| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(S)-(β-D-Glucopyranosyloxy)(4-hydroxyphenyl)acetonitrile | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(S)-(4-Hydroxyphenyl){[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxy}acetonitrile | |

| Other names

(S)-4-Hydroxymandelnitrile-β-D-glucopyranoside | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.163 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C14H17NO7 | |

| Molar mass | 311.29 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Dhurrin is a cyanogenic glycoside produced in many plants. Discovered in multiple sorghum varieties in 1906 as the culprit of cattle poisoning by hydrogen cyanide, dhurrin is most typically associated with Sorghum bicolor,[1] the organism used for mapping the biosynthesis of dhurrin from tyrosine. Dhurrin's name is derived from the Arabic word for sorghum.

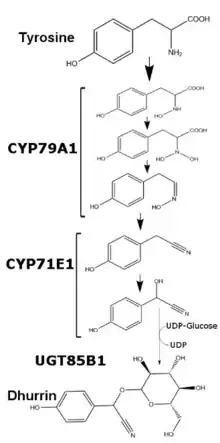

Biosynthesis

Regulation in Sorghum bicolor

In Sorghum bicolor, dhurrin production is regulated at the transcriptional level and varies depending on the plant’s age and available nutrients. Dhurrin content within S. bicolor can be correlated to the amount of mRNA and translated protein of enzymes CYP79A1 and CYP71E1, two membrane bound members of the cytochrome P450 superfamily. While transcription and translation of these two enzymes is relatively higher for the first few days of growth, transcription is greatly reduced past one week of growth. After five weeks of growth, transcription and translation of both enzymes in the leaves becomes undetectable, while stems in said plants maintain the minimal production of both enzymes. With the addition of excess nitrate, transcription of both enzymes increases, though not to the levels seen in early development.[2] The last enzyme in dhurrin synthesis, UGT85B1, is a soluble enzyme which exchanges glucose from UDP-glucose to the aglycone of dhurrin and forms the glycosidic bond.

Transgenic synthesis

Addition of both CYP79A1 and CYP71E1 into the genomes of Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum has been shown to be sufficient for Dhurrin production to occur.[3] Both of these enzymes are sufficient and necessary for Dhurrin production, as removal of the CYP79A1 gene from the Sorghum bicolor genome results in plants lacking dhurrin content. This strain could theoretically be used as a safer crop for fodder in arid environments where sorghum is the only available grain. In vitro biosynthesis of dhurrin has been constructed in both microsomes recovered from Sorghum bicolor seedlings and in micelles.[4]

Toxicity

Mammals

Mammalian intestines contain multiple glucosidases which efficiently hydrolyze glycosidic bonds. Upon hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond, the aglycone of dhurrin rapidly degrades to form hydrogen cyanide which is then absorbed into the bloodstream. Lethal dosage of dhurrin in humans and other mammals is theoretically high as one molecule of hydrogen cyanide is produced per molecule of dhurrin. Content of dhurrin by mass in sorghum is relatively low with respect to overall plant matter. As such, it would require a human to eat a considerably large amount of raw sorghum before experiencing adverse effects. In arid environments, sorghum is the best option for cereal grain and fodder as it can withstand extreme drought conditions.[5] Animals consuming the raw sorghum as fodder are much more likely to eat an amount that would contain a lethal dosage of dhurrin for their respective species and can result in animal loss due to hydrogen cyanide poisoning.

As an insect repellent

In response to external damage to the stem, sorghum varieties can release dhurrin at the damage site. This response has been shown to repel insects as transgenic sorghum made unable to produce dhurrin was heavily favored by herbivorous insects when compared to wild-type sorghum varieties.[6]

References

- ↑ Blyth, Alexander Wynter (May 13, 2013). Poisons: Their Effects and Detection A Manual for the Use of Analytical Chemists and Experts. USA: Charles Griffin and Company. p. 204.

- ↑ Busk, Peter Kamp (July 2002). "Dhurrin Synthesis in Sorghum Is Regulated at the Transcriptional Level and Induced by Nitrogen Fertilization in Older Plants". Plant Physiology. 129 (3): 1222–1231. doi:10.1104/pp.000687. PMC 166516. PMID 12114576.

- ↑ Bak, Soren (August 2000). "Transgenic Tobacco and Arabidopsis Plants Expressing the Two Multifunctional Sorghum Cytochrome P450 Enzymes, CYP79A1 and CYP71E1, Are Cyanogenic and Accumulate Metabolites Derived from Intermediates in Dhurrin Biosynthesis". Plant Physiology. 123 (4): 1437–1448. doi:10.1104/pp.123.4.1437. PMC 59100. PMID 10938360.

- ↑ Kahn, R A (December 1997). "Isolation and reconstitution of cytochrome P450ox and in vitro reconstitution of the entire biosynthetic pathway of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin from sorghum". Plant Physiology. 115 (4): 1661–1670. doi:10.1104/pp.115.4.1661. PMC 158632. PMID 9414567.

- ↑ Borrell, Andrew K. (2014). "Drought adaptation of stay-green sorghum is associated with canopy development, leaf anatomy, root growth, and water uptake". Journal of Experimental Botany. 65 (21): 6251–6263. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru232. PMC 4223986. PMID 25381433.

- ↑ Krothapalli, Kartikeya (October 2013). "Forward Genetics by Genome Sequencing Reveals That Rapid Cyanide Release Deters Insect Herbivory of Sorghum Bicolor". Genetics. 195 (2): 309–318. doi:10.1534/genetics.113.149567. PMC 3781961. PMID 23893483.