| Eastern Hills | |

|---|---|

View of the Eastern Hills, from Salitre | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,600–3,550 m (8,530–11,650 ft) |

| Prominence | 950 m (3,120 ft) |

| Listing | Guadalupe Hill – 3,317 m (10,883 ft) Monserrate – 3,152 m (10,341 ft) Aguanoso, Pico del Águila, El Cable, El Chicó, El Chiscal, La Laguna, Pan de Azúcar, La Teta |

| Coordinates | 4°36′21″N 74°02′23″W / 4.60583°N 74.03972°W |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 52 km (32 mi) |

| Width | 0.4–8 km (0.25–4.97 mi) |

| Area | 136.3 km2 (52.6 sq mi) |

| Naming | |

| Native name | Cerros Orientales de Bogotá (Spanish) |

| Geography | |

Eastern Hills | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Settlements | Bogotá D.C., Usaquén, Chapinero, El Chicó, Rosales, Chapinero Alto, Santa Fe, Laches, La Perseverancia, San Cristóbal, Veinte de Julio, Usme, Chía, La Calera, Choachí, Ubaque and Chipaque |

| Parent range | Altiplano Cundiboyacense Eastern Ranges, Andes |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Andean |

| Age of rock | Cretaceous-Holocene |

| Mountain type | Fold and thrust belt |

| Type of rock | Sandstones, shales and conglomerates |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | Pre-Columbian era |

| Access | Roads: Bogotá – La Calera road Avenida Circunvalar Autopista Bogotá – Villavicencio Main trails: Pilgrimage trail to Monserrate Las Delicias Trail Las Moyas Trail La Vieja Trail Cable car Candelaria–Monserrate |

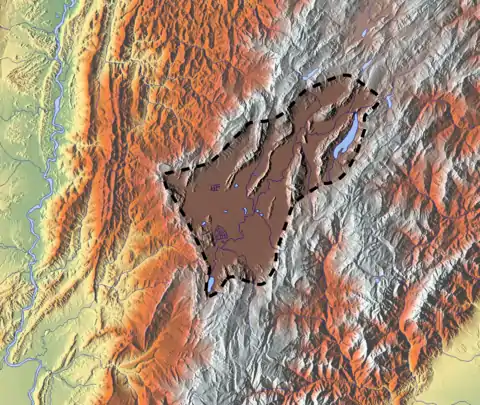

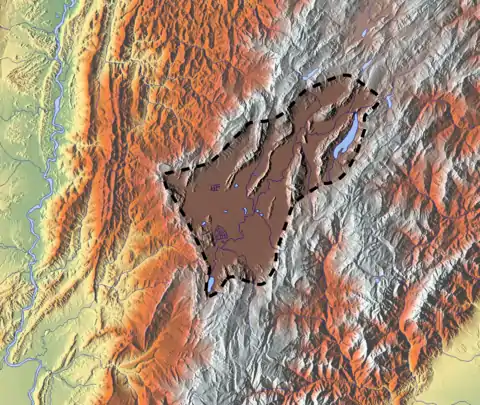

The Eastern Hills (Spanish: Cerros Orientales) are a chain of hills forming the eastern natural boundary of the Colombian capital Bogotá. They are part of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, the high plateau of the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes. The Eastern Hills are bordered by the Chingaza National Natural Park to the east, the Bogotá savanna to the west and north, and the Sumapaz Páramo to the south. The north-northeast to south-southwest trending mountain chain is 52 kilometres (32 mi) long and its width varies from 0.4 to 8 kilometres (0.25 to 4.97 mi). The highest hilltops rise to 3,600 metres (11,800 ft) over the western flatlands at 2,600 metres (8,500 ft). The Torca River at the border with Chía in the north, the boquerón (wide opening) Chipaque to the south and the valley of the Teusacá River to the east are the hydrographic limits of the Eastern Hills.

Geologically, the Eastern Hills are the result of the westward compression along the Bogotá Fault, that thrusted the lower Upper Cretaceous rocks of the Chipaque Formation and Guadalupe Group onto the latest Cretaceous to Eocene sequence of the Guaduas, Bogotá, Cacho and Regadera Formations. The fold and thrust belt of the Eastern Hills was produced by the Andean orogeny with the main phase of tectonic compression and uplift taking place in the Pliocene. During the Pleistocene, the Eastern Hills were covered by glaciers feeding a large paleolake (Lake Humboldt) that existed on the Bogotá savanna and is represented today by the many wetlands of Bogotá.

The main tourist attractions of the Eastern Hills of Bogotá are the Monserrate and Guadalupe Hills, the former a pilgrimage site for centuries. Other trails in the Eastern Hills follow the creeks of La Vieja, Las Delicias and others. The busy road Bogotá – La Calera crosses the Eastern Hills in the central-northern part and the highway between Bogotá and Villavicencio traverses the southernmost area of the hills. The eastern side of the Eastern Hills is part of the municipalities La Calera, Choachí, Ubaque and Chipaque.

The Eastern Hills were sparsely populated in pre-Columbian times, considered sacred by the indigenous Muisca. The native people constructed temples and shrines in the Eastern Hills and buried their dead there. The Guadalupe and Monserrate Hills, important in Muisca religion and archaeoastronomy, are the hilltops from where Sué, the Sun, rises on the December and June solstices respectively, when viewed from the present-day Bolívar Square. The construction and expansion of the Colombian capital in Spanish colonial times caused excessive deforestation of the Eastern Hills. Reforestations were executed in the 1930s and 1940s.

Large parts of the Eastern Hills are designated as a natural reserve with a variety of flora and fauna, endemic to the hills. Despite its status as a protected area, the Eastern Hills lie in an urban setting with more than ten million inhabitants and are affected by mining activities, illicit construction, stream contamination, and frequent forest fires. Several proposals to fight the environmental problems have been written in the past decades.

Description

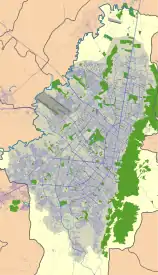

The Eastern Hills cover an area of approximately 13,630 hectares (33,700 acres), are oriented north-northeast to south-southwest along a length of 52 kilometres (32 mi), have a width between 0.4 and 8 kilometres (0.25 and 4.97 mi) and range in elevation from 2,600 to 3,550 metres (8,530 to 11,650 ft).[1] They border the Colombian capital Bogotá to the east. The main hills are Cerro Guadalupe at 3,317 metres (10,883 ft) and Monserrate at 3,152 metres (10,341 ft).[2][3][4] Other hills are Aguanoso, Pico del Águila, El Cable, El Chicó, El Chiscal, La Laguna, Pan de Azúcar and La Teta. From north to south, the rural areas of the localities of Usaquén, Chapinero, Santa Fe, San Cristóbal and Usme are part of the Eastern Hills.[5] Of the area of Santa Fe, 84.5% is rural area, located in the Eastern Hills.[6] The municipalities Chía, La Calera, Choachí, Ubaque and Chipaque are partly in the Eastern Hills. The Cerros Orientales are an important water source for the Colombian capital.[2] The San Rafael Reservoir, administered by the municipality La Calera, is east of the Eastern Hills.

Etymology

Bogotá, and as a result the Eastern Hills of Bogotá, are named after the original main settlement of the Muisca; Bacatá. Bacatá in Muysccubun means "(enclosure) outside of the farmfields" or "limit of the farmfields",[7] referring to the seat of the zipa in present-day Funza on the right bank of the Bogotá River. Bacatá is a combination of bac or uac,[8] ca,[9] and tá,[10] meaning "outside", "enclosure" and "farmfield(s)" respectively.

Alternative spellings are Muequetá, or Muyquytá,[11] and the word is transliterated in Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada as Bogothá.[12]

Geography

|

|

|

| ||

| ||

| ||

| The Eastern Hills of Bogotá border the municipalities La Calera, Choachí, Ubaque and Chipaque. | ||

Geographically, the Eastern Hills form part of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, the high plateau in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes. The natural boundaries of the Eastern Hills are the Bogotá savanna in the north and west, the hills of Chingaza National Natural Park in the east and the mountains of Sumapaz Páramo in the south. The northern hydrographic limit is the Torca River at the border with Chía, the southern limit the boquerón Chipaque and the eastern hydrographic boundary is formed by the Teusacá River.[2]

Geology

.jpg.webp)

The rocks forming the Eastern Hills range in age from Late Cretaceous to Paleogene and are covered by sub-recent sediments of the Pleistocene and Holocene. The contact between the Maastrichtian to Lower Paleocene Guaduas and Late Paleocene Cacho Formations is discordant, indicating the first uplift of the Andes. Between the Eocene and Pleistocene a hiatus is present, where the Pleistocene formations are followed by Holocene unconsolidated sediments.[2][13]

The Cenomanian–Turonian Chipaque Formation got its name from the village Chipaque and is the oldest stratigraphical unit outcropping in the eastern flank of the Eastern Hills. It comprises laminated organic to highly organic shales and mudstones with intercalated sandstone beds. The overlying Guadalupe Group, of Campanian to Maastrichtian age, consists of four formations, from base to top: Arenisca Dura, Plaeners, Arenisca de Labor, and Arenisca Tierna. Some authors define the Guadalupe Group as a formation and call the individual formations, members.[14] The thickness of the Guadalupe Group in its type localities Guadalupe and El Cable Hills is 750 metres (2,460 ft).[15] The competent hilltops of the Eastern Hills are represented by the resistant members of the Guadalupe Group; in the northern parts of the Cerros Orientales they comprise the Labor and Tierna members and are in the southern area represented by the Arenisca Dura.[13]

Concordantly overlying the Guadalupe Group is the Maastrichtian to Early Paleocene Guaduas Formation, composed of well-laminated compacted grey shales and calcitic claystones with sandstone banks and in the lower parts of the stratigraphical sequence numerous coal beds. In the synclinal of the Bogotá savanna, the thickness of Guaduas varies between 250 and 1,200 metres (820 and 3,940 ft). The Late Paleocene Cacho Formation, a relatively thin 50-to-400-metre (160 to 1,310 ft) stratigraphical unit following the Guaduas Formation, white, yellow and reddish in colour, is represented by thick sandstone banks with intercalations of thin shale beds.[15]

The Bogotá Formation, named after the capital, is a Paleocene to Lower Eocene argillaceous unit, concordantly overlying the lower Paleogene sequence. The formation is composed of grey, purple and red shales with micaceous sandstone beds towards the top of the stratigraphical unit. The thickness in the subsurface of the Bogotá savanna ranges from 800 to 2,000 metres (2,600 to 6,600 ft) and outcrops at the edges of the flatlands.[13][15] In this formation fossils of the ungulate Etayoa bacatensis, named after the name for the savanna and its main settlement in present-day Funza, used by the native Muisca; Bacatá, have been found.[16][17] The estimated size of the South American hoofed mammal was that of a dog.[18] Other fossilised fragments found in the Bogotá Formation are molds of Stephania palaeosudamericana and Menispina evidens.[19][20][21]

Discordantly overlying the Lower Eocene is the Middle Eocene Regadera Formation, consisting of quartzitic and feldspar-rich thick medium- to coarse-grained to conglomeratic sandstone beds intercalated with thin pink claystones. The total thickness of the Regadera unit is very variable throughout the area.[15] Following the Regadera Formation is the discordant Late Eocene Usme Formation, named after the locality in southeastern Bogotá, for the most part located in the Eastern Hills. The unit with a total thickness of 125 metres (410 ft) consists of a lower member composed of grey shales with occasional fine-grained sandstone layers and an upper member of coarse-grained quartzarenites and conglomerates. The Usme Formation represents the last Paleogene stratigraphic unit before the hiatus of approximately 30–35 million years.[22]

While the Bogotá savanna contains two other formations; the Pliocene Tilatá and Plio-Pleistocene Sabana formations, the Eastern Hills lack these late Neogene stratigraphical units.[13] The basal unit of the Quaternary sequence is the fluvio-lacustrine Subachoque Formation, present in the subsurface of the foreland area of the Eastern Hills. The Tunjuelo Formation, named after the Tunjuelo River that is fed by the Eastern Hills creeks in the south and the Sumapaz Mountains to the southeast, is the last consolidated stratigraphical unit. Coarse-grained Quaternary fluvio-glacial deposits as a result of the Eastern Hills run-off through the San Cristóbal, San Francisco and Arzobispo rivers and the many creeks, intercalate with clays and conglomerates.[22] The Tunjuelo Formation has a maximum thickness of 150 metres (490 ft).[23] This Pleistocene sequence is followed by poorly consolidated to unconsolidated sediments of lacustrine origin, Pleistocene–Holocene in age, mixed with the erosional products of the Eastern and Suba Hills and Sumapaz mountains that form the alluvium.[24]

| Code | Formation | Age | Lithologies | Type locality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qdp | Alluvium | Pleistocene to Holocene | Sands, shales and conglomerates | |

| Qcc | Tunjuelo | Pleistocene | Conglomerates with sandstones and lime | Tunjuelo Valley |

| Qsu | Subachoque | Early Pleistocene | Fluvio-lacustrine shales with sand and gravel intercalations | Subachoque Synclinal |

| Hiatus | ||||

| Tsu | Usme | Late Eocene | Shales and siltstones | Usme Synclinal |

| Tpr | Regadera | Middle Eocene | Cross-laminated sandstones and conglomerates | Regadera Valley |

| Tpb | Bogotá | Late Paleocene to Early Eocene | Mudstones and shales with intercalated sandstones and coal | Ciudad Bolívar |

| Tpc | Cacho | Paleocene | Coarse-grained sandstones and conglomerates | Soacha |

| Ktg | Guaduas | Maastrichtian to Early Paleocene | Intercalated sandstones and shales, coalbeds | Guaduas |

| Ksg | Guadalupe | Campanian to Maastrichtian | Grey sandstones and shales | Guadalupe Hill |

| Ksch | Chipaque | Cenomanian–Turonian | Organic shales with sandstone banks | Chipaque |

Soils

The characterisation of soils is mainly related to the inclination of the terrain. The Asociación Monserrate type soil occurs in areas with inclinations between 30 and 75%. The dark well-draining soils originate from the Plaeners Formation of the Guadalupe Group with influence of volcanic ashes, are thinner than 50 centimetres (20 in) and very acidic with a pH of 4.4.[25] The Asociación Cabrera-Cruz Verde type soils exist at moderate inclinations between 12 and 50%, are derived from argillaceous rocks with volcanic ash influence, have a fast drainage and a pH between 4.5 and 5.0.[26] The Complejos Coluviales are present in the undulated areas with inclinations below 12%, susceptible to erosion, and are apt for intensive agriculture.[26]

Faults

The main fault in the Eastern Hills is the longitudinal eastward dipping thrust fault called the Bogotá Fault, striking north-northwest to south-southeast, parallel to the longitudinal axis of the Eastern Hills. It forms the tectonic limit with the Bogotá savanna and acts as a barrier for aquifers.[27] The compressional tectonics thrusted the Cretaceous units of Guadalupe and Chipaque on top of the younger Guaduas, Cacho and Bogotá Formations.[13] The transversal faults oriented northeast–southwest to the Bogotá Fault are from north to south the Usaquén, Río Juan Amarillo, San Cristóbal and Soacha Faults.[28] The compressional La Cajita Fault is parallel to the main strike of the Bogotá Fault and the Eastern Hills and outcrops in the Sumapaz Mountains to the south.[29]

Tectonic evolution

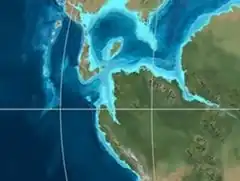

| Paleogeography of Colombia | |

|

120 Ma |

|

105 Ma |

|

90 Ma |

|

65 Ma |

|

50 Ma |

|

35 Ma |

|

20 Ma |

|

Present |

The tectonic evolution of the area of the present-day Eastern Hills started with a marine back-arc basin in the Late Jurassic.[30] The Early Cretaceous stages Berriasian and Valanginian were dominated by the presence of a marine incursion from the proto-Caribbean into the continent of South America, in those times still attached to Africa and Antarctica. The central region of current Colombia, the later Eastern Cordillera, was characterised by the deposition of calcareous shales with turbidite deposits from the Cáqueza area. During the Late Aptian to Early Albian, a marine shale-dominated sedimentation existed with more carbonate-rich deposits to the north, represented by the mosasaur fossil-bearing Paja Formation in Boyacá. The Turonian stage of the Cretaceous era experienced a worldwide anoxic event that produced highly organic shales in the area, today represented by the Chipaque Formation. The Upper Cretaceous sequence, illustrated in the stratigraphy by the Guadalupe Group, was deposited in a marine environment with alternating sandstones and shales.[31]

The Late Cretaceous to Paleocene was characterised by a foreland basin setting; the Western and Central Ranges of the Colombian Andes already started forming, while the eastern Andes were still in a phase of marine to littoral sedimentation. During the Early Paleocene, the Peñon-Cobardes and Arcabuco anticlines started to rise, when the southern parts of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense were still submerged and characterised by a fluvio-deltaic depositional environment.[32]

The Late Paleocene marked a time where continued uplift of the two westernmost ranges were exhumed and provided sediments for the narrow basin in the area of the Eastern Hills. The Bogotá Formation reflects a shallow marine environment with occasional turbiditic flows.[33] The Early Eocene is characterised by ongoing uplift to the west of the Bogotá area and emergence of the Upper Magdalena Valley.[34] During the Late Eocene, the Eastern Hills were exhumed for the first time, providing minor sediment sources for the Bogotá savanna.[35]

During the Early Oligocene, the region of the Eastern Hills and the Bogotá savanna was exhumed, while sedimentation in the Llanos Orientales continued, depositing the Carbonera Formation in a lacustrine-marine setting.[36] By the Late Oligocene, the Eastern Ranges were in a continental environment and deposition shifted towards the Llanos.[37] The northern part of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense experienced exhumation around 26 Ma, while the southern part was exhumed approximately 21 million years ago.[38] In Early to Middle Miocene times, the Eastern and Western Cordilleras enclosed a fluvial depositional environment in the Magdalena Basin.[39] During this epoch in the tectonic history, maximum foreland sedimentation to the east (Medina area) was reached,[40] and a rich fossil fauna was present to the southeast of the Eastern Hills area, in the present-day Tatacoa Desert of Huila. The Konservat-Lagerstätte of the Honda Group at La Venta is one of the most important Neogene paleontological sites of South America, especially in the diversity of mammals found. The fossil community from La Venta, Colombia, demonstrates a degree of phylogenetic richness (i.e., number of taxa) comparable with modern communities.[41] The Late Miocene marked the formation of the continuous chain of the Eastern Andes, leading to erosion of earlier deposited sediments.[42] Based on zircon and apatite fission track data, the uplift between the Early Miocene to Pliocene was slow, subsequently followed by a period of increased tectonic uplift in the last phases of the Andean orogeny.[43]

The Neogene experienced periods of volcanic activity. While the northern areas of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense were affected by the near-surface volcanism of Paipa and Iza, both in Boyacá, the volcanic area closer to the Eastern Hills was located around present-day Guatavita. The volcanism here has been analysed to have been post-Andean uplift.[44] The Plio–Pleistocene period was marked by the presence of a fluvio-lacustrine depositional environment (Lake Humboldt) on the Bogotá savanna, sourced by rivers running off the Eastern Hills. The sedimentological record revealed various stages of infill, where the smaller-scale setting was determined by the paleo-water level and climate conditions. During the coldest periods, Lake Humboldt was surrounded by páramo ecosystems, with plant growth around the lake reducing lake shore erosion.[45] The Latest Pleistocene was characterised by a period of cooling with a minor glacier present in the highest part of the central Eastern Hills.

Moraines in this area have been dated to 18,000 until 15,500 years BP, in the late Last Glacial Maximum.[46]

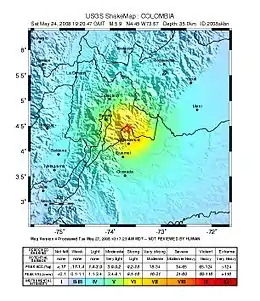

Seismic activity

El Calvario 2008

In the Eastern Hills, a number of historical earthquakes in the seismically active country of Colombia have caused damage. Movement along the Servitá Fault in the eastern flank of the Eastern Ranges, has had the most effect on the surface stability of Bogotá and its hills.[47] The Bogotá Fault has not shown activity and is listed as uncertain.[48] The 1967 Neiva earthquake that occurred on February 9 damaged historical buildings in the foothills of the Eastern Hills. This had happened before with the 1785 Viceroyalty of New Granada earthquake (MS 6.5–7.0; destroying various buildings in Bogotá, as well as the Hermitage on Guadalupe Hill), the 1827 Bogotá earthquake (MS 7.7) and the 1917 Sumapaz earthquake (MS 7.3).[49] The 1966 El Calvario earthquake caused damage in Usme. An earthquake with the epicentre also in El Calvario, Meta, in 2008 caused minor damage in the historic centre of Bogotá.[50]

| Year | Date | Name | Epicentre | Coordinates | Intensity Magnitude |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1644 | March 16 | 1644 Bogotá earthquake | Bogotá | - | - | |

1743 | October 18 | 1743 El Calvario earthquake | El Calvario | VII | ||

1785 | July 12 | 1785 Bogotá earthquake | La Calera | VIII 6.5–7.0 | ||

1826 | June 17 | 1826 Sopó earthquake | Sopó | - | VII | |

1827 | November 16 | 1827 Bogotá earthquake | Popayán | VIII 7.0 | ||

1917 | August 31 | 1917 Sumapaz earthquake | Acacias or Sumapaz | VIII 6.9–7.3 | ||

1928 | November 1 | 1928 Tenza Valley earthquake | Tenza Valley | - | VII | |

1966 | September 4 | 1966 El Calvario earthquake | El Calvario | 5.0 | ||

1967 | February 9 | 1967 Neiva earthquake | Neiva | VI-VII 6.2 | ||

1988 | March 19 | 1988 El Calvario earthquake | El Calvario | 4.8 | ||

2008 | May 24 | 2008 El Calvario earthquake | El Calvario | 5.6 |

Climate

| La Calera – 2,726 metres (8,944 ft)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The climate (Köppen: Cfb) of the Eastern Hills is controlled by the Intertropical Convergence Zone with winds prevailing from the Amazon Region in the east.[59] The climate varies slightly from north to south. The northern parts are characterized by a bimodal precipitation pattern; higher rainfall occurs in the months April–May and November–December, and the northern part of the Eastern Hills is the zone with relatively the most stable temperatures.[60] The southern, topographically higher portion has a monomodal precipitation pattern. Average temperatures depend on the elevation; the zones at 3,100 metres (10,200 ft) have an average annual temperature of 8.4 °C (47.1 °F) and yearly rainfall of 750 millimetres (30 in),[60] while the lower altitudes at 2,750 metres (9,020 ft) have temperatures averaging 13 °C (55 °F).[2] La Calera at 2,726 metres (8,944 ft) has a total annual precipitation of 918 millimetres (36.1 in).[61]

The region of the Páramo del Verjón in the eastern part has temperatures between 6 and 10 °C (43 and 50 °F) and an annual precipitation of 1,100 to 1,500 millimetres (43 to 59 in).[60] The relative humidity is with 78% almost constant across the year, although July is the most humid month with 87%,[2] and January and February register a value of 73%.[60] The total evaporation per year in the upper course of the Teusacá River is 870 millimetres (34 in), while the peaks at 3,100 metres (10,200 ft) have an annual evaporation of 755 millimetres (29.7 in).[60]

Prevalent wind direction is from the southeast, with strongest winds registered in July at 2.0 metres per second (6.6 ft/s) and the lowest values noted in November at 1.5 metres per second (4.9 ft/s).[62] The hours of sunshine vary from 85.9 hours in April to 130.2 hours in December.[2]

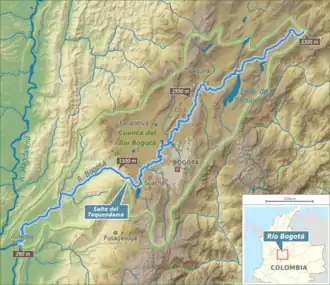

Hydrology

The hydrology of the Eastern Hills is part of the Bogotá River Basin. The main river to the east of the Eastern Hills is the Teusacá River.[63] Various rivers and creeks flowing into the Bogotá savanna are sourced from the Eastern Hills. The most important rivers from south to north are:[63][64][65]

| Zone | Basin | River or creek | Source | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | Fucha | San Cristóbal River | Páramo de Cruz Verde |  |

| Manzanares | Guadalupe Hill | |||

| San Francisco River | Páramo de Cruz Verde | |||

| Central | Arzobispo River | Alto del Cable | ||

| Juan Amarillo or Salitre |

Las Delicias, La Vieja, El Chicó, Los Molinos | Chapinero | ||

| North | Santa Bárbara, Delicias del Carmen, El Cóndor, La Cita, La Floresta |

Northern Eastern Hills | ||

| Torca | El Cedro, San Cristóbal | |||

All rivers and creeks sourced by the Eastern Hills flow into the Bogotá River | ||||

Flora and fauna

The Eastern Hills contain several biomes that differ mainly by elevation. The highest elevated areas are characterised by a páramo ecosystem; from north to south Páramo El Verjón (Parque Ecológico Matarredonda), Páramo de Cruz Verde and Páramo de Chipaque.[66][67] Parque Entrenubes ("Park between the clouds") is just east of the Eastern Hills and is the northernmost part of the Sumapaz Páramo.[68]

Flora

A study of the vegetation cover has revealed the presence of 29 types of vegetation covering 63% of the total area. The remaining 37% is used by urban settlement, agricultural lands and quarries. In the Eastern Hills a total of 443 species of flora have been identified. Of the vascular plants, 156 species in 111 genera and 64 families have been noted.[2]

Fauna

Before the human settlement of the Bogotá savanna, many species of fauna populated the forested remains of the flat lands bordering the Eastern Hills.[69] In the Eastern Hills two species of butterflies have been identified, the Julia butterfly and the common green-eyed white.[70]

Birds

Colombia has the most recorded bird species (1912 as of 2014) in the world.[71] The country accounts for approximately 20% of all the world's discovered species and 60% of those registered in South America.[1] The biodiversity of bird species in the Eastern Hills is higher than in the parks of urban Bogotá and the dense forests and larger space between the urban zones offer superb habitat for 30 families, 92 genera and 119 species.[2] A 2011 study provided data on 67 species in an area of 75 hectares (190 acres).[72] The observation stations were between 2,674 and 3,065 metres (8,773 and 10,056 ft) in elevation.[73]

Mammals

Mammals of 14 families, 17 genera and 18 species have been identified in the Eastern Hills.[2][74] The white-tailed deer served as the staple of the pre-Columbian hunter-gatherers' diet and later as the primary meat of the Muisca cuisine.[75] Until the first half of the twentieth century, such larger species as the puma, spectacled bear and white-tailed deer populated the Eastern Hills, but these have been hunted to extinction locally.[76] In March 2017, a spectacled bear, approximately 11 years old, was killed by unknown people near Chingaza National Park, just east of the Eastern Hills.[77]

Reptiles and amphibians

.jpg.webp)

Reptiles of four families, five genera and five species have been identified in the Eastern Hills.[2][74] Of these species, only the lizards Anadia bogotensis and Proctoporus striatus have been found on the Guadalupe Hill.[78] The striped lightbulb lizard is also present on the terrain of the Universidad de los Andes.[79] Amphibians of four families, six genera and nine species have been identified in the Eastern Hills.[2][74][76]

Fish

Three species of fish have been identified in the waters of the Eastern Hills.[74][76] Of Trichomycterus venulosus only two specimens have been found, and it is thought the species is extinct in the rivers of the Eastern Hills, which may have to do with the introduction of trout.[80]

History

The human history of the Eastern Hills goes back to the latest Pleistocene, when the first humans settled in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes. During the first millennia of the Holocene, the inhabitants of the area survived as hunter-gatherers living in caves and rock shelters. Food was gathered from the surrounding areas, including the Eastern Hills. A sedentary lifestyle was getting more common in this archaic stage and agriculture on the fertile lands of the Bogotá savanna took off around 5000 years BP. Ceramics was introduced to the people of the area around the same time, in their mythology knowledge spread by Bochica.[81]

Archaeological excavations on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense have revealed the oldest dated solar site of the Americas, called by the Spanish El Infiernito (The Little Hell), but known as the Muisca solar observatory of the Leyva Valley. The location in a valley between the surrounding mountains evidenced a concept of archaeoastronomical knowledge of the people of the region; at the summer solstice of June 21 seen from the Muisca solar observatory, the Sun rises exactly from Lake Iguaque, where in the religion of the pre-Hispanic inhabitants the mother and Earth goddess Bachué was born.[82]

A similar site in the Muisca astronomy is Bolívar Square, in the heart of the Colombian capital. At this site, the Spanish conquistadors built the precursor church to the Catedral Basílica Metropolitana de la Inmaculada Concepción. This cathedral was constructed by the early Colombian government in the early 19th century. From the northeastern end of the square, at the winter solstice of December, the Sun rises exactly above Guadalupe Hill (Muysccubun: quijicha guexica; "grandfather's foot") of the Eastern Hills, while at the summer solstice of June Sué appears from Monserrate (Muysccubun: quijicha caca; "grandmother's foot").[83] At the equinoxes of September and March, the Sun rises exactly in the valley between the two summits.[84]

Evidence for use of the Eastern Hills by the Muisca has been found during the 20th and 21st centuries. While the Muisca inhabited mostly the valleys and plains, most notably the Bogotá savanna, they constructed temples and other sacred buildings in the surrounding hills.[85] The present-day municipalities Choachí, Ubaque and Chipaque at the eastern slopes of the Eastern Hills were inhabited by the Muisca. In Choachí, during the first half of the twentieth century an artefact was found, called the Choachí Stone, which is interpreted as a possible relict of the complex lunisolar Muisca calendar, although other interpretations suggest it was a mold for the elaboration of tunjos.[86][87]

The first Europeans who saw and visited the Eastern Hills were the troops led by conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada who entered the Bogotá savanna in March 1537 during what for the Spanish proved to be the deadliest of their conquests of advanced pre-Columbian civilisations. More than 80 percent of his soldiers did not survive the journey from Santa Marta at the Caribbean coast. At the foot of the Eastern Hills, in the present-day La Candelaria, he founded the city of Bogotá on August 6, 1538. Seven months later, Jiménez de Quesada left for Spain with conquistadors Nikolaus Federmann and Sebastián de Belalcázar who had reached the new capital of the New Kingdom of Granada in early 1539. Federmann had crossed the Eastern Ranges from the Llanos Orientales to enter the Bogotá savanna across the Sumapaz Páramo, to the southwest of the Eastern Hills.[88]

| Timeline of inhabitation of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia | |

|

.png.webp) |

Prehistory

The prehistorical period was characterised by the existence of a large Pleistocene glacial lake on the Bogotá savanna; Lake Humboldt, also called Lake Bogotá. This lake with an approximate surface area of 4,000 square kilometres (1,500 sq mi) covered the flatlands of the savanna to the northwest of the Eastern Hills. Surrounding the lake, Pleistocene megafauna as Cuvieronius (Tibitó and Mosquera),[89] Haplomastodon, Equus amerhippus, Glyptodonts and giant sloths, foraged. The lake contained an island, represented today by the Suba Hills, an elongated elevated area parallel to the Eastern Hills. Glaciers in the cold Late Pleistocene, known as the Last Glacial Maximum, existed until around 10,000 years BP in the southwestern parts, close to the Sumapaz Páramo.[90]

During this last cold phase of the Pleistocene, the Bogotá savanna became populated by the first humans, as evidenced by findings in El Abra (12,500 BP), Tibitó (11,740 BP) and Tequendama (11,000 BP).[91][92][93] These hunter-gatherers lived in rock shelters, collected food, and hunted animals mainly comprising white-tailed deer, little red brocket and guinea pigs.[75] White-tailed deer was the largest species—males: 50 kilograms (110 lb), females: 30 kilograms (66 lb)—hunted by the people, not only for the meat, but also to use the skins and bones.[94] The hunter-gatherers of these early lithic Abriense and Tequendamiense cultures used edge-trimmed flakes to process the skins and meat.[95]

Preceramic

During the first millennia of the Holocene, the inhabitants of the Andean plateaus and valleys gradually moved away from the rock shelters, settling in the open area. They constructed primitive living spaces of bones and skins, placed in a circle. Evidence for these rudimentary houses has been found at sites such as Aguazuque (Soacha) and Checua (Nemocón), respectively in the southern and northern part of the Bogotá savanna.[96][97] Some rock shelters continued to be inhabited; at Tequendama and Nemocón archaeological investigations have uncovered the continued presence of humans during the preceramic stage.[97] Early burial sites have been uncovered in all of the sites.[98]

Herrera Period

The name Herrera Period has been given to the stage following the preceramic, when agriculture became widespread and the use of ceramic common. Certain centres for the elaboration of pottery were present on the Altiplano; Zipaquirá, Mosquera, Ráquira and, possibly, productions by individual families and settlements.[99] Various regional classifications, up to starting at 1500 BCE,[100] for the Herrera Period exist across the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, with a commonly accepted definition lasting from 800 BCE to 800 AD.[101]

Archaeological evidence dated to the Herrera Period of sites surrounding the Eastern Hills has been found in Sopó,[102] Chía,[103] and Usme.[104]

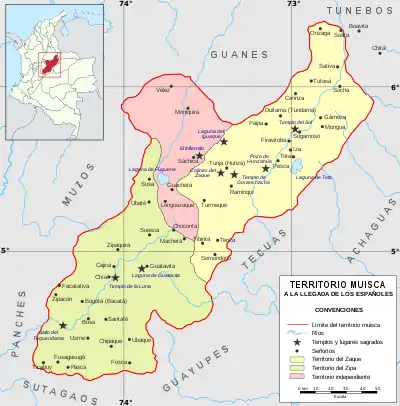

Muisca Confederation

The name Muisca Confederation has been given to the various small settlements, loosely organised in cacicazgos on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense and surrounding valleys, such as the Tenza Valley. The character of this "confederation" was different from the Inca and Aztec Empires as a central authority was not present.[105] The caciques were religious leaders who guarded the valleys of the Altiplano, caring for the subsistence economy of the people. The caciques did not control the production directly, although surpluses were distributed among them.[106] Trading was performed using salt, giving the Muisca the name "The Salt People".[107] The extraction of the high quality salt was the task of the Muisca women.[108] Other objects used for trade were small cotton cloths and larger mantles, and ceramics.[109] The eastern trade was dominated by the markets in Teusacá, Chocontá and Suesca.[110] The diet of the people consisted mostly of maize, tubers and potatoes; products of their rich agriculture, with protein sources white-tailed deer and the widely domesticated guinea pig.[111]

The area of the Eastern Hills was the boundary between the zipazgo of Bacatá, the cacicazgo of Guatavita, and the cacicazgo of Ebaqué, with the cacique based in a settlement in the present-day limits of Ubaque, named after this cacique.[112][113] The settlements bordering the western part of the Eastern Hills of Bacatá—not the name of a city, yet meaning "outside the farmfields" in the version of Chibcha spoken by the Muisca, Muysccubun—were formed by from north to south Usaquén, Teusaquillo, and Usme.[112] Those names are kept as the present-day localities of Bogotá.[114][115][116] The eastern and northeastern slopes of the Eastern Hills were populated in small settlements of Teusacá, Suaque, Sopó and Guasca, as evidenced by numerous archaeological finds.[113]

The forests of the Eastern Hills were considered sacred terrain in the Muisca religion, and temples were constructed to honour the main deities of the people; Chía (the Moon) and her husband Sué, the Sun.[85] The Muisca did not cut the trees of the divine forests, yet buried their deceased relatives there.[117] They also used the many creeks in the hills to traverse the mountains to reach their sacred lakes in pilgrimages, most notably those of Guatavita and Siecha.[118]

Spanish conquest (1537–1539)

The first Europeans who saw the Bogotá savanna and the Eastern Hills were the soldiers of conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada who participated in the quest for El Dorado. The period of conquest commenced when they reached the flatlands of the Bogotá savanna from the north. Although around 800 soldiers started the expedition, only 120 reached the inner Andes. They spent the Holy Week of 1537 in Chía, that was founded by the Granadian leader on March 24 after passing through Cajicá one day earlier.[119][120] From here, setting up camp on the Suba Hills on April 5, the conquistadors continued southwestward towards Bacatá or Muequetá, located in modern Funza, the main settlement of the zipa Tisquesusa.[121] The leader of the southern Muisca was defeated quickly and the Spanish set up their main camp in Bosa. Conquistador Pedro Fernández de Valenzuela was sent towards the site of Teusaquillo, where the zipa had a bohío (house). From Bosa, various expeditions on the Altiplano were organised during 1537 and early 1538. On August 6 of that year, the city of Santafé de Bogotá was officially founded as the capital of the New Kingdom of Granada.[119][121]

Colonial period (1539–1810)

1772.JPG.webp)

After the foundation of Santa Fe de Bogotá, the principal colonial settlement was concentrated in the present-day centre of the city with minor expansion on both sides of the San Francisco River. The growth of the city in the first centuries was hindered by the presence of the many wetlands and rivers on the Bogotá savanna.[122] One of the motives to establish the capital on the savanna was to take advantage of the favourably cool climate and fertility of the soil to grow the introduced Old World crop wheat.[123] The political organisation of the territories in what is known today as Colombia established encomiendas in which the indigenous people had to pay tributes to the encomenderos.[124] The Muisca were forced out of the most fertile grounds to live in less favourable areas, yet were obliged to work the good farmlands for the Spanish colonisers.[125]

The city of Santa Fe de Bogotá grew in the 18th and early 19th century, which increased the demand for wood for construction and as firewood. The main area of exploitation was the Eastern Hills, and when Alexander von Humboldt visited the area in the early 19th century, he noted "that there was not a single tree left until the open area of Choachí".[126]

Republican period (1810–1930)

The beginning of the Republican period of the Eastern Hills was marked by the independence of the Spanish Crown and the declaration of Santa Fe as capital of Gran Colombia. During this time, the higher classes of society left the colonial centre of the city and moved to higher elevations. The buildings constructed were dispersed, in contrast to the dense architecture of the colonial period. Haciendas were constructed in Usaquén, where hunting the white-tailed deer, then still abundant in the Eastern Hills, was common.[122] As of the second half of the 19th century, a process of reforesting the Eastern Hills with imported species as eucalyptus, cypress and acacias was started. The city itself saw the development of trains and the introduction of the telegraph.[126]

Modern period

The Eastern Hills were almost completely deforested in the 1930s and 1940s.[127] In those years, the presidency of Enrique Olaya Herrera marked a new era, during which Bogotá expanded with settlement farther away from the centre of the city, and the lower classes inhabited the slopes of the Eastern Hills and the southern part of the Bogotá savanna.[122] The electrification and the use of gas and cocinol (a type of gasoline used domestically) halted the process of deforestation and marked the spontaneous regrowth of vegetation in the Eastern Hills. The tumultuous end of the 1940s (Bogotazo) resulted in a more outspread settlement towards the north of Bogotá, away from the central areas of the city. This created a class difference with the richer households in the north and poverty in the south, a division that exists until today.[128] An important architect for the expansion and development of Bogotá in the 1930s and 1940s was Austrian Karl Brunner von Lehenstein.[129]

The sixties and seventies of the twentieth century were marked by urban development of the international business centre of Bogotá. During these decades the Torres Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, Torres de Fenicia, Torres Blancas, Torres del Parque and the Torre Colpatria, at that moment the highest building in Colombia, were constructed in the foothills of the Cerros Orientales.[130]

The end of the 1970s and early 1980s were characterised by an influx of migrants from other parts of Colombia, mainly people from Boyacá, Cundinamarca, Santander and Tolima, many of whom settled in Suba. In 1986, eighteen illicit residential neighbourhoods were created in the hills of Usaquén.[122] The tallest building of Colombia and second-tallest of South America, BD Bacatá, named after the capital area of the southern Muisca; Bacatá, has been scheduled to be completed in 2017.[131]

Environmental issues

Most of the Eastern Hills are a natural reserve, established in 1976.[132] The designation of an environmental code was proposed by Julio Carrizosa Umaña, who worked for the Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi.[133] Several studies have been done and proposals written to improve the environmental management of the Eastern Hills. A study, published in 2008, attempts to manage the area of quebrada Manzanares where loss of flora and fauna is one of the problems.[134] An investigation in 2009 showed that 90,000 people are living in the Eastern Hills.[135]

The invasive species Ulex europaeus (common gorse), an evergreen shrub that has been introduced in Colombia, highly affects the original ecology of the Eastern Hills. The species has been used to fight erosion since the 1950s,[136] but is prone to forest fires, with which it spreads its seeds.[137]

Mining

Mining is a common activity in the Eastern Hills. Although most of the area is a dedicated natural reserve, in 2009 sixty-two quarries existed within the reserve of the Eastern Hills.[135] The total surface of mining activities in 2006 was 120 hectares (300 acres), less than 1 percent of the total area of the Eastern Hills.[138] Extensive mining areas are in La Calera and Usme. The Soratama quarry, named after the indigenous Muisca woman Zoratama, in the northern part of the Eastern Hills, was used for decades until it was closed in 1990. During the 2000s and in recent years, the location of the former quarry has been destined for geomorphological restoration.[139]

Forest fires

Forest fires are a common threat to the vegetation of the Eastern Hills and the living spaces on the eastern slopes of the Colombian capital. Studies about the frequency of forest fires have revealed that most fires occur on Sundays, Mondays and Fridays. Periods of increased fire frequency are the drier months January, February, July, September and October.[2] A series of fires in January and February 2016 consumed 18 hectares (44 acres) of the forests close to the neighbourhoods Aguas Claras and La Selva of the locality San Cristóbal.[140] Later in the same month, more sources of forest fires were found.[141] During a forest fire in 2010, 30 hectares (74 acres) of wooded area was lost.[142] In 2015, eighteen forest fires were noted.[143] To extinguish the fires, helicopters with Bambi Buckets were used.[144] The forest fires, also occurring along the road towards La Calera, east of Chapinero, and in Usme, affected schools, universities, the National Congress, the Museo del Oro and Banco de la República, who suspended their activities.[145]

Fire Monserrate

Fire Monserrate

October 2015 Monserrate

Monserrate

2015 Monserrate

Monserrate

2015 Monserrate

Monserrate

2015 Burned forest

Burned forest

October 2013

Fire Monserrate

Fire Monserrate

October 2015 Monserrate

Monserrate

2015 Monserrate

Monserrate

2015 Monserrate

Monserrate

2015 Burned forest

Burned forest

October 2013

Tourism

The Eastern Hills have various tourist trails. The main trail, which ascends to the Monserrate monastery from La Candelaria, was for centuries a pilgrimage route for monks and nuns. The commonly used Teleférico de Monserrate was inaugurated in September 1955.[146] Other walking paths are along the La Vieja, Las Delicias and Las Moyas creeks in Chapinero.[147]

Panorama

See also

References

- 1 2 Peraza, 2011, p.57

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 (in Spanish) Cerros Orientales – Alcaldía Bogotá

- ↑ (in Spanish) Cerro Monserrate – official website

- ↑ (in Spanish) Cerro de Guadalupe

- ↑ Audiencia CAR, 2006, p.42

- ↑ Martínez Montoya, 2010, p.29

- ↑ Correa, 2005, p.213

- ↑ (in Spanish) uac - Muysccubun Dictionary online

- ↑ (in Spanish) ca - Muysccubun Dictionary online

- ↑ (in Spanish) ta - Muysccubun Dictionary online

- ↑ (in Spanish) Muyquytá - Muysccubun Dictionary online

- ↑ Epítome, p.85

- 1 2 3 4 5 Geological Map Bogotá, 1997

- ↑ Guerrero Uscátegui, 1992, p.4

- 1 2 3 4 Guerrero Uscátegui, 1992, p.5

- ↑ Villarroel, 1987, p.241

- ↑ Etayoa bacatensis at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ (in Spanish) Un xenungulado del Paleoceno de la Sabana de Bogotá – Paleontología en Colombia

- ↑ Stephania palaeosudamericana – Paleobiology Database

- ↑ Menispina evidens 1 – Paleobiology Database

- ↑ Menispina evidens 2 – Paleobiology Database

- 1 2 Guerrero Uscátegui, 1992, p.6

- ↑ Guerrero Uscátegui, 1996, p.12

- ↑ Guerrero Uscátegui, 1992, p.7

- ↑ Pérez Preciado, 2000, p.13

- 1 2 Pérez Preciado, 2000, p.14

- ↑ Velandia & De Bermoudes, 2002, p.42

- ↑ Velandia & De Bermoudes, 2002, p.43

- 1 2 3 Olaya et al., 2010

- ↑ Dengo & Covey, 1993, p.1318

- ↑ Villamil, 2012, p.164

- ↑ Caballero et al., 2013, p.15

- ↑ Caballero et al., 2013, p.16

- ↑ Caballero et al., 2013, p.17

- ↑ Caballero et al., 2013, p.18

- ↑ Caballero et al., 2013, p.19

- ↑ Caballero et al., 2013, p.20

- ↑ Parra et al., 2008, p.17

- ↑ Caballero et al., 2013, p.21

- ↑ De la Parra et al., 2015, p.1464

- ↑ Wheeler, 2010, p.132

- ↑ Caballero et al., 2013, p.22

- ↑ Mora et al., 2015, p.1589

- ↑ Galvis Vergara et al., 2006, p.502

- ↑ Torres et al., 2005, p.142

- ↑ Rutter et al., 2012, p.32

- ↑ Chicangana et al., 2014, p.78

- ↑ Montoya & Reyes, 2005, p.79

- ↑ Chicangana et al., 2014, p.84

- ↑ (in Spanish) A 15 ascienden los muertos que dejó temblor del sábado en el centro del país – El Tiempo

- ↑ Espinosa Baquero, 2004, p.1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Espinosa Baquero, 2004, p.4

- ↑ Dimaté & Arcila, 2006, p.13

- 1 2 Sarabia Gómez et al., 2010, p.154

- ↑ Gómez Capera et al., 2014, p.212

- ↑ Significant Earthquake – November 16, 1827 – NOAA

- ↑ Earthquake – August 31, 1917 – NOAA

- ↑ Significant Earthquake – May 24, 2008 – NOAA

- ↑ Martínez Hernández, 2006, p.35

- 1 2 3 4 5 Martínez Hernández, 2006, p.37

- ↑ Climate-data.org – La Calera

- ↑ Martínez Hernández, 2006, p.38

- 1 2 Isaza Londoño et al., 1999, p.28

- ↑ Isaza Londoño et al., 1999, p.29

- ↑ Cerros, s.a., p.27

- ↑ Ramírez Rodríguez et al., 2012, p.56

- ↑ Páramos.org, s.a., p.96

- ↑ Suna Hisca, s.a., p.335

- ↑ Pérez Preciado, 2000, p.24

- ↑ Cerros, s.a., p.25

- ↑ 1912 bird species in Colombia available online – ProAves.org

- ↑ Peraza, 2011, p.58

- ↑ Peraza, 2011, p.59

- 1 2 3 4 (in Spanish) Fauna of the Eastern Hills

- 1 2 Correal Urrego, 1990, p.79

- 1 2 3 (in Spanish) Biodiversidad y conservación – Cerros al oriente de Bogotá

- ↑ (in Spanish) Indignación: Cruel muerte de un oso de anteojos cerca a Chingaza - El Espectador

- ↑ Suna Hisca, s.a., p.339

- ↑ Mendoza R. & Rodríguez Barbosa, 2014, p.12

- ↑ "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. March 2007. March 2007. Retrieved 2018-10-28.

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2013, p.37

- ↑ (in Spanish) El Infiernito – Pueblos Originarios

- ↑ Bonilla Romero, 2011

- ↑ Bonilla Romero et al., 2017, p.153

- 1 2 Isaza Londõno et al., 1999, p.35

- ↑ Izquierdo Peña, 2009, p.86

- ↑ Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 1:09:00

- ↑ Friede, 1960, pp.69–78

- ↑ Prado et al., 2003, p.353

- ↑ Pérez Preciado, 2000, p.7

- ↑ (in Spanish) Nivel Paleoindio. Abrigos rocosos del Tequendama

- ↑ Gómez Mejía, 2012, p.153

- ↑ Botiva Contreras et al., 1989

- ↑ Martínez Polanco, 2011, p.105

- ↑ Dillehay, 1999, p.210

- ↑ Correal Urrego, 1990, pp.237–244

- 1 2 Groot de Mahecha, 1992, p.64

- ↑ Rivera Pérez, 2013, p.74

- ↑ De Paepe & Cardale de Schrimpff, 1990, p.106

- ↑ Langebaek, 1995, p.70

- ↑ (in Spanish) Chronology of pre-Columbian periods: Herrera and Muisca

- ↑ (in Spanish) Herrera Period evidence in Sopó

- ↑ Cardale de Schrimpff, 1985, p.104

- ↑ (in Spanish) Herrera Period evidence in Usme – El Tiempo

- ↑ Gamboa Mendoza, 2016

- ↑ Kruschek, 2003, p.12

- ↑ Daza, 2013, p.22

- ↑ Groot de Mahecha, 2014, p.14

- ↑ Francis, 1993, p.44

- ↑ Francis, 1993, p.39

- ↑ García, 2012, p.122

- 1 2 Herrera Ángel, 2006, p.126

- 1 2 Isaza Londoño et al., 1999, p.33

- ↑ (in Spanish) Etymology localities of Bogotá

- ↑ (in Spanish) Etymology Usaquén

- ↑ (in Spanish) Etymology Usme – El Tiempo

- ↑ Epítome, p.94

- ↑ Isaza Londoño et al., 1999, p.37

- 1 2 (in Spanish) Conquista rápida y saqueo cuantioso de Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada

- ↑ (in Spanish) History Cajicá

- 1 2 (in Spanish) Bogotá: de paso por la capital – Banco de la República

- 1 2 3 4 (in Spanish) Historia de Usaquén

- ↑ Camargo Ponce de León, s.a., p.3

- ↑ Camargo Ponce de León, s.a., p.4

- ↑ Camargo Ponce de León, s.a., p.5

- 1 2 Camargo Ponce de León, s.a., p.6

- ↑ Camargo Ponce de León, s.a., p.7

- ↑ Camargo Ponce de León, s.a., p.8

- ↑ (in Spanish) La gran herencia – Semana

- ↑ Rincón Avellaneda, 2006, p.129

- ↑ BD Bacatá

- ↑ Audiencia CAR, 2006, p.4

- ↑ (in Spanish) La historia de Carrizosa, un 'custodio' de los cerros orientales – El Tiempo

- ↑ García Rueda et al., 2008, p.9

- 1 2 Gómez Lee, 2009, p.226

- ↑ Aguilar Garavito, 2010, p.13

- ↑ Aguilar Garavito, 2010, p.12

- ↑ Audiencia CAR, 2006, p.45

- ↑ (in Spanish) Canteras que desangran a los cerros orientales - El Tiempo

- ↑ (in Spanish) Ascienden a 18 las hectáreas consumidas por el fuego en los cerros – El Tiempo

- ↑ (in Spanish) Sobrevuelo confirma tres columnas de humo en los cerros – El Tiempo

- ↑ Aguilar Garavito, 2010, p.14

- ↑ (in Spanish) Incendio en cerros orientales de Bogotá está controlado en un 70% – El Espectador

- ↑ (in Spanish) Serían cinco las hectáreas afectadas por incendio en cerros orientales de Bogotá – El Espectador

- ↑ (in Spanish) Centro de Bogotá en alerta por incendio en cerros orientales – El Espectador

- ↑ (in Spanish) Teleférico de Monserrate

- ↑ Monroy & Pretelt, 2015, p.12

Bibliography

General

- Isaza Londoño, Juan Luis; Diana Wiesner Ceballos; Camilo Salazar Ferro; Juan Pablo Ortiz Suárez, and Catalina Useche Mariño. 1999. Los cerros: paisaje e identidad cultural – Identificación y valoración del patrimonio ambiental y cultural de los cerros orientales en Santa Fe de Bogotá, 1–124. CIFA, Universidad de los Andes. Accessed 2017-01-10. Archived 2017-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Monroy Hernández, Julieth, and Carlos Pretelt. 2015. Paisaje y territorio en los cerros orientales de Bogotá: una mirada a la red de senderos. GeoAndes _. 1–14. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Nieto Escalante, Juan Antonio; Claudia Inés Sepulveda Fajardo; Luis Fernando Sandoval Sáenz; Ricardo Fabian Siachoque Bernal; Jair Olando Fajardo Fajardo; William Alberto Martínez Díaz; Orlando Bustamante Méndez, and Diana Rocio Oviedo Calderón. 2010. Geografía de Colombia – Geography of Colombia, 1–367. Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi.

- Ramírez Hernández, Héctor Andrés; Claudia Inés Mesa Betancourt; Catalina García Barón, and Rodrigo Valero Garay. 2015. ¡Así se viven los cerros! – Experiencias de habitabilidad, 1–151. Alcaldía de Bogotá. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Suárez R., Maurix. 1999. Los cerros: paisaje e identidad cultural – mapa – escala 1:120,000, 1. CIFA, Universidad de los Andes. Accessed 2017-01-10. Archived 2011-12-15 at the Wayback Machine

- N., N. s.a. Atlas de Páramos de Colombia – Cordillera Oriental – Distrito Páramos de Cundinamarca – Complejo Cruz Verde-Sumapaz, 96–99. Accessed 2017-01-10.

Geology

- Caballero, Victor M.; Andrés Reyes Harker; Andrés Mora; Carlos F. Ruiz, and Felipe de la Parra. 2013. Cenozoic Paleogeographic Reconstruction of the Foreland System in Colombia and Implications on the Petroleum Systems of the Llanos Basin, 1–24. AAPG International Conference, Cartagena, Colombia.

- Chicangana, Germán; Carlos Alberto Vargas Jiménez; Andreas Kammer; Alexander Caneva; Elkin Salcedo Hurtado, and Augusto Gómez Capera. 2015. La amenaza sísmica de la Sabana de Bogotá frente a un sismo de magnitud M > 7.0, cuyo origen esté en el Piedemonte Llanero. Revista Colombiana de Geografía 24. 73–91. .

- Dengo, Carlos A., and Michael C. Covey. 1993. Structure of the Eastern Cordillera: Implications for Trap Styles and Regional Tectonics. AAPG Bulletin 77. 1315–1337. .

- Dimaté, Cristina, and Mónica Arcila. 2006. Amenaza sísmica sobre Bogotá: ¿leyenda o realidad?. Innovación y Ciencia XIII. 11–15. Accessed 2017-01-12.

- Espinosa Baquero, Armando. 2004. Historia Sísmica de Bogotá, 1–10. Sociedad Geográfica de Colombia. Accessed 2017-01-12.

- Espinosa Baquero, Armando. 2003. La sismicidad histórica en Colombia – Historical seismicity in Colombia. Revista Geográfica Venezolana 44. 271–283. Accessed 2017-01-12.

- Galvis Vergara, Jaime; Ricardo De la Espriella, and Ricardo Cortés Delvalle. 2006. Vulcanismo cenozoico en la Sabana de Bogotá. Ciencias de la Tierra 30. 495–502. .

- Gómez, J.; N.E. Montes; Á. Nivia, and H. Diederix. 2015. Plancha 5-09 del Atlas Geológico de Colombia 2015 – escala 1:500,000, 1. Servicio Geológico Colombiano. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Gómez Capera, Augusto Antonio; Elkin de Jesús Salcedo Hurtado; Dino Bindi; José Enrique Choy, and Julio Antonio García Peláez. 2014. Localización y magnitud del terremoto de 1785 en Colombia calculadas a partir de intensidades macrosísmicas. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 38. 206–217. Accessed 2016-01-12.

- Guerrero Uscátegui, Alberto Lobo. 1996. Estratigrafía del material no-consolidado en el subsuelo del nororiente de Santafé de Bogotá (Colombia) con algunas notas sobre historia geológica, 1–23. VII Congreso Colombiano de Geología.

- Guerrero Uscátegui, Alberto Lobo. 1992. Geología e Hidrogeología de Santafé de Bogotá y su Sabana, 1–20. Sociedad Colombiana de Ingenieros.

- Montoya Arenas, Diana María, and Germán Alfonso Reyes Torres. 2005. Geología de la Sabana de Bogotá, 1–104. INGEOMINAS.

- Mora, Andrés; Wilson Casalles; Richard A. Ketcham; Diego Gómez; Mauricio Parra; Jay Namson; Daniel Stockli; Ariel Almendral, and Wilmer Robles. 2015. Kinematic restoration of contractional basement structures using thermokinematic models: A key tool for petroleum system modeling. AAPG Bulletin 99. 1575–1598. .

- Olaya, Angela; Cristina Dimaté, and Kim Robertson. 2010. ¿Fallamiento activo en la Cordillera Oriental al suroeste de Bogotá, Colombia? – Is there active faulting in the Eastern Cordillera southwest of Bogotá, Colombia?. Geología Colombiana 35. 58–73. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Parra, Felipe de la; Andrés Mora; Milton Rueda, and Isaid Quintero. 2015. Temporal and spatial distribution of tectonic events as deduced from reworked palynomorphs in the eastern Northern Andes. AAPG Bulletin 99. 1455–1472. .

- Parra, Mauricio; Andrés Mora; Edward R. Sobel; Manfred R. Strecker; Carlos Jaramillo; Paul B. O'Sullivan, and Román González. 2008. Cenozoic Orogenic Growth of the North Andes: Shortening and Exhumation Histories of the Eastern Cordillera of Colombia, 1–27. AAPG Annual Convention, San Antonio, Texas.

- Rutter, N.; A. Coronato; K. Helmens; J. Rabassa, and M. Zárate. 2012. Glaciations in North and South America from the Miocene to the Last Glacial Maximum, 1–67. Springer.

- Sarabia Gómez, Ana Milena; Hernán Guillermo Cifuentes Avendaño, and Kim Robertson. 2010. Análisis histórico de los sismos ocurridos en 1785 y en 1917 en el centro de Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Geografía 19. 153–162. Accessed 2016-01-12.

- Torres, Vladimir; Jeff Vandenberghe, and Henry Hooghiemstra. 2005. An environmental reconstruction of the sediment infill of the Bogotá basin (Colombia) during the last 3 million years from abiotic and biotic proxies. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 226. 127–148. .

- Velandia Patiño, F.A., and O. De Bermoudes. 2002. Fallas longitudinales y transversales de la Sabana de Bogotá, Colombia. Boletín de Geología 24. 37–48. .

- Villamil, Tomas. 2012. Chronology Relative Sea Level History and a New Sequence Stratigraphic Model for Basinal Cretaceous Facies of Colombia, 161–216. Society for Sedimentary Geology (SEPM).

- Villarroel A., Carlos. 1987. Características y afinadas de Etayoa n. gen., tipo de una nueva familia de Xenungulata (Mammalia) del Paleoceno Medio (?) de Colombia. Comunicaciones Paleontológicas del Museo de Historia Natural de Montevideo 19. 241–254. Accessed 2017-03-29.

- Various, Authors. 1997. Mapa geológico de Santa Fe de Bogotá – Geological Map Bogotá – escala 1:50,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Wheeler, Brandon. 2010. Community ecology of the Middle Miocene primates of La Venta, Colombia: the relationship between ecological diversity, divergence time, and phylogenetic richness. Primates 51.2. 131–138. .

Flora and fauna

- Cantillo Higuera, Edgard E., and Melisa Gracia Cuéllar. 2013. Diversidad y caracterización florística de la vegetación natural en tres sitios de los cerros orientales de Bogotá D. C.. Colombia Forestal 16. 228–256. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Martínez Polanco, María Fernanda. 2011. La biología de la conservación aplicada a la zooarqueología: la sostenibilidad de la cacería del venado cola blanca, Odocoileus virginianus (Artiodactyla, Cervidae), en Aguazuque. Antipoda 13. 99–118. .

- Mendoza R., Juan Salvador, and Camila Rodríguez Barbosa. 2014. Saurios en los Andes: historia natural de la comunidad de lagartijas de los cerros orientales de Bogotá, 11–13. Universidad de los Andes. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Peraza, Camilo A.. 2011. Aves, Bosque Oriental de Bogotá Protective Forest Reserve, Bogotá, D.C., Colombia. Journal of species lists and distribution 7. 57–63. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Pérez Preciado, Alfonso. 2000. La estructura ecológica principal de la Sabana de Bogotá, 1–37. Sociedad Geográfica de Colombia.

- Ramírez Rodríguez, Carlos René; Christian Hernán Duarte Colmenares, and Jacinto Orlando Galeano Ardila. 2012. Estudio de suelos y su relación con las plantas en el páramo el Verjón ubicado en el municipio de Choachí, Cundinamarca. Revista de Investigación 6. 56–72. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- N., N. s.a. Parque Ecológico Distrital de Montaña Entrenubes – Tomo I – Componente Biofísico – Fauna-Anfibios y Reptiles, 334–370. Corporación Suna Hisca.

- N., N. s.a. Los cerros, una reserva natural, 22–27. Accessed 2017-01-10.

History

- Camargo Ponce de León, Germán. s.a. Historia pintoresca y las perspectivas de ordenamiento de los Cerros Orientales de Santa Fe de Bogotá, 1–16. Accessed 2017-01-10.

Prehistory

- Dillehay, Tom M. 1999. The Late Pleistocene Cultures of South America. Evolutionary Anthropology _. 206–216. .

- Prado, José Luis; María Teresa Alberdi; Begoña Sánchez, and Beatriz Azanza. 2003. Diversity of the Pleistocene Gomphotheres (Gomphotheriidae, Proboscidea) from South America. Deinsea, Natural History Museum Rotterdam 9. 347–364. .

Preceramic and Herrera

- Botiva Contreras, Álvaro; Ana María Groot de Mahecha; Eleonor Herrera, and Santiago Mora. 1989. Colombia Prehispánica – La Altiplanicie Cundiboyacense – Prehispanic Colombia – the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. Biblioteca Luís Ángel Arango. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Cardale de Schrimpff, Marianne. 1985. En busca de los primeros agricultores del Altiplano Cundiboyacense – Searching for the first farmers of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, 99–125. Banco de la República. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo. 1990. Aguazuque – evidencias de cazadores, recolectores y plantadores en la altiplanicie de la Cordillera Oriental – Aguazuque: Evidence of hunter-gatherers and growers on the high plains of the Eastern Ranges, 1–316. Banco de la República: Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas Nacionales. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Gómez Mejía, Juliana. 2012. Análisis de marcadores óseos de estrés en poblaciones del Holoceno Medio y Tardío incial de la sabana de Bogotá, Colombia – Analysis of bone stress markers in populations of the Middle and Late Holocene of the Bogotá savanna, Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Antropología 48. 143–168. .

- Groot de Mahecha, Ana María. 1992. Checua: Una secuencia cultural entre 8500 y 3000 años antes del presente – Checua: a cultural sequence between 8500 and 3000 years before present, 1–95. Banco de la República. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 1995. Arqueología Regional en el Territorio Muisca: Juego de Datos del Proyecto Valle de Fúquene – Regional Archaeology in the Muisca Territory: A Study of the Fúquene and Susa Valleys, 1–215. Center for Comparative Arch, University of Pittsburgh. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Paepe, Paul de, and Marianne Cardale de Schrimpff. 1990. Resultados de un estudio petrológico de cerámicas del Periodo Herrera provenientes de la Sabana de Bogotá y sus implicaciones arqueológicas – Results of a petrological study of ceramics form the Herrera Period coming from the Bogotá savanna and its archaeological implications. Boletín Museo del Oro _. 99–119. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Rivera Pérez, Pedro Alexander. 2013. Uso de fauna y espacios rituales en el precerámico de la sabana de Bogotá – Use of fauna and ritual spaces in the preceramic of the Bogotá savanna. Revista ArchaeoBIOS 7-1. 71–86. .

Muisca

- Bonilla Romero, Julio H.; Edier H. Bustos Velazco, and Jaime Duvan Reyes. 2017. Arqueoastronomía, alineaciones solares de solsticios y equinoccios en Bogotá-Bacatá – Archaeoastronomy, alignment solar from solstices and equinoxes in Bogota-Bacatá. Revista Científica, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas 27. 146–155. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Bonilla Romero, Julio H. 2011. Aproximaciones al observatorio solar de Bacatá-Bogotá-Colombia – Approaches to solar observatory Bacatá-Bogotá-Colombia. Azimut, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas 3. 9–15. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Daza, Blanca Ysabel. 2013. Historia del proceso de mestizaje alimentario entre Colombia y España – History of the integration process of foods between Colombia and Spain (PhD), 1–494. Universitat de Barcelona.

- Francis, John Michael. 1993. "Muchas hipas, no minas" The Muiscas, a merchant society: Spanish misconceptions and demographic change (M.A.), 1–118. University of Alberta.

- Gamboa Mendoza, Jorge. 2016. Los muiscas, grupos indígenas del Nuevo Reino de Granada. Una nueva propuesta sobre su organizacíon socio-política y su evolucíon en el siglo XVI – The Muisca, indigenous groups of the New Kingdom of Granada. A new proposal on their social-political organization and their evolution in the 16th century. Museo del Oro. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- García, Jorge Luis. 2012. The Foods and crops of the Muisca: a dietary reconstruction of the intermediate chiefdoms of Bogotá (Bacatá) and Tunja (Hunza), Colombia (M.A.), 1–201. University of Central Florida. Accessed 2017-05-13.

- Groot de Mahecha, Ana María. 2014 (2008). Sal y poder en el altiplano de Bogotá, 1537–1640, 1–174. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- Izquierdo Peña, Manuel Arturo. 2014. Calendario Muisca – Muisca calendar. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Izquierdo Peña, Manuel Arturo. 2009. The Muisca Calendar: An approximation to the timekeeping system of the ancient native people of the northeastern Andes of Colombia (PhD), 1–170. Université de Montréal. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Kruschek, Michael H.. 2003. The evolution of the Bogotá chiefdom: A household view (PhD), 1–271. University of Pittsburgh. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Londoño Laverde, Eduardo. 2001. El proceso de Ubaque de 1563: la última ceremonia religiosa pública de los muiscas – The trial of Ubaque of 1563: the last public religious ceremony of the Muisca. Boletín Museo del Oro 49. 49–101. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Ocampo López, Javier. 2013. Mitos y leyendas indígenas de Colombia – Indigenous myths and legends of Colombia, 1–219. Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A..

Spanish conquest

- Friede, Juan. 1960. Descubrimiento del Nuevo Reino de Granada y Fundación de Bogotá (1536–1539), 1–342. Banco de la República. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Herrera Ángel, Marta. 2006. Transición entre el ordenamiento territorial prehispánico y el colonial en la Nueva Granada. Historia Crítica 32. 118–152. .

- N, N. 1979 (1889) (1539). Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada, 81–97. Banco de la República. Accessed 2017-01-10.

Environmental issues

- Aguilar Garavito, Mauricio. 2010. Restauración ecológica de áreas afectadas por Ulex europaeus L. (MSc.), 1–75. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Audiencia, CAR. 2006. Los cerros orientales de Bogotá D.C. – Patrimonio cultural y ambiental del Distrito Capital, la región y el país – Plan de manejo ambiental, 1–116. Alcaldía Bogotá.

- Bohórquez Alfonso, Yvonne Alexandra. 2008. De arriba para abajo: la discusión de los cerros orientales de Bogotá, entre lo ambiental y lo urbano. Cuadernos de Vivienda y Urbanismo 1. 124–145. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- García Rueda, Adriana Milena; Gina Lizeth Lancheros, and Marcelo Bedoya Ortega. 2008. Propuesta de plan de manejo ambiental para la recuperación de la ronda hídrica de la Quebrada Manzanares a través de elementos naturales y arquitectónicos – Proposal of an environmental management plan for the improvement of the Manzanares Brook's hydric habitat by means of utilising natural and architectural elements, 1–12. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Gómez Lee, Iván Darío. 2009. Conflictos entre los derechos a la propiedad y el medio ambiente en los Cerros Orientales de Bogotá y la inseguridad jurídica. Revista Digital de Derecho Administrativo 2. 223–246. Accessed 2017-01-10.

- Martínez Hernández, Juber. 2006. Plan anual de estudios - PAE 2006 - Asegurar el futuro de los Cerros Orientales de Bogotá - Mandato Verde, 1–219. Contraloría de Bogotá. Accessed 2017-04-04.

- Rincón Avellaneda, Patricia. 2006. Bogotá y sus modalidades de ocupación del suelo: análisis de los procesos de re-densificación, 1–229. Universidad Nacional. Accessed 2017-01-10.

External links

- (in Spanish) Fundación Cerros de Bogotá – official website

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)