.pdf.jpg.webp)

Dachau is a 72-page investigation report by the 7th US Army on Dachau, one of the concentration camps established by Nazi Germany. The report details the mass murder and mass atrocities committed at Dachau by the SS and other personnel. Following the liberation of the camp by the 7th US Army on 29 April 1945, the report was prepared during the following one or two weeks and published in May. In addition to a preface, the report contains three independent reports which partly overlap thematically. Although it contains some errors, the report is considered one of the first studies on the Nazi concentration camps.

Background

Built in 1933, Dachau was one of the first Nazi concentration camps. Though a large number of prisoners were executed, the camp was more of a large scale prison and internment camp and not part of the complex of the extermination camps such as the Auschwitz concentration camp. In the final phase of the Second World War, the living conditions of the prisoners in Dachau concentration camp drastically deteriorated, causing the death rate in the camp to rise rapidly. Many inmates of the overcrowded camp suffered from malnutrition and the untenable hygienic conditions. Evacuation transports from other concentration camps and a rampant typhus epidemic exacerbated the catastrophic camp conditions. From January to April 1945 alone, more than 13,000 prisoners died of disease or exhaustion in the Dachau concentration camp and the affiliated subcamps; many of the bodies remained unburied on the grounds. In addition, thousands of prisoners lost their lives on death marches to the south. Shortly before the arrival of the US Army, there were more than 32,000 emaciated prisoners in Dachau concentration camp; about 8,000 of whom were bedridden.[1]

After the Dachau concentration camp was liberated on 29 April 1945 by units of the 42nd and 45th Infantry Divisions of the Seventh United States Army, the liberators found 3,000 corpses and several thousand people vegetating. In addition, there was a strong smell of decay lying on the camp.[2] Even before entering the camp grounds, the US soldiers had discovered hundreds of dead concentration camp prisoners in the death train from Buchenwald parked on a siding, most of whom had died of hunger, debilitation or disease during transport to Dachau concentration camp.[3][4] Battalion commander Felix Sparks later reported:[2]

During the early period of our entry into the camp, a number of company men all battle hardened veterans, became extremely distraught. Some cried, while others raged.

Upset by these traumatic experiences, spontaneous shootings of captured SS men by US soldiers occurred.[2]

Origins and authors

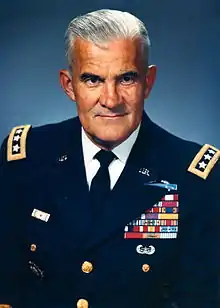

When Colonel William Wilson Quinn, Assistant Chief of Staff of the G2 Military Intelligence of the 7th US Army, learned of the shocking and indescribable impressions of his comrades after the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp, he immediately went to the site to see the situation for himself. He remarked that the mass crimes found there were beyond his imagination,[5] and that no one would have believed the atrocities committed in the camp at the time. As a result, he decided to immediately document what he had experienced, resulting in this investigative report.[6] The preface, signed by Quinn, states:[7]

DACHAU, 1933-1945, will stand for all time as one of history's most gruesome symbols of inhumanity. There our troops found (...) cruelties so enormous as to be incomprehensible to the normal mind. Dachau and death were synonymous.

Quinn formed several teams to gather information about what happened in the camp, including taking statements from former prisoners. In particular, he was also interested in finding out what the population of the nearby town of Dachau knew about the concentration camp and what they thought about it.[5] Involved in the report were the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) and the Psychological Warfare Branch (PWB) of the 7th US Army. The report is based primarily on interviews with liberated detainees by US intelligence officers and on field investigations. Members of the unofficial international committee of the liberated camp, which had been formed shortly before the liberation, assisted in this.

Composition and publication

The report was completed rather quickly, within the span of one to two weeks.[8][9] The report is divided into four parts, listed in a table of contents on the third page of the document. Part I features the foreword by William Wilson Quinn while Part II was prepared by the Office of Strategic Services. Part III was prepared by the Psychological Warfare Branch and Part IV prepared by the Counter Intelligence Corps. Parts II to IV partly overlap thematically, since they were prepared as individual reports that were largely independent of each other. According to the preface, the reports were deliberately not combined into a common document with a uniform style, as doing so would have "seriously weaken[ed] [their] realism".[10] In the summary preceding the second part of the report, it noted that the report does not intend to be a comprehensive or exhaustive account of Dachau Concentration Camp, and that work was already being done on further, more comprehensive reports.[11] Thus, in preparation for the War Crimes Trial Program, American investigators conducted investigations from April 30, 1945 to August 7, 1945 to determine who was responsible for the crimes associated with the Dachau complex. This investigation report, completed on 31 August 1945, was the basis for the Dachau Camp Trial.[12]

The 649th Engineer Topographic Battalion of the U.S. Army took over the printing and duplication of the report, which was published in typewritten form.[13] By May 1945, 10,000 copies had aready been circulated.[5] The Dachau Report was, according to the memoirs of William W. Quinn initially intended only as an internal report for use in the US Army, but then got to journalists unplanned through display in a press room, making it known to the public.[14] It soon circulated among US soldiers and members of the press.[6][15]

The public was promptly informed about the conditions found in Dachau concentration camp. Several journalists accompanied the US soldiers during the liberation of Dachau concentration camp, including Marguerite Higgins, who was a war correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune. She wrote the "first, though belatedly transmitted, report from Dachau."[16] As early as 1 May 1945, many newspapers published articles to this effect. Film crews also arrived at the liberated camp. At the invitation of Dwight D. Eisenhower, delegations of American politicians as well as editors-in-chief and publishers went to the site on 2 and 3 May 1945 respectively to get a picture of the situation. According to Harold Marcuse, the aim was "to convince the American public of the extent and authenticity of the atrocities through their reporting".[17]

Content

Summary

.pdf.jpg.webp)

The report presents the Dachau concentration camp complex comprehensively and from different perspectives. Since the American investigators were in the camp as liberators, they were able to rely on a high level of cooperation and willingness to testify[18] from the liberated prisoners; a part of the report consists of eyewitness accounts of the inmates, as well as occasional longer excerpts from diaries and personal accounts of the experiences of individual prisoners.[19] A large part of the report consists of factual analysis and summaries by the authors of the report.

The sociology and social psychology of the system of prisoners and prisoner groups, their interactions with each other[20] the commanding SS, and the so-called prisoner administration or labour administration[21] are detailed through an organizational chart.[22] The report also contains statistical listings of prisoner numbers and the proportion of different nationalities[23] and the crimes charged, as well as figures on deaths in the camp, which rose sharply from autumn 1944 onwards.[24] Accounts of the social dynamics among the prisoners[20] also make up a large part of the report, such as the interaction between prisoner groups of different nationalities, and how these differences were deliberately instrumentalised by the SS for purposes of control and oppression; for example, German inmates were placed in administrative positions in order to stir anti-German sentiment among non-German inmates.[25]

Another section deals with the pseudoscientific, inhumane human experiments. These included, for example, the deliberate infection of healthy inmates with serious, potentially deadly infectious diseases without subsequent treatment. In other "experiments", prisoners were forcefully immersed in tanks filled with icy water at about 1 °C (34 °F) for long periods of time until they became unconscious.[26]

Throughout the report there are descriptions of various aspects of the extremely harsh living conditions, both physical and psychological, which were forced upon the inmates and determined their struggle for survival.[27] The OSS wrote in section I of the report:[28]

These factors dividing people in a normal type of society are totally inapplicable to the situation at Dachau where people lived the most abnormal kind of existence imaginable. Regardless of origin, education, wealth, politics, or religion, people living in Dachau for a certain time were gradually reduced to the most primitive and cruel form of existence – motivated almost exclusively by fear of death. They no longer acted as former bankers, workers, priests, Communists, intellectuals or artists, but primarily as individuals trying to survive in the physical conditions of Dachau, i.e., trying to escape the constantly threatening death by starvation, freezing, or execution.

A large section is also dedicated to the description of the control, repression and terror system that the SS had set up in Dachau, just as in all other German concentration camps.[29] Selected inmates who were in the camp for criminal offences such as murder or robbery were known as "criminals" and given special positions in the hierarchy of the camp. They were used by the SS to suppress and control the larger number of people imprisoned for political reasons ("politicals") through psychological and physical terror.[30] This included, for example, reducing or depriving food rations, threats, harassment and physical violence up to torture and murder of political prisoners by "criminals".[31] These acts were usually directly ordered by the SS or done to accomplish a particular goal set out by the SS for one or more criminal inmates.[32] Several pages also document the various ways inmates were executed at Dachau.[33]

Dachau also discusses the history of the Dachau concentration camp, which existed as early as 1933 and is considered the first camp of its kind in Nazi Germany.[34] The US investigators also conducted extensive interviews with residents of the town of Dachau, which was located near the camp. While doing so, they particularly tried to find individuals among the mass of allegedly unsuspecting and innocent residents who had in some way politically resisted. Their statements, including their assessment of their fellow residents' attitudes, were documented.[35]

Other sections deal with the liberation of the camp by the US Army and the events that followed[36] as well as with the physical structure or organization of the camp[37] along with the daily routine of the prisoners.[38]

Gallery

.pdf.jpg.webp) Aerial photograph of the camp by an American reconnaissance plane, p. 2

Aerial photograph of the camp by an American reconnaissance plane, p. 2.pdf.jpg.webp) Bodies of prisoners who died of conditions in the camp, p. 41

Bodies of prisoners who died of conditions in the camp, p. 41.pdf.jpg.webp) Picture of three liberated inmates, two wearing the black and white striped concentration camp inmate clothing, p. 13

Picture of three liberated inmates, two wearing the black and white striped concentration camp inmate clothing, p. 13.pdf.jpg.webp) Introduction Part III (p. 16): "(...) the first impression comes as a complete, a stunning shock." Picture of murdered prisoners of the Außenlager Kaufering IV on the railway line Kaufering-Landsberg[39]

Introduction Part III (p. 16): "(...) the first impression comes as a complete, a stunning shock." Picture of murdered prisoners of the Außenlager Kaufering IV on the railway line Kaufering-Landsberg[39]

Chapters

Part I. Foreword

The three-paragraph preface by Colonel William W. Quinn includes the following statement:

No words or pictures can carry the full impact of these unbelievable scenes but this report presents some of the outstanding facts and photographs in order to emphasize the type of crime which elements of the SS committed thousands of times a day, to remind us of the ghastly capabilities of certain classes of men, to strengthen our determination that they and their works shall vanish from the earth.[7]

Part II. Dachau, Concentration Camp - OSS Section

The OSS section, introduced by a Summary (pp. 3, 4), comprises twelve pages and is divided into the sections History (pp. 5 to 6), Composition (pp. 6 to 8), Organization (pp. 9 to 11) and Groupings of Prisoners (pp. 11 to 15). The summary is followed by a brief outline of the history of Dachau Concentration Camp from 1933 to 1945, describing the increasing number of prisoners in the camp, the expansion of the groups of prisoners admitted and the constantly expanding network of affiliated subcamps. Furthermore, the chapter describes the increasing overcrowding of the camp during the Second World War, exacerbated by incoming evacuation transports from other camps, which led to a considerable increase in the death rate among the prisoners due to hunger and disease in the final phase of the camp.

The following section is devoted to the composition of the prisoner groups, whereby nationality and the reason for admission are mentioned as the main distinguishing features. Furthermore, the identification of prisoners in the concentration camps and the contrast between political (Reds) and so-called criminal prisoners (Greens) are explained. Finally, the section notes the irrelvance of previous social distinctions given the camp's poor conditions, leading to prisoners being "gradually reduced to the most primitive and cruel form of existence—motivated almost exclusively by fear of death." In the Organization section, the terror system in the camp is explained, which consisted of external control by the camp SS and internal control by the function prisoners appointed by the SS. The following Prisoner Groups section describes functional posts for prisoners and, within the framework of internal organization, the key position of the Labour Deployment Department is emphasized. The second part concludes with a description of prisoner groups formed on the basis of nationality and the International Prisoners' Committee.

Part III. Dachau, Concentration Camp and Town - PWS Section

The third part of the report is from the PWS section is eleven pages long. It is divided into the Introduction (pp. 16 to 18), The Camp (pp. 18 to 21), The Townspeople (pp. 22 to 25) and Conclusion (pp. 25 to 26) sections. In the introduction, the subject of the study is derived by prefacing the following remarks with two questions: What is currently known about the situation in the camp, and what did the Dachau townspeople know about the events in the camp, and what was their corresponding attitude towards it? To answer the first question, 20 former political prisoners were interviewed. The Dachau camp survivors told the American interrogators about everyday life in the camp, which was characterized by hunger, illness and punishment, mass crimes. They further detailed the role of the SS guards and the prisoner functionaries, camp hierarchies and the poor medical care. On the other hand, citizens of the nearby town of Dachau were interviewed to the second question. The questioning of the Dachau citizens revealed that the existence of the camp was known; however, many of them remarked to the interrogators that they had known nothing about what was going on in the camp and the mass crimes. This section also lists some of the explanations given in German, such as "Wir sind aberall belogen worden" (We were all lied to) or "Was konnten wir tun?" (What could we do?). However, some political opponents to the Nazi regime from the town of Dachau stated that the events in the camp had been known in the town. The interrogators concluded that the overwhelming majority of the town population had brought guilt upon themselves through alleged ignorance and lack of civil courage.

Part IV. Dachau, Concentration Camp - CIC Detachment

.pdf.jpg.webp)

The main part of the report, prepared by the CIC, comprises forty pages. This part is divided into the Memorandum (pp. 27 and 28), Liberation (pp. 28 to 30), Life at Dachau (pp. 30 to 34), Diary of E.K. (pp. 35 to 45), Statement by E.H. (pp. 35 to 45), Special Case Reports (pp. 61 to 63) and Miscellaneous (p. 63ff.) sections. The Memorandum leads on to the next section, which deals with the circumstances of the liberation of the camp. The section Life at Dachau deals with the transport of prisoners to the camp, the admission procedure after arrival, and the harsh everyday life in the camp. The following pages contain a detailed account of the cruel human experiments on prisoners and of the types of executions in the camp.

The special case reports focus on people with connections to Dachau concentration camp, including the camp medical doctor Claus Schilling, who was executed for his crimes against the Dachau prisoners in 1946, and the SS members of the camp, Wilhelm Welter, Franz Böttger and Johann Kick. The report concludes with the section Miscellaneous, where the structure of the camp SS is detailed. Several tables showing the list of Dachau survivors by nationality, the number of prisoners who passed through the Dachau concentration camp, the list of the number of deaths and executions by year, and the composition of the International Prisoners Committee are also included.

Diary of Edgar Kupfer-Koberwitz (Diary of E. K.)

Ten pages of the Dachau report are devoted to a diary that was partially translated from German into English during the writing the report. These are excerpts from the diary of the Dachau survivor Edgar Kupfer-Koberwitz, which he risked his life to write secretly during his imprisonment in the camp from November 1942 to spring 1945. In the diary, Kupfer-Koberwitz recorded his personal experiences and those of his prisoner friends. The excerpts from the diary are meant to illustrate and serve as evidence for crimes committed in the Dachau concentration camp. The CIC Detachment investigators considered this diary to be "one of the most interesting documents" they had obtained on the Dachau crime complex. Because Kupfer-Koberwitz was seen to be at risk of German reprisals, only his initials are given as the author in the Dachau report.[40] Kupfer-Koberwitz, who managed to hide the diary until the camp's liberation, published excerpts from it in 1957 under the title "The Powerful and the Helpless". His unabridged diary was published in 1997, under the title "Dachau Diaries".[41]

Statement by Eleonore Hodys (Statement by E. H.)

The section Statement by E.H. covers 15 pages in the Dachau report (pp. 46 to 60) and is thus the longest thematically continuous section in the report. It contains the testimony of a female concentration camp inmate with the initials E.H., who reports on her experiences in the Auschwitz concentration camp and incriminates members of the SS assigned there. She gave a detailed account of events in the Auschwitz concentration camp and in particular of the violent crimes committed by the SS in the "bunker", the camp prison in Block 11 of the main camp in Auschwitz, where, according to her own statements, she was imprisoned for nine months. Among other things, she stated that after being admitted to the Auschwitz concentration camp, she initially had a privileged position among the prisoners. For example, she had been employed as an embroiderer in the villa of the camp commander Rudolf Höss, where she was well fed and lived in a single room. She also reports that the camp commandant made advances to her. In October 1942 she was locked up in the bunker (Block 11) and initially received preferential treatment there. Along with other members of the Auschwitz camp SS, she also incriminated camp commander Höss. He had secretly visited her in the bunker and had sexual intercourse with her. Höss is said to have impregnated Hodys, whereupon she was taken to a standing cell to die of starvation to cover up the affair.[42][43]

Background and subsequent use

Why the E. H. statement was included in the Dachau report, given it has no connection with the Dachau crime complex, is unclear. The "Statement by E.H." contains the transcript of the testimony of the female prisoner Eleonore Hodys, also known as Nora Mattaliano-Hodys, about her experiences in the Auschwitz concentration camp, as recorded by the SS judge Konrad Morgen in October 1944. Morgen headed an SS commission of internal enquiry that was supposed to uncover and bring to trial corruption in concentration camps in particular. The members of the investigating commission were made aware of Hodys by a member of the SS in the Auschwitz concentration camp who was in custody and had testified as a witness in the proceedings against the former head of the political department in Auschwitz, Max Grabner, before the SS and police court in Weimar. Morgen stated after the end of the war that he had taken Hodys out of the bunker to provide witness protection. Physically weakened and ill, he had her taken to a Munich clinic for convalescence at the end of July 1944, until she could finally be questioned by Morgen in October 1944 about events in the Auschwitz concentration camp.[44]

A copy of this protocol was given to US investigators by Gerhard Wiebeck, who worked under Morgen, immediately after the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp. The Hodys' transcript was translated from German into English and included in the Dachau Report.[45] Wiebeck, who was taken into American internment custody in the course of the liberation of Dachau concentration camp, is also listed with a short vita in the Dachau report.[46] A back-translation of this protocol into German made by Wiebeck also played a role as evidence in the first Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial, on which he provided comprehensive information during his testimony in October 1964.[45] Transcripts of the protocols of Hody's interrogation are kept in the Institute of Contemporary History, Munich and are available in digitalised form.[47]

Reception

British historian Dan Stone considers the report to be one of the first post-war publications on the German concentration camps, which would represent a combination of careful scientific observation and "burning rage" which resulted from the disturbing conditions which were documented photographically.[48]

German historian Ludwig Eiber classifies the US Army report as the "first overview" of the Dachau concentration camp crime complex. However, he believes the report would also contain "some significant errors", because the interrogators would not have distinguished enough the reports of prisoners that applied to Dachau from those that referred to Auschwitz.[49] According to his assessment, the Dachau Report focused on the mass crimes committed in this concentration camp. Eiber cites the report as an example of one of the first post-war publications on the subject. He believes the report set out to document such crimes as to "create a basis for punishment".[50]

Several surviving originals of the report are stored in the library of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.[51]

Furthermore, the report paints a very negative overall picture of the group of "criminal" prisoners. According to the current state of research, the collective stigmatisation of the "criminal" prisoners as helpers of the SS is, however, no longer tenable.[52]

Dachau gas chamber

Under the heading "Executions" on page 33, the report describes a large gas chamber at the camp, which had a capacity of 200 people, in addition to five smaller chambers. It bore the inscription "Brausebad" (shower bath) above the door and inside there were 15 shower heads through which poisonous gas was introduced. The report describes the gassing of unsuspecting prisoners who died within 10 minutes as if this actually took place at Dachau.[53]

The account of gassing prisoners in Dachau is not corroborated in other sources. In fact, the construction of a new crematorium was completed in Dachau in the spring of 1943. Known as "Barrack X", the crematorium had four small chambers for clothing disinfestation using Zyklon B[53] and a larger gas chamber. However, the latter was never used for executions.[54] The only evidence that existed involved plans to use the gas chamber to test combat gases on humans. Whether these experiments, planned by medical doctor and SS member Sigmund Rascher, were in fact carried out is not known as of 2011.[55] Some Holocaust deniers have cited the incorrect reports of gassing at Dachau in order to falsely claim that the Nazis did not systematically exterminate Jews using poison gas at other camps such as Auschwitz–Birkenau.[56]

E. H. statement

The Auschwitz survivor and camp chronicler Hermann Langbein classifies Hody's statements in the report as mixture of "memories with fantasies of an insane person".[57] In addition to incidents that were true, certain details could also be untrue, especially those regarding time. In his view, the protocol should be subjected to a critical review within the framework of a historical evaluation.[58]

2000 republished edition

In July 2000, a new edition of the Dachau report, edited and expanded by Michael Wiley Perry, was published by an American publisher Inkling Books, titled Dachau Liberated: The Official Report by U.S. Seventh Army. The new edition contains the original report including photographs and illustrations, additional edits and commentary by Perry along with sketches made by 2nd Lt. Ted Mackechnie at Dachau on 30 April 1945.[59]

References

- ↑ Hammermann 2004, p. 27f.

- 1 2 3 Hammermann 2004, p. 42.

- ↑ Hammermann 2004, p. 41.

- ↑ Zámečník 2007, p. 390f.

- 1 2 3 Sauvage 2007, p. 63.

- 1 2 McManus 2015, p. 138.

- 1 2 Dachau Report, unnumbered p. 3

- ↑ Schappes 1993, p. 20.

- ↑ Perry 2000, p. 5.

- ↑ Dachau Report, p. 2.

- ↑ Dachau Report, p. 4.

- ↑ Sigel 1992, pp. 16–, 48.

- ↑ Perry 2000, pp. 2, 5.

- ↑ Quinn 1991, End of chapter 34.

- ↑ Perry 2000, p. 2.

- ↑ Frei 1987, p. 381 fn 17.

- ↑ Marcuse 1990, p. 184: "Am 3. Mai traf eine Delegation von 18 US-amerikanischen Chefredakteuren und Verlegern ein. Sie wurden eigens vom amerikanischen Oberkommandierenden Eisenhower nach Europa eingeladen, um durch ihre Berichterstattung die Öffentlichkeit in den USA von dem Ausmaß und der Authentizität der Greuel zu überzeugen"

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 18, 21,

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 35-45, 46-60, 61-63.

- 1 2 Dachau Report, pp. 3, 14, 16.

- ↑ Dachau Report, p. 3, 11

- ↑ Dachau Report, p. 44.

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 5f., 15, 28, 65.

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 6, 66.

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 3, 9, 11-12.

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 31-33, 61.

- ↑ Dachau Report, p. 3, 7–10, 60.

- ↑ Dachau Report, p. 8

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 3-4, 7, 9-10, 12, 19-21, 63

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 7, 9-11, 19-21.

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 10, 20-21.

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 9-10, 19-21.

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 33f.

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 3-6.

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 18, 22.

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 27-30

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 9-10

- ↑ Dachau Report, pp. 30-31,

- ↑ Comite Internationale de Dachau; Barbara Distel, KZ-Gedenkstätte Dachau (ed.): Konzentrationslager Dachau 1933 bis 1945 - Text- und Bilddokumente zur Ausstellung, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-87490-750-3, p. 201.

- ↑ Perry 2000, p. 55 fn 1.

- ↑ Björn Berg: Edgar Kupfer-Koberwitz: Dachauer Tagebücher. The Records of Prisoner 24814 In: Bookmark 1/1998 of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein

- ↑ Langbein 1996, pp. 362f, 461.

- ↑ Dachau Report, p. 46f.

- ↑ Langbein 1996, p. 460.

- 1 2 Transcript of the examination of witness Gerhard Wiebeck on 1 October 1964 during the first Frankfurt Auschwitz trial "Strafsache gegen Mulka u. a.", 4 Ks 2/63. auschwitz-prozess.de

- ↑ Dachau Report, p. 61.

- ↑ Correspondence of Gerhard Wiebeck with the Institute of Contemporary History from 1955 and back-translation of the transcript of Eleonore Hody's testimony from autumn 1944 (inventory number ZS-599)

- ↑ Stone 2015, p. 77.

- ↑ Eiber 2007, p. 37, fn 1.

- ↑ Eiber 2007, p. 12.

- ↑ Alfred L. Howes, 7th. Army: Dachau. Library Call Number: D805.5.D33 D32 1945, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- ↑ Lieske 2016, p. 10f.

- 1 2 Distel 2011, p. 337 fn 2.

- ↑ Distel 2011, p. 338.

- ↑ Distel 2011, p. 339.

- ↑ Altman 2012, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Langbein 1996, p. 461.

- ↑ Langbein 1996, p. 461f.

- ↑ Perry 2000, pp. 6–.

External links

- Dachau at Wikimedia Commons

- Dachau, digitised PDF version with bibliographical references in the online library of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Dachau is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive (with bibliographical references)

Bibliography

- Altman, Andrew (2012). "Freedom of Expression and Human Rights Law: The Case of Holocaust Denial". Speech and Harm: Controversies Over Free Speech. Oxford University Press. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-0-19-174135-7.

- Distel, Barbara (2011). "Die Gaskammer in der "Baracke X" des Konzentrationslagers Dachau". Neue Studien zu nationalsozialistischen Massentötungen durch Giftgas. Metropol-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-940938-99-2.

- Eiber, Ludwig (2007). "Kriminalakte Tatort Konzentrationslager Dachau. Verbrechen im KZ Dachau und Versuche zu ihrer Ahndung bis zum Kriegsende". Dachauer Prozesse – NS-Verbrechen vor amerikanischen Militärgerichten in Dachau 1945–1948. Wallstein Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8353-0167-2.

- Frei, Norbert (1987). ""Wir waren blind, ungläubig und langsam." Buchenwald, Dachau und die amerikanischen Medien im Frühjahr 1945". Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. 35 (3): 385–401. ISSN 0042-5702. JSTOR 30195321.

- Hammermann, Gabriele (2004). "Das Kriegsende in Dachau". Kriegsende 1945. Verbrechen, Katastrophen, Befreiungen in nationaler und internationaler Perspektive. Dachauer Symposien zur Zeitgeschichte. Vol. 4. Wallstein Verlag.

- Langbein, Hermann (1996). Menschen in Auschwitz. Vienna.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lieske, Dagmar (2016). Unbequeme Opfer?: "Berufsverbrecher" als Häftlinge im KZ Sachsenhausen. Forschungsbeiträge und Materialien der Stiftung Brandenburgische Gedenkstätten (in German). Vol. 16. Metropol. ISBN 978-3-86331-297-8.

- Marcuse, Harold (1990). "Das ehemalige Konzentrationslager Dachau: Der mühevolle Weg zur Gedenkstätte, 1945-1968" (PDF). Dachauer Hefte (6): 184.

- McManus, John C. (2015). Hell Before Their Very Eyes: American Soldiers Liberate Concentration Camps in Germany, April 1945. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-4214-1765-3 – via Google Books.

- Schappes, Morris U. (1993). "The Editors Diary: U.S. Army Reports on Dachau 1933-1945". Jewish Currents. Vol. 47. pp. 20–.

- Perry, Michael Wiley (2000). Dachau Liberated: The Official Report by U.S. Seventh Army Released Within Days of the Camp's Liberation by Elements of the 42nd and 45th Divisions. Inkling Books. ISBN 978-1-58742-003-0.

- Quinn, William Wilson (1991). Buffalo Bill Remembers: Truth and Courage. Wilderness Adventure Books. ISBN 978-0-923568-23-8.

- Sauvage, Pierre (2007). "America and the Holocaust". Civil Courage: A Response to Contemporary Conflict and Prejudice. Peter Lang Publishing.

- Sigel, Robert (1992). Im Interesse der Gerechtigkeit. The Dachau War Crimes Trials 1945-1948.

- Stone, Dan (2015). The Liberation of the Camps: The End of the Holocaust and Its Aftermath. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21603-5.

- Zámečník, Stanislav (2007). Comité International de Dachau (ed.). Das war Dachau (in German). Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-596-17228-3.