A compartmentalisation dam is a dam that divides a body of water into two parts. Such a dam is constructed, for instance, to regulate water levels separately in different sections of a basin. A notable application of a compartmentalisation dam is when it's built to enable closures with multiple tidal inlets, such as in the case of the Delta Works.[1]

Compartmentalisation Dam as a Watershed

When the quality of water in basins differs significantly and is undesirable, a separating dam is sometimes constructed. Examples include:

- Volkerakdam: built to prevent salt water from entering the freshwater Haringvliet, and to avoid polluted Rhine water from reaching the relatively clean Oosterschelde area.

- Houtribdijk: originally constructed as the northern dyke of the Markerwaard, but now serves to separate the basins of the Markermeer and IJsselmeer; the Houtribdijk also reduces the fetch during certain wind directions, reducing both wave growth and wind setup in the basin.

- Oesterdam: built to provide a tide-free waterway from Antwerp to Rotterdam and also to shrink the tidal basin of the Oosterschelde so the tidal difference at Yerseke and Zierikzee remained significant after the construction of the Oosterscheldekering.

Compartmentalisation Dams as Part of Closure Works in The Netherlands

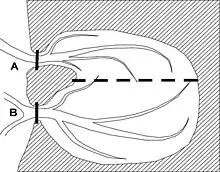

In tidal regions where a closure dam must be constructed and multiple sea connections exist, it's imperative to establish a compartmentalisation dam. Without such a dam (indicated by the dotted line), dam A would necessitate the entire basin to be filled via sea inlet B.[2][3] Such an action could drastically enhance the flow rate at this point, leading to the widening and deepening of the channel. This, in turn, could make it extremely challenging, if not outright impossible, to close the sea inlet.[4]

Erecting a compartmentalisation dam becomes relatively more straightforward when situated on a wantij. This Dutch term describes a shallow region or tidal divide within a deltaic system where two tidal currents converge. Because of these meeting tidal currents, the water effectively neutralises, leading to a spot or zone with barely any current, even if adjacent waters are moving rapidly.[5]

The wantij can be pivotal for navigation, posing potential difficulties for deeper-hulled ships or providing shelter from vigorous currents. The term is most frequently linked with the Dutch delta waters, especially those around the Zeeland province. In these regions, while the water level fluctuates with the tides, there's minimal flow velocity. As such, the construction of the dam becomes relatively straightforward. Examples of such compartmentalisation dams include three from the Delta Works in The Netherlands:[6]

- Volkerakdam: this dam separates the Haringvliet basin from the Volkerak.

- Grevelingendam: this dam separates the Oosterschelde basin from the Grevelingen.

- Zandkreekdam: this dam separates the Oosterschelde basin from the Veerse Gat.

The Dutch Deltacommissie (English: Delta Commission), a state committee of experts tasked with advising the government on the necessary measures to prevent a repeat of the 1953 flood disaster, referred to these structures not as compartmentalisation dams, but as side dams (Dutch: nevendammen).[7]

Upon the completion of these side dams, the original Delta Plan underwent modifications. Instead of constructing a dam at the Oosterschelde's mouth, a storm surge barrier known as the Oosterscheldekering was introduced. This alteration influenced the function of both dams. Initially, the intention behind the Oosterschelde dam was to create a vast freshwater basin, known as the Zeeland Lake. This basin would encompass the Oosterschelde, Krammer, Zijpe, and Volkerak, facilitating a tide-free waterway from Antwerp to Rotterdam. The route would incorporate a lock complex at the Volkerakdam and another at the Kreekrakdam.

Given that the Oosterschelde wasn't fully dammed (and the decision to erect a storm surge barrier there was postponed), the Volkerak continued to fill and drain through the tidal channel at Zijpe for an extended duration. This prolonged activity preserved a substantial flow rate within the Zijpe, causing notable erosion in this channel. As a result, supplementary protective measures were necessary at this location until the Oosterschelde Barrier was finalised.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Commission on Oosterschelde Compartmentalisation; Ferguson, H.A. (1975). Report on the Oosterschelde Compartmentalisation Committee. Rijkswaterstaat. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ↑ Maris, A.G.; De Blocq van Kuffeler, V.J.P.; Harmsen, W.J.H.; Jansen, P.P.; Nijhoff, G.P.; Thijsse, J.T.; Verloren van Themaat, R.; De vries, J.W.; Van der Wal, L.T. (1961). "Rapport Deltacommissie. Deel 1: Eindverslag en interimadviezen" [Report of The Delta Commission. Part 1: Final report and interim advice]. Deltacommissie (in Dutch). Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ↑ Huis in 't Veld, J. C.; Stuip, J.; Walther, A.W.; van Westen, J.M. (1987). The Closure of tidal basins: closing of estuaries, tidal inlets, and dike breaches (2nd ed.). Delft, the Netherlands: Delft University Press. ISBN 90-6275-287-X. OCLC 18039440. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ↑ Stamhuis, E. (1997). Afsluitingstechnieken in de Nederlandse Delta: Een overzicht van de ontwikkeling van deze techniek [Closure techniques in the Dutch Delta: An overview of the development of the technique] (in Dutch). The Hague: Rijkswaterstaat. ISBN 9057301768. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ↑ Watson, I.; Finkl, C. W. (1990). "State of the Art in Storm-Surge Protection: The Netherlands Delta Project". Journal of Coastal Research. 6 (3): 739–764. ISSN 0749-0208. JSTOR 4297737. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ↑ Maris, A.G. (1963). Delta Commission Report: Final Report and Interim Recommendations: Part I. State Publishing. pp. Pdf 003, p. 127 onwards. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ↑ van der Ham, W. (2003). Meester van de zee: Johan van Veen (1893 - 1959), waterstaatsingenieur [Master of the Sea: Johan van Veen (1893 - 1959), hydraulic engineer] (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Balans. ISBN 978-90-5018-595-0.

- ↑ "Rapport Deltacommissie (6 Parts. Part I: Final report and interim recommendations. Part II-IV: Considerations about storm surges and tidal movement. Part V: Investigations concerning the design of the Delta Plan and the consequences of the works. Part VI: Investigations of importance for the design of dikes and dams; socio-economic aspects of the Delta Plan.)" [Deltacommission Report] (in Dutch). Staatsdrukkerij- en Uitgeverijbedrijf. 1960–1961. Retrieved 24 September 2023 – via TU Delft repository.