Edward Joshua Cooper (May 1798 – 23 April 1863)[1] was an Irish landowner, politician and astronomer from Markree Castle in County Sligo. He sat in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom from 1830 to 1841 and from 1857 to 1859, but is best known for his astronomy, and as the creator of Markree Observatory.

His observatory was home to the largest refracting (telescope with a lens) of the 1830s (an almost 14 inch astronomical grade Cauchoix of Paris lens, the largest in the World), and the asteroid 9 Metis was discovered there in the 1840s by his assistant. Several astronomical catalogs were also produced in the 19th century there.

Early life and family

Cooper was the oldest son of Edward Synge Cooper MP (1762–1830), and his wife Anne Verelst, daughter of Bengal Governor Harry Verelst.[2] He was educated at The Royal School in Armagh,[3] at Eton, and then at Christ Church, Oxford.[4]

His first marriage was to Sophia L'Estrange, daughter of Colonel Henry Peisley L'Estrange of Moystown, Cloghan, County Offaly. They had no children, but he had five daughters with his second wife Sarah Frances Wynne, daughter of Owen Wynne MP of Hazelwood House, Sligo.[4]

Astronomy

Cooper left Oxford after two years without taking a degree. He spent most of the next decade travelling abroad, pursuing an interest in astronomy which is believed to have been nurtured by his mother, and was developed as a schoolboy in Armagh on visits to the Armagh Observatory.[5] He travelled with portable instruments, which he used to calculate the latitudes and longitudes of the places visited and assess their potential for astronomical observation. He accumulated a mass of geographical data, which he never published.[3]

His early travels took him to the Mediterranean and Egypt, then eastward to Turkey and Persia. In 1824–5 he crossed Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, as far as the North Cape. He concluded that Munich and Nice were the best adapted spots in Europe for astronomical observation.[3]

When his father died in 1830, he succeeded him as manager of Markree Castle and estate on behalf of his father's deranged older brother Joshua Edward Cooper.[3] When Joshua Edward died childless in 1837,[6] he inherited Markree.[4]

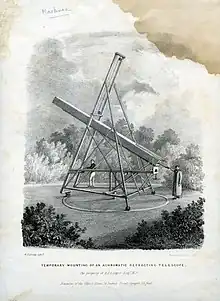

Once established as manager, he began creating facilities for astronomy, which became Markree Observatory. In 1831 he bought for £1200[7] the largest object-glass which existed at the time.[5] Made by the French optician Cauchoix, it had an aperture of 13⅓ inches (33.9 cm) across and a focal length of 25 feet (7.6 m).[5] The telescope initially mounted on a wooden stand, but the arrival of the great lens had caught the attention of Dr Thomas Romney Robinson, who had become director of the Armagh Observatory in 1823, and become a friend of Cooper's[5] At Robinson's suggestion, the telescope was removed its temporary alt-azimuth stand, and mounted equatorially by Thomas Grubb of Dublin,[5] with the innovation of a cast iron tube and stand,[3] instead of the wooden mountings previously used.[5] (This was the first major commission for Grubb, who was assiduously promoted by Robinson, and went on to become a noted producer of telescopes for observatories all around the world).[8] However, it was thought impractical to build a dome of the required size, so the instrument was set up outdoors, and remained uncovered.[3] Cooper used the telescope to sketch Halley's Comet in 1835 and to view the solar eclipse of 15 May 1836.[9]

The observatory was expanded with a five-foot transit by Troughton, and a meridian-circle three feet in diameter, fitted with a seven-inch telescope which had been ordered in 1839 on a visit to the works of Ertel in Bavaria. In 1842 he bought a comet-seeker, also made by Ertel. By 1851 Markree was described as "undoubtedly the most richly furnished of private observatories".[3]

Cooper's own diligent work in the observatory was joined in March 1842 by an assistant, Andrew Graham, who gave a fresh impulse to its activity. In 1842 to and 1843 the two men worked together to accurately record the positions of fifty stars within two degrees of the pole.[3] Graham began systematic observations of minor planets on the meridian.[5]

The latitude and longitude of Markree were calculated in 1841 by a joint exercise with Armagh.[3][5] In 1837, Robinson had obtained rockets from the Board of Ordnance at Woolwich, and a total of 76 rockets were fired from Slieve Gullion (a mountain in County Armagh) on five night between 14 May and 23 May.[10] The rockets were simultaneously observed from Armagh Observatory and Dunsink Observatory in County Dublin, and the data used to calculate latitude and longitude.[10] The same technique was used again in August 1841 to determine Markee's location. Rockets were fired from Culkagh Mountain, about 6 miles north-east of Lough Allen, and the precise moment of their extinction was observed at both Markree and Armagh. The results varied by only 0.03 seconds from the average of 15 chronometers lent by Dent of London.[11]

Similar principles were applied on 10–12 August 1847, to calculate the difference of longitude between Markree and Killiney, ninety-eight miles away in County Dublin. This time, shooting stars were simultaneous observed by Cooper in Killiney and Graham at Markree.[5][11]

On 25 April 1848, Graham used the Ertel comet seeker at Markree to discover a ninth minor planet.[5] It was named "9 Metis" at the suggestion of the late Dr. Robinson, because its detection had ensued from the adoption of a plan of work laid down by Cooper.[3] 9 Metis was the only asteroid ever discovered by observation from Ireland,[12] until the 2008 discovery of TM9.[13]

Meteorological registers were continuously kept at Markree during thirty years from 1833, many of the results being communicated to the Meteorological Society. In 1844–5 Cooper and Graham made an astronomical tour through France, Germany, and Italy. They brought the great refractor, which was mounted on a wooden stand with altitude and azimuth movements, was usd by Cooper to sketch the Orion nebula. On 7 February 1845 he used it to detect independently at Naples, a comet which had already been observed in the southern hemisphere.[3]

From the time that the possibility of further planetary discoveries had been recalled to the attention of astronomers by the finding of Astræa 8 Dec 1845, Cooper had it in view to extend the star-maps then in progress at Berlin, so as to include stars of the twelfth or thirteenth magnitude. A detailed acquaintance with ecliptical stars, however, was indispensable for the facilitation of planetary research—Cooper's primary object—and the Berlin maps covered only an equatorial zone of thirty degrees. He accordingly resolved upon the construction of a set of ecliptical star-charts of four times the linear dimensions of the 'Horæ' prepared at Berlin. Observations for the purpose were begun in August 1848, and continued until Graham's resignation in June 1860. The results were printed at government expense in four volumes with the title 'Catalogue of Stars near the Ecliptic observed at Markree' (Dublin, 1851–6). The approximate places were contained in them of 60,066 stars (epoch 1850) within three degrees of the ecliptic, only 8,965 of which were already known. A list of seventy-seven stars missing from recent catalogues, or lost in the course of the observations, formed an appendix of curious interest. The maps corresponding to this extensive catalogue presented by his daughters after Cooper's death to the university of Cambridge, have hitherto remained unpublished. Nor has a promised fifth volume of star places been forthcoming. For this notable service to astronomy, in which he took a large personal share, Cooper received in 1858 the Cunningham gold medal of the Royal Irish Academy. He had been a member of that body from 1832, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society 2 June 1853.[3]

Cooper had observed and sketched Halley's comet in 1835; Mauvais' comet of 1844 was observed and its orbit calculated by him during a visit to Schloss Weyerburg, near Innsbrück (Astr. Nach. xxii. 131,209). The elements and other data relative to 198 such bodies, gathered from scattered sources during several years, were finally arranged and published by him in a volume headed 'Cometic Orbits, with copious Notes and Addenda' (Dublin, 1852).[14] Although partially anticipated by Galle's list of 178 sets of elements appended to the 1847 edition of Olbers's 'Abhandlung,' the physical and historical information collected in the notes remained of permanent value, and constituted the work a most useful manual of reference. The preface contains statistics of the distribution in longitude of the perihelia and nodes of both planetary and cometary orbits, showing what seemed more than a chance aggregation in one semicircle. Communications on the same point were presented by him to the Royal Astronomical Society in 1853 (Monthly Notices, xiv. 68), to the Royal Society in 1855 (Proc. vii. 295), and to the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1858 (Report, ii. 27).[3]

On 22 October 1852 he discovered NGC 46, a star in the constellation Pisces that he incorrectly identified as a nebula.[15]

Politics

At the 1830 general election, Cooper was returned as one of the two members of parliament (MPs) for County Sligo. His family had held one of the two Sligo seats for most of the previous century; his father, who had held the seat until the dissolution, died during the 3 days of polling.[4]

The county's politics were dominated by the interests of its large Protestant landowners. The Wynne family of Hazelwood controlled Sligo Borough, while the county representation reflected the strength of the Coopers, the O'Haras of Annaghmore, and the Percevals of Temple House in County Sligo. At the dissolution, the second Sligo seat was held by Henry King, brother of Viscount Lorton. However, these two Protestant Tories were challenged by an independent interest which sought the return of "liberal and enlightened representatives".[16]

The candidate of the independents was Fitzstephen French of Frenchpark in Roscommon, brother of Arthur French MP. Unlike the sitting MPs, French supported Catholic emancipation, and proclaimed his adherence "not to the principles of Whig or Tory, but to the principles of Irishmen". As part of the compromise which had secured the enactment of the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, the Forty Shilling Freeholders had been disenfranchised. However, with the property qualification for voting quintupled to £10, the number of voters in County Sligo fell from over 5,000 to just over 600.[16] French's challenge was defeated; King was re-elected with 390 votes, and Cooper topped the poll with 465 votes to French's 116.[17]

In Parliament, Cooper opposed Earl Grey's reform bill in at its second reading in March 1831, but a few days later he presented a petition from Sligo borough which supported reform. In April he presented an anti-reform petition from County Sligo, and voted for the wrecking amendment which sank the bill and brought down the government. A few days before the crucial vote he had told the Commons that the bill would cause "the total annihilation of Protestantism, by the increased influence in elections which it gives to the Catholics".[4]

At the resulting general election in May 1831, Cooper condemned the failed reform bill as rushed, and again topped the poll,[17] When the revised Reform Bill came before the Commons, he voted against it at both the second and third readings.[4] He was returned unopposed in 1832 and 1835, and stood down in 1841, before returning in 1857 for one parliament.[4]

Religion

Cooper played a significant part in the editorial work of the third edition of the pseudohistorical anti-Catholic pamphlet The Two Babylons by Alexander Hislop.[18] The tract alleges that the Catholic Church is a veiled continuation of the pagan religion of Babylon, a product of a millennia-old conspiracy.[19] All of the book's major claims have been thoroughly refuted by modern scholarship.[20]

The book's preface extensively praises an anonymous collaborator. Cooper wanted to remain anonymous when the book went to press, but by the seventh edition a footnote identified him as mystery editor. Hislop praises Cooper's meticulous attention to detail, his extensive library and his views on Christianity, and thanks him for "the incalculable value of the service which the extraordinary labours of my kind and disinterested friend have rendered to the cause of universal Protestantism."[18]

Death

Cooper died aged 64 on 28 April 1863.[7] He was buried in a vault at the Church of Ireland church in Ballisodare,[21] alongside his second wife, Sarah, who had died shortly before him.[7] According to William Doberck, who began work at the observatory a decade later, he had been a kind and improving landlord.[22] The Cork Examiner described him as "celebrated for his scientific attainments, moral worth and estimable character".[23] The Obituary Notice in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, 1864 said he "was a kind and good landlord, making great exertions to educate and improve his numerous tenantry. His personal qualities were of a high order. Blameless and fascinating in private life, he was a sincere Christian, no mean poet, an accomplished linguist, an exquisite musician, and possessed a wide and varied range of general information."[24]

His estates were inherited by his nephew Edward Henry Cooper, who initially neglected the observatory, before appointing a series of directors.[12] The observatory was restored under Doberck's supervision from 1874, but was used mainly for meteorological investigation. When Edward Henry Cooper died in 1902, the observatory was closed and its great lens sent to the Hong Kong Observatory. The observatory's library was converted into a garage, and its books dumped into a hole in the floor of a neighbouring room, which was exposed to rain through an uncovered slit in the roof.[7][12]

|

References

- ↑ Leigh Rayment's Historical List of MPs – Constituencies beginning with "S" (part 3)

- ↑ Aspinall, Arthur (1986). R. Thorne (ed.). "COOPER, Edward Synge (1762–1830), of Markree Castle, co. Sligo and Boden Park, co. Westmeath". The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1790–1820. Boydell and Brewer. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Clerke, Agnes Mary (1887). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 12. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Salmon, Philip (2009). D.R. Fisher (ed.). "COOPER, Edward Joshua (1798–1863), of Markree Castle, co. Sligo and Boden Park, co. Westmeath". The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1820–1832. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Elliott, Ian (2007). Hockey, Thomas; Williams, Thomas; Trimble, Virginia (eds.). Cooper, Joshua Edward. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 250–1. ISBN 978-0387304007.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Aspinall, Arthur (1986). R. Thorne (ed.). "COOPER, Joshua Edward (?1761–1837), of Markree Castle, co. Sligo". The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1790–1820. Boydell and Brewer. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Steinicke, Wolfgang (2010). Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer's New General Catalogue. Cambridge University Press. pp. 137, 252. ISBN 9780521192675.

- ↑ Glass, Ian S. (2007). Hockey, Thomas; Williams, Thomas; Trimble, Virginia (eds.). Grubb, Thomas. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 447–8. ISBN 978-0387304007.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ History of the Cauchoix objective

- 1 2 Robinson, Thomas Romney (1837). Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 1. Royal Irish Academy. pp. 338–41.

- 1 2 Cooper, Edward Henry (1837). On the Determination of Differences of Longitude, by Means of Shooting Stars. Vol. 4. Royal Irish Academy. pp. 6–14.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 Whyte, Nicholas (1999). Science, Colonialism and Ireland. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press. pp. 30–32. ISBN 978-1859181850. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ Cooper, Edward J. (1851). "Cometic Orbits". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Royal Astronomical Society. 12 (2): 25–26. Bibcode:1852MNRAS..13...25C. doi:10.1093/mnras/12.2.34.

- ↑ "New General Catalogue objects: NGC 1 - 49". Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- 1 2 D.R. Fisher, ed. (2009). "Co. Sligo". The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1820–1832. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- 1 2 Walker, Brian M., ed. (1978). Parliamentary Election Results in Ireland 1801–1922. A New History of Ireland. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. pp. 238, 312. ISBN 0901714127. ISSN 0332-0286.

- 1 2 Hislop, Alexander (1871) [1853]. The Two Babylons (7th ed.). Cosimo. p. xii. ISBN 9781602061392. Retrieved 25 June 2017 – via Internet archive.

- ↑ Grabbe, Lester L. Can a 'History of Israel' Be Written? p. 28, 1997, Continuum International Publishing Group

- ↑ Mcllhenny, Albert M. (2011). This Is the Sun?: Zeitgeist and Religion (Volume I: Comparative Religion). Lulu.com. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-105-33967-7. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ↑ "Funeral of the late Edwd J. Cooper, Esq of Markree Castle". Dublin Evening Mail. via British Newspaper Archive. 4 May 1863. p. 3. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ Clerke, A. M.; Wayman, P. A. "Cooper, Edward Joshua (1798–1863), landowner and astronomer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6216. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "National Obituary for the Year 1863". Cork Examiner. via British Newspaper Archive. 1 January 1864. p. 4. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ Hislop, Alexander (1871). The Two Babylons (7 ed.). London: S. W. Partridge & Co. pp. xii, 360. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Burke, Bernard (1871). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. 1 (5th ed.). London: Harrison. p. 277.