The eastern woodlands of the United States covered large portions of the southeast side of the continent until the early 20th century. These were in a fire ecology of open grassland and forests with low ground cover of herbs and grasses.

The frequent fires which maintained the woodlands were started by the region's many thunderstorms and Native Americans, with most fires burning the forest understory and not affecting the mature trees above. Before the arrival of humans about 15,000 years ago, lightning would have been the major source of ignition, the region having the most frequent wind and lightning storms in North America.[1][2][3][4] The European settlers who displaced the natives blended the local use of fire with their customary use of fire as pastoral herdsmen in the British Isles, Spain, and France.[1]

In the southern pine savanna, each area burned about every 1–4 years; after settlers arrived burning happened about every 1–3 years. In oak–hickory areas, estimates range from 3 to 14 years, although trails were kept open with fire.[1]

Prehistoric southeastern flora

Of all the United States, southeastern flora has been least changed in composition during the last 20,000 years. During the Last Glacial Maximum about 18,000 years ago, when the glacial front extended south to the approximate location of the Ohio River, preexisting natural communities in the Southeast remained largely intact. As a result, the Southeast contains a high level of endemism and genetic diversity as would be expected of an old flora.[5] Temperate deciduous forests dominated from about 33° to 30° N. latitude, including most of the glacial Gulf Coast from about 84° W. longitude. The coastline later changed during glacial melt, both in the Mississippi River valley and sea level rise of 130 meters (430 ft). Regional climate was similar to or slightly drier than modern conditions. Oak, hickory, chestnut, and southern pine species were abundant. Walnuts, beech, sweetgum, alder, birch, tulip tree, elms, hornbeams, tilias, and others that are generally common in modern southern deciduous forests were also common then. Grasses, sedges, and sunflowers were also common. Extensive mesophytic forest communities, similar to modern lowland and bottomland forests, occurred along major river drainages, especially the Mississippi embayment, the Alabama-Coosa-Tallapoosa Basin, the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint Basin, and the Savannah River Basin.[6]

Humans arrived as five thousand years passed following the retreat of the glaciers, while deciduous forests expanded northward throughout the region. Pockets of boreal elements remained only at high elevations in the Appalachian Mountains and in a few other refuges. Broadleaf evergreen and pine forests occupied an extent similar to their current one, primarily in the Atlantic Coastal Plain. Mesophytic and bottomland forest communities continued to occupy the major river drainages of the region.[6]

Although the major modern community types were flourishing in the Southeast by 10,000 years BP, and the climate was similar to that today, the understory flora had not yet come to resemble modern herbaceous floras. Mixed hardwood forests dominated the majority of the upper Coastal Plains, Piedmont, and lower mountain regions. Southern pine communities dominated the middle and lower Coastal Plains, whereas evergreens and some remnant boreal elements occupied higher elevation sites. There were few canopy openings in the mixed hardwood and high-elevation forest.[6]

Warming and drying during the Holocene climatic optimum began about 9,000 years ago and affected the vegetation of the Southeast. Extensive expansions of prairies and woody grasslands occurred throughout the region, and xeric oak and oak-hickory forest types proliferated. Cooler-climate species migrated northward and upward in elevation; many vanished from the region during this period while others were limited to isolated refuges. This retreat caused a proportional increase in pine-dominated forests in the Appalachians. The grassy woodlands of the time expanded and were also linked to the great interior plains grasslands to the west of the region. As a result, elements of the prairie flora became established throughout the region, first by simple migration, but then also by invading disjunct openings (including glades and barrens) that were forming in the canopy of more mesic forests.[6]

During most of the climatic shifts of the last 100,000 years, most plant migration in Eastern North America occurred along a more or less north-south axis. The climate optimum was significant because it made conditions favorable for the invasion and establishment of species from the center of the continent.[6]

After the end of the optimum about 5,000 years BP, as the climate cooled and precipitation increased, species migrated so that communities were reassembled in new forms in which all of the components of the modern southern forests were in place. The boreal forests of the early Quaternary enjoyed a modest expansion. Riparian, bottomland, and wetland plant communities expanded. The grassy woodlands contracted and retracted westward.[6]

At about 4,000 years BP, the Archaic Indian cultures began practicing agriculture throughout the region. Technology had advanced to the point that pottery was becoming common, and the small-scale felling of trees became feasible. Concurrently, the Archaic Indians began using fire in a widespread manner in large portions of the region. Intentional burning of vegetation was taken up to mimic the effects of natural fires that tended to clear forest understories, thereby making travel easier and facilitating the growth of herbs and berry-producing plants that were important for both food and medicines.[6]

For reasons that are unclear, approximately 500 years ago, aboriginal populations declined significantly throughout Eastern North America and more broadly throughout the Americas. … Thus, by the time the first European observers were reporting the nature of the vegetation of the region, it is likely to have changed significantly since the regional peak of Indian influence. A myth has developed that prior to European culture the New World was a pristine wilderness. In fact, the vegetation conditions that the European settlers observed were changing rapidly because of aboriginal depopulation. As a result, canopy closure and forest tree density were increasing throughout the region.[6]

Recent history

The oak-hickory forest of the Northeast was primarily burned by Native Americans, resulting in oak openings, barrens, and prairies in the Northeast and the Piedmont of North Carolina. There was nearly annual burning throughout the Northeast.[7] After the death of 90% of the native population around 500 years ago, grasslands, savanna, and woodlands succeeded to closed forest. After European settlement of the region the burning frequency was 2–10 years, with many sites burned annually.[1][6][7] The practice was so common that a North Carolina law in the early 18th century required annual burning of pastures and rangelands every March.[1]

In the southeast, longleaf pine dominated the savanna and open-floored forests which once covered 92,000,000 acres (370,000 km2) from Virginia to Texas. These covered 36% of the region's land and 52% of the upland areas. Of this, less than 1% of the unaltered forest still stands.[8]

Savannas typically contained grasses that were 3–6 feet (1–2 m) high.[1]

The southeast also had the Black Belt prairie region, within which was the blackland prairie, a type of tallgrass prairie.[8] Much of the Black Belt region was open space. As late as the 1830s, about 11% of the Black Belt region was covered with prairies.[9]

The largest prairie area in the southern Atlantic coastal plain was in the Florida panhandle region, from the Ochlockonee River to Louisiana's Florida Parishes[8]

Woodland elimination

The English colonists harvested the longleaf pine lumber, finding many uses for it. The slow-maturing tall straight trees were particularly suitable for shipbuilding and masts, although the lumber and pitch were widely used. The keel of USS Constitution was made from a single longleaf pine log. King George II decreed that straight pines over 24 inches (610 mm) in diameter were the king's property, but the colonists protested by tarring and feathering the official surveyors. However, harvesting was rather limited until 1900.[10]

At the start of the 20th century, heavy cutover of the southern pine forest, combined with longleaf pine seedling destruction by foraging livestock, eliminated pine regeneration.[1][10] As reflected by the 1924 federal Clarke–McNary Act, fire suppression began to be practiced. The American Forestry Association's "Dixie Crusaders" told the South that burning woods were bad.[1][11] The paper industry encouraged growth of loblolly and slash pines. The probability of catastrophic high-intensity fire increased as dead fuels increased on the forest floor. Overgrowth shades and stunts longleaf pine seedlings, undergrowth increases, and succession creates the southern mixed hardwood forest where savanna used to be. Intentional use of fire to manage vegetation began to be accepted again after World War II, and at present about 6,000,000 acres (24,000 km2) a year are burned.[1]

Remaining examples

The ecosystem of over 98% of eastern woodland areas such as longleaf pine have declined.[12]

Remaining grassy woodland and prairie cover some of the land in the following locations:

- Grand Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Alabama[8]

- Old Cahawba Prairie, Alabama[13]

- Apalachicola National Forest, Florida[8]

- Garcon Point, Florida[8]

- Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park, Florida[14]

- Paynes Prairie Preserve State Park, Florida[15]

- Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge, Georgia[8]

- Grand Bay Wildlife Management Area, Georgia[8]

- Coosa Valley Prairies, Georgia[16]

- Kisatchie National Forest, Louisiana[17]

- Soldiers Delight Natural Environment Area, Maryland[18]

- Gautier, Mississippi[8]

- Harrell Prairie Botanical Area, Mississippi[19]

- Pine Barrens, New Jersey[20]

- Croatan National Forest, North Carolina[21]

- Holly Shelter Game Land, North Carolina[22]

- Angola Bay Game Land, North Carolina[22]

- Green Swamp Preserve, North Carolina[23]

- Weymouth Woods-Sandhills Nature Preserve, North Carolina

- Boiling Spring Lakes Preserve, North Carolina[24]

- Sand Hills State Forest, South Carolina[25]

- Angelina National Forest, Texas[26]

- Sabine National Forest, Texas[27]

- Big Woods State Forest, Virginia[28]

- Piney Grove Preserve, Virginia[29]

The largest contiguous remaining pine savanna habitat is at

- Blackwater River State Forest, Florida, Conecuh National Forest, Alabama, and Eglin Air Force Base, Florida[8]

Flora

Members of the Northeast upland oak communities:

- Trees

- Invasive hardwoods in disrupted fire regimes

Growing in the southeast pine forest:

- Trees

- Loblolly pine (wetter sites)[1]

- Longleaf pine[1][8]

- Pond pine (wetter sites)[1]

- Sand pine (drier sites)[1]

- Shortleaf pine (drier sites)[1]

- Slash pine (wetter sites)[1][8]

- Virginia pine (drier sites)[1]

- Grasses

- Cane (canebrakes along streams)[30]

- Little bluestem (central Alabama westward)[1]

- Slender bluestem (central Alabama westward)[1]

- Wiregrass (Atlantic seaboard)[1]

- Woody understory

Exotics promoted by fire:

Fauna

Fauna which lived in the southeastern savanna include:

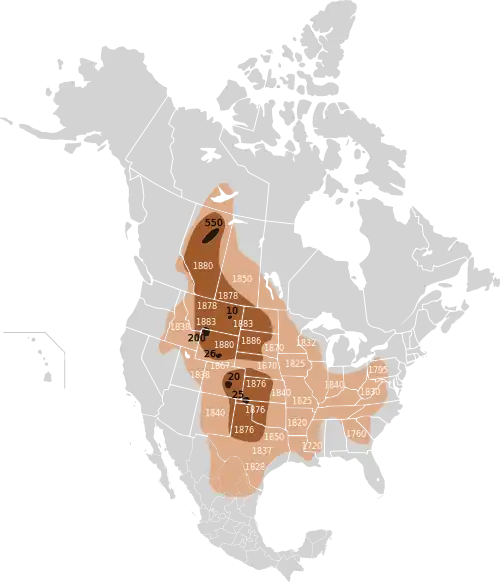

- Plains bison (circa 1550-1880)[30][31][32]

- Bachman's sparrow[8]

- Brown-headed cowbird[8]

- Brown-headed nuthatch[8]

- Southeastern fox squirrel (Sciurus niger niger)[8]

- White-tailed deer[30]

- Elk[30]

- Flatwoods salamanders[8]

- Gopher frog[8]

- Gopher tortoise[8]

- Henslow's sparrow (winter only)[8]

- Indigo snake[8]

- Loggerhead shrike[8]

- Northern bobwhite[8]

- Northern prairie warbler (Setophaga discolor discolor) - neotropical migrant[8]

- Red-cockaded woodpecker[8]

- Southeastern American kestrel (Falco sparverius paulus)[8]

- Red wolf[30]

- American black bear[30]

- North American cougar[30]

Living in prairie habitats:

- Eastern meadowlark[8]

- Florida sandhill crane (Grus canadensis pratensis)[8]

- Savannah sparrow[8]

In northeastern savanna:

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 Brown, James K.; Smith, Jane Kapler (2000). "Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on flora". Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. pp. 56–68. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ↑ Earley, Lawrence S. (2006). Looking for Longleaf: The Fall And Rise of an American Forest. UNC Press. ISBN 0-8078-5699-1.

- ↑ "Use of Fire by Native Americans". The Southern Forest Resource Assessment Summary Report. Southern Research Station, USDA Forest Service. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ↑ Williams, Gerald W. (June 12, 2003). "REFERENCES ON THE AMERICAN INDIAN USE OF FIRE IN ECOSYSTEMS" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 9, 2003. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ↑ Loehle, C. (2007). "Predicting Pleistocene climate from vegetation in North America" (PDF). Climate of the Past. 3 (1): 109–118. doi:10.5194/cp-3-109-2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Owen, Wayne (2002). "Chapter 2 (TERRA–2): The History of Native Plant Communities in the South". Southern Forest Resource Assessment Final Report. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- 1 2 Thompson, Daniel Q.; Ralph H. Smith (1971). "The Forest Primeval in the Northeast - A Great Myth?". Proceedings Annual Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Tallahassee, Florida: Tall Timbers Research Station. 10: 260.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Hunter, William C.; Lori H. Peoples; Jaime A. Collazo (May 2001). "Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan for The South Atlantic Coastal Plain (Physiographic Area 03)" (PDF). pp. 10–12, 63–64. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 17, 2008. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ↑ Barone, John A. (September 20, 2005). "Historical Presence and Distribution of Prairies in the Black Belt of Mississippi and Alabama". Castanea. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society. 70 (3): 170–183. doi:10.2179/04-25.1. ISSN 0008-7475. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- 1 2 GOBER, JIM R. "Products of the Longleaf Pine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2006. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ↑ Biswell, Harold; James Agee (1999). Prescribed Burning in California Wildlands Vegetation Management. University of California Press. p. 86. ISBN 0-520-21945-7.

- ↑ Noss, Reed F.; Edward T. LaRoe III; J. Michael Scott. "Endangered Ecosystems of the United States: A Preliminary Assessment of Loss and Degradation". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Old Cahawba Prairie | Forever Wild". www.alabamaforeverwild.com. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Florida State Parks". www.floridastateparks.org. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Florida State Parks". www.floridastateparks.org. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Tallgrass prairies in Georgia are rich in diversity". myajc. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ↑ "History & Culture". fs.usda.gov. United States Forest Service. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ↑ "Soldiers Delight Natural Environment Area". dnr.maryland.gov. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Harrell Prairie Hill Botanical Area - Mississippi Land Conservation Assistance Network". Mississippi Land Conservation Assistance Network. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Pine Barrens, New Jersey Pinelands Protection - Pinelands Preservation Alliance - Savannas". www.pinelandsalliance.org. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Restoration of Longleaf Pine Ecosystems". www.srs.fs.usda.gov. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- 1 2 Staff, Ashley Morris StarNews. "On the Map: Holly Shelter Game Land a haven for outdoor enthusiasts". Wilmington Star News. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Green Swamp Preserve | The Nature Conservancy". www.nature.org. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Boiling Spring Lakes Preserve | The Nature Conservancy". www.nature.org. Archived from the original on May 17, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Sand Hills State Forest". scfc.gov. South Carolina Forestry Commission. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ↑ "Angelina National Forest". fs.usda.gov. United States Forest Service. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ↑ "Sabine National Forest". fs.usda.gov. United States Forest Service. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ↑ "Big Woods now a state forest, wildlife area | The Tidewater News". www.tidewaternews.com. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Piney Grove Preserve | The Nature Conservancy in Virginia". www.nature.org. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Juras, Philip (1997). "The Presettlement Piedmont Savanna: A Model For Landscape Design and Management". Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- 1 2 Rostlund, Erhard (1960). "The Geographic Range of the Historic Bison in the Southeast". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. 50 (4): 395–407. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1960.tb00357.x. JSTOR 2561275.

- ↑ Parker, Douglas Seabrook (1998). Using Botanical Analysis to Shape a Longleaf Restoration Project (MS thesis). North Carolina State University. p. 83. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ↑ Pringle, Laurence P (1979). Natural fire. New York: William Morrow and Company. p. 35. ISBN 0-688-32210-7.