Diego de Rebolledo | |

|---|---|

| Royal Governor of La Florida | |

| In office June 18, 1654 – February 20, 1659 | |

| Preceded by | Pedro Benedit Horruytiner |

| Succeeded by | Alonso de Aranguiz y Cortés |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Unknown |

| Died | Unknown |

| Profession | Administrator (Governor of Florida) |

Diego de Rebolledo y Suárez de Aponte, was the 21st colonial governor of Spanish Florida (La Florida), in office from June 18, 1654 to February 20, 1659.[1] He is considered by historians to be one of the more controversial governors of Spanish colonial Florida. Rebolledo showed a marked lack of respect for the status of the Timucua chiefs as hereditary leaders and administrative intermediaries, an attitude that provoked a Timucuan uprising against Spanish rule. Rebolledo was a Knight of the Order of Santiago.[2]

Governor of Florida

Diego de Rebolledo, the son of a former royal treasurer of Cartagena, Spain, was appointed governor of the Spanish province of La Florida on March 24, 1653, and began his term on June 18, 1654, at Saint Augustine, the capital of the province.[3][4] Food was scarce in Florida and prices were high during Rebolledo's administration, which circumstance benefited the governor directly. Contemporary documents indicate that Rebolledo sold wine and chocolate, among other items, at high prices to the local inhabitants.[5]

Relations with the Indians

Rebolledo had little experience in colonial government when he arrived in Florida,[4] and paid no heed to established customs regarding the distribution of gifts to the chiefs of the Indian mission towns in the province, thus disrespecting the native peoples' cultural expectation of gifts in return for their allegiance.[3] Because the Timucuan towns had no products that he could sell at a good price to the Havana market, Rebolledo refused to offer them the customary gifts, The acquisitive governor did, however, offer those Indian leaders who had deerskins or other salable commodities as many gifts as available governmental funds from the royal subsidy, or situado, could subsidize.[6]

Royal treasurer Joseph de Prado took measures to assert his control of the King's alms to the Indians, the gasto de indios, and in December 1654, sent a letter to the Spanish Crown explaining that Rebolledo must cease this commercial activity and that the clothes given to the Indian chiefs should be donated out of the royal stores. Prado maintained that gifts should be distributed only by the quartermaster and should be independent of the treasurer's account in order to control costs. Nevertheless, Rebolledo asserted that the governor should oversee the distribution of gifts and that if he neglected to provide them, the Indians might rebel.

The fiscal, i.e., the royal attorney-general, of the Consejo de Indias (Council of the Indies) ruled in favor of Prado in 1656, finding that Rebolledo engaged in illegal activities to enrich himself during his administration, and exploited the Indians as well as the Spanish soldiers stationed in Florida. Rebollero bought goods in Havana and developed a barter trade with the Indians of South Florida, trading iron tools and other goods in exchange for amber which he sold in Havana,[7] even paying the royal taxes. Thus the traditional diplomacy of giving presents to establish relationships with the various tribes was replaced by a commerce that personally benefited the governor. A royal inquiry noted in 1660 that Rebolledo had refused to offer a visiting chieftain the customary reception, and neglected to follow custom and invite him to dinner at the governor's.[8] The former provincial governor, Pedro Benedit Horruytiner, criticized Rebollero for dealing only with the Indians of the coast, saying that he should offer gifts to all the Indian chiefs.

Timucuan Revolt

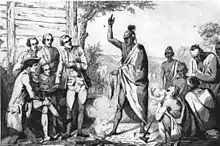

When Rebolledo got news from the king in April 1656 of the British seizure of Jamaica the previous May; the king warned that they would next attack Florida, and ordered the activation of the Indian militias, summoning five hundred Indians from the Guale, Apalachee and Timucuan towns to help defend the Presidio of St. Augustine.[9][6][8] St. Augustine suffered a food shortage in 1656; consequently, Rebolledo ordered that each of the Timucua and Apalachee tribesmen, including their principal men, carry 75 pounds of maize to the city. This was a gross insult to the dignity of the Indian leaders, who refused to porter such loads like commoners or slaves.[6][10][8] The Indian chiefs complained to the Franciscans of this treatment by the governor, and protested having to share their people's food supplies, which were already precarious since their lands had poor soil, and of the requirement to carry the grain over the long distance between their territory and St. Augustine.[11] The Timucua chiefs were so outraged that they organized a revolt against the Spanish in 1656. Unlike during previous Indian uprisings, no Franciscans were killed.

Governor Rebolledo led an expedition of Spanish troops and Indian warriors from Guale against the Timucua revolt to pacify the region,[3] and after the capture of those Timucuan chiefs who had revolted, traveled to Ivitachuco to oversee their trial. On November 27, six caciques and four Timucuan warriors were sentenced to death.[12][10]

Other Spanish settlements in Florida

In 1656, the Spanish moved their Mission San Luis de Apalachee to the second highest hill in what is now Tallahassee. The chief of the native village at the site of the old San Luis, who desired to maintain his alliance with the Spanish, agreed to move his village also. The garrison was expanded to 12 soldiers, and the chief promised to build a substantial casa fuerte, or blockhouse, for them. Although Rebolledo planned for further expansion of the garrison and building a regular fort, Apalachee opposition to the project stalled it for well over a generation. The blockhouse at San Luis was described in 1675 by Bishop Calderón as a "fortified country house."[13]

In 1657, Governor Rebolledo ordered the removal of Indians from the remote towns of Ybica and Oconi to repopulate Mission Nombre de Dios, located at the spot where Pedro Menéndez landed when he founded St. Augustine. Its Indian inhabitants had tended the fields of the presidio until a large percentage of them died in a smallpox epidemic.[14][10] Rebelledo created an Indian militia and distributed the warriors in the interior and along the coast to defend against English assaults. These were deployed several times as a complement to the Spanish infantry. The Franciscans complained that Rebolledo, rather than seeking their counsel regarding relations with the Indians, summoned them only when he had already made a decision.[3]

Religious policies

Rebolledo wanted St. Augustine to become an Episcopal see, or at least an apostolic vicariate, so that the sacrament of confirmation (without which many people in Florida had died) might be conferred on Catholics in the province. In 1655, the King of Spain and the Council of the Indies (Consejo de Indias) asked the Archbishop of Santo Domingo, the Bishop of Cuba, and the governor of Havana, among others, their opinion on the matter.[15] Though the petition to erect St. Augustine into a bishopric went to Rome, the matter was never taken up, and Florida remained part of the Diocese of Santiago de Cuba until 1709. Although Rebolledo obtained the approval of the Council for Saint Augustine's erection, the city did not become an Episcopal seat.[16]

On February 20, 1659, Rebolledo finished his term as governor of Florida, and was succeeded by Alonso de Aranguiz y Cortés.[1]

References

- 1 2 John Worth. "The Governors of Colonial Florida, 1565-1821". uwf.edu. University of West Florida. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ John E. Worth (4 February 2007). The Struggle for the Georgia Coast. University of Alabama Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8173-5411-4.

- 1 2 3 4 John E. Worth (1998). The Timucuan Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida: Resistance and Destruction. Vol. 2. University Press of Florida. pp. 39–97. ISBN 978-0-8130-1575-0.

- 1 2 Linda Suzanne Cecelia Borgen. Master's thesis. (2007). "Timucuan Prelude to Rebellion: Diego de Rebolledo vs. Lucas Menendez in Mid-17th Century Spanish Florida" (PDF). Pensacola, Florida: University of West Florida. p. 51. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ↑ El Fuerte de Piedra y la Villa (in English: The Stone Fort and the Village). Page 93.

- 1 2 3 Joseph M. Hall, Jr. (13 December 2012). Zamumo's Gifts: Indian-European Exchange in the Colonial Southeast. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-8122-2223-4.

- ↑ John. H. Hann (1986), "Translation of Governor Rebolledo's 1657 Visitation of Three Florida Provinces and Related Documents", Florida Archaeology 2, Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research, p. 136

- 1 2 3 Robert C. Galgano (2005). Feast of Souls: Indians and Spaniards in the Seventeenth-century Missions of Florida and New Mexico. UNM Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-8263-3648-4.

- ↑ S. Hooper, Kevin (2006). The Early History of Clay County: A Wilderness that Could be Tamed. The History Press. Page 31.

- 1 2 3 Paul E. Hoffman (11 January 2002), Florida's Frontiers, Indiana University Press, pp. 128–131, ISBN 0-253-10878-0

- ↑ Fred Lamar Pearson (1983). "Timucuan Rebellion of 1656: The Rebolledo Investigation and the Civil-Religious Controversy". The Florida Historical Quarterly. The Florida Historical Society. 61 (3): 260–280. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Linda Suzanne Cecelia Borgen. Master's thesis. (2007). "Timucuan Prelude to Rebellion: Diego de Rebolledo vs. Lucas Menendez in Mid-17th Century Spanish Florida" (PDF). Pensacola, Florida: University of West Florida. p. 4. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ↑ John H. Hann (1 January 1990), Summary Guide to Spanish Florida Missions and Visitas, Academy of American Franciscan History, p. 70, ISBN 9780883822852

- ↑ Alejandra Dubcovsky (4 April 2016). Informed Power. Harvard University Press. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-0-674-96880-6.

- ↑ John Gilmary Shea (1886). The Catholic church. Рипол Классик. p. 165. ISBN 978-5-87800-365-0.

- ↑ Thompson, George Alexander; Arrowsmith, Aaron; De Alcedo, Antonio (June 5, 2011). The Geographical and Historical Dictionary of America and the West Indies, Volumen 2. Page 104.