| Old Swedish | |

|---|---|

| Region | Sweden coastal Finland and Estonia |

| Era | Evolved into Modern Swedish by the 16th century |

| Latin, Runic | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | (covered by non)[1] |

non-swe | |

| Glottolog | None |

| Part of a series on |

| Old Norse |

|---|

|

| WikiProject Norse history and culture |

Old Swedish (Modern Swedish: fornsvenska) is the name for two distinct stages of the Swedish language that were spoken in the Middle Ages: Early Old Swedish (Klassisk fornsvenska), spoken from about 1225 until about 1375, and Late Old Swedish (Yngre fornsvenska), spoken from about 1375 until about 1526.[2]

Old Swedish developed from Old East Norse, the eastern dialect of Old Norse. The earliest forms of the Swedish and Danish languages, spoken between the years 800 and 1100, were dialects of Old East Norse and are referred to as Runic Swedish and Runic Danish because at the time all texts were written in the runic alphabet. The differences were only minute, however, and the dialects truly began to diverge around the 12th century, becoming Old Swedish and Old Danish in the 13th century. It is not known when exactly Elfdalian began to diverge from Swedish.

Early Old Swedish was markedly different from modern Swedish in that it had a more complex case structure and had not yet experienced a reduction of the gender system and thus had three genders. Nouns, adjectives, pronouns and certain numerals were inflected in four cases: nominative, genitive, dative and accusative.

Development

Early Old Swedish

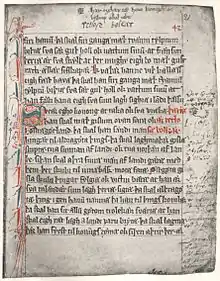

The writing of the Westrogothic law marked the beginning of Early Old Swedish (klassisk fornsvenska or äldre fornsvenska; 1225–1375), which had developed from Old East Norse. It was the first Swedish language document written in the Latin alphabet, and its oldest fragments have been dated to around the year 1225.

Old Swedish was relatively stable during this period. The phonological and grammatical systems inherited from Old Norse were relatively well preserved and did not experience any major changes.

Most of the texts from the Early Old Swedish period were written in Latin, as it was the language of knowledge and the Church. However, Old Swedish was used as a literary language as well, and laws especially were written in it; of the 28 surviving manuscripts from this period, 24 contain law texts.[3] Much of the knowledge of Old Swedish comes from these law texts.[4] In addition to laws, some religious and poetic texts were also written in Old Swedish.

Loanwords

The Catholic Church and its various monastic orders introduced many new Greek and Latin loanwords into Old Swedish. Latin especially had an influence on the written language.[5]

The Middle Low German language also influenced Old Swedish due to the economic and political power of the Hanseatic League during the 13th and 14th centuries. Accordingly, loanwords relating to warfare, trade, crafts and bureaucracy entered the Swedish language directly from Low German, along with some grammatical suffixes and conjunctions. The prefixes be-, ge- and för- that can be found in the beginning of modern Swedish words came from the Low German be-, ge- and vor-. Some words were replaced with new ones: the native word for window, vindøgha, was replaced with fönster, eldhus (kitchen) was replaced with kök and gælda (to pay) with betala.[5] Some of these words still exist in Modern Swedish but are often considered archaic or dialectal; one example is the word vindöga (window). Many words related to seafaring were borrowed from Dutch.

The influence of Low German was so strong that the inflectional system of Old Swedish was largely broken down.[6]

Late Old Swedish

In contrast to the stable Early Old Swedish, Late Old Swedish (yngre fornsvenska; 1375–1526) experienced many changes, including a simplification of the grammatical system and a vowel shift, so that in the 16th century the language resembled modern Swedish more than before. The printing of the New Testament in Swedish in 1526 marked the starting point for modern Swedish.

In this period Old Swedish had taken in a large amount of new vocabulary primarily from Latin, Low German and Dutch. When the country became part of the Kalmar Union in 1397, many Danish scribes brought Danicisms into the written language.

Orthography

Old Swedish used some letters that are no longer found in modern Swedish: ⟨æ⟩ and ⟨ø⟩ were used for modern ⟨ä⟩ and ⟨ö⟩ respectively, and ⟨þ⟩ could stand for both /ð/ (th as in that) and /θ/ (th as in thing). In the latter part of the 14th century ⟨þ⟩ was replaced with ⟨th⟩ and ⟨dh⟩.

The grapheme ⟨i⟩ could stand for both the phonemes /i/ and /j/ (e.g. siæl (soul), själ in modern Swedish). The graphemes ⟨u⟩, ⟨v⟩, and ⟨w⟩ were used interchangeably with the phonemes /w/ ~ /v/ and /u/ (e.g. vtan (without), utan in modern Swedish), and ⟨w⟩ could also sometimes stand for the consonant-vowel combinations /vu/ and /uv/: dwa (duva or dove).

Certain abbreviations were used in writing, such as mꝫ for meþ (modern med, with).[7] The letter combinations ⟨aa⟩, ⟨ae⟩ and ⟨oe⟩ were often written so that one of the letters stood above the other as a smaller letter, ⟨aͣ⟩, ⟨aͤ⟩ and ⟨oͤ⟩, which led to the development of the modern letters ⟨å⟩, ⟨ä⟩, and ⟨ö⟩.

Phonology

The root syllable length in Old Swedish could be short (VC), long (VːC, VCː) or overlong (VːCː).[8] During the Late Old Swedish period the short root syllables (VC) were lengthened and the overlong root syllables (VːCː) were shortened, so modern Swedish only has the combinations VːC and VCː. Unlike in modern Swedish, a short vowel in Old Swedish did not entail a long consonant.

There were eight vowels in Early Old Swedish: /iː, yː, uː, oː, eː, aː, øː, ɛː/. A vowel shift (stora vokaldansen) occurred during the Late Old Swedish period, which had the following effects:

- [uː] became [ʉː] (hūs [huːs] > hus [hʉːs], house)

- [oː] became [uː] (bōk [boːk] > bok [buːk], book)

- [aː] became [oː] (blā [blaː] > blå [bloː], blue)

| Consonants | Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | p(:) b(:) | t(:) d(:) | k(:) g(:) | |||

| Nasal | m(:) | n(:) | ŋ: | |||

| Fricative | f v | θ ð | s(:) | ɣ | h | |

| Approximant | w | l | j | ʟ | ||

| Rhotic | r |

The consonant sounds were largely the same as in modern Swedish, with the notable exceptions of /ð/ and /θ/, which do not exist in modern Swedish (although the former is preserved in Elfdalian and to some extent also the latter). The Modern Swedish tje-sound ([ɕ]) and sje-sound ([ɧ]) were probably [t͡ʃ] and [ʃ], respectively, similar to their values in modern Finland Swedish. A similar change can be seen from Old Spanish [t͡s/d͡z] and [ʃ/ʒ] to Modern Spanish [s/θ] and [x].

The Proto-Germanic phoneme /w/ was preserved in initial sounds in Old Swedish (w-) and did survive in rural Swedish dialects in the provinces of Skåne, Halland, Västergötland and south of Bohuslän into the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. It is still preserved in the Dalecarlian dialects in the province of Dalarna, Sweden. The /w/-phoneme did also occur after consonants (kw-, tw- etc.) in Old Swedish and did so into modern times in said dialects, as well as in the Westro- and North Bothnian tongues in northern Sweden.[9][10]

Grammar

Nominal morphology

In Early Old Swedish

The most defining difference between Old Swedish and modern Swedish was the more complex grammatical system of the former. In Old Swedish nouns, adjectives, pronouns and certain numerals were inflected in four cases (nominative, genitive, dative and accusative), whereas modern standard Swedish has reduced the case system to a common form and a genitive (some dialects retain distinct dative forms). There were also three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine and neuter), still retained in many dialects today, but now reduced to two in the standard language, where the masculine and feminine have merged. These features of Old Swedish are still found in modern Icelandic and Faroese; the noun declensions are almost identical.

Noun declensions fell under two categories: weak and strong.[11] The weak masculine, feminine and neuter nouns had their own declensions and at least three groups of strong masculine nouns, three groups of strong feminine nouns and one group of strong neuter nouns can be identified. Below is an overview of the noun declension system:

The noun declension system[11]

- Vowel stems (strong declension)

- a-stems

- a-stems

- ja-stems

- ia-stems

- ō-stems

- ō-stems

- jō-stems

- iō-stems

- i-stems

- u-stems

- a-stems

- Consonant n-stems (weak declension)

- n-stems

- an-stems

- ōn, ūn-stems

- īn-stems

- n-stems

- Consonant stems

- monosyllabic stems

- r-stems

- nd-stems

Some noun paradigms of the words fisker (fish), sun (son), siang (bed), skip (ship), biti (bit) and vika (week):[12]

| Masculine a-stems | Masculine u-stems | Feminine ō-stems | Neuter a-stems | Masculine an-stems | Feminine ōn-stems | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sg.Nom. | fisker | sun | siang | skip | biti | wika |

| Sg.Acc. | fisk | bita | wiku | |||

| Sg.Gen. | fisks | sunar | siangar | skips | ||

| Sg.Dat. | fiski | syni | siangu | skipi | ||

| Pl.Nom. | fiskar | synir | siangar | skip | bitar | wikur |

| Pl.Acc. | fiska | syni | bita | |||

| Pl.Gen. | suna | sianga | skipa | wikna | ||

| Pl.Dat. | fiskum | sunum | siangum | skipum | bitum | wikum |

In Late Old Swedish

By the year 1500 the number of cases in Old Swedish had been reduced from four (nominative, genitive, dative and accusative) to two (nominative and genitive). The dative case, however, lived on in a few dialects well into the 20th century.

Other major changes include the loss of a separate inflectional system for masculine and feminine nouns, pronouns and adjectives in the course of the 15th century, leaving only two genders in the standard Swedish language, although three genders are still common in many of the dialects. The old dative forms of the personal pronouns became the object forms (honom, henne, dem; him, her, them) and -s became more common as the ending for the genitive singular.

Adjectives

Adjectives and certain numerals were inflected according to the gender and case the noun they modified was in.[13] Below is a table of the inflection of weak adjectives.[14]

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular nominative | -i, -e | -a, -æ | -a, -æ |

| Singular oblique | -a, -æ | -u, -o | |

| Plural | -u, -o | ||

Verbs

Verbs in Old Swedish were conjugated according to person and number. There were four weak verb conjugations and six groups of strong verbs.[11] The difference between weak and strong verbs is in the way the past tense (preterite) is formed: strong verbs form it with a vowel shift in the root of the verb, while weak verbs form it with a dental suffix (þ, d or t).[15]

Strong verbs

The verbs in the table below are bīta (bite), biūþa (offer), wærþa (become), stiæla (steal), mæta (measure) and fara (go).[15]

| Strong verbs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I group | II group | III group | IV group | V group | VI group | |

| Infinitive | bīta | biūþa | wærþa; warþa | st(i)æla | m(i)æta | fara |

| Past participle | bītin | buþin | (w)urþin | stulin; stolin | m(i)ætin | farin |

| Present participle | bītande | biūþande | wærþande | stiælande | mætande | farande |

| Indicative present | ||||||

| iak/jæk, þū, han/hōn/þæt | bīter | biūþer | wærþer | stiæler | mæter | farer |

| vī(r) | bītom | biūþom | wærþom | stiælom | mætom | farom |

| ī(r) | bītin | biūþin | wærþin | stiælin | mætin | farin |

| þē(r)/þā(r)/þē | bīta | biūþa | wærþa | stiæla | mæta | fara |

| Indicative preterite | ||||||

| iak/jæk, han/hōn/þæt | bēt | bøþ | warþ | stal | mat | fōr |

| þū | bētt | bøþt | warþt | stalt | mast | fōrt |

| vī(r) | bitum | buþum | (w)urþom | stālom | mātom | fōrom |

| ī(r) | bitin | buþin | (w)urþin | stālin | mātin | fōrin |

| þē(r)/þā(r)/þē | bitu | buþu | (w)urþo | stālo | māto | fōro |

| Conjunctive present, Imperative | ||||||

| iak/jæk, þū, han/hōn/þæt | bīte | biūþe | wærþe | stiæle | mæte | fare |

| vī(r) | bītom | biūþom | wærþom | stiælom | mætom | farom |

| ī(r), þē(r)/þā(r)/þē | bītin | biūþin | wærþin | stiælin | mætin | farin |

| Conjunctive preterite | ||||||

| iak/jæk, þū, han/hōn/þæt | biti | buþi | (w)urþe | stāle | māte | fōre |

| vī(r) | bitum | buþum | (w)urþom | stālom | mātom | fōrom |

| ī(r), þē(r)/þā(r)/þē | bitin | buþin | (w)urþin | stālin | mātin | fōrin |

Weak verbs

Weak verbs are grouped into four classes:[11]

- First conjugation: verbs ending in -a(r), -ā(r) in the present tense. Most verbs belong to this class.

- Second conjugation: verbs ending in -e(r), -æ(r) in the present tense.

- Third conjugation: verbs ending in -i(r), -ø(r) in the present tense.

- Fourth conjugation: these verbs have a more or less irregular conjugation. About twenty verbs belong to this class.

Inside the conjugation classes the weak verbs are also categorised into further three classes:[11]

- I: those ending in -þe in the preterite

- II: those ending in -de in the preterite

- III: those ending in -te in the preterite

Syntax

Word order was less restricted in Old Swedish than modern Swedish due to complex verbal morphology. Both referential and nonreferential subjects could be left out as verbal structures already conveyed the necessary information, in much the same way as in languages such as Spanish and Latin.

In nominal phrases the genitive attribute could stand both before and after the word it modified, i.e. one could say his house or house his. The same was true for pronouns and adjectives (that house or house that; green pasture or pasture green). During the Late Old Swedish period the usage of the genitive attribute became increasingly more restricted, and it nearly always came to be placed before the word it modified, so in modern Swedish one would usually only say hans hus (his house), or in some dialects or manners of emphasis, huset hans, but almost never hus hans. However, this too has lived on in some dialects, like in Västgötska, where the use of mor din (mother yours) has been common.[lower-alpha 1]

Personal pronouns

Below is a table of the Old Swedish personal pronouns:[11][16]

| Singular | Plural | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | |||||

| masc. | fem. | neut. | masc. | fem. | neut. | |||||

| Nominative | iak, jæk | þu | han | hon | þæt | wi(r) | i(r) | þe(r) | þa(r) | þe, þøn |

| Accusative | mik | þik | hana | os | iþer | þa | ||||

| Dative | mæ(r) | þæ(r) | hanum | hænni | þy | þem | ||||

| Genitive | min | þin | hans | hænna(r) | þæs | war(a) | iþer, iþra | þera | ||

Numerals

The Old Swedish cardinal numbers are as follows.[11] Numbers from one to four decline in the nominative, genitive, dative and accusative cases and in all three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter); here the nominative forms are given. Numbers above four are indeclinable.[11]

| Old Swedish | Modern Swedish | Old Swedish | Modern Swedish | ||

| 1 | ēn, ēn, ēt | en, (dialectal f. e, ena), ett | 11 | ællivu | elva |

| 2 | twē(r), twār, tū | två, tu | 12 | tolf | tolv |

| 3 | þrī(r), þrēa(r), þrȳ | tre | 13 | þrættān | tretton |

| 4 | fiūri(r), fiūra(r), fiughur | fyra | 14 | fiughurtān | fjorton |

| 5 | fǣm | fem | 15 | fǣm(p)tan | femton |

| 6 | sæx | sex | 16 | sæxtān | sexton |

| 7 | siū | sju | 17 | siūtān | sjutton |

| 8 | ātta | åtta | 18 | atertān | arton (archaic aderton) |

| 9 | nīo | nio | 19 | nītān | nitton |

| 10 | tīo | tio | 20 | tiughu | tjugo |

The higher numbers are as follows. The numbers 21–29, 31–39, and so on are formed in the following way: ēn (twēr, þrīr, etc.) ok tiughu, ēn ok þrǣtighi, etc.[11]

| Old Swedish | Modern Swedish | Old Swedish | Modern Swedish | ||

| 30 | þrǣtighi | trettio | 70 | siūtighi | sjuttio |

| 31 | ēn ok þrǣtighi | trettioett | 80 | āttatighi | åttio |

| 40 | fiūratighi | fyrtio | 90 | nīotighi | nittio |

| 50 | fǣmtighi | femtio | 100 | hundraþ | hundra |

| 60 | s(i)æxtighi | sextio | 1000 | þūsand | tusen |

Examples

Västgötalagen

This is an extract from the Westrogothic law (Västgötalagen), which is the oldest continuous text written in the Swedish language, and was compiled during the early 13th century. The text marks the beginning of Old Swedish.

- Dræpær maþar svænskan man eller smalenskæn, innan konongsrikis man, eigh væstgøskan, bøte firi atta ørtogher ok þrettan markær ok ænga ætar bot. [...] Dræpar maþær danskan man allæ noræn man, bøte niv markum. Dræpær maþær vtlænskan man, eigh ma frid flyia or landi sinu oc j æth hans. Dræpær maþær vtlænskæn prest, bøte sva mykit firi sum hærlænskan man. Præstær skal i bondalaghum væræ. Varþær suþærman dræpin ællær ænskær maþær, ta skal bøta firi marchum fiurum þem sakinæ søkir, ok tvar marchar konongi.

Modern Swedish:

- Dräper man en svensk eller en smålänning, en man ifrån konungariket, men ej en västgöte, så bötar man tretton marker och åtta örtugar, men ingen mansbot. [...] Dräper man en dansk eller en norrman bötar man nio marker. Dräper man en utländsk man, skall man inte bannlysas utan förvisas till sin ätt. Dräper man en utländsk präst bötar man lika mycket som för en landsman. En präst räknas som en fri man. Om en sörlänning dräps eller en engelsman, skall han böta fyra marker till målsäganden och två marker till konungen.

English:

- If someone slays a Swede or a Smålander, a man from the kingdom, but not a West Geat, he will pay eight örtugar and thirteen marks, but no wergild. [...] If someone slays a Dane or a Norwegian, he will pay nine marks. If someone slays a foreigner, he shall not be banished and have to flee to his clan. If someone slays a foreign priest, he will pay as much as for a fellow countryman. A priest counts as a free man. If a Southerner is slain or an Englishman, he shall pay four marks to the plaintiff and two marks to the king.

The Life of Saint Eric

This text about Eric IX (ca. 1120–1160) can be found in the Codex Bureanus, a collection of Old Swedish manuscripts from the mid-14th century.[17]

- Hǣr viliom wī medh Gudz nādhom sighia medh faam ordhom aff thø̄m hælgha Gudz martire Sancto Ĕrīco, som fordum war konungher ī Swērīke. Bādhe aff ǣt ok ædle han war swā fast aff konunga slækt som aff androm Swērīkis høfdingiom. Sidhan rīkit var v̄tan forman, ok han var kiǣr allom lanzins høfdingiom ok allom almōganom, thā valdo thē han til konungh medh allom almōghans gōdhwilia, ok sattis hedherlīca ā konungx stool vidh Upsala.

Translation:

- Here we want to say with God's grace a few words about that holy God's martyr Saint Eric, who was earlier the King of Sweden. In both heritage and nobility he was fastly of royal extraction as other Swedish leaders. Since the realm was without a leader and he was beloved by all of the land's nobility and all of the common people, the commoners chose him as King with all of their good will, and sat him reverentially on the King's throne at Uppsala.

See also

Notes

- ↑ In Västgötska, molin can also be used instead of mor din. Västgötska words and expressions (Swedish)

Bibliography

- Bergman, Gösta.Kortfattad svensk språkhistoria. Prisma 1980.

- Kirro, Arto; Himanen, Ritva. Textkurs i fornsvenska. Universitetet 1988.

- Noreen, Adolf. Altschwedische Grammatik. 1904.

- Wessén, Elias. Fornsvenska texter: med förklaringar och ordlista. Läromedelsförlagen, Svenska bokförlagen 1969.

References

- ↑ CR Comments 2009-09 Archived 6 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine. SIL International.

- ↑ Fortescue, Michael D. Historical linguistics 2003: selected papers from the 16th International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Copenhagen, 11–15 August 2003. John Benjamins Publishing Company 2005. p. 258. Accessed through Google Books.

- ↑ Bandle, Oskar; Elmevik, Lennart; Widmark, Gun. The Nordic languages: An International Handbook of the History of the North Germanic Languages. Volume 1. Walter de Gruyter 2002. Accessed through Google Books.

- ↑ Klassisk- och yngre fornsvenska. Svenska språkhistoria. Retrieved 2009-28-10.

- 1 2 Grünbaun, Katharina. Svenska språket Archived 25 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Svenska institutet.

- ↑ Hird, Gladys; Huss, Göran; Hartman, Göran. Swedish: an elementary grammar reader. Cambridge University Press 1980. p. 1. Accessed through Google Books.

- ↑ Beukema, Frits H.; van der Wurff, Wim. Imperative clauses in generative grammar: studies in honour of Frits Beukema. John Benjamins Publishing Company 2007. p. 195, note 14. Accessed through Google Books.

- ↑ Dahl, Östen; Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Maria. The Circum-Baltic languages: typology and contact. John Benjamins Publishing Company 2001. Accessed through Google Books.

- ↑ Otto v. Friesen: Om w-ljud och v-ljud i fornvästnordiskan. I Arkiv för Nordisk Filologi. 1927. p. 128

- ↑ Elias Wessén, Svensk språkhistoria I: Ljudlära och ordböjningslära. Fjärde upplagan. Stockholm 1955. p. 27

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Noreen, Adolf: Altschwedische Grammatik, mit Einschluss des Altgutnischen Archived 19 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. 1904. Retrieved 2009-28-10.

- ↑ Faarlund, Jan Terje. Grammatical relations in change. John Benjamins Publishing Company 2001. p. 249. Accessed through Google Books.

- ↑ Pettersson, Gertrud. Svenska språket under sjuhundra år. Lund 2005.

- ↑ Wischer, Hilse; Diewald, Gabriele. New reflections on grammaticalization. John Benjamins Publishing Company 2002. p. 52. Accessed through Google Books.

- 1 2 Germanic languages: conjugate Old Swedish verbs Archived 21 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Verbix.com. Retrieved 2009-28-10.

- ↑ Roelcke, Thorsten. Variationstypologie: ein sprachtypologisches Handbuch der europäischen Sprachen in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Walter de Gruyter 2003. p. 195. Accessed through Google Books.

- ↑ Gordon and Taylor Old Norse readings Archived 22 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Germanic Lexicon Project. Section "XX The Life of Saint Eric". Retrieved 2009-28-10.

External links

- Altschwedische Grammatik by Adolf Noreen at the Germanic Lexicon Project

- Old Swedish verb conjugator