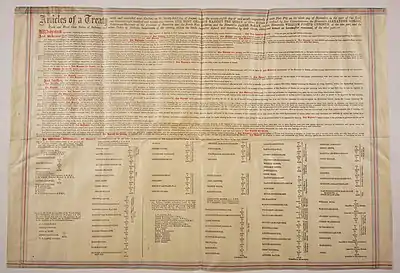

| Treaty No. 6 between Her Majesty the Queen and the Plain and Wood Cree Indians and Other Tribes of Indians at Fort Carlton, Fort Pitt, and Battle River with Adhesions | |

|---|---|

The Numbered Treaties | |

| Signed | 23 and 28 August and 9 September 1876 |

| Location | Fort Carlton, Fort Pitt |

| Parties | |

| Language | English |

| Indigenous peoples in Canada |

|---|

.JPG.webp) |

|

|

Treaty 6 is the sixth of the numbered treaties that were signed by the Canadian Crown and various First Nations between 1871 and 1877. It is one of a total of 11 numbered treaties signed between the Canadian Crown and First Nations. Specifically, Treaty 6 is an agreement between the Crown and the Plains and Woods Cree, Assiniboine, and other band governments at Fort Carlton and Fort Pitt. Key figures, representing the Crown, involved in the negotiations were Alexander Morris, Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories; James McKay, The Minister of Agriculture for Manitoba; and William J. Christie, a chief factor of the Hudson's Bay Company. Chief Mistawasis and Chief Ahtahkakoop represented the Carlton Cree.[1]

Treaty 6 included terms that had not been incorporated into Treaties 1 to 5, including a medicine chest at the house of the Indian agent on the reserve, protection from famine and pestilence, more agricultural implements, and on-reserve education. The area agreed upon by the Plains and Woods Cree represents most of the central area of the current provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta.

The treaty signings began on 18 August 1876 and ran until 9 September 1876. Additional adhesions, when bands within the Treaty area signed on, were signed later, including a Manitoba band in 1898, and, later that year, the last was signed in the Montreal Lake area.

Since Treaty 6 has been signed, there have been many claims over miscommunication of the treaty terms from the Indigenous and the Crown's perspective. This misunderstanding has led to disagreements between the Indigenous peoples and the government over the different interpretations of the treaty terms.[2]

Treaty 6 is still active today, and a Treaty 6 Recognition Day has been celebrated in Edmonton each August since 2013 to remember the signing in 1876.

Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations

In the spring of 1993, 17 Treaty 6 band governments in Alberta formed the Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations to be the "united political voice" of the Treaty 6 First Nations.[3] The confederacy does not contain any bands from outside of Alberta.

On 6 July 2012, the City of Edmonton, represented by Mayor Stephen Mandel, signed a partnership agreement with the Confederacy. This believed to be the first such agreement between a city in Alberta and a group of First Nations governments. Edmonton is within Treaty 6 territory and has the second-largest Indigenous population of any municipality in Canada.[4]

The Confederacy signed a protocol agreement with the Government of Alberta and the Alberta-Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations Relationship Agreement in July 2022 which provides for quarterly meetings with the minister of Indigenous relations and yearly meetings with the premier of Alberta.[5]

As of 2022 the Confederacy includes 16 member bands, including all bands party to Treaty 6 with reserves in Alberta but two (the exceptions being the Saddle Lake Cree and the Onion Lake Cree Nation).

Grand chiefs of the Confederacy

The grand chief is the primary spokesperson for the Confederacy in the media and represents the member nations in certain political fora.

Grand chiefs serve a one-year term roughly corresponding to the calendar year, and can be re-appointed. They are generally already serving as chief of one of the 17 member nations; however, Littlechild was an exception, as he was not the chief of his own band at the time he was grand chief.

- 2023: Leonard Standingontheroad (Chief of Montana First Nation)[6]

- 2022: George Arcand Jr. (Chief of Alexander First Nation)[7]

- 2021: (interim) Greg Desjarlais (Chief of Frog Lake First Nations)

- 2021: Vernon Watchmaker (Chief of Kehewin Cree Nation)

- 2020: William (Billy) Morin (Chief of Enoch Cree Nation)

Treaty 6 Flag. High Res File

Treaty 6 Flag. High Res File - 2017, 2018, 2019: Wilton Littlechild (not then sitting as a chief, but was a former member of parliament and commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada)

- 2016 (interim) Randy Ermineskin (Chief of Ermineskin Cree Nation)

- 2016 Tony Alexis (Chief of Alexis Nakota Sioux)

- 2015 Bernice Martial (Chief of Cold Lake First Nations, first woman grand chief)

- 2014 Craig Makinaw

- 2005 Eddy Makokis

Background

Treaty 6 was signed in August 1876 as an agreement between the Canadian Crown and the Plains and Woods Cree, Assiniboine, and other band governments at Fort Carlton and Fort Pitt. Signatories included Alexander Morris, Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories, James McKay, Manitoba's Minister of Agriculture, and W.J. Christie, Chief Factor of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). Chief Mistawasis and Chief Ahtahkakoop represented the Carlton Cree.[1] Colonel James Walker had also been instrumental in negotiating the treaty.[8]

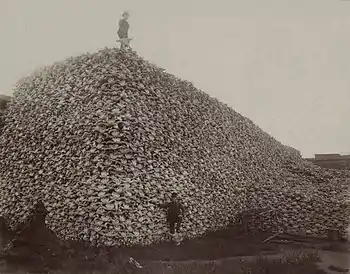

Prior to the near extinction of the American bison or buffalo in the late nineteenth century as waves of non-Indigenous immigrants arrived on the American frontier, traditional bison hunting was the way of life of the Plains Indians peoples, whose traditional lands spanned the North American great bison belt. Bison were the cultural symbol of these tribes—providing food, clothing and shelter. By 1871, the Indigenous peoples from the northern plains of the North-West Territories (NWT), the Cree, Ojibwa and Assiniboine, considered negotiating a treaty with the government to protect their traditional lands from settlers and HBC surveyors.[9] By the 1870s, the population of the once-plentiful bison had decreased to the point that tribal chiefs, elders, and many of the people sought the Crown's protection to ward off starvation.[9] They believed that a treaty with the government would guarantee assistance and prevent starvation.[9]

The fear of smallpox, which had spread to the northern plains tribes during the smallpox pandemic of 1870–1874, was another motivation for the chiefs to consider entering into a treaty with the Crown. The epidemic spread to the northern plains tribes, killing many of the Cree who had no immunity to this new disease. Because of emigration, smallpox had been introduced to America over the centuries. By 1873, thousands had caught the disease, hundreds, in eastern cities, such as Boston and New York and it had spread into Canada.[10] Previous smallpox epidemics brought by the emigrants to America included the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic that killed thousands of indigenous people along the Missouri River.[11][12]

Considering the sale of the NWT to Canada from the HBC, the Indigenous peoples were concerned about entering into a treaty with the Canadian government as they did not want their land to be taken over.[13] As treaties made their way slowly towards the North-West, the pressures of the Indigenous peoples on the government to make treaties increased. Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris proposed the government make a treaty in the west in 1872, but the suggestion was dismissed.[13] The Cree were told by traders each year that a treaty would be made with them soon to discuss their concerns, but years passed, and the government made no effort to create a treaty.[14] The government was uninterested in negotiating a treaty with the Indigenous peoples at the time, but as a result, the Cree stopped letting surveyors onto their territory and stopped telegraph workers from creating a line from Winnipeg to Fort Edmonton. The events eventually caught the attention of the government, which did not want a war with the Indigenous peoples. It wanted immigration to the North-West to continue, and a war would certainly halt settlement.[15] Thus began the negotiations for Treaty 6 at Fort Carlton.

Morris advised the government in 1872 to negotiate a treaty with the Indigenous peoples in the North-West. Many years later, he received authorization from the government to send the Reverend George McDougall to inform the Cree that a treaty would be negotiated at Fort Carlton and Fort Pitt during the summer of 1876. Morris was at Fort Garry and left on 27 July 1876 to make his way to Fort Carlton to negotiate a treaty with the Cree peoples. Morris was joined by W.J. Christie, Dr. Jackes, and was to meet James McKay at Fort Carlton. Morris and his team arrived at Fort Carlton on 15 August, and met with the chiefs of the Carlton Cree, Mistawasis and Ahtukukoop.[16] On 18 August, negotiations began after attempting to include the Duck Lake Indigenous peoples in the treaty.[17]

Terms

The government used the Robinson Treaties as an outline for Treaty 6 and all the numbered treaties. The Indigenous peoples involved in the Robinson Treaties were given money plus additional annual payments. Reserves were identified and indigenous people were given the right to hunt and fish on the land they used to own unless the land was sold or occupied. However, despite the Robinson Treaties serving as an outline, the Indigenous peoples of Treaty 6 negotiated additional terms into their treaty which the government did not intend to include.[9]

According to the settler version of history and the terms of treaty making, First Nations gave up their customary title to the land under common law in exchange for provisions from the government. The First Nations understanding is radically different from the British version; in the oral histories, translations (for example there is no concept of "land ownership" or "cede", which follows from the concept of land ownership, in the Cree language), and British customs, there continues to be controversy as to possible different understandings of the terms as they were used at the time of the treaty signings.

The Plain and Wood Cree Tribes of Indians, and all other the Indians inhabiting the district hereinafter described and defined, do hereby cede, release, surrender and yield up to the Government of the Dominion of Canada, for Her Majesty the Queen and Her successors forever, all their rights, titles and privileges, whatsoever, to the lands included within the following limits...[18]

During the treaty negotiations, the Indigenous peoples requested for agricultural tools, animals such as an ox and a cow for each family, assistance for the poor and those unable to work, the ban of alcohol in the province of Saskatchewan, and education to be provided for each reserve. In addition, the Indigenous peoples asked to be able to change the location of their settlement before the land was surveyed, ability to take resources from Crown lands such as timber, cooking stoves, medicine, a hand mill, access to bridges, and in the event of war the ability to refuse to serve.[19]

In exchange, for Indigenous lands, the federal government agreed to set up certain areas as "reserves" (i.e. protected from encroachment by white settlers). These lands no longer belong to the Indigenous peoples despite them living on it. The lands on which the Indigenous peoples lived, can be taken or sold by the government, but only with the consent of the natives peoples, or with compensation. In addition, the government promised to open schools for Indigenous children. Each reserve was to receive a school house, which would be built by the government. The idea of giving the Indigenous peoples an education was an attempt to help them become more successful in terms of communication with the settlers. It was also an attempt to help the Indigenous community understand how the Europeans lived, and to use their ways of living to help the Indigenous population thrive.[20] However, education was optional on reserves for the beginning of the treaty. The federal government offered education if the Indigenous peoples should desire it, but it was not mandatory. Nevertheless, not long after the treaty was signed, Indigenous children were being forced to attend school despite the treaty stating that it was optional for children to attend.[21] The sale of alcohol was also restricted on reserves.

The terms of Treaty 6 gave every family of five living on the reserve one square mile. Smaller families received land according to the size of their family. Each person immediately received CA$12 and an additional $5 a year. A maximum of four chiefs and other officers per band would receive $15 each and a salary of $25 per year plus one horse, one harness, and one wagon[22] or two carts. The Indigenous peoples also received a $1500 grant every year to spend on ammunition and twine in order to make fish nets. As well, each family was to be given an entire suite of agricultural tools including spades, harrows, scythes, whetstones, hay forks, reaping hooks, ploughs, axes, hoes, and several bags of seed. They were also to acquire a cross-cut saw, a hand saw, and a pit-saw, files, a grindstone, an auger, and a trunk of carpenter's tools. Additionally, they were to receive wheat, barley, potatoes, oats, as well as four oxen, a bull, six cows, two sows, and a hand-mill.[22] These were all included in Treaty 6 so that the Indigenous peoples would use these tools to create a living for themselves.

Pipe ceremony

_(20186418649).jpg.webp)

Religious practices are just as important to the Indigenous people as the serious discussions and decisions made. The pipe ceremony in the Indigenous community is something of sacred significance. It is associated with honour and pride and is conducted for both parties involved in an agreement to keep to their word. It is believed that the truth must only be told when the pipe is in attendance.[17] The smoking of the pipe was conducted at the negotiations of Treaty 6 to symbolize that this treaty would be honoured forever by both the Indigenous peoples and the Crown. It was also to indicate that anything said between the negotiators of the Crown and the Indigenous peoples would be honoured as well.[23] It was used at the beginning of the treaty negotiations as it was passed to Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris who rubbed it a few times before passing it to other members of the Crown present. This ceremony was to display that the negotiators of the Crown accepted the friendship of the Indigenous peoples, which signalled the start of the negotiations.[24] It is also the Indigenous way to signal the completion of an agreement between parties to guarantee each other's words. Due to the contrast of beliefs between the Indigenous and the Crown, the Crown did not see this ceremony as significant as the Indigenous people did. The negotiators of the Crown did not realize that this ceremony was of sacred importance to the Indigenous population which made their words and agreements mean much more to the Indigenous peoples than it did to the negotiators and the Crown. Spoken agreements to the Indigenous peoples have the same importance as written agreements do.[25]

Miscommunication

The Government of Canada believes the terms of the treaty were written down clearly within the document, but in the oral traditions of the Indigenous peoples, they have a different understanding of the treaty terms.[25] Although there were three interpreters presents at the negotiations for Treaty 6, two from the Crown and one from the Indigenous peoples, direct translation of words between English and Cree was not possible. Certain words in either language did not have a corresponding word in the opposite language. This meant that both groups did not understand each other fully as the concepts were changed due to the word changes between the languages. The Indigenous peoples had to especially rely on their interpreter because the document they were to sign was solely in English, giving them the disadvantage as the interpreter had to explain the words, meanings and concepts of the treaty text because the Cree could not speak or read English.[26] The Indigenous peoples claim they accepted Treaty 6 because they were informed that the Crown did not want to buy their land, but instead borrow it.[27] Another understanding was that the Indigenous peoples could choose the amount of land they wanted to retain, but surveyors came to set per person perimeters on the reserves which was seen as a violation of the treaty.[2] Indigenous peoples thought the treaty would adapt due to the changing conditions such as the amount of currency, the drastic change in health services, and the more efficient agricultural tools which have been invented or modified to better suit the conditions of farming. However, the treaty terms have remained the same which have caused Indigenous peoples to believe the treaty terms should be re-evaluated to better suit the needs of Indigenous people today.[28]

Alexander Morris emphasized that the Queen had sent him as she wanted peace within Canada, and for all her children to be happy and well taken care of.[29] The Indigenous peoples were affected by this statement as women in their culture are seen as having a more important role than men. This belief is implemented into Indigenous people's political roles which is the reason why women do not negotiate as the land is seen as the women's, therefore if women do not negotiate then the land can never fully be surrendered.[30] The reoccurring image of the Queen and her children was a main reason for the Indigenous peoples to sign Treaty 6. They believed the Queen, as a woman, was not taking away their land but only sharing it. The phrase "for as long as the sun shines and the waters flow" was used in ensuring that this treaty would last forever. The Crown interpreted the water to be the rivers and lakes, however the Indigenous peoples saw the water to mean the birth of a child and as long as children were being born then the treaty would remain.[20]

Medicine Chest Clause

One of the selling points of the treaty was that a medicine chest would be kept at the home of the Indian agent for use by the people. Another of the selling points was the guarantee of assistance for famine or pestilence relief.

The "medicine chest clause" has been interpreted by native leaders to mean that the federal government has an obligation to provide all forms of healthcare to First Nations people on an ongoing basis. In particular, the Assembly of First Nations considers the funding of the Non-Insured Health Benefits program as one aspect of this responsibility.[31]

At the time Treaty 6 was signed, the famous medicine chest clause was inserted at Indian insistence that the Indian agent should keep a medicine chest at his house for use. Today Indian thinking is this means medical care, in general terms, the medicine chest may be all they had at that time and place but today we have a broader range of medical care and this is a symbol for that.

— Historian John Taylor[32]

The interpretation of that clause is very different for the federal government employees or bureaucrats and the Indian leadership because to us and to our elders and leaders who negotiated and signed that treaty, it refers to health care and health benefits for our people. And because our traditional way of healing is still present and alive but we recognized that we would need that assistance.

List of Treaty 6 First Nations

- Alberta

- Alexander First Nation

- Alexis First Nation

- Beaver Lake Cree Nation

- Cold Lake First Nation

- Enoch Cree Nation

- Ermineskin Cree Nation

- Frog Lake First Nation

- Heart Lake First Nation

- Kehewin Cree Nation

- Louis Bull Tribe

- Michel First Nation

- Montana First Nation

- O'Chiese First Nation

- Papaschase

- Paul First Nation

- Saddle Lake Cree Nation

- Samson First Nation

- Sunchild First Nation

- Manitoba

- Saskatchewan

- Ahtahkakoop First Nation

- Beardy's and Okemasis First Nation

- Big Island Lake Cree Nation

- Big River First Nation

- Flying Dust First Nation

- James Smith First Nation

- Lac La Ronge First Nation

- Little Pine First Nation

- Lucky Man First Nation

- Makwa Sahgaiehcan First Nation

- Ministikwan Lake Cree Nation

- Mistawasis First Nation

- Montreal Lake Cree Nation

- Moosomin First Nation

- Mosquito-Grizzly Bear's Head-Lean Man

- Muskeg Lake Cree Nation

- Muskoday First Nation

- One Arrow First Nation

- Onion Lake Cree Nation

- Pelican Lake First Nation

- Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation

- Poundmaker Cree Nation

- Red Pheasant First Nation

- Saulteaux First Nation

- Sweetgrass First Nation

- Sturgeon Lake First Nation

- Thunderchild First Nation

- Waterhen Lake First Nation

- Witchekan Lake First Nation

Timeline

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 23 August 1876 | First signing at Fort Carlton |

| 28 August 1876 | Second signing at Fort Carlton |

| 9 September 1876 | Fort Pitt signing |

| 9 August 1877 | Fort Pitt adhesion signing by Cree bands |

| 21 August 1877 | Fort Edmonton signing |

| 25 September 1877 | Blackfoot Crossing at Bow River signing (at Siksika Nation reserve, Alberta) |

| 19 August 1878 | Additional signing |

| 29 August 1878 | Battleford signing |

| 3 September 1878 | Carlton signing |

| 18 September 1878 | Additional signing, Michel Calihoo Band, 25,600 acres (104 km2) near Edmonton, Alberta[33] |

| 2 July 1879 | Fort Walsh signing |

| 8 December 1882 | Further Fort Walsh signing |

| 11 February 1889 | Montreal Lake signing |

| 10 August 1898 | Colomb band signing in Manitoba |

| 25 May 1944 | Rocky Mountain House adhesion signing |

| 13 May 1950 | Further Rocky Mountain House adhesion signing |

| 21 November 1950 | Witchekan Lake signing |

| 18 August 1954 | Cochin signing |

| 15 May 1956 | Further Cochin signing |

| 1958 | Members of the Michel Band are enfranchised by the Department of Indian Affairs. They were made into Canadian citizens but lost Treaty status, and the reserve was dissolved. This is the only case of an entire band (save a few individuals) being involuntarily enfranchised.[34] |

See also

References

- 1 2 Chalmers (1977), p. 23.

- 1 2 Asch (1997), p. 197.

- ↑ "Treaty 6 - Home". Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ "Historic Agreement Between the Confederacy of Treaty No. 6 First Nations and City of Edmonton :: City of Edmonton". Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ "Confederacy signs relationship agreement with Alberta". 19 July 2022.

- ↑ "Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations names new grand chief - Edmonton | Globalnews.ca".

- ↑ "New grand chief wants action taken on agreements signed with Alberta, Edmonton".

- ↑ "Col. James Walker".

- 1 2 3 4 Taylor (1985), p. 4.

- ↑ Rolleston, J. D. (1 December 1933). "The Smallpox Pandemic of 1870–1874". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. President's Address. 27 (2): 177–192. doi:10.1177/003591573302700245. ISSN 0035-9157.

- ↑ Rationalizing Epidemics: Meanings and Uses of American Indian Mortality Since 1600; David S. Jones; Harvard University Press; 2004; Pg. 76

- ↑ The Effect of Smallpox on the Destiny of the Amerindian; Esther Wagner Stearn, Allen Edwin Stearn; University of Minnesota; 1945; Pgs. 13-20, 73-94, 97

- 1 2 Taylor (1985), p. 5.

- ↑ Taylor (1985).

- ↑ Taylor (1985), p. 3.

- ↑ Taylor (1985), p. 9.

- 1 2 Taylor (1985), p. 10.

- ↑ Duhame, Roger (1964). "Copy of Treaty No. 6 between Her Majesty the Queen and the Plain and Wood Cree Indians and other Tribes of Indians at Fort Carlton, Fort Pitt and Battle River with Adhesions". Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. IAND Publication No. QS-0574-000-EE-A-1.

- ↑ Taylor (1985), p. 17.

- 1 2 Asch (1997), p. 194.

- ↑ Chalmers (1977), p. 26.

- 1 2 Chalmers (1977), p. 25.

- ↑ Asch (1997), p. 188.

- ↑ Chalmers (1977), p. 24.

- 1 2 Wing (2016), p. 204.

- ↑ Whitehouse-Strong, Derek (Winter 2007). "'Everything Promised Had Been Included in the Writing' Indian Reserve Farming and the Spirit and Intent of Treaty Six Reconsidered". Great Plains Quarterly. Center for Great Plains Studies, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 27 (1): 30.

- ↑ Wing (2016), p. 206.

- ↑ Chalmers (1977), p. 27.

- ↑ Asch (1997), p. 190.

- ↑ Asch (1997), p. 191.

- ↑ "NIHB". Program Areas. Assembly of First Nations. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- 1 2 "Cede, Yield and Surrender: A History of Indian Treaties in Canada". Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. 15 September 2010. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012.

- ↑ K. Dalheim (1955). Calahoo Trails: A History of Calahoo, Granger, Speldhurst-Noyes Crossing, East Bilby, Green Willow, 1842-1955. Women's Institute (Canada). Calahoo Women's Institute. p. 14.

- ↑ Friends of the Michel Society 1958 Enfranchisement Claim

- Sources

- Asch, Michael (1997). Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equity, and Respect for Difference. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0581-0.

- Chalmers, John W. (Spring 1977). "Treaty No. Six". Alberta History. 25 (2): 23–27.

- Taylor, John Leonard (1985). Treaty Research Report Treaty Six (1876) (PDF) (Report). Treaties and Historical Research Centre Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

- Wing, Miriam Lily (November 2016). "Divisions in Treaty 6 Perspectives: The Dilemma of Written Text and Oral Tradition". MUSe3. 3 (1): 200–210.

External links

- The Making of Treaty 6 - Alberta Online Encyclopedia

- Treaty Texts: Treaty No. 6 from the Government of Canada

- Confederacy of Treaty 6 First Nations