| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Malta |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology and Folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

The culture of Malta has been influenced by various societies that have come into contact with the Maltese Islands throughout the centuries, including neighbouring Mediterranean cultures, and the cultures of the nations that ruled Malta for long periods of time prior to its independence in 1964.

History

The culture of prehistoric Malta

The earliest inhabitants of the Maltese Islands are believed to have been Sicani from nearby Sicily who arrived on the island sometime before 5000 BC. They grew cereals and raised domestic livestock and, in keeping with many other ancient Mediterranean cultures, formed a fertility cult represented in Malta by statuettes of unusually large proportions. Pottery from the earliest period of Maltese civilization (known as the Għar Dalam phase) is similar to examples found in Agrigento, Sicily. These people were either supplanted by, or gave rise to a culture of megalithic temple builders, whose surviving monuments on Malta and Gozo are considered the oldest standing stone structures in the world.[1][2][3] The temples date from 4000 to 2500 BC and typically consist of a complex trefoil design.

Little is known about the temple builders of Malta and Gozo; however there is some evidence that their rituals included animal sacrifice. This culture disappeared from the Maltese Islands around 2500 BC and was replaced by a new influx of Bronze Age immigrants, a culture that is known to have cremated its dead and introduced smaller megalithic structures called dolmens to Malta,[4] probably imported by Sicilian population because of the similarity of Maltese dolmens with similar constructions found in the largest island of the Mediterranean sea.[5]

The development of modern Maltese culture

The culture of modern Malta has been described as a "rich pattern of traditions, beliefs and practices," which is the result of "a long process of adaptation, assimilation and cross fertilization of beliefs and usages drawn from various conflicting sources." It has been subjected to the same complex, historic processes that gave rise to the linguistic and ethnic admixture that defines who the people of Malta and Gozo are today.[6]

Present-day Maltese culture is essentially Latin European with the recent British legacy also in evidence. In the early part of its history, Malta was also exposed to Semitic-speaking communities. The present-day legacy of this is linguistic rather than cultural. The Latin European element is the major source of Maltese culture because of the virtually continuous cultural impact on Malta over the past eight centuries and the fact that Malta shares the religious beliefs, traditions and ceremonies of its Sicilian and Southern European neighbors.

Sources of Semitic influence

Phoenicians

The Phoenicians inhabited the Maltese Islands from around 700 BCE,[7] and made extensive use of their sheltered harbours. By 480 BCE, with the ascendancy of Carthage in the western Mediterranean, Malta became a Punic colony. Phoenician origins have been suggested for the Maltese people and their customs since 1565. A genetic study carried out by geneticists Spencer Wells and Pierre Zalloua of the American University of Beirut argued that more than 50% of Y-chromosomes from Maltese men may have Phoenician origins.[8] However, it is noted that this study is not peer reviewed and is contradicted by major peer reviewed studies, which prove that the Maltese share common ancestry with Southern Italians, having negligible genetic input from the Eastern Mediterranean or North Africa.[9][10]

Algerian legend claims that the ancestors of the present Maltese, together with the first Algerians, fled from their original homeland of Aram, with some choosing to settle in Malta and others in North Africa, which would suggest that the prototypical Maltese culture had Aramaean origins.[11] Another tradition suggests that the Maltese are descended from shepherd tribes who fled Bethlehem in the face of an advancing enemy, set sail from Jaffa, and settled in Malta.[12] There is also some evidence that at least one North African tribe, the Oulad Said, claim that they share common ancestry with the Maltese.[13]

Aghlabid conquest

This period coincided with the golden age of Moorish culture and included innovations like the introduction of crop rotation and irrigation systems in Malta and Sicily, and the cultivation of citrus fruits and mulberries. Then capital city Mdina, originally called Maleth by the Phoenicians, was at this time refortified, surrounded with a wide moat and separated from its nearest town, Rabat. This period of Arabic influence[14] followed the conquest of Malta, Sicily and Southern Italy by the Aghlabids. It is presently evident in the names of various Maltese towns and villages and in the Maltese language, a genetic descendant of Siculo-Arabic. It is noted that, during this period, Malta was administered from Palermo, Sicily, as part of the Emirate of Sicily. Genetic studies indicate that the Arabs who colonised Malta in this period were in fact Arabic-speaking Sicilians.,[9][10]

It is difficult to trace a continuous line of cultural development during this time. A proposed theory that the islands were sparsely populated during Fatimid rule is based on a citation in the French translation of the Rawd al-mi'ṭār fī khabar al-aqṭār ("The Scented Garden of Information about Places").[15] Al-Himyari describes Malta as generally uninhabited and visited by Arabs solely for the purpose of gathering honey and timber and catching fish. No other chronicles make similar descriptions and this claim is not universally accepted.

Up to two hundred years after Count Roger the Norman conquered the island, differences in the customs and usages of the inhabitants of Malta were distinct from those in other parts of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies: moribus d'aliis de vivunt d'ipsarum d'insularum de homines et constitutionibus, nostri Sicilie.[17]

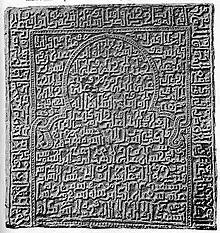

The marble gravestone of a Saracen girl named Majmuna (pr. My-moona), found in a pagan temple in the Xewkija area of Gozo dates back to 1173.[16] Written in Kufic, it concludes saying, "You who read this, see that dust covers my eyelids, in my place and in my house, nothing but sadness and weeping; what will my resurrection be like?"

The population of Malta at that time amounted to no more than 1,119 households, of whom 836 were described as Saracens, inhabiting the island following the Norman invasion and before their ultimate expulsion.

Jewish presence

A number of Jewish families resided in Malta almost consistently from approximately 1500 BCE to the 1492 Edict of Expulsion, and again from the time of the Knights of Malta through to the present. This is yet another source of Semitic influence in Maltese culture.

According to local legend,[18] the earliest Jewish residents arrived in Malta some 3,500 years ago, when the seafaring tribes of Zebulon and Asher accompanied the ancient Phoenicians in their voyages across the Mediterranean. The earliest evidence of a Jewish presence on Malta is an inscription in the inner apse of the southern temple of Ġgantija (3600–2500 BC)[19] in Xagħra, which says, in the Phoenician alphabet: "To the love of our Father Jahwe". There is evidence of a Jewish community on Malta during the Roman period, in the form of carved menorahs the catacombs in Malta. Members of the Malta's Jewish community are known to have risen to the highest ranks of the civil service during the period of Arab occupation, including the rank of Vizier. By 1240, according to a report prepared for Emperor Frederick II, there were 47 Christian and 25 Jewish families on Malta, and 200 Christian and 8 Jewish families on Gozo.

Unlike the Jewish experience in the rest of Europe, throughout the Middle Ages the Jews of Malta generally resided among the general population rather than in ghettos, frequently becoming landowners. The Jewish population of Malta had flourished throughout the period of Norman rule, such that one third of the population of Malta's ancient capital, Mdina, is said to have been Jewish.[20]

In 1492, in response to the Alhambra Decree the Royal Council had argued – unsuccessfully – that the expulsion of the Jews would radically reduce the total population of the Maltese Islands, and that Malta should therefore be treated as a special case within the Spanish Empire.[21] Nonetheless, the decree of expulsion was signed in Palermo on 18 June 1492, giving the Jewish population of Malta and Sicily three months to leave. Numerous forced conversions to Catholicism, or exile, followed. Evidence of these conversions can be found in many Maltese family names that still survive today, such as the families Abela, Ellul, Salamone, Mamo, Cohen, and Azzopardi.[22]

A much smaller Jewish community developed under the rule of the Knights of Malta, but this consisted primarily of slaves and emancipated slaves. Under the rule of certain Grandmasters of the Order, the Jews were made to reside in Valletta's prisons at night, while by day they remained free to transact business, trade and commerce among the general population.

Local place names around the island, such as Bir Meyru (Meyer's Well), Ġnien il-Lhud (The Jew's Garden) and Ħal Muxi (Moshé's Farm)[21] attest to the endurance of Jewish presence in Malta.

Slaves in Malta

Exposure to Semitic influences continued to a limited extent during the 268-year rule of the Knights of St. John over Malta, due in part to trade between the Knights and North Africa, but primarily due to the large numbers of slaves present in Malta during the 17th and 18th centuries: upwards of 2,000 at any given time (or about 5 per cent of the population of Malta), of whom 40–45 per cent were Moors, and the remainder Turks, Africans and Jews. There were so many Jewish slaves in Malta during this time that Malta was frequently mentioned for its large enslaved Jewish population in Jewish literature of the period.[23]

The slaves were engaged in various activities, including construction, shipbuilding and the transportation of Knights and nobles by sedan-chair. They were occasionally permitted to engage in their own trades for their own account, including hairdressing, shoe-making and woodcarving, which would have brought them into close contact with the Maltese urban population. Inquisitor Federico Borromeo (iuniore) reported in 1653 that:

[slaves] strolled along the street of Valletta under the pretext of selling merchandise, spreading among the women and simple-minded persons any kind of superstition, charms, love-remedies and other similar vanities.[24]

A significant number of slaves converted to Christianity, were emancipated, or even adopted by their Maltese patrons which may have further exposed Maltese culture to their customs.[25]

Sources of Latin European influence

Roman municipium

From 218 BCE to 395 CE, Malta was under Roman political control, initially as a praetorship of Sicily. The islands were eventually elevated to the status of Roman municipium, with the power to control domestic affairs, mint their own money, and send ambassadors to Rome. It was during this period that St. Paul was shipwrecked on the Maltese Islands and introduced Christianity. Few archeological relics survive in Malta today from the Roman period, the sole exception being the Roman Domus, just outside the walls of Mdina. From a cultural perspective, the Roman period is notable for the arrival in Malta of several highly placed Roman families, whose progeny form part of the Maltese nation today. These include the Testaferrata family (originally, "Capo di Ferro"), today one of Malta's premier noble families.

Whether the origins of Maltese culture can be found in the Eastern Mediterranean or North Africa, the impact on Malta of Punic culture is believed to have persisted long after the Island's incorporation into the Roman Republic in 218 BCE:

... at least during the first few centuries of Roman rule, tradition, customs and language were still Punic despite romanization of the place. This is in agreement with what can be read in the Acts of the Apostles, which call the Maltese "barbarians", that is using a language that was neither Greek nor Latin, but Punic.[26]

With the division of the Roman Empire, in 395 CE, Malta was given to the eastern portion ruled from Constantinople and this new colonization introduced Greek families to the Maltese collective,[27] bringing with them various superstitions, proverbs, and traditions that exist within Maltese culture today.[28]

Catholicism

It is said that in Malta, Gozo, and Comino there are more than 365 churches, or one church for every 1,000 residents. The parish church (Maltese: "il-parroċċa", or "il-knisja parrokjali") is the architectural and geographic focal point of every Maltese town and village, and its main source of civic pride. This civic pride manifests itself in spectacular fashion during the local village festas, which mark the feast day of the patron saint of each parish with marching bands, religious processions, special Masses, fireworks (especially petards), and other festivities.

Making allowances for a possible break in the appointment of bishops to Malta during the period of the Fatimid conquest, the Maltese Church is referred to today as the only extant Apostolic See other than Rome itself. According to tradition and as recorded in the Acts of the Apostles, the Church in Malta was founded by St. Paul in AD 70, following his shipwreck on these Islands. The earliest Christian place of worship in Malta is said to be the cavern in Rabat Malta, now known as St. Paul's Grotto, where the apostle was imprisoned during his stay on Malta. There is evidence of Christian burials and rituals having taken place in the general vicinity of the Grotto, dating back to the 3rd century AD.

Further evidence of Christian practices and beliefs during the period of Roman persecution can be found in the many catacombs that lie beneath various parts of Malta, including St Paul's Catacombs and St Agatha's Catacombs in Rabat, just outside the walls of Mdina. The latter, in particular, were beautifully frescoed between 1200 and 1480; they were defaced by marauding Turks in the 1550s. There are also a number of cave churches, including the grotto at Mellieħa, which is a Shrine of the Nativity of Our Lady where, according to legend, St. Luke painted a picture of the Madonna. It has been a place of pilgrimage since medieval times.

The writings of classic Maltese historian, Gian. Francesco Abela recount the conversion to Christianity of the Maltese population at the hand of St. Paul.[29] It is suggested that Abela's writings were used by Knights of Malta to demonstrate that Malta had been ordained by God as a "bulwark of Christian, European civilization against the spread of Mediterranean Islam."[30] The native Christian community that welcomed Roger I of Sicily[31] was further bolstered by immigration to Malta from Italy, in the 12th and 13th centuries.

For centuries, leadership over the Church in Malta was generally provided by the Diocese of Palermo, except under Charles of Anjou who caused Maltese bishops to be appointed, as did – on rare occasions – the Spanish and later, the Knights. This continued Malta's connections with Sicily and Italy, and contributed to, from the 15th century to the early 20th century, the dominance of Italian as Malta's primary language of culture and learning. Since 1808 all bishops of Malta have been Maltese.

During the Norman and Spanish periods and under the rule of the Knights, Malta became the devout Catholic nation it is today. It is worth noting that the Maltese Inquisition (more properly called the Roman Inquisition)[32] had a very long tenure in Malta following its establishment by the Pope in 1530; the last Inquisitor departed from the Islands in 1798, after the Knights capitulated to the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Normans

The later years of Norman rule over Malta brought massive waves of immigration to the Islands from Sicily and from the Italian mainland, including clergy and notaries. Sicilian became the sole written language of Malta, as evidenced by notarial deeds from this period, but this was eventually supplanted by Tuscan Italian, which became the primary literary language and the medium of legal and commercial transactions in Malta. A large number of Sicilian and Italian words were adopted into the local vernacular.

Traces of Siculo-Norman architecture can still be found in Malta's ancient capital of Mdina and in Vittoriosa, most notably in the Palaces of the Santa Sofia, Gatto Murina, Inguanez and Falzon families.[33]

Spain

Traces of the ascendancy of the Crown of Aragon in the Mediterranean, and Spanish governance over Malta from 1282 to 1530, are still evident in Maltese culture today. These include culinary, religious, and musical influences. Two examples are the enduring importance of the Spanish guitar (Maltese: il-kitarra Spanjola) in Maltese folk music, and the enclosed wooden balconies (Maltese: gallerija) that grace traditional Maltese homes today. It is also possible that the traditional Maltese costume, the Faldetta, is a local variation of the Spanish mantilla.

The Spanish period also saw the establishment of local nobility, with the creation of Malta's oldest extant title, the Barony of Djar-il-Bniet e Buqana, and numerous others. Under Spanish rule Malta developed into a feudal state. From time to time during this period, the Islands were nominally ruled by various Counts of Malta, who were typically illegitimate sons of the reigning Aragonese monarch; however, the day-to-day administration of the country was essentially in the hands of the local nobility, through their governing council known as the Università.

Some of Malta's premier noble families including the Inguanez family, settled in Malta from Spain and Sicily during this time. Other Maltese families of Spanish origin include: Alagona, Aragona, Abela, Flores, Guzman and Xerri.

The period of Spanish rule over Malta lasted roughly as long as the period of Arab rule; however, this appears to have had little impact on the language spoken in rural Malta, which remained heavily influenced by Arabic, with Semitic morphemes. This is evident in Pietro Caxaro's Il-Kantilena, the oldest known literary text in Maltese, which was written prior to 1485, at the height of the Spanish period.

The Knights of St. John

The population of Malta increased considerably during the rule of the Knights, from 25,000 in 1535 to over 40,000 in 1621, to over 54,463 in 1632. This was primarily due to immigration from Western Europe, but also due to generally improved health and welfare conditions, and the reduced incidence of raids from North African and Turkish corsairs. By 1798, when the Knights surrendered Malta to the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte, the population of Malta had increased to 114,000.

The period of the Knights is often referred to as Malta's Golden Age, as a result of the architectural and artistic embellishment of the Islands by their resident rulers, and as a result of advances in the overall health, education and prosperity of the local population during this period. Music, literature, theatre and the visual arts all flourished in Malta during this period, which also saw the foundation and development of many of the Renaissance and Baroque towns and villages, palaces and gardens of Malta, the most notable of which is the capital city, Valletta.

Contact between the Maltese and the many Sicilian and Italian mariners and traders who called at Valletta's busy Grand Harbour expanded under Knights, while at the same time, a significant number of Western European nobles, clerics and civil servants relocated to Malta during this period. The wealth and influence of Malta's noble families – many of whom trace their ancestry back to the Norman and Spanish monarchs who ruled Malta prior to the Knights – was also greatly enhanced during this period.

Maltese education, in particular, took a significant leap forward under the Knights, with the foundation, in 1592, of the Collegium Melitense, precursor to today's University of Malta, through the intercession of Pope Clement VIII. As a result, the University of Malta is one of the oldest extant universities in Europe, and the oldest Commonwealth university outside of the United Kingdom. The School of Anatomy and Surgery was established by Grand Master Fra Nicolás Cotoner at the Sacra Infermeria in Valletta, in 1676. The Sacra Infermeria itself was known as one of the finest and most advanced hospitals in Europe.

Sicily and the Italian mainland

Located just 96 km (60 mi) to the north, Sicily has provided Malta with a virtually continuous exchange of knowledge, ideas, customs and beliefs throughout history. Many modern Maltese families trace their origins to various parts of Sicily and Southern Italy. The geographic proximity has facilitated a considerable amount of intermarriage, cross-migration, and trade between the two groups of islands. It is likely that this was just as true during the period of Arab domination over Sicily as it has been since the Norman conquest of Sicily in 1060 CE. Accordingly, it is difficult to determine whether some of the Semitic influences on Maltese culture were originally imported to Malta from North Africa, or from Sicily. The Sicilian influence on Maltese culture is extensive, and is especially evident in the local cuisine, with its emphasis on olive oil, pasta, seafood, fresh fruits and vegetables (especially the tomato), traditional appetizers such as caponata (Maltese: "kapunata") and rice balls (arancini), speciality dishes such as rice timbale (Maltese: "ross fil-forn"), and sweets such as the cassata and kannoli.

Sicilian influence is also evident in many of the local superstitions, in simple children's nursery rhymes, and in the devotion to certain saints, especially St. Agatha. Centuries of dependence on the Diocese of Palermo brought many Sicilian religious traditions to Malta, including the Christmas crib (Maltese: "il-presepju"), the ritual visiting of several Altars of Repose on Good Friday (Maltese: "is-sepulkri"), and the graphic, grim realism of traditional Maltese religious images and sculpture.

Despite Malta's rapid transformation into a strategic naval base during the British period, the influence of Italian culture on Malta strengthened considerably throughout the 19th century. This was due in part to increasing levels of literacy among the Maltese, the increased availability of Italian newspapers, and an influx of Italian intelligentsia to Malta. Several leaders of the Italian risorgimento movement were exiled in Malta by the Bourbon monarchs during this period, including Francesco Crispi, and Ruggiero Settimo. Malta was also the proposed destination of Giuseppe Garibaldi when he was ordered into exile; however, this never came to pass. The political writings of Garibaldi and his colleague, Giuseppe Mazzini – who believed that Malta was, at heart, part of the emerging Italian nation – resonated among many of Malta's upper- and middle-classes.

France

French rule over Malta, although brief, left a deep and lasting impression on Maltese culture and society. Several of the Grand Masters of the Knights of Malta had been French, and though some French customs and expressions had crept into common usage in Malta as a result (such as the expressions "bonġu" for "good day", and "bonswa" for "good evening", still in use today), Napoleon's garrison had a much deeper impact on Maltese culture. Within six days following the capitulation by Grand Master Hompesch on board l'Orient, Bonaparte had given Malta a Constitution and introduced the Republican concept of Liberté, Egalite, Fraternité to Malta. Slavery was abolished, and the scions of Maltese nobility were ordered to burn their patents and other written evidence of their pedigrees before the arbre de la liberté that had been hastily erected in St. George's Square, at the centre of Valletta. A secondary school system was established, the university system was revised extensively, and a new Civil Code of law was introduced to the legal system of Malta.

Under the rule of General Vaubois civil marriages were introduced to Malta, and all non-Maltese clergymen and women were ordered to leave the Islands. A wholesale plundering of the gold, silver and precious art of Maltese churches followed, and several monasteries were forcibly taken from the religious orders. The Maltese were scandalized by the desecration of their churches. A popular uprising culminated with the "defenestration" of Citizen Masson, commandant of the French garrison, and the summary execution of a handful of Maltese patriots, led by Dun Mikiel Xerri. With the French blockaded behind the walls of Valletta, a National Assembly of Maltese was formed. Petitions were sent out to the King of the Two Sicilies, and to Lord Nelson, soliciting their aid and support. The French garrison capitulated to Nelson in Grand Harbour, on 5 September 1800.

British Malta

British rule, from 1800 to 1964, radically and permanently transformed the language, culture and politics of Malta. Malta's position in the British Empire was unique in that it did not come about by conquest or by colonization, but at the voluntary request of the Maltese people. Britain found in Malta an ancient, Christian culture, strongly influenced by neighbouring Italy and Sicily, and loyal to the Roman Catholic Church. Malta's primary utility to Great Britain lay in its excellent natural harbours and strategic location, and for many decades, Malta was essentially a "fortress colony".

Throughout the 19th century, Malta benefited from increased defence spending by Britain, particularly from the development of the dockyards and the harbour facilities. The Crimean War and the opening of the Suez Canal further enhanced Malta's importance as a supply station and as a naval base. Prosperity brought with it a dramatic rise in the population, from 114,000 in 1842, to 124,000 in 1851, 140,000 in 1870, and double that amount by 1914. Malta became increasingly urbanized, with the majority of the population inhabiting the Valletta and the Three Cities. Malta's fortunes waned during times of peace in the early 20th century, and again after World War II, leading to massive waves of emigration.

Although Malta remained heavily dependent on British military spending, successive British governors brought advances in medicine, education, industry and agriculture to Malta. The British legacy in Malta is evident in the widespread use of the English language in Malta today. English was adopted as one of Malta's two official languages in 1936, and it has now firmly replaced Italian as the primary language of tertiary education, business, and commerce in Malta.

The British period introduced the Neoclassical style of architecture to Malta, evident in several buildings built during this period, including the parish church of Sta. Marija Assunta in Mosta and St Paul's Pro-Cathedral in Valletta, which has a spire dominating the city's skyline.

Neo-Gothic architecture was also introduced to Malta during this period, such as in the Chapel of Santa Maria Addolorata at Malta's main cemetery, and in the Carmelite Church in Sliema. Sliema itself, which developed from a sleepy fishing village into a bustling, cosmopolitan town during the British period, once boasted an elegant seafront that was famed for its Regency style architecture, that was strongly reminiscent of the British seaside town of Brighton.

Impact of World War II

Perhaps as an indirect result of the brutal devastation suffered by the Maltese at the hands of Benito Mussolini's Regia Aeronautica and the Luftwaffe during World War II, the United Kingdom has replaced neighboring Ita ly as the dominant source of cultural influences on modern Malta. The George Cross was awarded to the people of Malta by King George VI of the United Kingdom in a letter dated 15 April 1942[34] to the island's Governor Lieutenant-General Sir William Dobbie, so as to "bear witness to the heroism and devotion of its people"[35] during the great siege it underwent in the early parts of World War II. The George Cross is woven into the flag of Malta and can be seen wherever the flag is flown.

The "culture clash" between pro-British and pro-Italian elements in Malta reached its apex in February 1942, when British Governor Lieutenant-General Sir William Dobbie ordered the deportation of 47 notable Maltese, including Enrico Mizzi, leader of the Nationalist Party, and Sir Arturo Mercieca, Chief Justice of Malta, who were suspected by the Colonial authorities of being sympathetic to the fascist cause. Their exile in Uganda, which lasted until 8 March 1945, was a source of controversy among the Maltese.

British traditions in modern Malta

British traditions that live on in Malta include an efficient civil service, a military that is based on the British model, a Westminster-style parliamentary structure, a governmental structure premised on the rule of law, and a legal system based on common law. Another British legacy in Malta is the widely popular annual Christmas pantomime at the Manoel Theatre. Most Maltese families have adopted turkey and plum pudding as Christmas treats in place of the more traditional Maltese rooster and cassata.

Due to Malta forming a part of the British Empire in the 19th and 20th centuries, and a considerable amount of intermarriage having taken place during that time period, the existence of British or Irish surnames is increasingly common. Examples include: Alden, Atkins, Crockford, Ferry, Gingell, Hall, Hamilton, Harmsworth, Harwood, Jones, Mattocks, Moore, O'Neill, Sladden, Sixsmith, Smith, Strickland, St. John, Turner, Wallbank, Warrington, Kingswell and Woods.[36]

Contemporary culture of Malta

Emigration and immigration

Malta has always been a maritime nation, and for centuries, there has been extensive interaction between Maltese sailors and fishermen and their counterparts around the Mediterranean and into the Atlantic Ocean. More significantly, by the mid-19th century the Maltese already had a long history of migration to various places, including Egypt, Tripolitania, Tunisia, Algeria, Cyprus, the Ionian Islands, Greece, Sicily and Lampedusa. Intermarriage with other nationals (especially Italians and Sicilians) was not uncommon. Migrants would periodically return to Malta, bringing with them new customs and traditions that over time have been absorbed into mainstream Maltese culture.

There was heavy migration from Malta in the early 20th century, and again after World War II until the early 1980s; however the destinations of choice during this period tended to be more distant, English-speaking countries rather than the traditional, Mediterranean littoral. Over 10,000 Maltese settled in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States between 1918 and 1920, followed by another 90,000 – or 30 percent of the population of Malta – between 1948 and 1967.[37] By 1996, the net emigration from Malta during the 20th century exceeded 120,000, or 33.5% of the population of Malta.[38]

Emigration dropped dramatically after the mid-1970s and has since ceased to be a social phenomenon of significance. However, since Malta joined the EU in 2004 expatriate communities emerged in a number of European countries particularly in Belgium and Luxembourg.

Education

Education is compulsory between the ages of 5 and 16 years. While the state provides education free of charge, the Church and the private sector run a number of schools in Malta and Gozo. Most of the teachers' salary in Church schools is paid by the state. Education in Malta is based on the British Model.

Religion

Today, the Constitution of Malta provides for freedom of religion but establishes Roman Catholicism as the state religion. Freedom House and the World Factbook report that 98 percent of the Maltese profess Roman Catholicism as their religion, making Malta one of the most Catholic countries in the world. However, the commissioned by the Church of Malta reports that, as of 2005, only 52.6% of the population attended religious services on a regular basis.

Languages

The national language of Malta is Maltese, the only official Semitic language within the European Union. The Maltese alphabet is based on the Latin alphabet, but uses the diacritically altered letters ż, also found in Polish, as well as the letters ċ, ġ and ħ. The official languages are Maltese and English. Italian, French and German are also widely spoken and taught in secondary schools, though the latter two less so.

Telecommunications

Radio shows, television programs and the easy availability of foreign newspapers and magazines throughout the 20th century further extended and enhanced the impact of both British and Italian culture on Malta. Globalization and increased Internet usage (approx. 78.1% of the population of Malta as of September 2005) is having a significant effect on Maltese culture; as of 22 December 2006, Malta had the fourth highest rate of Internet usage in the world.[39]

Nightlife in Malta

The long, warm summer nights of Malta lend themselves to a vibrant nightlife, which is at odds with Malta's traditional conservatism and the staunch Catholicism of older generations. Clubbing and pub-crawling – especially in the traffic-free zones of Paceville near St. Julian's, and Buġibba – is a rite of passage for Maltese teenagers, young adults and crowds of tourists. Evenings start late and many clubbers continue the festivities into the early hours of the morning. Clubs frequently have large outdoor patios, with local and visiting DJs spinning a mix of Euro-beat, House, chill-out, R&B, hardcore, rock, trance, techno, retro, old school, and classic disco. Pubs, especially Irish pubs, are often the meeting place of choice for the start of a night of clubbing.

Laid back wine bars are increasingly popular among young professionals and the more discriminating tourists, and are popping up in the kantinas of some of the more picturesque, historic cities and towns, including Valletta and Vittoriosa. They typically offer a mix of local and foreign wines, traditional Maltese appetizer platters, and occasionally, live entertainment.

Despite rapidly increasing tolerance and acceptance of alternative lifestyles, Malta offers its gay and lesbian locals and visitors less nightlife options than other Southern European destinations. With the exception of several staple bars (including Tom's, Valletta and Klozett, Paceville), gay bars in Malta have a tendency to pop up, relocate, and disappear from one summer season to the next. However, the local gay population is usually very much in evidence – and welcome – at the mainstream clubs of Paceville and elsewhere.

Transportation

Car ownership in Malta is the fourth highest in Europe, given the small size of the islands. Like in the UK, traffic drives on the left.

The old Maltese buses, formerly ex-British Armed forces vehicles, were Malta's main domestic mode of transportation until 2011. From then onwards bus services were run by Arriva. There has also been a railway in the past between Valletta and the Mtarfa army barracks.

A regular ferry system connects the two main Maltese islands, via the harbours of Ċirkewwa and Marsamxett in Malta, and Mġarr in Gozo. There are also regular ferry services between the Grand Harbour and neighbouring Sicily. A busy cruise liner terminal has been developed on the Valletta side of Grand Harbour; however, Malta's primary connection to the outside world is its airport at Luqa.

Literature

The emergence of Maltese literature

The oldest extant literary text in the Maltese language is Pietru Caxaro's poem, Il-Kantilena (circa 1470 to 1485) (also known as Xidew il-Qada), followed by Gian Francesco Bonamico's sonnet of praise to Grand Master Nicolò Cotoner, Mejju gie' bl'Uard, u Zahar (The month of May has arrived, with roses and orange blossoms), circa 1672. The earliest known Maltese dictionary was written by Francois de Vion Thezan Court (circa 1640). In 1700, an anonymous Gozitan poet wrote Jaħasra Mingħajr Ħtija (Unfortunately Innocent). A Maltese translation of the Lord's Prayer appeared in Johannes Heinrich Maius's work Specimen Lingua Punicæ in hodierna Melitensium superstitis (1718). A collection of religious sermons by a certain Dun Ignazio Saverio Mifsud, published between 1739 and 1746, is now regarded as the earliest known Maltese prose. An anonymous poem entitled Fuqek Nitħaddet Malta (I am talking about you, Malta), was written circa 1749, regarding the uprising of the slaves of that year. A few years later, in 1752, a catechism entitled Tagħlim Nisrani ta' Dun Franġisk Wizzino (Don Francesco Wizzino's Christian Teachings) was published in both Maltese and Italian. The occasion of Carnival in 1760 saw the publication of a collection of burlesque verses under the heading Żwieġ la Maltija (Marriage, in the Maltese Style), by Dun Feliċ Demarco.

A child of the Romanticism movement, Maltese patriot Mikiel Anton Vassalli (1764–1829) hailed the emergence of literary Maltese as "one of the ancient patrimonies ... of the new emerging nation," seeing this nascent trend as: (1) the affirmation of the singular and collective identity, and (2) the cultivation and diffusion of the national speech medium as the most sacred component in the definition of the patria and as the most effective justification both for a dominated community's claiming to be a nation and for the subsequent struggle against foreign rulers.[40]

Between 1798 and 1800, while Malta was under the rule of Napoleonic France, a Maltese translation of L-Għanja tat-Trijonf tal-Libertà (Ode to the Triumph of Liberty), by Citizen La Coretterie, Secretary to the French Government Commissioner, was published on the occasion of Bastille Day.

The first translation into Maltese of a biblical text, the Gospel of St. John. was published in 1822 (trans. Ġużeppi Marija Cannolo), on the initiative of the Bible Society in Malta. The first Maltese language newspaper, l-Arlekkin Jew Kawlata Ingliża u Maltija (The Harlequin, or a mix of English and Maltese) appeared in 1839, and featured the poems l-Imħabba u Fantasija (Love and Fantasy) and Sunett (A Sonnett).

The first epic poem in Maltese, Il-Ġifen Tork (The Turkish Caravel), by Giovanni Antonio Vassallo, was published in 1842, followed by Ħrejjef bil-Malti (Legends in Maltese) and Ħrejjef u Ċajt bil-Malti (Legends and Jokes in Maltese) in 1861 and 1863, respectively. The same author published the first history book in the Maltese language, entitled Storja ta' Malta Miktuba għall-Poplu (The People's History of Malta), in 1862.

1863 saw the publication of the first novel in Maltese, Elvira Jew Imħabba ta' Tirann (Elvira, or the Love of a Tyrant), by the Neapolitan author, Giuseppe Folliero de Luna. Anton Manwel Caruana's novel, Ineż Farruġ (1889), was modelled on traditional Italian historical novels, such as Manzoni's I promessi sposi.

Diglossia

The development of native, Maltese literary works has historically been disrupted by diglossia. For many centuries, Maltese was considered "the language of the kitchen and the workshop", while Italian was the language of literature, law and commerce.[41] Until the early 20th century, the vast majority of literary works by the Maltese were written in Italian, although examples of written Maltese from as far back as the 16th century exist. In early Maltese history, diglossia manifested itself in the co-existence of an ancient Phoenician language and the language of a series of rulers, most notably, Latin, Greek, Arabic, Sicilian, French, Spanish and Italian, and from 1800 onwards, English. The Maltese language today is heavily overlaid with Romance and English influences as a result.

According to Prof. Oliver Friggieri:

Maltese writers developed an uninterrupted local "Italian" literary movement which went on up to about four decades ago, whereas Maltese as a literary idiom started to coexist on a wide scale in the last decades of the 19th century. Whilst Maltese has the historical priority on the level of the spoken language, Italian has the priority of being the almost exclusive written medium, for the socio-cultural affairs, for the longest period. The native tongue had only to wait for the arrival of a new mentality which could integrate an unwritten, popular tradition with a written, academically respectable one.[40]

Maltese writers

- Clare Azzopardi

- Lina Brockdorff

- Rużar Briffa

- Anton Buttigieg

- Ray Buttigieg

- Charles Casha

- Pietru Caxaro

- Ninu Cremona

- Lou Drofenik

- Francis Ebejer

- Henry Frendo

- Oliver Friggieri

- Ġużè Galea

- Herbert Ganado

- Mary Meilak

- Doreen Micallef

- Gioacchino Navarro

- Dun Karm Psaila

- Frans Said

- Alfred Sant

- Frans Sammut

- Mikiel Anton Vassalli

- Trevor Żahra

Notable writers of Maltese descent

Performing arts

Music

Theatre

The theatres currently in use for live performances in Malta and Gozo range from historic purpose-built structures to modern constructions, to retrofit structures behind historic façades. They host local and foreign artistes, with a calendar of events that includes modern and period drama in both national languages, musicals, opera, operetta, dance, concerts and poetry recitals. The more notable theatrical venues include:

- St. James Cavalier Centre for Creativity, Valletta: Built as a raised gun platform at the entrance to the walled city c. 1566, retrofitted and inaugurated as a cultural centre on 22 September 2000

- Republic Hall, Valletta: Built as the Sacra Infermeria, the main hospital of the Knights of Malta in 1574, retrofitted and inaugurated as part of the multipurpose Mediterranean Conference Centre on 11 February 1979

- MITP (Mediterranean Institute Theatre Programme), Valletta: Housed in the Collegium Melitensæ, c. 1592

- Manoel Theatre, Valletta: Malta's National Theatre, inaugurated 9 January 1732

- Pjazza Teatru Rjal, Valletta: open-air theatre in the ruins of the Royal Opera House, inaugurated 8 August 2013

- Salesian Theatre, Sliema: Originally known as Juventutis Domus, inaugurated in 1908

- Astra Theatre, Victoria, Gozo: inaugurated 20 January 1968

- Aurora Opera House, Victoria, Gozo: inaugurated 1976

Online Video

Popular Maltese YouTuber Grandayy rose to popularity posting video memes and note block covers. As of 18 July 2019, he has 2.3 million subscribers on YouTube, 2.6 million followers on Instagram, 781.2K followers on Twitter and 100,137 monthly listeners on Spotify. He is the 1st and 2nd most popular person on social media in Malta, along with his 2nd channel grande1899.

Visual arts

The Neolithic temple builders (3800–2500 BCE) endowed the numerous temples of Malta and Gozo with intricate bas relief designs, including spirals evocative of the tree of life and animal portraits, designs painted in red ochre, ceramics, and a vast collection of human form sculptures, particularly the Venus of Malta. These can be viewed at the temples themselves (most notably, the Hypogeum and Tarxien Temples), and at the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta.

The Roman period introduced highly decorative mosaic floors, marble colonnades and classical statuary, remnants of which are beautifully preserved and presented in the Roman Domus, a country villa just outside the walls of Mdina. The early Christian frescoes that decorate the catacombs beneath Malta reveal a propensity for eastern, Byzantine tastes. These tastes continued to inform the endeavours of medieval Maltese artists, but they were increasingly influenced by the Romanesque and Southern Gothic movements. Towards the end of the 15th century, Maltese artists, like their counterparts in neighbouring Sicily, came under the influence of the School of Antonello da Messina, which introduced Renaissance ideals and concepts to the decorative arts in Malta.[42]

The artistic heritage of Malta blossomed under the Knights of St. John, who brought Italian and Flemish Mannerist painters to decorate their palaces and the churches of these islands, most notably, Matteo Perez d'Aleccio, whose works appear in the Magisterial Palace and in the Conventual Church of St. John, and Filippo Paladini, who was active in Malta from 1590 to 1595. For many years, Mannerism continued to inform the tastes and ideals of local Maltese artists.[42]

The arrival in Malta of Caravaggio, who painted at least seven works during his 15-month stay on these islands, further revolutionized local art. Two of Caravaggio's most notable works, The Beheading of St. John the Baptist, and St. Jerome are on display in the Oratory of St. John's Co-Cathedral, Valletta. His legacy is evident in the works of local artists Giulio Cassarino (1582–1637) and Stefano Erardi (1630–1716). However, the Baroque movement that followed was destined to have the most enduring impact on Maltese art and architecture. The severe, Mannerist interior of St. John's Co-Cathedral was transformed into a Baroque masterpiece by the glorious vault paintings of the celebrated Calabrese artist, Mattia Preti. Preti spent the last 40 years of his life in Malta, where he created many of his finest works, now on display in the Museum of Fine Arts, in Valletta. During this period, local sculptor Melchiorre Gafà (1639–1667) emerged as one of the top Baroque sculptors of the Roman School.

Throughout the 18th century, Neapolitan and Rococo influences emerged in the works of Luca Giordano (1632–1705) and Francesco Solimena (1657–1747), and local artists Gio Nicola Buhagiar (1698–1752) and Francesco Zahra (1710–1773). The Rococo movement was greatly enhanced by the relocation to Malta of Antoine de Favray (1706–1798), who assumed the position of court painter to Grand Master Pinto in 1744.

Neo-classicism made some inroads among local Maltese artists in the late 18th century, but this trend was reversed in the early 19th century, as the local Church authorities – perhaps in an effort to strengthen Catholic resolve against the perceived threat of Protestantism during the early days of British rule in Malta – favoured and avidly promoted the religious themes embraced by the Nazarene movement of artists. Romanticism, tempered by the naturalism introduced to Malta by Giuseppe Calì, informed the "salon" artists of the early 20th century, including Edward and Robert Caruana Dingli.

A National School of Art was established by Parliament in the 1920s, and during the reconstruction period that followed the Second World War, the local art scene was greatly enhanced by the emergence of the "Modern Art Group", whose members included Josef Kalleya (1898–1998), George Preca (1909–1984), Anton Inglott (1915–1945), Emvin Cremona (1919–1986), Frank Portelli (b. 1922), Antoine Camilleri (b. 1922) and Esprit Barthet (b. 1919). Malta has a thriving contemporary arts scene. Valletta is the European Capital of Culture for 2018. Malta has produced a pavilion for the Venice Biennale in 2017 and 1999. There are numerous contemporary arts spaces, such as Blitz and Malta Contemporary Art, which support and nurture Maltese and international artists.

Traditional crafts

Lace making

Traditional Maltese lace (Maltese: bizzilla) is bobbin lace of the filet-guipure variety. It is formed on a lace pillow stuffed with straw, and frequently features the eight-pointed Maltese cross, but not necessarily. Genoese-style leafwork is an essential component of the traditional designs. Nowadays, Malta lace is usually worked on ivory-coloured linen, although historically it was also worked on black or white silk. It is typically used to make tablecloths, placemats and serviettes, and is periodically featured in couture, and in traditional Maltese costume.

Lace making has been prevalent in Malta since the 16th century, and was probably introduced to the Islands at roughly the same time as in Genoa. Lace was included with other articles in a bando or proclamation enacted by Grand Master Ramon Perellos y Roccaful in 1697, aimed at repressing the wearing of gold, silver, jewellery, gold cloth, silks and other materials of value.[43]

There was a resurgence of lace-making in Malta around 1833, which has been attributed to a certain Lady Hamilton-Chichester.[44] Queen Victoria is said to be particularly fond of wearing Malta lace. In 1839, Thomas McGill noted in A Handbook, or Guide, for Strangers visiting Malta, that:

"the females of the island make also excellent lace; the lace mitts and gloves wrought by the Malta girls are bought by all ladies coming to the island; orders from England are often sent for them on account of their beauty and cheapness."

Maltese lace was featured in the Great Exhibition held in London in 1851. Lacemaking is currently taught in Government trade schools for girls, and in special classes organized by the Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. Lacemaking is essentially a cottage industry throughout Malta and Gozo.

Filigree

Filigree work (Maltese: filugranu) in gold and silver flourished in Malta under the rule of the Knights. This included gold and silver ornamental flower garlands (Maltese: ganutilja) and embroidery (Maltese: rakkmu). Filigree items that are ubiquitous in Maltese jewellery stores and crafts centres include brooches, pendants, earrings, flowers, fans, butterflies, jewelboxes, miniature dgħajjes (fishing boats) and karrozzini (horse-drawn cabs), the Maltese Cross and dolphins.

Sport

Throughout the 1990s, organized sports in Malta experienced a renaissance through the creation of a number of athletic facilities, including National Stadium and a basketball pavilion in Ta' Qali, an Athletic Stadium and Tartan Track for athletics, archery, rugby, baseball, softball and netball at Marsa, the National Swimming Pool Complex on University of Malta grounds at Tal-Qroqq, an enclosed swimming pool complex at Marsascala, a mechanized shooting range at Bidnija, and regional sports complexes on Gozo, and in Cottonera and Karwija.

In 1993 and again in 2003, Malta hosted the Games of the Small States of Europe. Since 1968, Malta has also hosted the annual Rolex Middle Sea Race, organized by the Royal Malta Yacht Club. The race consists of a 607-mile (977 km) route that starts and finishes in Malta, via the Straits of Messina and the islands of Pantelleria and Lampedusa.

Football

Malta's "national" sport is football. Many Maltese avidly follow English and Italian matches. Malta also has its own national team; however, every four years the World Cup typically sees Maltese loyalties divided between the teams of England and Italy, and a victory by either of these two teams inevitably leads to spontaneous, and very boisterous street parties and carcades all over the Maltese Islands the Euro 2020 final, played between England and Italy, having led to some of the largest in recent memory.

Golf

The Marsa sports complex includes a 68 par golf course, maintained by the Royal Malta Golf Club

Boċċi

Another common sport in Malta is a local variety of the game of bocce or boules (Maltese: boċċi). In Malta, the game is played on a smooth surface covered with coarse-grained sand, with teams of three players. Boċċi clubs are common throughout Malta, but also among the Maltese emigrant communities in Australia, Canada and the United States.

Waterpolo

Passion for waterpolo runs high in Malta and Gozo throughout the summer months. Prowess in this particular sport was the impetus for the foundation, in 1925, of a local Amateur Swimming Association, and Malta's first participation in the Olympic Games, at the IXth Olympiad in Amsterdam, 1928.[45]

Horse racing

Horse racing has a long tradition in Malta. The popular, bareback horse races that take place annually on Saqqajja Hill, in Rabat on 29 June date back to the 15th century. These races form part of the traditional celebrations of the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul (il-Festa tal-Imnarja), and were greatly encouraged by the Knights of Malta, especially during the reign of Grand Masters de Verdalle and de Lascaris-Castellar. The Knights took these races very seriously: Bonelli records a proclamation issued by the Grand Masters of the era, which threatened anyone caught interfering with or obstructing a racing horse with forced labour on board the galleys of the Knights.[46] The tradition was revived and strengthened after the First World War under British Governor, Lord Plumer. The racecourse at Marsa, which was founded in 1868, boasted one of the longest tracks in Europe, at one and three quarter miles (2.8 km). The first Marsa races were held on 12 and 13 April 1869.[47]

Il-Gostra

Il-Gostra is a traditional sport enjoyed in many seaside towns across Malta with its origins dating back to the middle ages. The sport involves leaning a large wooden pole (normally 10-16 meters in length) over the ocean and covering it in animal fat. The objective of the game is to grab one of three flags at the end of the pole by running up the greased pole.[48] Each Flag has a different prize, the blue and white flag is dedicated to St Mary, a yellow and white flag representing the Vatican, and Belgium tricolour flag representative of St Julian.[49] The sport is still practiced today and has recently garnered worldwide media attention.[50]

See also

References

- ↑ "The OTS Foundation – educational program provider, organizing, exhibiting, operating, researching". The OTS Foundation. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ Aberystwyth, The University of Wales Archived 12 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ David Trump et al., Malta Before History (2004: Miranda Publishers)

- ↑ Daniel Cilia, "Malta Before Common Era", in The Megalithic Temples of Malta. Accessed 28 January 2007.

- ↑ Salvatore Piccolo, Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens in Sicily. Abingdon: Brazen Head Publishing, 2013.

- ↑ J. Cassar Pullicino, "Determining the Semitic Element in Maltese Folklore", in Studies in Maltese Folklore, Malta University Press (1992), p. 68.

- ↑ "Phoenician and Punic remains in Malta – The Malta Independent". Independent.com.mt. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ "Phoenicians Online Extra @ National Geographic Magazine". ngm.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- 1 2 C. Capelli, N. Redhead, N. Novelletto, L. Terrenato, P. Malaspina, Z. Poulli, G. Lefranc, A. Megarbane, V. Delague, V. Romano, F. Cali, V.F. Pascali, M. Fellous, A.E. Felice, and D.B. Goldstein; "Population Structure in the Mediterranean Basin: A Y Chromosome Perspective," Archived 28 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine Annals of Human Genetics, 69, 1–20, 2005. Last visited 8 August 2007.

- 1 2 A.E. Felice; "The Genetic Origin of Contemporary Maltese," The Sunday Times of Malta, 5 August 2007.

- ↑ E. Magri, Ħrejjef Missierijietna, Book III: Dawk li jagħmlu l-Ġid fid-Dinja, no. 29 (1903), p. 19

- ↑ L. Cutajar, "X'Igħidu l-Għarab fuq Malta", Il-Malti (1932), pp. 97–8.

- ↑ G. Finotti, La Reggenza di Tunisi, Malta (1856), pp. 108–9.

- ↑ Archived 15 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Ibn 'Abd al-Mun'im al-Himyarī, ed. Iḥsan 'Abbās (Beirut, 1975), cited in J.M. Brincat, Malta 870–1054: Al-Himyarī's Account and its Linguistic Implications, Malta, 2d. rev. ed. (1995)

- 1 2 "Xewkija Local Council - Gozo - Malta". Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2009. Xewkija Local Council

- ↑ E. Winklemann, Ex Act. Imperii Ined. seculi XIII et XIV, tom. I, pp. 713 et seq. (1880) Innsbruck; cited by J. Cassar Pullicino, in "Determining the Semitic Element in Maltese Folklore", in Studies in Maltese Folklore, (1992) Malta University Press, p. 71.

- ↑ Zarb, T. Folklore of An Island, PEG Ltd, 1998

- ↑ "Heritage Malta". Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2009. Heritage Malta

- ↑ Godfrey Wettinger

- 1 2 Tayar, Aline P'nina: "The Jews of Malta | The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot". Accessed 5 January 2007.

- ↑ E. Ochs and B. Nantet, "Il y a aussi des juifs à Malte" Archived 29 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hecht, Esther: The Jewish Traveler: Malta Archived 6 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine in Hadassah Magazine. December 2005. Accessed 28 December 2006.

- ↑ A. Bonnici, "Superstitions in Malta towards the middle of the Seventeenth Century in the Light of the Inquisition Trials," in Melita Historica, Vol. 4, No. 3, 1966, pp. 156–7.

- ↑ G. Wettinger, cited by J. Cassar Pullicino, in "Determining the Semitic Element in Maltese Folklore", in Studies in Maltese Folklore, (1992) Malta University Press, pp. 71 and 72.

- ↑ Università degli Studi di Roma, Missione archeologica italiana a Malta: Rapporto preliminare della campagna 1966, Rome (1967), p. 133.

- ↑ Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E. (18 September 1975). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521086912.

- ↑ Agius, Albert, Qwiel, Idjomi, Laqmijiet Maltin (Dan il-ktieb jiġbor fih numru kbir ta qwiel u ta' idjomi. L-awtur jagħti wkoll tifsiriet kif bdew il-laqmijiet kollettivi tan-nies ta l-ibliet u l-irħula tagħhna etċ)

- ↑ G.F. Abela, Della Descrittione di Malta, (1647) Malta.

- ↑ A. Luttrell, The Making of Christian Malta: From the Early Middle Ages to 1530, Aldershot, Hants.: Ashgate Varorium, 2002.

- ↑ Castillo, Dennis Angelo (2006). The Maltese Cross: A Strategic History of Malta. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32329-1.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 August 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Archive - ↑ Victor Paul Borg, "Architecture," in A Rough Guide to Malta and Gozo (2001) Archived 6 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Viewed online on 10 February 2007.

- ↑ "BBC:On This Day". BBC News. 15 April 1942. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- ↑ "Merlins Over Malta – The Defenders Return". Archived from the original on 16 April 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- ↑ "Help.com – Live Chat Software". Help.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ "Multicultural Canada". Multiculturalcanada.ca. 28 September 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ "The 1996 CIA World Factbook page on Malta". Umsl.edu. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ "ITU: Committed to connecting the world". ITU. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- 1 2 "AccountSupport". Aboutmalta.com. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ "AccountSupport". Aboutmalta.com. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- 1 2 Verstraete/BBEdit, Anton. "An Overview of the Art of Malta". Hopeandoptimism.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ Ġużé Cassar Pullicino, "Bizzilla: A Craft Handed over by the Knights", in MALTA – This Month (September 1997).

- ↑ Mincoff and Marriage, Pillow Lace (1907)

- ↑ "Ministry of Education -". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- ↑ L. Bonelli, "Il Dialetto Maltese," in Supplementi periodici all'Archivio Glottologico Italiano, Dispensa VIII, 1907, p. 16. Cited by J. Cassar Pullicino, in "Animals in Maltese Folklore," in Studies in Maltese Folklore, supra., at pp. 195–6.

- ↑ "MALTA RACING CLUB". 28 March 2007. Archived from the original on 28 March 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ "Customs & Traditions : Air Malta". airmalta.com. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ↑ Adrian (13 September 2016). "Gostra is a Sport Featuring People Running Up A Greasy Pole". Ripley's Believe It or Not!. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ↑ "St Julian's feast celebrated with gostra and hunting traditions". Times of Malta. 30 August 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

.jpg.webp)