Dominant white (W)[1][2] is a group of genetically related coat color alleles on the KIT gene of the horse, best known for producing an all-white coat, but also able to produce various forms of white spotting, as well as bold white markings. Prior to the discovery of the W allelic series, many of these patterns were described by the term sabino, which is still used by some breed registries.

White-colored horses are born with unpigmented pink skin and white hair, usually with dark eyes. Under normal conditions, at least one parent must be dominant white to produce dominant white offspring. However, most of the currently-known alleles can be linked to a documented spontaneous mutation that began with a single ancestor born of non-dominant white parents. Horses that exhibit white spotting will have pink skin under the white markings, but usually have dark skin beneath any dark hair.

There are many different alleles that produce dominant white or white spotting; as of 2022 they are labeled W1 through W28 and W30 through W35, plus the first W allele discovered was named Sabino 1 (SB-1) instead of W1.[3][4][5] They are associated with the KIT gene.[B] The white spotting produced can range from white markings like those made by W20, to the irregularly-shaped or roaning patterns previously described as Sabino, to a fully white or almost fully white horse.

For many of the W alleles, the white coats are, as the name suggests, inherited dominantly,[D] meaning that a horse only needs one copy of the allele to have a white or white spotted coat. In fact, some such alleles may be embryonic lethal when homozygous. Others, such as SB-1 and W20, are incomplete dominants, capable of producing viable offspring with two copies of the gene, and who generally have more white than horses with only one copy. In addition, different alleles which on their own give a white-spotted but not completely white horse, such as W5 and W10, can combine to make a horse completely white.

White can occur in any breed, and has been studied in many different breeds. Because of the wide range of patterns produced, some suggest the family be called “white spotting” rather than “white.” Other researchers suggest the term "dominant white" be used only for the W alleles thought to be embryonic lethal when homozygous.[6]

White is both genetically and visually distinct from gray and cremello. Dominant white is not the same as lethal white syndrome, nor are white horses "albinos"—Tyrosinase negative albinism has never been documented in horses.

Description

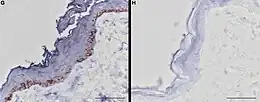

Although the term "dominant white" is typically associated with a pure white coat, such horses may be all-white, near-white, partially white, or exhibit an irregular spotting pattern similar to that of sabino horses.[7] To add to the confusion, at least some horses in each of those groups might be referred to as "dominant white", "white spotted", or "sabino". The amount of white hair depends on which KIT alleles are involved.[8] At birth, most of the white hair is rooted in unpigmented pink skin. The pink skin lacks melanocytes, and appears pink from the underlying network of capillaries. White spotting is not known to affect eye color, and most white horses have brown eyes.[9]

White or near-white

White horses are born with pink skin and a white coat, which they retain throughout their lives.[10] The genetic factors that produce an all-white horse are often also capable of producing a near-white horse, which is mostly white but has some areas that are pigmented normally. Near-white horses most commonly have color in the hair and skin along the topline (dorsal midline) of the horse, in the mane, and on the ears.[7] The color is often interspersed as specks or spots on a white background. In addition, the hooves are usually white, but may have striping if there is pigmented skin on the coronary band just above the hoof.[11][12] In some cases, foals born with residual non-white hair may lose some or all of this pigment with age, without the help of the gray factor.[13]

White spotting

White spotting from a W allele is difficult to identify visually, as it can range from small white markings in the case of a heterozygous W20 horse all the way to an obvious pinto pattern. In addition, even completely white horses can have genes which by themselves would only give white spotting, such as W20 combined with W22[2] or W5 combined with W10. As such, the only reliable way to find out whether a horse has one of the known white spotting patterns from an allele on KIT is to have it genetically tested.

Prevalence

Dominant white is one of several potential genetic causes for horses with near-white or completely white coats; it may occur through spontaneous mutation, and thus may be found unexpectedly in any breed, even those that discourage excessive white markings. To date, forms of dominant white have been identified in Thoroughbreds,[13] Standardbreds,[14] American Quarter Horses,[7] Frederiksborg horses,[7] Icelandic horses,[7] Shetland ponies,[13] Franches Montagnes horses,[13] South German Draft horses,[7] and the Arabian horse.[13] The American White Horse, which is descended primarily from one white stallion crossed on non-white mares, is known for its white coat, as is the Camarillo White Horse.[15][16]

Inheritance

The W locus was mapped to the KIT gene in 2007.[13] KIT is short for "KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase".[17] White spotting is caused by multiple forms, or alleles, of the KIT gene.[13] All horses possess the KIT gene, as it is necessary for survival even at the earliest stages of development. The presence or absence of dominant white is based on the presence of certain altered variants of KIT. Each unique form is called an allele, and for every trait, all animals inherit one allele from each parent. The original or "normal" form of KIT, which is expected in horses without dominant white spotting, is called the "wild type" allele.[A] Thus, a dominant white horse has at least one KIT allele with a mutation associated with dominant white spotting.

Allelic series

The KIT gene contains over 2000 base pairs, and a change in any of those base pairs results in a mutant allele.[7] Over forty seven such alleles have been identified by sequencing the KIT genes of various horses.[7] The resultant phenotype of many of these alleles is not yet known, but over 30 have been linked to white spotting.[18][8][19] DNA tests can identify if a horse carries the identified W alleles.

- SB-1 (Sabino 1) was first identified in 2005. The allele was designated with "SB" in an attempt to align with traditional equine coat color terminology. It is located on the KIT gene and is a single nucleotide polymorphism designated KI16+1037A. The mutation results in the skipping of exon 17.When heterozygous, it creates a distinctive white spotting pattern of irregular, rough-edged white patches that usually include two or more white feet or legs, a blaze, spots or roaning on the belly or flanks, and jagged margins to white markings. Homozygous foals are typically at least 90% white-coated at birth, and sometimes termed "Sabino-White."[20]

- W1 was the second KIT allele found to be involved in horse coat color. The researchers who discovered W1-4 decided to name them "W" following the convention in mice, rather than continuing the "SB" series. W1 is found in Franches Montagnes horses descended from a white mare named Cigale born in 1957. Cigale's parents' coats were not extensively marked.[13] A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), a type of mutation in which a single nucleotide is accidentally exchanged for another, is thought to have occurred with Cigale. This mutation (c.2151C>G) is predicted to truncate the protein in the middle of the tyrosine kinase domain, which would severely affect the function of KIT.[13] It is a nonsense mutation located on exon 15 of KIT.[8] Some horses with the W1 mutation are born pure white, but many have residual pigment along the topline, which they may then lose over time. Based on studies of KIT mutations in mice, the severity of this mutation suggests that it may be nonviable in the homozygous state.[21] However, horses with the W1 mutation have been found to have normal blood parameters and do not suffer from anemia.[22]

- W2 is found in Thoroughbred horses descended from KY Colonel, a stallion born in 1946. While KY Colonel was described as a chestnut with extensive white markings, he is known for siring a family of pure white horses through his white daughter, White Beauty, born in 1963.[23] His son War Colors was registered as roan because he had some spots of color, but later became white.[24] The W2 allele is linked to a single nucleotide polymorphism (c.1960G>A),[13] a missense mutation where a glycine is replaced with arginine (p.G654R) in the protein kinase domain, located on exon 17.[8]

- W3 is found in Arabian horses descended from R Khasper, a near-white stallion born in 1996. Neither of his parents were white, and the causative mutation (c.706A>T) is thought to have originated with this horse. It is a nonsense mutation on exon 4, predicted to truncate the protein in the extracellular domain.[13][8] Horses with the W3 allele often retain interspersed flecks or regions of pigmented skin and hair, which may fade with time.[23] Some members of this family possess blue eyes, but these are thought to be inherited separately from the white coat.[23] Based on similar studies in mice, researchers have named W3 as potentially homozygous nonviable.[21]

- W4 is found in Camarillo White Horses, a breed characterized by a white coat, beginning with a spontaneous white stallion born in 1912 named Sultan.[13] Like W1 and W3, these horses may be pure white or near-white, with pigmented areas along the topline that fade with time.[23] This mutation is an SNP (c.1805C>T) which produces a missense mutation replacing alanine with valine in the kinase domain, on exon 12.[13][8]

.jpg.webp)

- W5 is found in Thoroughbreds descending from Puchilingui,[25] a 1984 stallion with sabino-like white spotting and roaning.[7] Horses with the W5 allele exhibit a huge range in white phenotype: a few have been pure white or near-white, while others have sabino-like spotting limited to high, irregular stockings and blazes that covered the face. Twenty-two members of this family were studied, and the 12 with some degree of white spotting were found to have a deletion in exon 15 (p.T732QfsX9),[7] in the form of a frameshift mutation.[8] A later study found that the members of this family with the greatest depigmentation were compound heterozygotes who also carried the W20 allele.[26]

- W6 is found in one near-white Thoroughbred named Marumatsu Live born to non-white parents in 2004.[4] The potential range of expressivity, therefore, is not yet known. The mutation (c.856G>A) is thought to have occurred spontaneously in this horse.[7] It is a missense mutation on exon 5.[8]

- W7 is found in another near-white Thoroughbred named Turf Club[4] born in 2005 to a dam that had nine other offspring, all non-white. The dam did not possess the W7 allele, which results from a splice site mutation (c.338-1G>C),[7] located on intron 2 of KIT.[8]

- W8 was found in an Icelandic horse with sabino-like white spotting, mottling, and roaning, named Þokkadís vom Rosenhof.[4] Both parents and four maternal half-siblings, all non-white, were found without the W8 allele. The W8 allele is also a splice site mutation (c.2222-1G>A),[7] located on intron 15.[8]

- W9 was found in an all-white Holsteiner horse with a single nucleotide polymorphism (c.1789G>A). No relatives were studied, but both parents are non-white.[7] It is a missense mutation on exon 12.[8]

- W10 was found in a study of 27 horses in a family of American Quarter Horses, 10 of which were white or spotted and 17 that were solid and non-white. The 10 family members with W10 had a frameshifting deletion in exon 7 (c.1126_1129delGAAC). Like W5, a wide range of phenotypes were observed. The most modestly marked had large amounts of white on the face and legs and some medium-sized belly spots, while another was nearly all-white.[7][8][27] The founder of this line was GQ Santana, foaled in 2000.[25]

- W11 is found in a family of South German Coldbloods descending from a single white stallion, in which the causative mutation is thought to have originated. The stallion is suspected to be Schimmel, foaled in 1997.[4][27] The mutation responsible for the W11 phenotype is a splice site mutation of intron 20 (c.2684+1G>A).[7]

- W12 was found in a single Thoroughbred colt, about half white, who both was born and died in 2010. The mutation is a deletion mutation found on exon 3.[8][28]

- W13 causes a fully white phenotype, and appears to be homozygous lethal. It was first found in a family Quarter Horse and Paso Peruviano crossbreds, and since has been seen in multiple horse and pony breeds, including some not descended from Quarter horse ancestors.[27] [29][30][31] The cause is a splice site mutation on intron 17.[8][29]

- W14 is a deletion mutation on exon 17, found in Thoroughbreds.[8] The founder is suspected to be Shirayukihime, born in 1996.[4][33] Horses with this mutation are usually fully white but may have some spots of color.

- W15 is found in Arabians, and is a missense mutation on exon 10.[8] The founder is suspected to be Khartoon Khlassic, born in 1996. Horses heterozygous for W15 tend to be partially white, while homozygotes are fully white.[27]

- W16 is found in the Oldenburger and is a missense mutation on exon 18.[8] The three horses studied looked like roany sabinos or near whites, and the founder is suspected to be Celene, born in 2003.

- W17 is found in a Japanese Draft horse and is a pair of missense mutations[34] on exon 14.[8] The horse studied was white with one brown eye and one blue eye.[29]

- W18 is a splice site mutation on intron 8 (c.1346 +1G>A) found in a bay Swiss Warmblood named Colorina von Hoff, who had extensive speckling. Both parents were solid-colored and had no extended head or leg markings.[4][26]

- W19 was found in three part-Arabians with bald face markings, white leg markings extending above the knees and hocks, and irregular belly spots. All three horses tested negative for sabino-1, frame overo and splashed white. W19 is a missense mutation on exon 8 (c.1322A.G; p.Tur41Cys).[26] The founder is suspected to be Fantasia Vu, born in 1990.[35] W19 causes a bald face, extensive leg white, and belly spots. One horse has tested as W19/W19, indicating this allele is likely not homozygous lethal. However, all W19/W19 have presented at birth as max white and all that have been tested at maturity have been sterile. In Europe this was confirmed with extensive testing [36]

- W20 is associated with bold face and leg markings, and can greatly increase the amount of white when combined with certain other white patterns. The W20 sequence was first discovered in 2007, but was not recognized for its effect on coat color until 2013. Horses with one copy of W5 or W22 combined with one copy of W20 tend to be white or nearly all white.[26][37] W20 on its own does tend towards adding white.[38]

- W20 has been found in many breeds including the German Riding Pony, German Warmblood, Thoroughbred, Oldenburger, Welsh pony, Quarter horse, Paint horse, Appaloosa, Noriker, Old-Tori, Gypsy horse, Morgan horse, Clydesdale horse, Franches-Montagnes, Marwari horse, South German Draft, Paso Peruano, Camarillo White Horse, and Hanoverian horse.[39]

- W20 is a missense mutation on exon 14 (c.2045G>A; p.Arg682His).[26]

- W21 is a single nucleotide deletion found in Icelandics.[1] The founder is Ellert frá Baldurshaga, who has a mostly white face with speckles and irregular patches of white across his body. The color has been named "ýruskjóttur".[40][41][42]

- W22 is a deletion thought to have originated in the Thoroughbred mare Not Quite White, born in 1989. She passed it to her two foals Airdrie Apache and Spotted Lady. On its own, W22 is sabino-like, but when paired with W20, it gives a completely white horse.[2][43]

- W23 was found in the white Arabian stallion Boomori Simply Stunning, who had two white foals Meadowview Ivory and Just a Dream. However, the line appears to have died out.[4][44]

- W24 is a mutation that disrupts splicing of KIT. The founder is a white Trottatore Italiano named Via Lattea, born in 2014.[14]

- W25 is a missense mutation on exon 4. The founder is suspected to be the Australian Thoroughbred mare Laughyoumay. She has had one pure white foal with blue eyes, who also carries frame, and one near-white colt with some color on and around the ears.[45][30]

- W26 is a single base pair deletion suspected to have originated with the Australian Thoroughbred mare Marbrowell, born in 1997.[46][30]

- W27 is a missense mutation thought to originate with the Australian Thoroughbred mare Milady Fair. Most horses with this mutation are descended from her great-grand-colt, Colorful Gambler, who has an extensive sabino-like pattern.[4][47][30]

- W28 is a deletion found in a German Riding Pony.[48]

- W29 has not been assigned.

- W30 is found in a family of Berber horses. It is a missense mutation identical to the second missense mutation in W17. The horses with W30 are white or almost fully white.[34]

- W31 traces to an American Quarter Horse stallion, Cookin Merada. It leads to an early stop on the KIT protein sequence, truncating the protein.[19]

- W32 was found in a family of American Paint Horses, and seems to have a mild effect leading to high white on the limbs, belly spots and white facial markings. It is unclear whether the SNP described is actually the causative mutation, or merely linked to it.[19]

- W33 is a de novo variant found in a Standardbred horse that results in sabino-like white spotting.[49]

- W34 is a missense mutation linked to increased white spotting, found in multiple breeds including the American Paint Horse, American Quarter Horse, Appaloosa, Arabian, Mangalarga, Morgan, Mustang, Rocky Mountain horse and some Warmblood breeds.[50]

- W35 is associated with more white than is usually seen on Quarter horses. Researchers found a mutation in the untranslated region on the 5' side of KIT that correlates with the increased white, but it may only be a nearby marker rather than the actual cause. This variant is also called "Holiday" after the horse in which it was discovered. Some horses are homozygous for the marker.[51][52]

- Classic Roan is associated with the KIT gene.[53][54]

- Tobiano is caused by an inversion starting about 100 kb downstream of KIT,[55] and is also considered an allele of KIT.[18]

These alleles do not account for all dominantly inherited white spotting in horses. More KIT alleles are expected to be found with roles in white spotting.[7] Most W alleles occur within a specific breed or family and arise as spontaneous mutations. KIT appears to be prone to mutation, in part due to its many exons, so new alleles of W can occur in any breed.[8] There are likely many KIT variants in the global horse population that have not yet been investigated.

Relation to sabino

Sabino can refer either specifically to Sabino 1 (SB1) or to a variety of visually similar spotting patterns. SB1 creates a nearly pure white horse when homozygous, and bold spotting when heterozygous. To add to the confusion, white spotting created by several W alleles, such as W5, W15, and W19 creates patterns that historically were called sabino. For that reason, the use of the word "sabino" is evolving. Genetically, Sabino 1 is simply another allele on KIT,[20] and thus can be classified in the same “family” of KIT mutations as the alleles labeled W or dominant white.[56]

In its homozygous form, Sabino 1 can be confused with dominant white alleles such as W1, W2, W3, or W4 that create a white or near-white horse with only one copy. Both dominant white and "Sabino-White" horses are identified by all-white or near-white coats with underlying pink skin and dark eyes, often with residual pigment along the dorsal midline. However, it takes two copies of Sabino 1 to produce a Sabino-white horse, and Sabino 1 is not homozygous lethal.[57]

Initially, dominant white was separated from sabino on the grounds that the former had to be entirely white, while the latter could possess some pigment.[58] However, the 2007 and 2009 studies of dominant white showed that many dominant white alleles produce a range of white phenotypes that include horses with pigmented spots in their hair and skin.[7] Each of the larger families of dominant white studied included pure-white horses, horses described as having "sabino-like" white markings, as well as white horses described as "maximal sabino".[7][13]

More recently, dominant white and sabino were distinguished from one another on the grounds that dominant white alleles produce nonviable embryos in the homozygous state, while Sabino 1 was viable when homozygous.[59] However, not all KIT alleles currently identified as "dominant white" have been proven lethal,[21] and in fact W20 is known to be viable in the homozygous form.[60]

The similarities between Dominant White and Sabino 1 reflect their common molecular origin: The W series and SB1 have both been mapped to KIT. The researchers who mapped Sabino 1 in 2005 suggested that other sabino-like patterns might also map to KIT,[20] which has been the case for many other alleles discovered since that time, including major alleles for white leg and facial markings that have also been mapped to or near to the KIT gene.[61]

Molecular genetics

The KIT gene encodes a protein called steel factor receptor, which is critical to the differentiation of stem cells into blood cells, sperm cells, and pigment cells. A process called alternative splicing, which uses the information encoded in the KIT gene to make slightly different proteins (isoforms) for use in different circumstances, may impact whether a mutation on KIT affects blood cells, sperm cells, or pigment cells. Steel factor receptor interacts chemically with steel factor or stem cell factor to relay chemical messages. These messages are used during embryonic development to signal the migration of early melanocytes (pigment cells) from the neural crest tissue to their eventual destinations in the dermal layer. The neural crest is a transient tissue in the embryo that lies along the dorsal line. Melanocytes migrate along the dorsal line to a number of specific sites: near the eye, near the ear, and the top of the head; six sites along each side of the body, and a few along the tail. At these sites, the cells undergo a few rounds of replication and differentiation, and then migrate down and around the body from the dorsal aspect towards the ventral aspect and the limb buds.[62]

The timing of this migration is critical; all white markings, from a small star to a pure white coat, are caused by the failed migration of melanocytes.[61]

A certain degree of the eventual amount of white, and its "design", is completely random. The development of an organism from single-celled to fully formed is a process with many, many steps. Even beginning with identical genomes, as in clones and identical twins, the process is unlikely to occur the same way twice. A process with this element of randomness is called a stochastic process, and cell differentiation is, in part, a stochastic process.[63] The stochastic element of development is partly responsible for the eventual appearance of white on a horse, potentially accounting for nearly a quarter of the phenotype.[64] The research team that studied dominant white cited "subtle variations in the amount of residual KIT protein" as a potential cause for the variability in phenotype of horses with the same allele. They also speculated that variability in the phenotype of horses with W1 might be caused by "different efficacies of [nonsense-mediated decay] in different individuals and in different body regions." That is, some horses destroy more of the mutant KIT protein than others.[7]

Lethality

Early embryonal lethality, also known as early embryonic death or a non-viable embryo, may occur when the embryo possesses two copies of certain dominant white alleles.[65] The reason for this is that several mutations of W are caused by nonsense mutations, frameshift mutations or DNA deletions, which, if homozygous, would make it impossible to produce a functional KIT protein. However, it appears that not all W alleles are embryonic lethals. Homozygous embryos from alleles of certain missense and splice site mutations are sometimes viable, apparently because they have less effect on gene function.[8] For instance, W1 is a nonsense mutation and it is thought that horses with the genotype W1/W1 would die in utero, while W20 is a missense mutation and living horses with the W20/W20 genotype have been found. A 2013 study also located horses that were compound W5/W20 heterozygotes, almost completely white, essentially with greater depigmentation than could be accounted for by either allele alone.[26]

"White" horses that are not dominant white

White horses are potent symbols in many cultures.[66] An array of horse coat colors may be identified as "white", often inaccurately, and many are genetically distinct from "dominant white".

"Albino" horses have never been documented, despite references to so-called "albino" horses.[67][68] Dominant white is caused by the absence of pigment cells (melanocytes), whereas albino animals have a normal distribution of melanocytes.[69] Also, a diagnosis of albinism in humans is based on visual impairment, which has not been described in horses with dominant white nor similar coat colors.[70] In other mammals, the diagnosis of albinism is based on the impairment of tyrosinase production.[71] No mutations of the tyrosinase gene are known in horses, however, cream and pearl colors result from mutations to a protein involved in tyrosinase transport.[72]

Non-white colors

- Cremello or Blue-eyed cream horses have rosy pink skin,[73] pale blue eyes and cream-colored coats, indicating that pigment cells and pigment are present in the skin, eyes, and coat, but at lower levels.[74] White horses do not have pigment cells, and thus no pigment, in the skin or coat. In addition, dominant white horses seldom have blue eyes.[9] Other genetic factors, or combinations of genetic factors, such as the pearl gene or champagne gene, can also produce cremello-like coats. These coat colors may be distinguishable from dominant white by their unusually colored eyes.[75]

- Gray horses are born any color and progressively replace their colored coat with gray and white hairs. Most gray horses have dark skin, unless they happen to also carry genes for pink or unpigmented skin. Unlike white horses, grays are not born white, nor is their skin color affected by their coat color change.[76]

- Leopard complex horses, such as the Appaloosa and Knabstrupper breeds, are genetically quite distinct from all other white spotting patterns. The fewspot leopard pattern, however, can resemble white. Two factors influence the eventual appearance of a leopard complex coat: whether one copy or two copies of the Leopard alleles are present, and the degree of dense leopard-associated white patterning that is present at birth.[77] If a foal is homozygous for the LP allele and has extensive dense white patterning, they will appear nearly white at birth, and may continue to lighten with age. In other parts of the world, these horses are called "white born."[78][79] "White born" foals are less common among Appaloosa horses, which tend to have blankets and varnish roans, than Knabstruppers or Norikers, which tend to be full leopards.[80]

- Tovero, Medicine hat or War bonnet are terms sometimes applied to Pinto horses with residual non-white areas only around the head, especially the ears and poll, while most of the remaining coat is white.[81] While dominant white horses may have areas of residual pigment only around the ears and poll, the term "medicine hat" usually refers to horses with more commonly known white spotting genes, most often tobiano, combined with frame overo, sabino or splashed white.[82]

Lethal white overo

Foals with lethal white syndrome (LWS) have two copies of the frame overo gene and are born with white or nearly white coats and pink skin. However, unlike dominant white horses, foals with LWS are born with an underdeveloped colon that is untreatable, and if not euthanized, invariably die of colic within a few days of birth.[83] Horses that carry only one allele of the LWS gene are healthy and typically exhibit the "frame overo" spotting pattern. In cases of "solid" horses with frame overo ancestry, uncertain "overo" (non-tobiano) phenotype, or horses with multiple patterns, the LWS allele can be detected by DNA test.[84]

Mosaicism

Mosaicism in horses is thought to account for some spontaneous occurrences of white, near-white, spotted, and roan horses.[85] Mosaicism refers to mutations that occur after the single-cell stage, and therefore affect only a portion of the adult cells.[86] Mosaicism may be one possible cause for the rare occurrence of brindle coloring in horses.[87] Mosaic-white horses would be visually indistinguishable from dominant whites. Mosaicism could produce white or partially white foals if a stem cell in the developing foal underwent a mutation, or change to the DNA, that resulted in unpigmented skin and hair. The cells that descend from the affected stem cell will exhibit the mutation, while the rest of the cells are unaffected.

A mosaic mutation may or may not be inheritable, depending on the cell populations affected.[88] Though this is not always the case, genetic mutations can occur spontaneously in one sex cell of a parent during gametogenesis.[89] In these cases, called germline mutations, the mutation will be present in the single-celled zygote conceived from the affected sperm or egg cell, and the condition can be inherited by the next generation.[85]

History of dominant white research

Dominant white horses were first described in scientific literature in 1912. Horse breeder William P. Newell described his family of white and near-white horses to researcher A. P. Sturtevant of Columbia University:

"The colour of skin is white or so-called pink, usually with a few small dark specks in skin. Some have a great many dark spots in skin. These latter usually have a few dark stripes in hoofs; otherwise the hoofs are almost invariably white. Those that do not have dark specks in skin usually have glass or watch eyes, otherwise dark eyes ... I have one colt coming one year old that is pure white, not a coloured speck on him, not a coloured hair on him, and with glass [blue] eyes."[12]

Sturtevant and his contemporaries agreed that this colt's blue eyes were inherited separately from his white coat.[90] In 1912, Sturtevant assigned the "white" trait to the White or W locus.[12] At the time there was no means of assigning W to a position on the chromosome, or to a gene.

This family of white horses produced Old King in 1908, a dark-eyed white stallion that was purchased by Caleb R. and Hudson B. Thompson. Old King was bred to Morgan mares to produce a breed of horse known today as the American White Horse.[15] A grandson of Old King, Snow King, was at the center of the first major study of the dominant white coat color in horses, conducted in 1969 by Dr. William L. Pulos of Alfred University and Dr. Frederick B. Hutt of Cornell. They concluded, based on test matings and progeny phenotype ratios, that the white coat was dominantly inherited and embryonic lethal in the homozygous state.[91] Other factors, such as variations in expressivity and the influence of multiple genes, may have influenced the progeny ratios that Pulos and Hutt observed.[92] The white coat of the American White Horse has not yet been mapped.

A 1924 study by C. Wriedt identified a heritable white coat color in the Frederiksborg horse.[93] Wriedt described a range of what he considered to be homozygote phenotypes: all-white, white with pigmented flecks, or weißgraue, which transliterates to "white-gray."[94] The German term for gray horse is schimmel, not weißgraue.[95] Heterozygotes, according to Wriedt, ranged from roaned or diluted to more or less solid white horses. Reviewers, such as Miguel Odriozola, reinterpreted Wriedt's data in successive years, while Pulos and Hutt felt that his work had been "erroneous" because Wriedt never concluded that white was lethal when homozygous.[96]

Other researchers prior to modern DNA analysis developed remarkably prescient theories. The gene itself was first proposed and named W in 1948.[8] In a 1969 work on horse coat colors, A los colores del caballo, Miguel Odriozola suggested that various forms of dominantly inherited white spotting might be arranged sequentially along one chromosome, thus allowing for the varied expression of dominant white. He also proposed that other, distant genes might also influence the amount of white present.[97]

The embryonic lethality hypothesis was originally supported by Pulos and Hutt's 1969 study of Mendelian progeny ratios.[10] Conclusions about Mendelian traits that are controlled by a single gene can be drawn from test breedings with large sample sizes. However, traits that are controlled by allelic series or multiple loci are not Mendelian characters, and may not be subject to Mendelian ratios.[98]

Pulos and Hutt knew that if the allele that created a white coat was recessive, then white horses would have to be homozygous for the condition and therefore breeding white horses together would always result in a white foal. However, this did not occur in their study and they concluded that white was not recessive. Conversely, if a white coat was a simple autosomal dominant, ww horses would be non-white, while both Ww and WW horses would be white, and the latter would always produce white offspring. But Pulos and Hutt did not observe any white horses that always produced white offspring, suggesting that homozygous dominant (WW) white horses did not exist. As a result, Pulos and Hutt concluded that white was semidominant and lethal in the homozygous state: ww horses were non-white, Ww were white, and WW died.[99]

Pulos and Hutt reported that neonatal death rates in white foals were similar to those in non-white foals, and concluded that homozygous white fetuses died during gestation.[100] No aborted fetuses were found, suggesting that death occurred early on in embryonic or fetal development and that the fetus was "resorbed."[101]

Prior to Pulos and Hutt's work, researchers were split on the mode of inheritance of white and whether it was deleterious (harmful).[102] Recent research has discovered several possible genetic pathways to a white coat, so disparities in these historical findings may reflect the action of different genes. It is also possible that the varied origins of Pulos and Hutt's white horses might be responsible for the lack of homozygotes. It now appears that not all equine dominant white mutations cause embryonic lethality in the homozygous state.[92]

The white (W) locus was first recognized in mice in 1908.[104] The mutation of the same name produces a belly spot and interspersed white hairs on the dorsal aspect of the coat in the heterozygote (W/+) and black-eyed white in the homozygote (W/W). While heterozygotes are healthy, homozygous W mice have severe macrocytic anemia and die within days.[105] A mutation which affects multiple systems is "pleiotropic." Following the mapping of the KIT gene to the W locus in 1988, researchers began identifying other mutations as part of an allelic series of W.[106] There are dozens of known alleles, each representing a unique mutation on the KIT gene, which primarily produce white spotting from tiny head spots to fully white coats, macrocytic anemia from mild to lethal, and sterility.[105] Some alleles, such as splash produce white spotting alone, while others affect the health of the animal even in the heterozygous state. Alleles encoding small amounts of white are no more likely to be linked with anemia and sterility than those encoding conspicuous white. Presently, no anecdotal or research evidence has suggested that equine KIT mutations affect health or fertility.[107] A recent study showed that blood parameters in horses with the W1 mutation were normal.[22]

Between the time of Pulos and Hutt's study in 1969 and the beginning of molecular-level research into dominant white in the 21st century, a pattern known as "Sabino" began to describe certain white phenotypes.[108] The first allele of the W series identified by researchers was an incomplete dominant that was named Sabino-1 (SB-1). It is found on the same locus as other W alleles. When homozygous, SB-1 can produce nearly all-white horses.

In 2007, researchers from Switzerland and the United States published a paper identifying the genetic cause of dominant white spotting in horses from the Franches Montagnes horse, Camarillo White Horse, Arabian horse and Thoroughbred breeds.[13] Each of these dominant white conditions had occurred separately and spontaneously in the past 75 years, and each represents a different allele (variation or form) of the same gene. These same researchers identified a further seven unique causes of dominant white in 2009: three in distinct families of Thoroughbreds, one Icelandic horse, one Holsteiner, a large family of American Quarter Horses and a family of South German Draft horses.[7]

Homologous conditions

In humans, a skin condition called piebaldism is caused by more than a dozen distinct mutations in the KIT gene. Piebaldism in humans is characterized by a white forelock, and pigmentless patches of skin on the forehead, brow, face, ventral trunk and extremities. Outside of pigmentation, piebaldism is an otherwise benign condition.[109] In pigs, the "patch," "belted," and commercial "white" colors are caused by mutations on the KIT gene.[110] The best-known model for KIT gene function is the mouse, in which over 90 alleles have been described. The various alleles produce everything from white toes and blazes to black-eyed white mice, panda-white to sashed and belted. Many of these alleles are lethal in the homozygous state, lethal when combined, or sublethal due to anemia. Male mice with KIT mutations are often sterile.[111]

Notes

- ^ Use of the term "wild type" is subjective, as genes undergo changes, called mutation, at statistically regular intervals called mutation rates.

- ^ A gene is a unit of heredity which encodes the instructions to make molecules.[112] An allele is a specific version of a gene.[113] Geneticists often discuss only two alleles at a time: the "wildtype" or normal allele which encodes the correct molecule, and the mutant allele. When more than two alleles are known, they form an allelic series. A locus is the physical location of a gene on a chromosome.[113]

- ^ For any particular gene, when an individual inherits two identical alleles, one from each parent, it is homozygous, or a homozygote. When an individual inherits two different alleles, one from each parent, it is heterozygous or a heterozygote.[113]

- ^ Mendelian traits are characteristics of an organism that are controlled by a single gene. Mendelian traits can be described as dominant if the characteristic is found in heterozygotes, or recessive if not. Dominance and recessiveness are properties of traits, not genes. Defining a trait as dominant (the word dominate is a verb) or recessive depends on how the trait is defined.[114]

References

- 1 2 Haase, Bianca; Jagannathan, Vidhya; Rieder, Stefan; Leeb, Tosso (2015). "A novel KIT variant in an Icelandic horse with white-spotted coat color". Animal Genetics. 46 (4): 466. doi:10.1111/age.12313. PMID 26059442.

- 1 2 3 Dürig; Jude; Holl; Brooks; Lafayette; Jagannathan; Leeb (April 26, 2017). "Whole genome sequencing reveals a novel deletion variant in the KIT gene in horses with white spotted coat colour phenotypes". Animal Genetics. 48 (4): 483–485. doi:10.1111/age.12556. PMID 28444912.

- ↑ "W variants with associated breeds". etalondx.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "W variants with associated breeds". Centerforanimalgenetics.com.

- ↑ "OMIA - Online Mendelian Inheritance in Animals". www.omia.org. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- ↑ Sponenberg, D. Phillip; Bellone, Rebecca (2017). "7. Nonsymmetric Patches of White: White Marks, Paints, and Pintos". Equine Color Genetics (4 ed.). Wiley Blackwell. p. 194.

In its strictest sense, dominant white is reserved for those KIT alleles thought to be lethal to homozygous embryos.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Haase B, Brooks SA, Tozaki T, et al. (October 2009). "Seven novel KIT mutations in horses with white coat colour phenotypes". Animal Genetics. 40 (5): 623–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2009.01893.x. PMID 19456317.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Bailey, Ernest; Brooks, Samantha A. (2013). Horse genetics (2. ed.). Wallingford: CABI. pp. 56–59. ISBN 9781780643298.

- 1 2 Haase B, Brooks SA, Schlumbaum A, et al. (November 2007). "Allelic heterogeneity at the equine KIT locus in dominant white (W) horses". PLOS Genetics. 3 (11): e195. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030195. PMC 2065884. PMID 17997609.

Eyes are normally pigmented in dominant white horses, probably due to the different origin of the retinal melanocytes, which develop from local neuroectoderm and not from the neural crest, as do the skin melanocytes.

- 1 2 Pulos WL, Hutt FB (1969). "Lethal dominant white in horses". The Journal of Heredity. 60 (2): 59–63. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a107933. PMID 5816567.

- ↑ Pulos, WL; FB Hutt (1969). "Lethal Dominant White in Horses". Journal of Heredity. 60 (2): 59–63. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a107933. PMID 5816567.

- 1 2 3 Sturtevant, AH (1912). "A critical examination of recent studies on coat colour inheritance in horses" (PDF). Journal of Genetics. 2 (1): 41–51. doi:10.1007/BF02981546. S2CID 40604153.

"The colour of skin is white or so-called pink, usually with a few small dark specks in skin. Some have a great many dark spots in skin. These latter usually have a few dark stripes in hoofs; otherwise the hoofs are almost invariably white. Those that do not have dark specks in skin usually have glass or watch eyes, otherwise dark eyes ... I have one colt coming one year old that is pure white, not a coloured speck on him, not a coloured hair on him, and with glass eyes." [WP Newell] The term "glass eye" means a white eye. Therefore the colt described above is almost an albino in appearance. However, his sire is one of the dark-eyed somewhat spotted whites, his dam being a brown Trotter. Since "glass" eyes occur not infrequently in pigmented horses it seems probable that this white-eyed albino (?) is really an extreme case of spotting, plus an entirely independent "glass" eye. Mr Newell writes that white mated to white gives about 50% white to 50% pigmented. He reports only three matings of white to white. The results of these were, one white, one roan, and one gray.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Haase B, Brooks SA, Schlumbaum A, et al. (November 2007). "Allelic heterogeneity at the equine KIT locus in dominant white (W) horses". PLOS Genetics. 3 (11): e195. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030195. PMC 2065884. PMID 17997609.

- 1 2 Capomaccio, Stefano; Milanesi, Marco; Nocelli, Cristina; Giontella, Andrea; Verini-Supplizi, Andrea; Branca, Michele; Silvestrelli, Maurizio; Cappelli, Katia (2017-08-30). "Splicing site disruption in the KIT gene as strong candidate for white dominant phenotype in an Italian Trotter". Animal Genetics. 48 (6): 727–728. doi:10.1111/age.12590. ISSN 0268-9146. PMID 28856698. S2CID 28616314.

- 1 2 "American Creme and White". Breeds of Livestock. Oklahoma State University. 1999-05-03. Archived from the original on 2009-12-09. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ "Camarillo White Horse Association (CWHA)". Camarillo White Horse Association. 2009-03-17. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ↑ "Nomenclature History, Kit". Mouse Genome Informatics. The Jackson Laboratory. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- 1 2 Henkel J, Lafayette C, Brooks SA, Martin K, Patterson-Rosa L, Cook D, Jagannathan V, Leeb T (2019). "Whole-genome sequencing reveals a large deletion in the MITF gene in horses with white spotted coat colour and increased risk of deafness" (PDF). Animal Genetics. 50 (2): 172–174. doi:10.1111/age.12762. PMID 30644113. S2CID 58656314.

- 1 2 3 Patterson Rosa, Laura (July 5, 2021). "Two Variants of KIT Causing White Patterning in Stock-Type Horses". Journal of Heredity. 112 (5): 447–451. doi:10.1093/jhered/esab033. PMID 34223905. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 Brooks, Samantha; Ernest Bailey (2005). "Exon skipping in the KIT gene causes a Sabino spotting pattern in horses". Mammalian Genome. 16 (11): 893–902. doi:10.1007/s00335-005-2472-y. PMID 16284805. S2CID 32782072.

Chapter 3

- 1 2 3 Haase, B. et al (2007) "While [homozygous lethality] is certainly likely for the two nonsense mutations found in Franches-Montagnes Horses and Arabians, it should not necessarily be assumed for the two reported missense mutations or for any of the other as-yet unknown W mutations."

- 1 2 Haase, B; Obexer-Ruff G; Dolf G; Rieder S; Burger D; Poncet PA; Gerber V; Howard J; Leeb T (9 April 2009). "Haematological parameters are normal in dominant white Franches-Montagnes horses carrying a KIT mutation". Veterinary Journal. 184 (3): 315–7. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.02.017. PMID 19362501.

- 1 2 3 4 Castle, Nancy (2009-05-19). "Equine KIT Gene Mutations" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-30. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ "War Colors". Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- 1 2 "Dominant White - Equine Testing - Animal Genetics". Animalgenetics.us. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hauswirth, Regula; Jude, Rony; Haase, Bianca; Bellone, Rebecca R.; Archer, Sheila; Holl, Heather; Brooks, Samantha A.; Tozaki, Teruaki; Penedo, Maria Cecilia T.; Rieder, Stefan; Leeb, Tosso (December 2013). "Novel variants in the KIT and PAX3 genes in horses with white-spotted coat colour phenotypes". Animal Genetics. 44 (6): 763–765. doi:10.1111/age.12057. PMID 23659293. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "More about Dominant White". Etalon Diagnostics. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ↑ Holl, H.; Brooks, S.; Bailey, E. (2010-11-10). "De novo mutation of KIT discovered as a result of a non-hereditary white coat colour pattern". Animal Genetics. 41: 196–198. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2010.02135.x. ISSN 0268-9146.

- 1 2 3 Haase B, Rieder S, Tozaki T, Hasegawa T, Penedo CT, Jude R, Leeb T (23 February 2011). "Five novel KIT mutations in horses with white coat colour phenotypes". Animal Genetics. 42 (3): 337–340. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2011.02173.x. PMID 21554354.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoban, Rhiarn; Castle, Kao; Hamilton, Natasha; Haase, Bianca (2018-01-15). "Novel KIT variants for dominant white in the Australian horse population". Animal Genetics. 49 (1): 99–100. doi:10.1111/age.12627. ISSN 0268-9146. PMID 29333746.

- ↑ Esdaile, Elizabeth; Kallenberg, Angelica; Avila, Felipe; Bellone, Rebecca R. (2021). "Identification of W13 in the American Miniature Horse and Shetland Pony Populations". Genes. 12 (12): 1985. doi:10.3390/genes12121985. PMC 8702037. PMID 34946933.

- ↑ "Buchiko". Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ↑ "Shirayukihime". Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- 1 2 Martin, Katie; Patterson Rosa, Laura; Vierra, Micaela; Foster, Gabriel; Brooks, Samantha A.; Lafayette, Christa (2021). "De novo mutation of KIT causes extensive coat white patterning in a family of Berber horses". Animal Genetics. 52 (1): 135–137. doi:10.1111/age.13017. PMID 33111383. S2CID 225100025.

- ↑ "Fantasia Vu". Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ↑ "Meet "Hello Colordream"". Etalon Diagnostics. July 18, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ↑ "Dominant White Mutations – W5, W10, W20, and W22". Retrieved 27 Feb 2022.

- ↑ Brooks, S. A.; Palermo, K. M.; Kahn, A.; Hein, J. (2020). "Impact of white-spotting alleles, including W20, on phenotype in the American Paint Horse". Animal Genetics. 51 (5): 707–715. doi:10.1111/age.12960. PMID 32686191. S2CID 220655602.

- ↑ Hauswirth, Regula; Jude, Rony; Haase, Bianca; Bellone, Rebecca R.; Archer, Sheila; Holl, Heather; Brooks, Samantha A.; Tozaki, Teruaki; Penedo, Maria Cecilia T.; Rieder, Stefan; Leeb, Tosso (2013). "Novel variants in the KIT and PAX3 genes in horses with white-spotted coat colour phenotypes" (PDF). Animal Genetics. 44 (6): 763–765. doi:10.1111/age.12057. PMID 23659293.

- ↑ "New coat colour in the Icelandic horse".

- ↑ Bianca Britton. "New coat color pattern found in Icelandic horse". CNN. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ↑ "New unique colour variant in Icelandic horse has appeared". Iceland Monitor. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ↑ "practical horse genetics - inherited traits in horses". Practicalhorsegenetics.com.au. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ↑ "AmberShade Stables: Color genetics: Hey, look, more dominant white!". 2018-08-22.

- ↑ "practical horse genetics - inherited traits in horses". Practicalhorsegenetics.com.au. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ↑ "practical horse genetics - inherited traits in horses". Practicalhorsegenetics.com.au. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ↑ "Practical horse genetics - inherited traits in horses". Practicalhorsegenetics.com.au.

- ↑ Hug; Jude; Henkel; Jagannathan; Leeb (2019). "A novel KIT deletion variant in a German Riding Pony with white‐spotting coat colour phenotype" (PDF). Animal Genetics. 50 (6): 761–763. doi:10.1111/age.12840. PMID 31463981. S2CID 201665263.

- ↑ Esdaile, Elizabeth; Till, Brad; Kallenberg, Angelica; Fremeux, Michelle; Bickel, Leslie; Bellone, Rebecca R. (2022-05-31). "A de novo missense mutation in KIT is responsible for dominant white spotting phenotype in a Standardbred horse". Animal Genetics. 53 (4): 534–537. doi:10.1111/age.13222. ISSN 0268-9146. PMID 35641888. S2CID 249233588.

- ↑ Patterson Rosa, Laura; Martin, Katie; Vierra, Micaela; Lundquist, Erica; Foster, Gabriel; Brooks, Samantha A.; Lafayette, Christa (January 2022). "A KIT Variant Associated with Increased White Spotting Epistatic to MC1R Genotype in Horses (Equus caballus)". Animals. 12 (15): 1958. doi:10.3390/ani12151958. PMC 9367399. PMID 35953947.

- ↑ "Etalon Discovers New White Marking Variant W35 "Holiday" in Horses".

- ↑ McFadden, A.; Martin, K.; Foster, G.; Vierra, M.; Lundquist, E. W.; Everts, R. E.; Martin, E.; Volz, E.; McLoone, K.; Brooks, S. A.; Lafayette, C. (2023). "5'UTR Variant in KIT Associated With White Spotting in Horses". Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 127: 104563. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2023.104563. PMID 37182614.

- ↑ Grilz-Seger, Gertrud; Reiter, Simone; Neuditschko, Markus; Wallner, Barbara; Rieder, Stefan; Leeb, Tosso; Jagannathan, Vidhya; Mesarič, Matjaz; Cotman, Markus; Pausch, Hubert; Lindgren, Gabriella; Velie, Brandon; Horna, Michaela; Brem, Gottfried; Druml, Thomas (2020). "A Genome-Wide Association Analysis in Noriker Horses Identifies a SNP Associated With Roan Coat Color". Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 88: 102950. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2020.102950. PMID 32303326. S2CID 212861746.

- ↑ Voß, Katharina; Tetens, Julia; Thaller, Georg; Becker, Doreen (2020). "Coat Color Roan Shows Association with KIT Variants and No Evidence of Lethality in Icelandic Horses". Genes. 11 (6): 680. doi:10.3390/genes11060680. PMC 7348759. PMID 32580410.

- ↑ Brooks; Lear; Adelson; Bailey (2007). "A chromosome inversion near the KIT gene and the Tobiano spotting pattern in horses". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 119 (3–4): 225–30. doi:10.1159/000112065. PMID 18253033. S2CID 22835035.

- ↑ "Sabino-1". Centerforanimalgenetics.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ↑ UC Davis. "Sabino 1". Veterinary Genetics Laboratory. University of California - Davis. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

Horses with 2 copies of the Sabino1 gene, are at least 90% white and are referred to as Sabino-white.

- ↑ Castle, Nancy (2009). "It has been the belief of horse enthusiasts that true “white” horses were always completely white with no retained pigment, and that if a horse retained some pigment of the skin and/or hair, it was genetically some form of sabino if it were not the result of other known white spotting patterns (tobiano, frame overo, splash white, etc.)"

- ↑ Castle, Nancy (2009). "KIT mutations that cause depigmentation generally ranging from approximately 50% depigmented to all white phenotypes, and are also predicted to be embryonic lethal when homozygous, are classified as Dominant White. Mutations that are viable in the homozygous state are categorized as Sabino."

- ↑ "Dominant White - Horse Coat Color".

- 1 2 Rieder S, Hagger C, Obexer-Ruff G, Leeb T, Poncet PA (2008). "Genetic analysis of white facial and leg markings in the Swiss Franches-Montagnes Horse Breed". The Journal of Heredity. 99 (2): 130–6. doi:10.1093/jhered/esm115. PMID 18296388.

Phenotypes may vary from tiny depigmentated body spots to white head and leg markings, further on to large white spotting and finally nearly complete depigmentation in white-born horses ... White markings result from the lack of melanocytes in the hair follicles and the skin ... A completely pigmented head or leg depends on the complete migration and clonal proliferation of the melanoblasts in the mesoderm of the developing fetus, thus ensuring that limbs and the head acquire a full complement of melanocytes

- ↑ Thiruvenkadan, AK; N Kandasamy; S Panneerselvam (2008). "Review: Coat colour inheritance in horses". Livestock Science. 117 (2–3): 109–129. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2008.05.008.

During embryogenesis the pigment cells (melanocytes) migrate to specific sites on either side of the body as well as the backline. There are three such sites on the head (near the eye, ear, and top of the head), and six sites along each side of the body, and several along the tail. A few pigment cells migrate to each of these sites, there they proliferate and migrate outwards, joining up to form larger patches, spreading down the legs and down the head until they meet up under the chin, and down the body until they meet up on the belly (Cattanach, 1999).

- ↑ Kurakin A (January 2005). "Self-organization vs Watchmaker: stochastic gene expression and cell differentiation". Development Genes and Evolution. 215 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1007/s00427-004-0448-7. PMID 15645318. S2CID 10728304.

- ↑ Woolf CM (1995). "Influence of stochastic events on the phenotypic variation of common white leg markings in the Arabian horse: implications for various genetic disorders in humans". The Journal of Heredity. 86 (2): 129–35. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111542. PMID 7751597.

- ↑ Haase, B. et al. (2007) "In one study, white horses were shown to be obligate heterozygous (W/+), as the W/W genotype was hypothesized to cause early embryonal lethality [4]."

- ↑ Cooper, JC (1978). "Horse". An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Traditional Symbols. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 85–6. ISBN 978-0-500-27125-4.

... [T]he white horse ... represents pure intellect; the unblemished; innocence; life and light, and is ridden by heroes.

- ↑ Castle, William E (1948). "The ABC of Color Inheritance in Horses". Genetics. 33 (1): 22–35. doi:10.1093/genetics/33.1.22. PMC 1209395. PMID 17247268.

No true albino mutation of the color gene is known among horses, though several varieties of white horse are popularly known as albinos.

- ↑ O'Hara, Mary (1941). My Friend Flicka. Lippincott. ISBN 978-0-06-080902-7.

- ↑ Silvers, Willys K. (1979). "3: The b-Locus and c (Albino) Series of Alleles". The Coat Colors of Mice: A Model for Mammalian Gene Action and Interaction. Springer Verlag. p. 59. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

... the inability of albino animals to produce pigment stems not from an absence of melanocytes

- ↑ "What is Albinism?". The National Organization for Albinism and Hypopigmentation. Archived from the original on 2012-05-14. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ Cheville, Norman F (August 2006). Introduction to veterinary pathology (3 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-8138-2495-6.

Albinism results from a structural gene mutation at the locus that codes for tyrosinase; that is, albino animals have a genetically determined failure of tyrosine synthesis.

- ↑ Wijesen; Schmutz (May–June 2015). "A Missense Mutation in SLC45A2 Is Associated with Albinism in Several Small Long Haired Dog Breeds". Journal of Heredity. 106 (3): 285–8. doi:10.1093/jhered/esv008. PMID 25790827.

- ↑ "Facts and Myths". Cream Gene Information. Cremello and Perlino Education Association. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ↑ Mariat, Denis; Sead Taourit; Gérard Guérin (2003). "A mutation in the MATP gene causes the cream coat colour in the horse". Genet. Sel. Evol. 35 (1): 119–133. doi:10.1051/gse:2002039. PMC 2732686. PMID 12605854.

- ↑ "Champagne-Cream Combinations". International Champagne Horse Registry. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ Rosengren Pielberg G, Golovko A, Sundström E, et al. (August 2008). "A cis-acting regulatory mutation causes premature hair graying and susceptibility to melanoma in the horse". Nature Genetics. 40 (8): 1004–9. doi:10.1038/ng.185. PMID 18641652. S2CID 6666394.

- ↑ Bellone, Rebecca R; Samantha A Brookers; Lynne Sandmeyer; Barbara A Murphy; George Forsyth; Sheila Archer; Ernest Bailey; Bruce Grahn (August 2008). "Differential Gene Expression of TRPM1, the Potential Cause of Congenital Stationary Night Blindness and Coat Spotting Patterns (LP) in the Appaloosa Horse (Equus caballus)". Genetics. 179 (4): 1861–1870. doi:10.1534/genetics.108.088807. PMC 2516064. PMID 18660533.

A single autosomal dominant gene, leopard complex (LP), is thought to be responsible for the inheritance of these patterns and associated traits, while modifier genes are thought to play a role in determining the amount of white patterning that is inherited (Miller 1965; Sponenberg et al. 1990; S. Archer and R. R. Bellone, unpublished data)

- ↑ "Rules & Knabstrupper Breed Standard of the German ZfDP Registry". UK Knabstrupper Association. Archived from the original on 2009-05-29. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ "Die Farbmerkmale" (in German). Knabstrupper.de. Archived from the original on 2009-06-18. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ Sponenberg, Dan Phillip (2003). "5. Patterns Characterized by Patches of White". Equine color genetics (2 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8138-0759-1.

... most Appaloosas have a blanket or varnish roan phenotype ... In the Noriker breed most horses with LpLp are leopard, and the few varnish roans or blanketed horses in the breed tend to produce leopards more than their own blanket or varnish roan pattern

- ↑ Vrotsos, Paul D.; Elizabeth M. Santschi; James R. Mickelson (2001). "The Impact of the Mutation Causing Overo Lethal White Syndrome on White Patterning in Horses". Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the AAEP. 47: 385–391.

This is a rare color pattern in which the coat is almost entirely white (Fig. 6). Pigmented areas are found primarily on the ears and poll, but may also appear on the thorax, flank, dorsal midline, and tail head. Medicine hat horses can arise from overo or tovero bloodlines; when of overo bloodlines, medicine hat horses may have pigment that is quite faint on the dorsal midline.

- ↑ Janet Piercy (2001). "Breed Close Up Part II". The Colorful World of Paints & Pintos. International Registry of Colored Horses. Archived from the original on 2009-02-24. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

The perfectly marked medicine hat is usually a tovero, but these horses can be overos and tobianos too

- ↑ Metallinos, DL; Bowling AT; Rine J (June 1998). "A missense mutation in the endothelin-B receptor gene is associated with Lethal White Foal Syndrome: an equine version of Hirschsprung Disease". Mammalian Genome. 9 (6): 426–31. doi:10.1007/s003359900790. PMID 9585428. S2CID 19536624.

- ↑ "Equine Coat Color Tests". Veterinary Genetics Laboratory. UC Davis. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- 1 2 Haase, B. et al (2009). "Whenever a white foal is born out of solid-coloured parents, the most likely explanation is a KIT mutation in the germline of one of its parents or alternatively a mutation in the early developing embryo itself, which might lead to mosaic foals."

- ↑ Strachan, Tom & Read, Andrew (1999) [1996]. "Genes in pedigrees: 3.2 Complications to the basic pedigree patterns". In Kingston, Fran (ed.). Human Molecular Genetics. BIOS Scientific Publishers (2 ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-85996-202-2. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

Post-zygotic mutations produce mosaics with two (or more) genetically distinct cell lines. [...] Mutations occurring in a parent's germ line can cause de novo inherited disease in a child. When an early germ-line mutation has produced a person who harbors a large clone of mutant germ-line cells (germinal, or gonadal, mosaicism), a normal couple with no previous family history may produce more than one child with the same serious dominant disease

- ↑ Kay L. Isaac. "Brindle Information". American Brindle Equine Association. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

One only outwardly appearing brindle that is likely the result of a mosaic or chimeric equine ...

- ↑ Haase, B. et al (2009) "our study included several founder animals where mosaicism cannot be excluded. One example for such a scenario is the W8 allele observed in a single "mottled" Icelandic horse, which represents the founder animal for this mutation (Fig. 1g). This horse might be a mosaic, and it remains to be determined whether it will consistently produce offspring with the mottled phenotype."

- ↑ Strachan, Tom & Andrew Read (1999) "A common assumption is that an entirely normal person produces a single mutant gamete. However, this is not necessarily what happens. Unless there is something special about the mutational process, such that it can happen only during gametogenesis, mutations may arise at any time during post-zygotic life."

- ↑ Sturtevant, AH (1912). "Since "glass" eyes occur not infrequently in pigmented horses it seems probable that this white-eyed albino [sic] is really an extreme case of spotting, plus an entirely independent "glass" eye."

- ↑ Pulos, WL; FB Hutt (1969). "Lethal Dominant White in Horses". Journal of Heredity. 60 (2): 59–63. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a107933. PMID 5816567.

- 1 2 Haase, B. et al (2007). "However, this report on the embryonic lethality was derived from the analysis of offspring phenotype ratios in a single herd segregating one or more unknown mutations."

- ↑ Wriedt, C (1924). "Vererbungsfaktoren bei weissen Pferden im Gestut Fredriksborg". Zeitschrift für Tierzuchtung und Zuchtungsbiologie. 1 (2): 231–242. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0388.1924.tb00195.x.

- ↑ WL Pulos & FB Hutt (1969). "Although Wriedt referred to Sturtevant's report in his genetic analysis of records of the Frederiksborg white horses, he considered the latter to be recessive whites, with homozygotes white, white with gray spots, or gray white ("weissgraue"). Heterozygotes were believed to vary all the way from dilute gray to full color."

- ↑ Beth Mead (2005-09-09). "International Horse & Pony Colour Term Dictionary Online (Part 2)". Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ↑ WL Pulos & FB Hutt (1969). "In the light of more recent evidence, these conclusions now seem to have been erroneous ..."

- ↑ WL Pulos & FB Hutt (1969). "Odriozola added no new data on dominant white, but ... suggested that different forms of W arranged linearly in the chromosome might be responsible for the differing degrees of white ... and that the expression of white is also influenced by modifying genes."

- ↑ Strachan, Tom & Read, Andrew (1999) [1996]. "Genes in pedigrees: 3.4 Nonmendelian characters". In Kingston, Fran (ed.). Human Molecular Genetics. BIOS Scientific Publishers (2 ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 333. ISBN 978-1-85996-202-2. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- ↑ Pulos & Hutt (1969). "Each of the five white stallions used in the stud sired one or more colored foals. Similarly, all of the eight white mares that were adequately tested produced at least one colored foal. The fact that these 13 white horses were all proven to be heterozygotes agrees with previous reports that white horses with colored eyes did not breed true to type, but always produced some colored progeny. This, in turn, suggests that the genoytpe WW is not viable."

- ↑ Pulos & Hutt (1969). "Among six white foals (from parents both white) that died soon after birth, one had been unable to stand and nurse; death of another was attributed to exposure, one was strangled and another killed by the mare. The possibility that any of these might have been homozygotes is refuted by the fact that similar conditions caused death of several foals from the colored pony mares. Some of those foals were white, and some colored, but none could have been WW."

- ↑ Pulos & Hutt (1969). "As aborted foetuses were not found although a constant watch was maintained for them, it is possible that the homozygotes die early in gestation and are resorbed."

- ↑ Pulos & Hutt (1969). "... in his genetic analysis of records of the Frederiksborg white horses, [Wriedt] considered [them] to be recessive whites, with homozygotes white, white with gray spots, or gray white ("weissgraue") ... He considered that the gene for white could not itself be lethal because four fertile white mares produced from 46 matings a total of 37 foals, none of which was dead or weak, and that good record (80 percent fertility) was better than could have been expected if the gene for white color were lethal. Subsequently von Lehmann-Mathildenhoh reported evidence of a dominant white in the Bellschwitz and Ruschof studs ... He did not consider the possibility that it might be associated with any lethal action ... [Salisbury] made no reference to effects of the gene in homozygotes ... Berge lists dominant white horses as heterozygotes, and follows Castle in suggesting that homozygosity for W is lethal."

- ↑ "Yukichan Horse Pedigree". www.pedigreequery.com. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ↑ Durham, F.M. A preliminary account of the inheritance of coat colour in mice. Reports to the Evolution Committee IV: 41-53, 1908.

- 1 2 Silvers, Willys K. (1979). "10: Dominant Spotting, Patch, and Rump-White". The Coat Colors of Mice: A Model for Mammalian Gene Action and Interaction. Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-90367-5. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ↑ Chabot, Benoit; Dennis A. Stephenson; Verne M. Chapman; Peter Besmer; Alan Bernstein (1988-09-01). "The proto-oncogene c-kit encoding a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor maps to the mouse W locus". Nature. 335 (6185): 88–9. Bibcode:1988Natur.335...88C. doi:10.1038/335088a0. PMID 2457811. S2CID 4344521.

- ↑ Haase, B. et al (2009). "Currently, there is little known about possible pleiotropic effects of KIT mutations in horses."

- ↑ "Sabino". Equine Color. Archived from the original on 2008-12-25. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- ↑ Michael D. Fox; Camila K. Janniger (2009-01-30). "Piebaldism". eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ Pielberg G, Olsson C, Syvänen AC, Andersson L (January 2002). "Unexpectedly high allelic diversity at the KIT locus causing dominant white color in the domestic pig". Genetics. 160 (1): 305–11. doi:10.1093/genetics/160.1.305. PMC 1461930. PMID 11805065.

- ↑ Silvers, Willys K. (1979). The Coat Colors of Mice. Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-90367-5.

- ↑ "Handbook: Cells and DNA: What is a gene?". Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2009-06-26. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- 1 2 3 In: GeneTests: Medical Genetics Information Resource (database online). Educational Materials: Glossary. Copyright, University of Washington, Seattle. 1993-2009. Available at http://www.genetests.org. Accessed 2009-07-11.

- ↑ Strachan, Tom & Read, Andrew (1999) [1996]. "Genes in pedigrees: 3.1. Mendelian pedigree patterns". In Kingston, Fran (ed.). Human Molecular Genetics. BIOS Scientific Publishers (2 ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-85996-202-2. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

External links

- White Spotting - This page includes pictures of many of the forms of dominant white.