1781.[22] These were formally adopted by the assembly, but there was considerable resistance to their introduction in some parishes.[24]

After the Glorious Revolution episcopalianism retrained supporters, but they were divided between the "non-jurors", not subscribing to the right of William III and Mary II, and later the Hanoverians, to be monarchs,[25] and Qualified Chapels, where congregations, led by priests ordained by bishops of the Church of England or the Church of Ireland, were willing to pray for the Hanoverians.[26] Such chapels drew their congregations from English people living in Scotland and from Scottish Episcopalians who were not bound to the Jacobite cause and used the English Book of Common Prayer. They could worship openly and installed organs and hired musicians, following practice in English parish churches, singing in the liturgy as well as metrical psalms, while the non-jurors had to worship covertly and less elaborately. The two branches united in the 1790s after the death of the last Stuart heir in the main line and the repeal of the penal laws in 1792. The non-juring branch soon absorbed the musical and liturgical traditions of the qualified churches.[27]

Catholicism had been reduced to the fringes of the country, particularly the Gaelic-speaking areas of the Highlands and Islands. Numbers probably reduced in the seventeenth century and organisation had deteriorated.[20] Clergy entered the country secretly and although services were illegal they were maintained.[28] The provisions of the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791, which allowed freedom of worship for Catholics who took an oath of allegiance, were extended to Scotland in 1793 and provided some official toleration.[29] Worship, in chapels within the houses of members of the aristocracy or adapted buildings was deliberately low key. It typically involved an unsung Low Mass in Latin. Any form of musical accompaniment was prohibited by George Hay, who was vicar apostolic of the Lowland District in the period 1778 to 1805.[30]

Nineteenth century

The nineteenth century saw the reintroduction of accompanied music into the Church of Scotland. This was strongly influenced by the English Oxford Movement, which encouraged a return to Medieval forms of architecture and worship. The first organ to be installed by a Church of Scotland church after the Reformation was at St. Andrews, Glasgow in 1804, but it was not in the church building and was used only for weekly rehearsals. Two years later the city council was petitioned to allow it to be moved into the church, but they deferred to the local presbytery, who decided, after much deliberation, that they were illegal and prohibited their use within their jurisdiction. In 1828 the first organ was controversially installed in an Edinburgh church. Around the same time James Steven published his Harmonia Sacra: A Selection of the Most Approved Psalm and Hymn Tunes, provocatively printed a frontispiece showing a small organ.[31] The Church Service Society was founded in 1865 to promote liturgical study and reform and a year later organs were officially admitted to churches.[32] They began to be added to churches in large numbers and by the end of the century roughly a third of Church of Scotland ministers were members of the society and over 80 per cent of kirks had both organs and choirs. However, they remained controversial, with considerable opposition among conservative elements within the church[33] and organs were never placed in some churches.[31]

Similarly, when the Scottish Episcopal Church was able to rebuild after the last post-1688 Penal Laws were finally lifted in 1792, the lingering Anglo-Catholic influence of both the Jacobite Non-juring schism and the later Oxford Movement led to the reintroduction of High Church services and, by 1900, of surpliced choirs and harmonied musical services.[34] A similar pattern occurred following the success of the 1780-1829 campaign for Catholic Emancipation. As the Catholic Church also left the catacombs and began to rebuild after centuries of religious persecution. Music was reintroduced into the Tridentine Mass and organs began being placed in churches during the early 19th century. By 1820 there were organs in churches in seven towns.[30] For Catholics in the Gàidhealtachd, Fr. Allan MacDonald (1859-1905) anonymously published hymnals in the Scottish Gaelic language at Oban in 1889 and 1893. John Lorne Campbell has since meticulously documented the origins of each hymn in both collections. Some, Fr. MacDonald had collected from those of his parishioners who were well-versed in the oral tradition. Others were his own compositions and literary translations.[35]

Furthermore, as both a musical accompaniment for Low Mass and as an alternative to Calvinist worship - particularly the 17th-century practice of unaccompanied Gaelic psalm singing and precenting the line - Fr. MacDonald also composed a series of sung Gaelic paraphrases of Catholic doctrine about what is taking place during the Tridentine Mass. These paraphrases continued to be routinely sung during Mass upon Benbecula, Barra, South Uist and Eriskay until the aftermath of the Second Vatican Council. Even though the same basic melodies were used by Catholic Gaels on every island, each parish developed its own distinctive style of singing them.[36]

The sung liturgical texts and the tunes were both transcribed based on recordings made during the 1970s at St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church in Daliburgh, South Uist. They were published for the first time with musical notation in the 2002 bilingual Mungo Books edition of Fr. Allan MacDonald's poetry and songs.[37]

The Free Church that broke away from the kirk in 1843 in the Great Disruption, was more conservative over music, and organs were not permitted until 1883.[38]

Hymns were first introduced in the United Presbyterian Church in the 1850s. They became common in the Church of Scotland and Free Church in the 1870s. The Church of Scotland adopted a hymnal with 200 songs in 1870 and the Free Church followed suit in 1882.[38] The visit of American Evangelists Ira D. Sankey (1840–1908), and Dwight L. Moody (1837–99) to Edinburgh and Glasgow in 1874–75 helped popularise accompanied church music in Scotland. The Moody-Sankey hymnbook remained a best seller into the twentieth century.[39] Sankey made the harmonium so popular that working-class mission congregations pleaded for the introduction of accompanied music.[40]

Twentieth century

In the early twentieth century the Catholic Church in Scotland formalised the use of hymns, with the publication of The Book of Tunes and Hymns (1913), the Scottish equivalent of the Westminster Hymnal.[41] The foundation of the ecumenical Iona Community in 1938, on the island of Iona off the coast of Scotland, led to a highly influential form of music, which was used across Britain and the US. Leading musical figure John Bell (b. 1949) adapted folk tunes or created tunes in a folk style to fit lyrics that often emerged from the spiritual experience of the community.[42] The Dunblane consultations, informal meetings at the ecumenical Scottish Church House in Dunblane in 1961–69, attempted to produce modern hymns that retained theological integrity. They resulted in the British "Hymn Explosion" of the 1960s, which produced multiple collections of new hymns.[43] The growth of a tradition of classical music in Scotland also led to a renewed interest in choral works. Over 30 have been created by James MacMillan (b. 1959), including his St. Anne's Mass (1985), which calls for congregational participation and his Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis (2000) for orchestra and choir.[44]

See also

- Fr. Allan MacDonald

- Gaelic psalm singing

- Hymnody in the Anglosphere (article in German)

- Tàladh Chrìosda

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 J. R. Baxter, "Music, ecclesiastical", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 431–2.

- 1 2 3 J. R. Baxter, "Culture: Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1560)", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 130–33.

- 1 2 C. R. Borland, A Descriptive Catalogue of The Western Medieval Manuscripts in Edinburgh University Library (University of Edinburgh Press, 1916), p. xv.

- 1 2 R. McKitterick, C. T. Allmand, T. Reuter, D. Abulafia, P. Fouracre, J. Simon, C. Riley-Smith, M. Jones, eds, The New Cambridge Medieval History: C. 1415- C. 1500 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), ISBN 0521382963, pp. 319–25.

- 1 2 D. O. Croinin, ed., Prehistoric and Early Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland, vol I (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), ISBN 0199226652, p. 798.

- ↑ D. Hiley, Western Plainchant: a Handbook (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), ISBN 0198165722, p. 483.

- ↑ E. Foley, M. Paul Bangert, Worship Music: a Concise Dictionary (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2000), ISBN 0415966477, p. 273.

- ↑ J. P. Foggie, Renaissance Religion in Urban Scotland: The Dominican Order, 1450–1560 (BRILL, 2003), ISBN 9004129294, p. 101.

- ↑ K. Elliott and F. Rimmer, A History of Scottish Music (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1973), ISBN 0563121920, pp. 8–12.

- ↑ W. Lovelock, A Concise History of Music (New York NY: Frederick Ungar, 1953), p. 57.

- ↑ R. H. Fritze and W. B. Robison, Historical Dictionary of Late Medieval England, 1272–1485 (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2002), ISBN 0313291241, p. 363.

- ↑ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 58 and 118.

- ↑ J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, p. 118.

- ↑ J. R. Baxter, "Culture: Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1560)", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 130–2.

- ↑ A. Thomas, "The Renaissance", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0191624330, pp. 198–9.

- 1 2 3 J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 187–90.

- ↑ A. Thomas, "The Renaissance", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0191624330, p. 198.

- ↑ G. Munro, "'Sang schools' and 'music schools': music education in Scotland 1560–1650", in S. F. Weiss, R. E. Murray, Jr., and C. J. Cyrus, eds, Music Education in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (Indiana University Press, 2010), ISBN 0253004551, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 B. D. Spinks, A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons (Scarecrow Press, 2009), ISBN 0810869810, pp. 143–4.

- 1 2 J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5 (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 416–7.

- ↑ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 303–4.

- 1 2 B. D. Spinks, A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons (Scarecrow Press, 2009), ISBN 0810869810, p. 28.

- ↑ B. D. Spinks, A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons (Scarecrow Press, 2009), ISBN 0810869810, p. 26.

- ↑ B. D. Spinks, A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons (Scarecrow Press, 2009), ISBN 0810869810, p. 32.

- ↑ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 252–3.

- ↑ N. Yates, Eighteenth-Century Britain: Religion and Politics 1714–1815 (London: Pearson Education, 2008), ISBN 1405801611, p. 49.

- ↑ R. M. Wilson, Anglican Chant and Chanting in England, Scotland, and America, 1660 to 1820 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), ISBN 0198164246, p. 192.

- ↑ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 298–9.

- ↑ T. Gallagher, Glasgow: The Uneasy Peace : Religious Tension in Modern Scotland, 1819–1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987), ISBN 0719023963, p. 9.

- 1 2 N. Yates, Preaching, Word and Sacrament: Scottish Church Interiors 1560–1860 (A&C Black, 2009), ISBN 0567031411, p. 94.

- 1 2 B. D. Spinks, A Communion Sunday in Scotland ca. 1780: Liturgies and Sermons (Scarecrow Press, 2009), ISBN 0810869810, p. 149.

- ↑ R. W. Munro, "Churches: 2 1843–1929" in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 91–2.

- ↑ S. J. Brown, "Scotland and the Oxford Movement", in S. J. Brown, Peter B. Nockles and Peter Benedict Nockles, eds, The Oxford Movement: Europe and the Wider World 1830–1930 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), ISBN 1107016444, p. 73.

- ↑ D. W. Bebbington, "Episcopalian community" in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 234–5.

- ↑ Edited by Ronald Black (2002), Eilein na h-Òige: The Poems of Fr. Allan MacDonald, Mungo Press. Page 503.

- ↑ Edited by Ronald Black (2002), Eilein na h-Òige: The Poems of Fr. Allan MacDonald, Mungo Press. Pages 90-101, 488-491.

- ↑ Edited by Ronald Black (2002), Eilein na h-Òige: The Poems of Fr. Allan MacDonald, Mungo Press. Page 488.

- 1 2 S. J. Brown, "Beliefs and religions" in T. Griffiths and G. Morton, A History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1800 to 1900 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), ISBN 0748621709, p. 122.

- ↑ P. Maloney, Scotland and the Music Hall, 1850–1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), ISBN 0719061474, p. 197.

- ↑ T. M. Devine, The Scottish Nation: A Modern History (London: Penguin, 2012), ISBN 0718196732.

- ↑ T. E. Muir, Roman Catholic Church Music in England, 1791–1914: A Handmaid of the Liturgy? (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2013), ISBN 1409493830.

- ↑ D. W. Music, Christian Hymnody in Twentieth-Century Britain and America: an Annotated Bibliography (London: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001), ISBN 0313309035, p. 10.

- ↑ D. W. Music, Christian Hymnody in Twentieth-Century Britain and America: an Annotated Bibliography (London: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001), ISBN 0313309035, p. 3.

- ↑ M. P. Unger, Historical Dictionary of Choral Music (Scarecrow Press, 2010), ISBN 0810873923, p. 271.