| Crepidotus praecipuus | |

|---|---|

| |

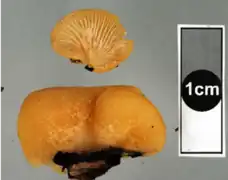

| Crepidotus praecipuus growing on rotten beech (Nothofagus) log from the South Island of New Zealand. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Agaricales |

| Family: | Crepidotaceae |

| Genus: | Crepidotus |

| Species: | C. praecipuus |

| Binomial name | |

| Crepidotus praecipuus | |

| Crepidotus praecipuus | |

|---|---|

| Gills on hymenium | |

| Cap is convex | |

| Hymenium is free | |

| Lacks a stipe | |

| Spore print is yellow-brown | |

| Ecology is saprotrophic | |

| Edibility is unknown | |

Crepidotus praecipuus, is a species of fungus in the family Crepidotaceae first described in 2018.[1] It is commonly known as a rusty-gilled conch, along with other kidney shaped, rusty-brown spored species of Crepidotus. It is saprobic on wood, like other Crepidotus species.

Description

- Cap: The cap (pileus) of C. praecipuus is generally about 1–7 cm in diameter and is convex in shape with an even margin that curls inwards.[2] The cap can range from flabelliform to semicircular, to kidney-shaped depending on the surface from which they grow. If they grow on a vertical surface, they are more likely to form a typical shelf-like structure, appearing in the commonly described ‘kidney’ shape while visually remaining semicircular from above. This shape is different if they protrude from underneath their substrate material, usually a log, appearing instead more circular and as if the point of attachment is directly on top of the cap surface.[3] The cap surface is covered in fibrillose scales that range yellowish-brown to brown in colour. To one side the cap has a tomentellous (finely felted) surface. This scaly side is where the stipeless cap laterally attaches to substrate.[4]

- Gills: On the underside, the gills (lamellae) appear somewhat fringed and are classified as free (see description box) with no stipe to connect to.[4] The colour of the gills depends on the maturity of the spores ranging from off-white when young to yellow-brown/rusty-brown as the spores mature.

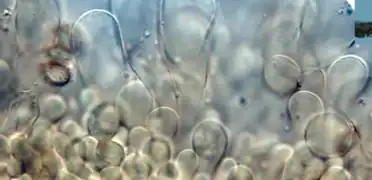

- Spores: The spore print is yellow-brown,[2] reflecting the colour of the gills. The ellipsoid-shaped basidiospore of C. praecipuus are 6.3-7.8 by 5.1-6.6 µm in size and are described as having smooth exteriors to their thick walls.[2] The top of the basidiospore (apex) can be blunt, depressed or periodically pointed.[4][2] (See figure 2.)

- Basidium: The basidia of C. praecipuus is 26-65 by 4-14 μm in size, club-shaped, cylindrical with four spores attached to the top of each basidium top.[2]

- Basidiomata: C. praecipuus can have a basidiomata that is relatively larger than other species (see similar species), ranging from 1 –7 cm in length. Being a defining characteristic, it helps set C. praecipuus apart from other species.[2]

- Absent features- No stipe (stem)[2] or annulus (ring).

Distribution

C. praecipuus has been recorded in 3 countries as of 2022: New Zealand, Australia, and South Korea.

In New Zealand, Landcare Research has declared the species as indigenous but non-endemic because C. praecipuus is also present in Australia.[5]

In 2021, the Ministry of Environment of South Korea reported this species was found on the island of Daecheongdo which is 210 km northwest from land in the Yellow Sea. This island was completely cleared through bombing in the Korean War in 1950. Because there has been no artificial reforestation since the 1970s, all that is currently there has been naturally established.[2]

Habitat

In the southern hemisphere C. praecipuus is generally found in southern beech forests on dead woody material. The forests in which C. praecipuus is found in Korea are primarily made up of Carpinus turczaninoxii, Camellia japonica and Quercus sp. with a high distribution of pine trees (Pinus densiflora) throughout these forests. However, in these sorts of forests in Korea, C. praecipuus has only been found on dead deciduous branches.[2]

Ecology

Despite being found on woody material, C. praecipuus is not parasitic as the spores only establish themselves on dead material, not when the organism is alive. Saprotrophic fungi like C. praecipuus are important to their habitat because they can decompose organic material into different molecules that can be reused by other organisms while also clearing space for them.[6]

Life cycle

Fruiting season: Autumn (May in New Zealand, September in Korea[2]) and on occasion after spells of warm rains.[3]

The mushroom part of the fungus, the part that is most often used to identify the organism, is only the fruiting body. Fruiting occurs only at certain times per year to disperse basidiospores; otherwise the majority of the organism remains generally out of sight within its substrate.[6]

The initial release of spores is triggered with various climatic fluctuations such as water drops hitting the cap, shaking the spores from their basidium, mist triggering the detachment and wind picking up spores off the gills. The spores can then travel at high altitudes over vast distances including entire oceans. The distance the spore travels in total usually depends on mass of the spore and the velocity of travel. The travel ends the same way it begins: with a steady rain clearing the atmosphere of most suspended particles.[6]

Once the spore lands on an adequate substrate it germinates through its apex in the presence of water and continues to grow outwards in all directions through the substrate. The hypha behind the tip is continuously dying due to nutrition only being obtained from the tip. Once the hypha finds another mycelium of the same species it fuses with it and creates a mushroom body in its fruiting season.[6]

Taxonomy

C. praecipuus is closely related to C. tobolensis, C. macedonicus and C. lutescens; these species sometimes are mistaken for each other.[2] Less closely related is the North American C. croceitinctus and the European C. cesatii.[7] C. praecipuus has no subspecies and it can be told apart from other species by appearance.[2]

Similar species and genera

- Crepidotus tobolensis : Although C. tobolensis can look almost identical to C. praecipuus with its brightly pigmented cap, the major differences are visible under a microscope. C. tobolensis has a smaller basidiomata length at 0.7-4.3 cm long; however, C. tobolensis produces on average 22% more spores than C. praecipuus.[2] C. tobolensis also differs in distribution to C. praecipuus appearing in the Tyumen Region of Russia.[7]

- Crepidotus macedonicus : C. macedonicus has a more muted cap colour yet its main difference from C. praecipuus is in its spore characteristics. C. macedonicus has a spore quantity similar to that of C. tobolensis, in addition to a more elongated shape that sets it apart from not only C. praecipuus but also C. lutescens.[7]

- Crepidotus lutescens : C. lutescens is a Chinese species of this genus that primarily differentiates itself from C. praecipuus by its basidiomata size as its spore shape can resemble that of C. praecipuus.[7]

- Conchomyces bursaeformis (common name Ivory conch): Similar in size, the white spore print is a clear indicator as its heavily reduced but present (0.1 cm in length) stipe can make it difficult to identify what genus and species it is.[3]

Gallery

Fig. 1 Specimen collected in June (NZ)

Fig. 1 Specimen collected in June (NZ) Fig. 2 Spores.

Fig. 2 Spores. Fig. 3 Microscopic views. top left: section through surface. Bottom left: subcutis. Right: terminal elements.

Fig. 3 Microscopic views. top left: section through surface. Bottom left: subcutis. Right: terminal elements. Fig. 4 Cheilocystidia

Fig. 4 Cheilocystidia

References

- 1 2 Horak, Egon (2018). Samson, R.A. (ed.). Fungi of New Zealand, Volume 6: Agaricales of New Zealand 2 Brown Spored Genera. Westerdijk Biodiversity Series. Utrecht, Netherlands: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures. p. 205. ISBN 9789491751134.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Kim, Minkyeong; Lee, Jin Sung; Park, Jae Young; Kim, Changmu (2021). "First Report Six Macrofungi from Daecheongdo and Socheongdo Island, Korea". Mycobiology. 49 (5). doi:10.1080/12298093.2021.1970957. PMC 8583917.

- 1 2 3 Ridley, Geoff S. (2006). A Photographic Guide to Mushrooms and Other Fungi of New Zealand. New Holland Publishers (NZ) Ltd. ISBN 9781869661342.

- 1 2 3 Cooper, J. A. "Crepidotus praecipuus". New Zealand's Virtual Mycota. Landcare Research. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Crepidotus praecipuus E. Horak 2018". Biota of New Zealand. Landcare Research. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Deacon, J. (2006). Fungal Biology (Fourth ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9781405130660.

- 1 2 3 4 Kapitonov, Vladimir I.; Biketova, Alona Yu.; Zmitrovich, Ivan V. (2009). "Fungal Planet description sheets: 868–950" (pdf). Persoonia - Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. Naturalis Biodiversity Center/ Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute. 42. doi:10.3767/persoonia.2019.42.11. ISSN 1878-9080. Retrieved June 15, 2022.