In music theory, a comma is a very small interval, the difference resulting from tuning one note two different ways.[1] Strictly speaking, there are only two kinds of comma, the syntonic comma, "the difference between a just major 3rd and four just perfect 5ths less two octaves", and the Pythagorean comma, "the difference between twelve 5ths and seven octaves".[2] The word comma used without qualification refers to the syntonic comma,[3] which can be defined, for instance, as the difference between an F♯ tuned using the D-based Pythagorean tuning system, and another F♯ tuned using the D-based quarter-comma meantone tuning system. Intervals separated by the ratio 81:80 are considered the same note because the 12-note Western chromatic scale does not distinguish Pythagorean intervals from 5-limit intervals in its notation. Other intervals are considered commas because of the enharmonic equivalences of a tuning system. For example, in 53TET, B![]() ♭ and A♯ are both approximated by the same interval although they are a septimal kleisma apart.

♭ and A♯ are both approximated by the same interval although they are a septimal kleisma apart.

Etymology

Translated in this context, "comma" means "a hair" as in "off by just a hair". The word "comma" came via Latin from Greek κόμμα, from earlier *κοπ-μα: "the result or effect of cutting". A more complete etymology is given in the article κόμμα (Ancient Greek) in the Wiktionary.

Description

Within the same tuning system, two enharmonically equivalent notes (such as G♯ and A♭) may have a slightly different frequency, and the interval between them is a comma. For example, in extended scales produced with five-limit tuning an A♭ tuned as a major third below C5 and a G♯ tuned as two major thirds above C4 are not exactly the same note, as they would be in equal temperament. The interval between those notes, the diesis, is an easily audible comma (its size is more than 40% of a semitone).

Commas are often defined as the difference in size between two semitones. Each meantone temperament tuning system produces a 12-tone scale characterized by two different kinds of semitones (diatonic and chromatic), and hence by a comma of unique size. The same is true for Pythagorean tuning.

.PNG.webp) Lesser diesis defined in quarter-comma meantone as difference between semitones (m2 − A1), or interval between enharmonically equivalent notes (from C♯ to D♭). The interval from C to D is narrower than in Pythagorean tuning (see below). .PNG.webp) Pythagorean comma (PC) defined in Pythagorean tuning as difference between semitones (A1 − m2), or interval between enharmonically equivalent notes (from D♭ to C♯). The interval from C to D is wider than in quarter-comma meantone (see above). |

In just intonation, more than two kinds of semitones may be produced. Thus, a single tuning system may be characterized by several different commas. For instance, a commonly used version of five-limit tuning produces a 12-tone scale with four kinds of semitones and four commas.

The size of commas is commonly expressed and compared in terms of cents – 1⁄1200 fractions of an octave on a logarithmic scale.

Commas in different contexts

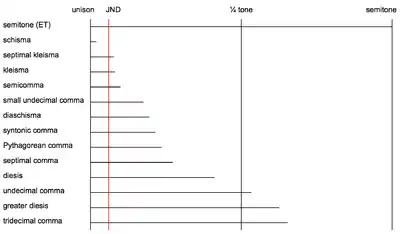

In the column below labeled "Difference between semitones", min2 is the minor second (diatonic semitone), aug1 is the augmented unison (chromatic semitone), and S1, S2, S3, S4 are semitones as defined here. In the columns labeled "Interval 1" and "Interval 2", all intervals are presumed to be tuned in just intonation. Notice that the Pythagorean comma (PC) and the syntonic comma (SC) are basic intervals that can be used as yardsticks to define some of the other commas. For instance, the difference between them is a small comma called schisma. A schisma is not audible in many contexts, as its size is narrower than the smallest audible difference between tones (which is around six cents, also known as just-noticeable difference, or JND).

| Name of comma | Alternative Name | Definitions | Size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference between semitones |

Difference between commas |

Difference between | Cents | Ratio | |||

| Interval 1 | Interval 2 | ||||||

| Schisma | Skhisma | aug1 − min2 in 1 / 12 comma meantone | 1 PC − 1 SC | 8 perfect fifths + 1 major third | 5 octaves | 1.95 | 32805:32768 |

| Septimal kleisma | 3 major thirds | 1 Octave − 1 septimal comma | 7.71 | 225:224 | |||

| Kleisma | 6 minor thirds | Tritave (1 octave + 1 perfect fifth) | 8.11 | 15625:15552 | |||

| Small undecimal comma[4] | 1 neutral second | 1 Minor tone | 17.40 | 100:99 | |||

| Diaschisma | Diaskhisma | min2 − aug1 in 1 / 6 comma meantone, S3 − S2 in 5-limit tuning | 2 SC − 1 PC | 3 octaves | 4 perfect fifths + 2 major thirds | 19.55 | 2048:2025 |

| Syntonic comma (SC) | Didymus' comma | S2 − S1 in 5 limit tuning | 4 perfect fifths | 2 octaves + 1 major third | 21.51 | 81:80 | |

| Major tone | Minor tone | ||||||

| 53 TET comma (κ53) | 1 step in 53 TET | 1 / 9 Major tone in 53 TET | 1 / 5 minor tone in 53 TET | 22.6 | 1200:53 | ||

| Pythagorean comma (PC) | Ditonic comma | aug1 − min2 in Pythagorean tuning | 12 perfect fifths | 7 octaves | 23.46 | 531441:524288 | |

| Septimal comma[5] | Archytas' comma | Minor seventh | Septimal minor seventh | 27.26 | 64:63 | ||

| Diesis | Lesser diesis diminished second | min2 − aug1 in 1 / 4 comma meantone, S3 − S1 in 5 limit tuning | 3 SC − 1 PC | Octave | 3 major thirds | 41.06 | 128:125 |

| Undecimal comma[5][6] | Undecimal quarter-tone | Undecimal tritone | Perfect fourth | 53.27 | 33:32 | ||

| Greater diesis | min2 − aug1 in 1 / 3 comma meantone, S4 − S1 in 5 limit tuning | 4 SC − 1 PC | 4 minor thirds | Octave | 62.57 | 648:625 | |

| Tridecimal comma | Tridecimal third-tone | Tridecimal tritone | Perfect fourth | 65.34 | 27:26 | ||

Many other commas have been enumerated and named by microtonalists.[7]

The syntonic comma has a crucial role in the history of music. It is the amount by which some of the notes produced in Pythagorean tuning were flattened or sharpened to produce just minor and major thirds. In Pythagorean tuning, the only highly consonant intervals were the perfect fifth and its inversion, the perfect fourth. The Pythagorean major third (81:64) and minor third (32:27) were dissonant, and this prevented musicians from freely using triads and chords, forcing them to write music with relatively simple texture. Musicians in late Middle Ages recognized that by slightly tempering the pitch of some notes, the Pythagorean thirds could be made consonant. For instance, if you decrease by a syntonic comma (81:80) the frequency of E, C–E (a major third) and E–G (a minor third) become just: C–E is flattened by a just ratio of

and at the same time E–G is sharpened to the just ratio of

This led to the creation of a new tuning system, known as quarter-comma meantone, which permitted the full development of music with complex texture, such as polyphonic music, or melodies with instrumental accompaniment. Since then, other tuning systems were developed, and the syntonic comma was used as a reference value to temper the perfect fifths throughout the family of syntonic temperaments, including meantone temperaments.

Alternative definitions

In quarter-comma meantone, and any kind of meantone temperament tuning system that tempers the fifth to a size smaller than 700 cents, the comma is a diminished second, which can be equivalently defined as the difference between:

- minor second and augmented unison (also known as diatonic and chromatic semitones), or

- major second and diminished third, or

- minor third and augmented second, or

- major third and diminished fourth, or

- perfect fourth and augmented third, or

- augmented fourth and diminished fifth, or

- perfect fifth and diminished sixth, or

- minor sixth and augmented fifth, or

- major sixth and diminished seventh, or

- minor seventh and augmented sixth, or

- major seventh and diminished octave.

In Pythagorean tuning, and any kind of meantone temperament tuning system that tempers the fifth to a size larger than 700 cents (such as 1 / 12 comma meantone), the comma is the opposite of a diminished second, and therefore the opposite of the above-listed differences. More exactly, in these tuning systems the diminished second is a descending interval, while the comma is its ascending opposite. For instance, the Pythagorean comma (531441:524288, or about 23.5 cents) can be computed as the difference between a chromatic and a diatonic semitone, which is the opposite of a Pythagorean diminished second (524288:531441, or about −23.5 cents).

In each of the above-mentioned tuning systems, the above-listed differences have all the same size. For instance, in Pythagorean tuning they are all equal to the opposite of a Pythagorean comma, and in quarter comma meantone they are all equal to a diesis.

Notation

In the years 2000–2004, Marc Sabat and Wolfgang von Schweinitz worked together in Berlin to develop a method to exactly indicate pitches in staff notation. This method was called the extended Helmholtz-Ellis JI pitch notation.[8] Sabat and Schweinitz take the "conventional" flats, naturals and sharps as a Pythagorean series of perfect fifths. Thus, a series of perfect fifths beginning with F proceeds C G D A E B F♯ and so on. The advantage for musicians is that conventional reading of the basic fourths and fifths remains familiar. Such an approach has also been advocated by Daniel James Wolf and by Joe Monzo, who refers to it by the acronym HEWM (Helmholtz-Ellis-Wolf-Monzo).[9] In the Sabat-Schweinitz design, syntonic commas are marked by arrows attached to the flat, natural or sharp sign, septimal commas using Giuseppe Tartini's symbol, and undecimal quartertones using the common practice quartertone signs (a single cross and backwards flat). For higher primes, additional signs have been designed. To facilitate quick estimation of pitches, cents indications may be added (downward deviations below and upward deviations above the respective accidental). The convention used is that the cents written refer to the tempered pitch implied by the flat, natural, or sharp sign and the note name. One of the great advantages of any such a notation is that it allows the natural harmonic series to be precisely notated. A complete legend and fonts for the notation (see samples) are open source and available from Plainsound Music Edition. Thus a Pythagorean scale is C D E F G A B C, while a just scale is C D E![]() F G A

F G A ![]() B

B![]() C.

C.

Composer Ben Johnston uses a "−" as an accidental to indicate a note is lowered a syntonic comma, or a "+" to indicate a note is raised a syntonic comma;[10] however, Johnston's "basic scale" (the plain nominals A B C D E F G) is tuned to just-intonation and thus already includes the syntonic comma. Thus a Pythagorean scale is C D E+ F G A+ B+ C, while a just scale is C D E F G A B.

Tempering of commas

Commas are frequently used in the description of musical temperaments, where they describe distinctions between musical intervals that are eliminated by that tuning system. A comma can be viewed as the distance between two musical intervals. When a given comma is tempered out in a tuning system, the ability to distinguish between those two intervals in that tuning is eliminated. For example, the difference between the diatonic semitone and chromatic semitone is called the diesis. The widely used 12-tone equal temperament tempers out the diesis, and thus does not distinguish between the two different types of semitones. On the other hand, 19-tone equal temperament does not temper out this comma, and thus it distinguishes between the two semitones.

Examples:

- 12-TET tempers out the diesis, as well as a variety of other commas.

- 19-TET tempers out the septimal diesis and syntonic comma, but does not temper out the diesis.

- 22-TET tempers out the septimal comma of Archytas, but does not temper out the septimal diesis or syntonic comma.

- 31-TET tempers out the syntonic comma, as well as the comma defined by the ratio (99:98), but does not temper out the diesis, septimal diesis, or septimal comma of Archytas.

The following table lists the number of steps used that correspond various just intervals in various tuning systems. Zeros indicate that the interval is a comma (i.e. is tempered out) in that particular equal temperament.

| Interval | 5-TEDO | 7-TEDO | 12-TEDO | 19-TEDO | 22-TEDO | 31-TEDO | 34-TEDO | 41-TEDO | 53-TEDO | 72-TEDO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2/1 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 19 | 22 | 31 | 34 | 41 | 53 | 72 | ||

| 15/8 | 5 | 6 | 11 | 17 | 20 | 28 | 31 | 37 | 48 | 65 | ||

| 9/5 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 16 | 19 | 26 | 29 | 35 | 45 | 61 | ||

| 7/4 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 15 | 18 | 25 | 28 | 33 | 43 | 58 | ||

| 5/3 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 14 | 16 | 23 | 25 | 30 | 39 | 53 | ||

| 8/5 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 21 | 23 | 28 | 36 | 49 | ||

| 3/2 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 13 | 18 | 20 | 24 | 31 | 42 | ||

| 10/7 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 16 | 17 | 21 | 27 | 37 | ||

| 64/45 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 16 | 17 | 21 | 27 | 37 | ||

| 45/32 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 15 | 17 | 20 | 26 | 35 | ||

| 7/5 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 15 | 17 | 20 | 26 | 35 | ||

| 4/3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 13 | 14 | 17 | 22 | 30 | ||

| 9/7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 15 | 19 | 26 | ||

| 5/4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 17 | 23 | ||

| 6/5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 19 | ||

| 7/6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 16 | ||

| 8/7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 14 | ||

| 9/8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 12 | ||

| 10/9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 11 | ||

| 27/25 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | ||

| 15/14 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | ||

| 16/15 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | ||

| 21/20 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 25/24 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 648/625 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 28/27 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 36/35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 128/125 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 49/48 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 50/49 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 64/63 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 531441/524288 | 1 | -1 | 0 | -1 | 2 | -1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 81/80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2048/2025 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 126/125 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1728/1715 | 0 | -1 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 2109375/2097152 | 3 | -2 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 0 | -1 | ||

| 15625/15552 | 2 | -1 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 225/224 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 32805/32768 | 1 | -1 | 0 | -1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | -1 | ||

| 2401/2400 | -1 | 2 | 1 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 4375/4374 | -1 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

The comma can also be considered as the interval that remains after a full circle of intervals. The Pythagorean comma, for instance, is the difference obtained, say, between A♭ and G♯ after a circle of twelve just fifths. A circle of three just major thirds, such as A♭–C–E–G♯, produces the small diesis 125/128 (41,1 cent) between G♯ and A♭. A circle of four just minor thirds, such as G♯–B–D–F–A♭, produces an interval of 648/625 between A♭ and G♯. Etc. An interesting property of temperaments is that this difference remains whatever the tuning of the intervals forming the circle.[11] In this sense, commas and other minute intervals can never be completely tempered out, whatever the tuning.

Comma sequence

A comma sequence defines a musical temperament through a unique sequence of commas at increasing prime limits.[12] The first comma of the comma sequence is in the q-limit, where q is the nth odd prime, and n is the number of generators. Subsequent commas are in prime limits, each one prime beyond the last.

Other intervals called commas

There are also several intervals called commas, which are not technically commas because they are not rational fractions like those above, but are irrational approximations of them. These include the Holdrian and Mercator's commas.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ Waldo Selden Pratt (1922). Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Vol. 1, p. 568. John Alexander Fuller Maitland, Sir George Grove, eds. Macmillan.

- ↑ Clive Greated (2001). "Comma", Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.06186

- ↑ Benson, Dave (2006). Music: A Mathematical Offering, p. 171. ISBN 0-521-85387-7.

- ↑ Haluška, Ján (2003). The Mathematical Theory of Tone Systems. p. xxvi. ISBN 0-8247-4714-3.

- 1 2 Rasch, Rudolph (2000). "A word or two on the tunings of Harry Partch". In Dunn, David (ed.). Harry Partch: An anthology of critical perspectives. p. 34. ISBN 90-5755-065-2. — Describes difference between 11 limit and 3 limit intervals.

- ↑ Rasch, Rudolph (1988). "Farey systems of musical intonation". In Benitez, J.M.; et al. (eds.). Listening. Vol. 2. p. 40. ISBN 3-7186-4846-6. — Source for 32:33 as difference between 11:16 & 2:3.

- ↑ List of commas, by prime limit in the Xenharmonic wiki

- ↑ see article "The Extended Helmholtz-Ellis JI Pitch Notation: eine Notationsmetode für dienatürlichen Intervalle" in Mikrotöne und mehr – Auf György Ligetis Hamburger Pfaden, ed. Manfred Stahnke, von Bockel Verlag, Hamburg 2005 ISBN 3-932696-62-X

- ↑ Tonalsoft Encyclopaedia article about 'HEWM' notation

- ↑ John Fonville. "Ben Johnston's Extended Just Intonation – A Guide for Interpreters", p. 109, Perspectives of New Music, vol. 29, no. 2 (Summer 1991), pp. 106–137. and Johnston, Ben and Gilmore, Bob (2006). "A Notation System for Extended Just Intonation" (2003), "Maximum clarity" and Other Writings on Music, p. 78. ISBN 978-0-252-03098-7

- ↑ Rudolf Rasch, "Tuning and Temperament", The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, Th. Christensen ed. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0 521 62371 5. p. 201.

- ↑ Smith, G. W., "Comma Sequences", Xenharmony, retrieved 2012-07-26.

- ↑ "Mercator-comma / Mercator's comma", Joe Monzo, tonalsoft.com