.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms of the Principality of Romania. | |

| Date | February 23 - April 20, 1866 |

|---|---|

| Duration | February 22, 1866 Deposition of Alexandre Jean Cuza.

February 23, 1866 Election of Prince Philippe of Belgium, Count of Flanders, followed by his rejection. March 10, 1866 Opening in Paris of the conference on the Danube principalities. April 20, 1866 Election of Prince Charles of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen by the Romanian parliament. May 22, 1866 Prince Carol I of Romania enters Bucharest. |

| Location | Principality of Romania Europe Ottoman Empire |

| Outcome | Election of Charles of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as sovereign prince of the Romanian principalities. |

The election to the Romanian throne in 1866 followed the deposition of Prince Alexandre Ioan Cuza, with the aim of giving the united principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia a new ruler.

Cuza's deposition, despite his major reforms which had initiated the modernization of the Romanian principalities, had been engineered by an alliance of inherently opposed political and social forces: the "Monstrous Coalition", backed by Russia, wanted the sovereign to leave, accusing him of Caesarist tendencies. His succession proved a delicate matter.

The issue went beyond the Danube principalities, since it involved the political balance and economic interests of the main European powers, as well as the Ottoman Empire, the principalities' sovereign. A provisional Romanian governmental lieutenancy was set up to appoint a new candidate. The 1858 Paris intergovernmental conference had called for the election of an indigenous sovereign, but the Romanian provisional government opted straightaway for a prince from a European dynasty.

The first candidate, Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders and brother of King Leopold II, elected before he was even informed, almost directly declined the offer made on February 23, 1866, as he had no wish to lead an "Eastern Belgium" that would be a vassal of the Ottoman Empire. Meeting in Paris on March 10, the chancelleries of the European guarantor powers were divided over the Danube principalities, weakening the international political situation whose prospects were already clouded by the imminence of the Austro-Prussian War.

Rejecting Nicolas de Leuchtenberg's overly Russophile candidacy, the powers suggested several other candidates, which were quickly rejected. Ahead of the dithering chancelleries, the Romanian government chose its own candidate, after secret negotiations with France and Germany. Prince Charles of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen was elected by the Romanian parliament in a referendum on April 20, 1866.

Presenting the Ottoman Empire with a fait accompli, the Prussian prince accepted and officially entered Bucharest on May 22, 1866, where he became "Domnitor" (sovereign prince). Under the name of Carol I, he established, within the framework of the new Romanian constitution, the beginnings of the Kingdom of Romania, which became fully independent in 1878, and founded the dynasty of sovereigns who reigned over Romania until 1947.

Background

Unification of the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia

After almost four centuries of exclusive vassalage to the Ottoman Empire, the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia were placed under the protection of Russia by the Treaty of Andrianople of September 14, 1829, while remaining under the domination of the Ottoman Empire. The Romanian revolution of 1848 (essentially intellectual in Moldavia, but more martial in Wallachia) was peacefully subdued in Moldavia by Austria, but severely repressed by Ottoman troops, backed up by Russian troops, in Wallachia.[2]

Following the Crimean War, the 1856 Treaty of Paris confirmed the autonomy of the two principalities, ceding back to Moldavia the three southern Russian departments of Bessarabia, but restricting this autonomy by keeping it under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire and under the guarantee of the signatory powers.[3] The principalities retained independent national administration, as well as freedom of worship, legislation, trade and navigation.[4]

After three months of meetings between the guarantor powers and the Ottoman Empire, a convention on the organization of the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia was signed at the Paris Conference on August 19, 1858. The convention was ratified on October 7 by France, Austria, Great Britain, Prussia, Russia, Sardinia and the Ottoman Empire. It stipulated that the Danubian principalities would henceforth be known as the "United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia", and would remain under the sovereignty of the Sultan, while administering themselves freely without Ottoman interference. In each of the principalities, public powers were entrusted to a hospodar[note 1][5] and an elective Assembly.[6]

Three months later, Colonel Alexandre Ioan Cuza, a Francophile from the noble boyar class but a modest landowner, was elected Hospodar of Moldavia on January 17, 1859. This choice astonished the chancelleries, who were convinced that he would fall to Mihail Sturdza, formerly reigning prince of Moldavia, an enlightened despot who had enriched himself greatly personally. The vote in Cuza's favor was reiterated when he was unanimously appointed hospodar of Wallachia on the following February 5.[7]

This double election of the same hospodar demonstrated the will of the two principalities to be united from now on, driven by the mission to destroy every last vestige of the absolutism of the past.[8] The Paris conference of April 1859, held to settle the question of Cuza's double election, validated the fait accompli, but maintained the administrative separation of the two principalities.[9] A further conference was held in Paris in September 1859, at which time, after taking note of Sultan Abdülaziz's authorization, a protocol validated the acceptance of Cuza's double investiture. The Ottoman Empire, through the firman (royal decree) of December 4, 1861, enshrined the legislative union of the two principalities for as long as Cuza was alive, thus paving the way for the legislative and administrative union of the two principalities. However, the Sultan refused to allow them to be called "Romania". The Moldavian and Wallachian Assemblies merged on February 5, 1862.[10]

Reign and reforms of Alexandre Ioan Cuza

Although Prince Alexandre lacked personal ascendancy, he did have the merit of choosing progressive ministers, eminent figures in Romania's cultural Renaissance, such as Vasile Alecsandri, a man of letters, Carol Davila, head of the army medical service[11] and Mihail Kogălniceanu, historian and jurist. Cuza was thus the political representative of a Romania that was now united and determined to break away from the frameworks inherited from the Middle Ages and enter modernity. The image of France as a model was very present in Romania. Ties between French diplomatic representatives in the Romanian principalities and the new power in Bucharest were close. Victor Place, the French consul in Iași, was one of Alexandre Cuza's main advisors.[12]

Assisted by his Prime Minister Mihail Kogălniceanu, an intellectual leader active during the 1848 revolution, Alexandre Cuza undertook a series of reforms that contributed significantly, in a short space of time, to the modernization of Romanian society and state structures.[13]

Status of farmers and their land

For this largely unindustrialized nation, Romania's main source of wealth was agriculture.[14] In December 1863, Alexander Cuza decided to secularize the immense ecclesiastical estates belonging to the 172 monasteries, and to confiscate "mainmorte" property (belonging to congregations and therefore exempt from the inheritance fees associated with transfers by death). These measures affected almost a quarter of the useful agricultural area belonging to Orthodox monks under the monastic republic of Mount Athos or the Patriarch of Constantinople, to whom they sent a substantial part of their enormous land income.[15] A few months later, the agrarian reform of August 1864 freed peasants from the last feudal drudgery and granted them freedom of movement. In a country with 4,425,000 inhabitants and 684,000 farming families,[14] some 512,000 peasant families became owners of the land they farmed.[note 2][16]

Emancipation of minorities

The secularization of monastery property and agrarian reform led to the complete emancipation of the Roma, who were no longer tied to a boyar family or monastery.[17] As for the Jews (whose numbers had increased considerably since 1860, following mass emigration from Poland and Galicia to Moldavia), the granting of communal rights to indigenous Jews under certain conditions by the law of March 31, 1864, and the naturalization of those who met certain requirements laid down by the new civil code, improved their status and fostered recognition of their community. However, no Jews were actually naturalized in the two months between the implementation of the civil code and the deposition of Alexandre Cuza.[18]

Political and judicial reforms

Following the referendum of June 4 and 7, 1864, a Senate was created on July 3 in the Romanian provinces, which were then represented by a bicameral system.[19] Its first president was the Metropolitan Primate of Bucharest, Nifon Rusailă.[20] That same year, Alexandre Cuza implemented and promulgated a new civil code in December 1865, most of which was translated from the 1804 French civil code and also inspired by Prussian laws.[21] French legal influence was grafted onto the Franco-Romanian socio-cultural bond. The Civil Code influenced Romanian society in its entirety, preparing minds to accept new French ideas embodied in Romanian law. At first glance, however, the Code's reception by Romania's rural majority proved difficult, due to the modernity of its provisions and the language used.[22] At the same time as the new Civil Code, a Commercial Code was published, also inspired by French law.[23] In October 1864, the new penal code abolished the death penalty and corporal punishment, considerably changing the Romanian legal landscape.[24]

Education and healthcare

Cuza promoted the introduction of free, compulsory public primary education for both sexes[15] in the majority of rural communes[14] and the organization of secondary education in seven colleges and lyceums across the country. He opened the National University of Art in Bucharest, as well as military, medical and pharmacy schools.[14] He also created two new public universities: the Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iași in 1860 (formerly the Mihăileană Academy, with three faculties: law, philosophy and theology) and the University of Bucharest in 1864, which opened faculties of law, science and literature.[25]

While there were already 35 hospitals (including a hospital for the insane and two institutes for abandoned children) in the country, either publicly funded (central hospitals and district hospitals) or privately initiate,[14] a new hospital structure, established in Colentina (a district of Bucharest), was inaugurated in February 1864 by Alexandre Cuza to celebrate his five-year reign. The hospital offered patients 100 medical and surgical beds, as well as a free consultation service.[26]

Development of communications and the army

Alexander Cuza initiated the construction of the country's first railroad line, thanks to an agreement signed in September 1865 with the British company Barkley-Staniforth. The 67-km line ran from Bucharest to the port city of Giurgiu, transporting agricultural produce to the Danube and then to the Black Sea, and supplying the Romanian capital with imported goods.[27] The line was only inaugurated in October 1869 by Carol I.[28] Despite limited financial resources, Cuza also undertook public works, such as the development of the road network.[29] At the same time, Cuza promoted the development of a modernized Romanian army, with operational links to France. The Romanian army now numbered 45,000 men and 12,000 horses.[14] Napoleon III, in the name of defending the principle of nationality, deployed a French military mission within the Romanian army from 1860 to 1869. Cuza was not satisfied with simply ordering cannons from France; he wanted closer cooperation.[30] At Cuza's request, his foreign minister Vasile Alecsandri travelled to Paris to request the arrival of French instructors in all disciplines of military art. Napoleon III agreed, and also promised to send specialists capable of setting up the foundries and factories essential to the army. Despite administrative difficulties, Franco-Romanian military cooperation proved advantageous to the development of the Romanian army and accelerated the process of unifying the armies of the two principalities.[31]

The impact of the reforms

These fundamental reforms, designed to "regenerate the Danube principalities" and imposed by Cuza to enable Romania to effectively enter the 19th century, therefore concerned all social classes. However, before he succeeded in imposing his reforms, Cuza ran up against the opposition of many deputies. On May 14, 1864,[32] he achieved the pinnacle of his power through what some would describe as a veritable coup d'état: he dismissed the deputies of the Legislative Assembly by military force, because they refused to deliberate on the bill considerably broadening the electoral base. In addition to dissolving the Chamber, he decreed an additional article "motu proprio" to the electoral law, inviting Romanian citizens to vote "yes" or "no" on measures emanating from the sole authority of the hospodar.[note 3][33] The referendum gave him 682,621 yes votes to 1,307 no votes.[34] In June 1864, on the strength of this popular support, Cuza went to Constantinople to ask the Sultan, in agreement with the guarantor powers, to validate the new institutions he had set up: from then on, the united principalities could amend the laws governing their internal administration. While Cuza's agrarian reform won him solid support among the peasantry, who saw him as their emancipator,[35] he exasperated the opposition of the conservative boyars, who saw the agrarian law as spoliation and rallied a fraction of the "centrists" to their cause. In the summer of 1864, at the height of his power, his Caesar-tinged regime alienated several classes of the population.[36]

The upper classes questioned the principle of union of the two principalities in October 1864. On August 15, 1865, in Cuza's absence, public disturbances broke out in Bucharest. The scuffles, encouraged by domestic opposition parties and suppressed by the army, were deemed sufficiently serious (20 people were killed) to warrant an official letter from Mehmed Fuad Pasha, Ottoman Grand Vizier, requesting explanations.[37] For their part, the clergy and conservative bourgeoisie also opposed the reforms. On the other hand, the more radicals considered the reforms insufficient, and criticized Cuza for his propensity to accommodate the ruling classes, going so far as to compare his reign to a liberticidal dictatorship that starved the population after ruining landowners and eliminating many administrative jobs.[25]

Prince Alexander thus failed in his efforts to create an alliance between prosperous peasants and a strong, liberal prince, who would rule like a benevolent despot in the manner of Napoleon III.[38] A financial depression caused by wheat speculation, a scandal fomented by the clergy concerning his mistress Elena Maria Catargiu-Obrenović,[39] and popular discontent due to the inadequacy, but also incomprehension, of his reforms led to an unnatural connivance between conservatives and radical liberals, which Romanian humanists called the "Monstrous Coalition". This alliance was determined to topple Cuza and replace him with a foreign prince from a European dynasty. Cuza's opponents saw their ranks swell; already in the spring of 1864, they had sent several delegations to Paris, Turin, Vienna and London to prepare the deposition of their sovereign. The regime's days were numbered, and Cuza considered abdicating at the end of 1865.[40]

The spectre of Panslavism

Russia, which until then had officially supported Cuza, changed its attitude when it saw that the Prince's regeneration program was consolidating its position. Unable to deploy its troops in Bucharest and Iași, it used other means to bring down the government in order to split the country and impose a regime of its own choosing. It employed subversion and propaganda, harshly criticizing Cuza's policies, and launched a systematic campaign to denigrate the Romanian government through its diplomats and newspapers (such as the Journal de Saint-Pétersbourg, Russky Invalid and Moskovskiye Vedomosti). While encouraging troublemakers in Romania, Russia denounced them in order to justify military repression.[41] However, Europe feared that intervening in Romanian affairs would revive the Eastern Question and revive the scarecrow of Panslavism that had led to the Crimean War.[42] Cuza was not fooled and wrote: "As long as Russia thought that the union of principalities could become a cause of weakening for Turkey, it was affected to show itself favorable to this combination [...], but when it saw that by developing, Romania could become an obstacle to the invasion of Panslavism, it attacked, on the contrary, everything that hindered our development".[41] In January 1866, Russian newspapers floated the idea of secession from Moldavia, where in the capital, Iași, commerce and the main institutions were adversely affected by their transfer to Bucharest, which had become the sole capital of the two principalities. Real estate values were substantially reduced, provoking discontent among Moldavian boyars and merchants. On the other hand, Moldavian peasants were grateful to Cuza, who had extricated them from their servile condition. With the exception of Iași, the separatist idea met with no success in the other Județe. For its part, Russia tried to frighten the Romanian authorities by positioning troops along the Moldovan border.[41]

The deposition of Alexandre Cuza

At 4 a.m. on February 22, 1866, a band of conspirators, aided and abetted by soldiers, entered the royal palace in Bucharest, and ordered the prince to sign his act of abdication. He complied without resistance. For his own safety, he was held for a few hours in a house in the city, before being escorted in the evening to the Cotroceni Palace, where he spent the night before being escorted back to the border the following day, from where he travelled to Vienna.[43]

Historian Traian Sandu considers Cuza's downfall to be essentially the result of collusion between political extremes and possible connections with conservative powers.[44] For his part, historian Paul Henry[note 4][13] draws up a positive assessment of the reign, despite its brevity: "Few governments have been able to claim to have achieved such profound, important and decisive reforms in five years. All this was not without raising animosities, jealousies of the pretenders to the throne whose ambitions he hindered, resentments of the dispossessed boyars, anger of the powers whose selfish calculations or unpredictability he thwarted, worries of the sovereign power faced with the awakening of a Christian nationality, resentment of the parties whose utopias he rejected. In short, Cuza had defied all odds to accomplish what he considered to be the destiny of his country".[13]

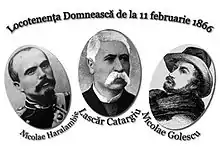

- Leaders of the "Monstrous Coalition" responsible for ousting Alexandre Cuza

Constantin A. Rosetti (radical)

Constantin A. Rosetti (radical) Lascăr Catargiu (conservative)

Lascăr Catargiu (conservative) Ion Ghica (moderate liberal)

Ion Ghica (moderate liberal)

First election (February 1866)

Provisional government

The deposition of Prince Cuza called into question the achievements of the Romanian principalities: a common prince, merged administrations and divans;[note 5][45] while the question of international recognition of Romanian unity remained unresolved.

After the departure of Alexander Cuza, the leaders of the "Monstrous Coalition" formed a provisional government headed by Ion Ghica, also Minister of Foreign Affairs, and comprising several other members of the Romanian nobility ousted in favor of Cuza in 1859: Dimitrie Ghika (Interior) and Jean Alexandre Cantacuzène (Justice), to whom should be added Constantin Alexandru Rosetti (Cults and Public Instruction), Petre Mavrogheni (Finance), Dimitrie Sturdza (Public Works) and Dimitrie Lecca (War). The provisional government's most urgent task was to elect a new sovereign, in line with the adoption of a new constitution.[46] Article 13 of the 1858 Paris Conference stipulated that anyone aged thirty-five and the son of a Moldavian or Wallachian-born father could be elected to the Hospodorate, provided they had held public office for ten years or were a member of the Assemblies.[47] In Moldavia, a factionalist ideological movement led by Nicolae Ionescu had been advocating anti-monarchism even before Cuza came to power. Ionescu had studied law in Paris before taking part in the 1848 revolutions in Paris and then Romania, and was opposed in principle to the establishment of a foreign prince at the head of the country.[48] However, in the eyes of the provisional government, the choice of a foreign prince appeared to be the best option, but by entrusting the fate of their country to the protecting powers, the Romanian patriots were implicitly jeopardizing the fragile gains of the previous decade.[49]

Appointment of Philippe of Belgium

In the early hours of February 23, 1866, Bucharest was militarily occupied by the entire army. A proclamation posted and distributed to the population announced the abdication of Prince Cuza and the appointment of a regency (princely lieutenancy) in the form of a triumvirate made up of Nicolae Golescu, Lascăr Catargiu and colonel Nicolae Haralambie. The latter, commander of the I artillery regiment, was personally involved in the conspiracy that deposed Prince Cuza. At one o'clock, the chambers met to receive the lieutenancy and the new ministry. A left-wing deputy, Mihail Paplica, removed and tore the veil covering the throne, above which was engraved the figure of Prince Cuza. He tore off the emblem and shattered it to the cheers of the assembly.[50] At two o'clock, the President of the council, Ion Ghika, took to the rostrum and proposed the name of Philippe of Belgium, Count of Flanders, to the senators and deputies, arousing unanimous enthusiasm. Metropolitan Primate Nifon Rusailă supports the election, and War Minister Dimitrie Lecca confirms the army's loyalty to the Belgian prince.[51] The leader of the opposition, General Christian Tell, also welcomed the choice, which had just "saved the country from ruin", and asked that a record be drawn up recognizing the election.[52]

The United Romanian Principalities had thus unanimously elected the second son of the late Belgian King Leopold I as their Domnitor, under the name of Philippe I. They hoped he would import his country's institutions and, thanks to a new constitution inspired by the Belgian model, create a kind of "Eastern Belgium" in the Lower Danube.[53] As soon as the news of this election became known, the Journal de Saint-Pétersbourg, the unofficial organ of the Russian Foreign Ministry, published an editorial pretending to regret Cuza's fall and advising the Count of Flanders to await the decision of the diplomatic conference scheduled to meet on the future of the Danube principalities. Unofficially, Russia gave its agents a threefold mission: to ensure that the provisional government did not exceed the remit of a local police force, to exert no pressure on those who wished to return to the old order of things, and to provide underhand encouragement to the separatist party. As for the Russian newspapers, they claimed that the union had not benefited the principalities and had met with no sympathy among the Moldovan population. In view of these reasons, the Russian press declared itself in favor of separate elections, so that the people's wishes could be truly expressed. Great Britain, preoccupied with the forthcoming conflict between Austria, Prussia and Italy, regarded the question of the Romanian principalities as incidental and supported the status quo. Austria, too preoccupied by its anticipated war with Prussia, was unable to make its point and needed the assurance of French neutrality in its dispute with its future adversaries.[41]

As early as March 1856, the Belgian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Charles Vilain XIIII, was thinking of opening consulates in the Danube principalities. He requested the assistance of Eduard Blondeel Van Cuelebroeck, then diplomat in Constantinople, to ensure trade relations with the newly independent Romanian principalities. Blondeel was suspected of wanting to unite Moldavia and Wallachia, with the help of Jacques Poumay, Belgian consul in Bucharest, and of supporting the idea of electing Philippe de Belgique, who received the information on March 23, 1857. The latter gave no response to this proposal. The information having been leaked, Blondeel had to leave his post in Constantinople.[51]

On February 24, 1866, Philippe, who had never asked for such a position, curtly refused. The next day, Charles Rogier, the Belgian head of cabinet, also in charge of foreign affairs, informed Jacques Poumay, the Belgian consul in Bucharest, of the news of the Count of Flanders' probable refusal to accept the Romanian hospodorate,[51] and diplomatically added, to explain his absence, that the Count of Flanders had long planned to spend a vacation in Rome.[54] On his way to Rome, Philippe stopped off in Paris and informed Napoleon III of his decision. The latter implied that he had made the right choice.[55] On February 27, Rogier received in Brussels the Romanian delegation that had come to bring the news of the election. Two days later, the delegation learned that the new King of the Belgians, Leopold II, had refused to allow his brother to settle in Romania, pointing out that his brother was not ambitious.[51] Even if Philippe had been inclined to accept the Romanian offer, the Belgian king could not have envisaged a grandson of King Louis-Philippe occupying a foreign throne without offending Napoleon III, Belgium's powerful neighbor.[54] The offer of February 1866 can be seen as the final effect of the prestige enjoyed in Europe by his father, Leopold "the Nestor of sovereigns", who had died two months earlier.[56] It was only on his return from Italy on March 30, 1866, that the Count of Flanders formally announced his withdrawal from the Belgian government and pledged his loyalty to the future sovereign. This refusal was officially communicated to London and Paris.[57] The decision not to play a leading role can be explained by the prince's personality, who cultivated a taste for an existence relatively free of constraints, and also by the deafness from which he had suffered since his youth. Three years earlier, he had already ruled out any claim to the throne of Greece, citing the instability of the situation.[58]

As MP Alphonse Vandenpeereboom metaphorically put it, "this Romanian throne was refused by telegram with as much ceremony as if it was a cotton ball". As for Jean-Baptiste Nothomb, a friend of the Prince, he saw Philippe's election as a flattering tribute to his Belgian status, but felt that the Romanian throne would only be acceptable if offered by all six powers, otherwise it would just be a presidential chair.[59]

Waiting for a prince

Mediation by guarantor powers

After the withdrawal of Philippe of Belgium, the Romanian succession remained open to the diplomatic community, which was preparing to meet in Paris in March 1866. Since the beginning of his reign, Napoleon III had officially acted as protector of Romanian national interests, seeking to create a "bridgehead" of his own influence between the Austrians, Russians and Turks, acting as arbiter and supporter of the nascent Romanian state.[60] However, the reality was more complex, as the French emperor's policy evolved during the second decade of his reign, interfering with the German question.[61]

Economic consequences and military threat

From a European economic point of view, the continuing uncertainty in Romania led to a fall in London stock market prices, as Great Britain had given substantial material support to the principalities by committing capital for the creation of roads and bridges, and access to cheap waterways for the trade.[62] From a military point of view, tension increased around the Romanian provinces: the Sultan asked the powers that had signed the Treaty of Paris for authorization to intervene in the Danube principalities, while six Cossack regiments reinforced the Russian observation army stationed on the Moldavian border. Within the principalities themselves, troop movements were reported: reinforcements were sent from Bucharest to Iași, and a military cordon was established on the right bank of the Prut.[63]

A divisive candidacy

At the beginning of March 1866, there was talk of a new foreign candidate, namely Duke Nicholas of Leuchtenberg, nephew of Tsar Alexander II of Russia and unsuccessful candidate for the Greek throne in the royal election of 1862–1863, whose accession to the Romanian throne would resolve the Eastern Question in Russia's favor. This choice of a foreign prince, with close ties to the Romanovs, was also at odds with the Paris Conference of 1858.[63] Too closely related to the Tsar, the Duke of Leuchtenberg would inevitably appear as a "Russian governor" in the eyes of Romanian politicians and the guarantor powers. Moreover, the Russian Emperor stated that he would not accept a member of his family becoming a vassal of the Sultan.[64] In Great Britain, Lord William Gladstone announced to the House of Commons on March 7 that his country, the Sublime Porte and the Protecting Powers would be meeting in conference to discuss the Romanian situation; but he already warned his partners that the clauses of the 1856 Treaty of Paris must be respected.[65]

The division of the guarantor powers

The conference of ambassadors appointed to settle the principalities issue opened in Paris on March 10, and met five times until April 5 under the chairmanship of Édouard Drouyn de Lhuys, the French Foreign Minister, as he represented the host country. The conference begins by examining the question of navigation on the Danube. From the outset, however, discussions were overshadowed by the Prussian question, and also by the situation in Mexico, where Napoleon III was gradually withdrawing his troops from the empire he had founded.[66] In a letter from Drouyn dated March 16, France officially maintained its position in favor of maintaining the union of the Danube principalities under the authority of a foreign prince.[41]

The obstinacy of Russia (represented in Paris by Baron Andreas von Budberg, who received instructions from Foreign Minister Alexander Gortchakov) in insisting on the separation of the principalities irritated Great Britain, which considered that the Romanian provisional government would eventually impose its views thanks to the support of France, Prussia and Italy. During these weeks of meetings, the names of new candidates appeared in the press. In France, the newspapers mentioned Senator Lucien Murat as a potential candidate,[67] then other princes were approached: Ferdinand IV, the deposed Grand Duke of Tuscany, Amédée, Duke of Aosta, Augustus of Sweden, and even Alexander of Hesse, the Tsarina's brother.[68]

The inaction and indecision of the conference encouraged the Romanian provisional government, whose view that the Chambers, elected under Cuza's regime, could no longer legitimately represent the true ideas of the country, led it to dissolve them on March 30 to have a free hand.[43] Notified on April 5, the conference took no action against this new act of authority. The Anglo-Austrian proposal on April 9 to suspend ambassadorial meetings in Paris met with no opposition from the other participating powers. However, it was only on June 25, after receiving a note from Gortchakov inviting Great Britain to join Russia in maintaining peace in the Balkans, that Budberg proposed to Drouyn de Lhuys the official closure of the conference, which then ceased to meet.[41]

An unexpected choice

In its race against Iași's Russophile faction, the Romanian government took its adversary by storm and, instead of submissively waiting for a sovereign to be appointed, chose one for itself.[69] Ion Brătianu, one of the liberal leaders who had brought about Cuza's downfall, established secret contacts in Paris with Napoleon III, which led to the candidacy of Charles de Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, second son of Prince Charles-Antoine, formerly Minister-President of Prussia, still very influential in Germany and whose family was partly of French descent.[note 6][70] Ion Brătianu visits the Hohenzollerns at Jägerhof Castle in Düsseldorf on March 30.[71] Charles de Hohenzollern was not only an accomplished military man who had taken part in the decisive Duchy War victory at Dybbøl, but also a former student of Bonn University, where he had studied French history and literature.[72] He received Brătianu in audience on March 31. The potential candidate hesitates, as accepting means submitting to the Sultan's suzerainty and, possibly, embracing the Orthodox religion. Moreover, he could not commit himself without the consent of Prussian King William I, head of the Hohenzollern family. Without delay, the father of the potential candidate sent a memorandum to the King of Prussia. A few days later, Charles visited the court in Berlin. The King of Prussia did not raise the Romanian question, but his son the Kronprinz did, expressing regret that the proposal had come from France, while his nephew Prince Frederick-Charles of Prussia, a conservative officer, advised him against accepting.[73]

Second election (april 1866)

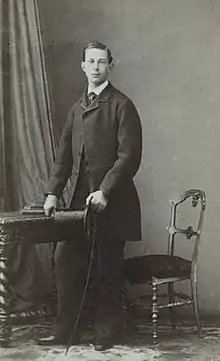

Election of Charles of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen

On April 13, 1866, in Bucharest, members of the princely lieutenancy and the ministry signed proclamations proposing that Charles of Hohenzollern be named Prince of Romania under the name of Carol I, before the candidate had accepted. The following day, a plebiscite was held, the results of which were known on April 20: 685,969 votes in favor, 224 against and 124,837 abstentions.[74] On the same day in Bucharest,[43] the votes of the Assembly (109 deputies supported the plebiscite results and voted in favor, against 6 abstentions) validated the results of the plebiscite and also endorsed the government's choice.[75] Informed of this electoral success, and of the King of Prussia's positive response, received on April 16, Otto von Bismarck (then Prussian Foreign Minister) suggested that Prince Charles, now determined to try his hand at adventure, should request leave from his dragoon regiment and travel directly to the Danube principalities, to inaugurate his reign. The policy of a coup de force combined with a façade of legalism thus prevailed.[76]

The coup d'état of Iași

While in Bucharest, the Hohenzollern candidacy was widely supported, the same could not be said of Iași, where the separatist Russophile faction was preparing a putsch and announced, in early April, the candidacy of judge Nicolae Rosetti-Roznovanu, from an ambitious family of great boyars, to head a Moldavia that would become independent.[note 7] The provisional government in Bucharest sent Nicolae Golescu, a member of the princely regency, to Iași to calm tempers and ensure that the government's instructions would be followed. Rosetti-Roznovanu replied that he could not accept the election of a foreign prince and declared himself in favor of Moldavian autonomy. His proposal was immediately acclaimed by the audience. A 16-member secessionist committee was immediately formed to oversee the Moldavian Electoral Assembly elections, which he planned to hold on April 21 and 29 to pronounce his separation from Wallachia.[77]

On April 15, 1866, following the morning church service in Iași's metropolitan cathedral, Nicolae Rosetti-Roznovanu and his followers, supported by several boyars, members of his family and Calinic Miclescu, the metropolitan of Iași, headed for the princely palace to proclaim Moldavian independence and oppose the election of "the infidel Carol the Catholic".[78] According to Le Debatte de Vienne, the Russian postmaster harangued the multitude.[79] The separatists (numbering around 500, including 200 Russian subjects), armed with stones and sticks, were pursued by lancers and took refuge in the Roznovanu palace, where they were besieged. There were 12 dead and 16 wounded in the ranks of the insurgents as a result of repression by the Moldavian armed forces, who fired after two soldiers had fallen.[80][81] After more than three hours of rioting, Rosetti-Roznovanu, Metropolitan Miclescu (who sounded the tocsin during the scuffles and was wounded)[82] and other conspirators, such as Constantin D. Moruzi, a Moldavian boyar and dregător (chancellor) of Russian origin,[83] were arrested and taken before the Minister of War, who imprisoned them. The insurrection, provoked by the Moldavian separatist movement, was an isolated seditious demonstration that was therefore effectively crushed,[84] highlighting the momentary weakness of the Russian Empire.[41]

The announcement in Düsseldorf

On April 25, 1866, Ion Brătianu, who had been actively involved in the election of Charles de Hohenzollern, left Bucharest for the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen family in Düsseldorf, where he officially announced to the prince the official results of the plebiscite of April 20, 1866 that had conferred sovereign authority on him, results confirmed by the unanimous vote of the Romanian deputies. Brătianu also provided extensive written and photographic documentation on the principalities the young man was about to rule, which he did not yet know.[76] On May 2, the Paris Conference for the Affairs of the Danube Principalities ordered a new election to be organized by the Romanian Chamber, but the latter almost unanimously reiterated the choice of the Prince of Hohenzollern expressed in the plebiscite of April 20. A few days later, the provisional government of the Moldo-Valcan principalities granted him Romanian naturalization.[85]

Journey to Romania

The adventure began with a clandestine journey. Because of the conflict between his country and Austria, Charles de Hohenzollern traveled to Romania disguised as a merchant. On May 11, 1866, he left his home in Düsseldorf and took a long detour by rail through Switzerland, stopping in St. Gallen to obtain a passport in the name of 27-year-old merchant Karl Hettingen. From there, he crossed Bavaria without stopping and reached Austria. On May 16, after wearing glasses to modify his physiognomy, he entered Salzburg, accompanied by two friends, traveling in second-class compartments. To avoid conversation with anyone, he absorbed himself in reading a newspaper, concealing his face as soon as an employee appeared at his door. Having safely crossed Vienna and Pest, cities dangerous to his incognito, he arrives in Baziaş, where he must take a boat down the Danube. However, troop movements that were being mobilized suspended the crossing service. As a result, he is forced to stay overnight in a rather dirty inn, where the guests eat their meals at the communal table. Some of the guests made disparaging remarks about "Charles of Hohenzollern", predicting that he would be hunted like Cuza. On May 20, after spending his time writing letters and dispatches, he manages to embark with his two companions. Sitting on the second-class deck, amid sacks of cargo, he continues to write his correspondence. At Orșova, he has to transfer to a boat specially designed to withstand passage through the dreaded Iron Gates. At 4 p.m., after having to jostle a captain who pointed out that his ticket was stamped for Odessa and wanted to prevent him from disembarking, Charles steps onto Romanian soil for the first time in the small port town of Drobeta-Turnu Severin.[86] Brătianu bows to him and asks him to join his carriage.[87]

Inauguration of the reign of Carol I

On May 22, 1866 (May 10 according to the Julian calendar), Charles, renamed Carol I, entered Bucharest. News of his arrival had been transmitted by telegraph, and he was greeted by crowds eager to see their new sovereign. In Băneasa, a village north of Bucharest, he receives the keys to the city. In a premonitory sign, it rained that very day, after a long period of drought. He pronounced his vows to the chamber in French: "I swear to protect the laws of Romania, to uphold her rights and the integrity of her territory",[88] and addressed a few words justifying his acceptance: "Elected by the free impulse of the nation as Prince of Romania, I left my country and my family without hesitation. I am now a Romanian. Acceptance of the plebiscite imposes important duties on me, and I hope to fulfill them. I bring a loyal heart, sincere intentions, a firm will to do good, boundless devotion to my new homeland and unshakeable respect for the law. I'm ready to share the country's good and bad fortune: between us, everything will be common. Let us be fortified by unanimity; let us strive to rise to the occasion."[89]

Turkey protested against the installation of the Prince of Hohenzollern, but the conference of Danubian principalities held in Paris on May 25, 1866, merely acknowledged Ottoman disapproval without taking any further action.[90] Russia and France spoke out against any intervention, with France adding that events should be left to develop in Romania without recognizing the new prince,[91] but potentially allowing the fait accompli to triumph.[92] As for Turkey, despite contesting the election, it understood that to oppose it by force would only resurrect a crisis in the East and break the ties that bound it to Romania. On the contrary, the election of the Prince of Hohenzollern seemed to offer guarantees for the stability of the region. Turkey therefore refrained from intervening militarily in the Romanian provinces[93] and decided to recognize Prince Charles of Hohenzollern as sovereign of Romania on July 8, 1866.[94] Turkey also granted the principle of heredity to Prince Charles and his direct descendants.[95]

Aftermath of Carol I's election

New Constitution

On June 13, 1866, Carol promulgated the new Romanian Constitution, based on the model of the Belgian constitution, considered the most liberal in Europe. Article 82 stipulated that "the Prince's constitutional powers shall be hereditary in the direct and legitimate descendants of His Highness Prince Charles I of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, from male to male, in order of primogeniture, and to the perpetual exclusion of women and their descendants. His Highness's descendants will be brought up in the Eastern Orthodox religion".[96]

From her marriage to Elisabeth of Wied in 1869, however, Carol had only one daughter, Marie, who died before her fourth birthday in 1874.[97]

Romanian independence

From the outset of his reign, Carol I aimed for complete independence from the Ottoman Empire. In 1877, when the Russian Empire went to war against the Ottomans, Romania fought alongside the Russians. The military campaign was long, but victorious, and led to the country's independence, recognized by the Treaty of San Stefano and then at the Congress of Berlin in 1878. However, the new state once again lost Budjak to Russia, but acquired two-thirds of Dobrogea. Carol was crowned King of the new Kingdom of Romania in May 1881, and, by naming his nephew Ferdinand as heir, founded the dynasty of sovereigns who ruled Romania until 1947.[98]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The term "Hospodar" meaning "prince-sovereign" is rarely, if ever, used by Romanians, who prefer the term "Domnitor".

- ↑ Rural law divided peasants into three categories, according to the number of livestock they owned. Peasants received seven, four or two hectares in Wallachia; eight, six or three in Moldavia and nine, six or four in Bessarabia.

- ↑ The main points of the new electoral law stipulate that any Romanian aged 25 who can read and write and who can prove payment of an annual contribution of 4 ducats is a primary elector, and that parish priests, academy and college professors, doctors and graduates of various faculties, lawyers, engineers, architects, etc. may be elected direct electors without paying the 4 ducat contribution.

- ↑ Paul Henry (1896-1967) was director of the French University Mission in Paris, then of the Institute of Advanced Studies in Bucharest.

- ↑ The divan is made up of two Vornics (officers in charge of justice and internal affairs), the Grand Spătar (road maintenance and postal service), the Grand Vistier (treasurer) and the Logothète (chancellor for the various branches of administration).

- ↑ Charles de Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen's paternal grandmother was Antoinette Murat ; his maternal grandmother was Stéphanie de Beauharnais, herself the adopted daughter of Napoleon I.

- ↑ There is a separatist group in Moldavia led by Nicolae Rosetti-Roznovanu, Constantin D. Moruzi, Teodor Boldur Lǎțescu, Nicu Ceaur-Aslan, lawyers Alecu Cernea, Panaite Cristea, Alecu Spiru and Sandu Bonciu, joined by Metropolitan Primate Calinic Miclescu.

References

- ↑ "Charta Principateloru Unite ale României - Wikimedia Commons". commons.wikimedia.org. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

- ↑ Jean Luc Mayaud (2002). Actes du colloque international du cent cinquantenaire, tenu à l'Assemblée nationale à Paris, les 23-25 février 1998 (in French). Paris: Creaphis. p. 494. ISBN 9782913610217..

- ↑ I. Dumitri-Snagov (1982). Le Saint-siège et la Roumanie moderne: 1850-1866. Miscellanea Historiae Pontificiae (in French). Vol. 48. Rome: Universita gregoriana..

- ↑ "Traité de Paris - articles 22 et 23" (in French). 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ↑ Georgiade Mihail Obedenaru, "La Roumanie économique d'après les données le plus récentes" , Paris, Ernest Leroux, 1876, 435 p., p. 304.

- ↑ Journal du Palais: Lois, ordonnances, règlements et instructions d'intérêt général (in French). Vol. 6. Paris: Patris. 1858. p. 368.

- ↑ Démètre A.Sturdza; J.J. Skupiewski (1900). Actes et documents relatifs à l'Histoire de la régénération de la Roumanie (in French). Bucarest: Carol Göbl. p. 602.

- ↑ Anonyme (1866). Le panslavisme: Le prince Couza, la Roumanie, la Russie (in French). Paris: Dentu. p. 16.

- ↑ Lord Acton (1909). The Cambridge Modern History: The growth of Nationalities. Vol. XI. Cambridge: A.W. Ward. p. 644.

- ↑ Traian Sandu (2008). Histoire de la Roumanie (in French). Paris: Perrin. p. 152. ISBN 978-2262024321.

- ↑ Traian Sandu (2008). Histoire de la Roumanie (in French). Paris: Perrin. p. 154. ISBN 978-2262024321.

- ↑ Leanca, Gabriel (2011). La politique extérieure de Napoléon III (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. p. 10. ISBN 9782296555426.

- 1 2 3 Céline Lambert (2015). Les préfets de Maine-et-Loire (in French). Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes. p. 254. ISBN 9782753525566.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 A. Franck (1868). Notice sur la Roumanie principalement au point de vue de son économie rurale, industrielle et commerciale (in French). Paris. p. 436.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Stoica, Vasile (1919). The Roumanian Question: The Roumanians and their Lands. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Printing Company. pp. 69–70..

- ↑ "Correspondance de Bucarest", Journal de Bruxelles, n.129, 1864.

- ↑ David M.Crowe (2007). A History of The Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia. New York: St Martin's Griffin. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-4039-8009-0..

- ↑ Iancu, Carol (1980). "le problème juif à travers les documents diplomatiques français (1866-1880)". Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine. 27 (3): 391–407. doi:10.3406/rhmc.1980.1105. ISSN 0048-8003.

- ↑ "Situation extèrieure", L'Echo du Parlement, n.171, 1864.

- ↑ "Senatul în istoria României". Sénat de Roumanie (in Romanian). 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2020..

- ↑ Mario Rotondi (1976). Ciencia del derecho en el ultimo siglo (in French). CEDAM. p. 574..

- ↑ Bocşan, Mircea-Dan (2004). "Le Code Napoléon en Roumanie au siècle dernier". Revue internationale de droit comparé. 56 (2): 439–446. doi:10.3406/ridc.2004.19278. ISSN 0035-3337.

- ↑ Zlatescu, Victor Dan; Moroianu-Zlatescu, I. (1993). "Réflexions sur l'histoire du droit comparé en Roumanie". Revue internationale de droit comparé. 45 (2): 411–418. doi:10.3406/ridc.1993.4684. ISSN 0035-3337.

- ↑ Traian Sandu (2008). Histoire de la Roumanie (in French). Paris: Perrin. p. 140. ISBN 978-2262024321.

- 1 2 Bilteryst 2014, p. 156.

- ↑ "Histoire de l'hôpital de Colentina" (PDF). Istoric-Colentina (in Romanian). 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2020..

- ↑ Ivan T. Berend (2005). History Derailed: Central and Eastern Euroupe in the Long Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0520245259.

- ↑ Dan Popescu (1990). Icebergul: secvențe din epopeea dezvoltării (in Romanian). Bucarest: Albatros. pp. 83–84..

- ↑ Georges D. Cioriceanu (1928). La Roumanie économique et ses rapports avec l'étranger de 1860 à 1915 (in French). Paris: Jouve et Cie. p. 124..

- ↑ Emmanuel Starcky (2009). Napoléon III et les principautés roumaines (in French). Paris: RMN. pp. 102–106. ISBN 978-2711855803..

- ↑ Maria Georgescu, "La mission militaire française dirigée par les frères Lamy", Revue historique des armées, n.144, 2006, p.30-37

- ↑ Béla Borsi Kálmán (2018). Au berceau de la nation roumaine moderne - Dans le miroir hongrois: Essais pour servir à l'histoire des rapports hungaro-roumains aux XIXe et XXe siècles (in French). Archives contemporaines. p. 123. ISBN 9782813002754..

- ↑ « Principautés danubiennes », Journal de Bruxelles, no 139, 18 may 1864, p. 3

- ↑ "Nécrologie" L'Écho du Parlement, no140, 20 may 1873, p.2

- ↑ Emerit, Marcel (1972). "Cuza l'émancipateur". Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. 27 (3): 790. doi:10.1017/s0395264900167769. ISSN 0395-2649. S2CID 191735564.

- ↑ Silvia Marton (2003). La construction politique de la nation: La nation dans les débats du parlement de la Roumanie 1866-1871. Alma Mater Studiorum Universita'di Bologna (in French). Bologne: Archives contemporaines. p. 106..

- ↑ Archives diplomatiques 1866: Recueil de diplomatie et d'histoire (in French). Vol. 6. Paris: Librairie diplomatique d'Amyot. 1866. pp. 266–267..

- ↑ Auguste Ehrhard (1928). Le prince de Pückler-Muskau (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: Plon. p. 265..

- ↑ Frederick Kellogg (1995). The Road to Romanian Independence (1866—1914). West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-55753-065-3..

- ↑ Béla Borsi Kálmán (2018). Au berceau de la nation roumaine moderne - Dans le miroir hongrois: Essais pour servir à l'histoire des rapports hungaro-roumains aux XIXe et XXe siècles (in French). Archives contemporaines. pp. 123–124. ISBN 9782813002754..

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sturdza, Mihai Dimitri (1971). "La Russie et la désunion des principautés roumaines, 1864-1866". Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique. 12 (3): 247–285. doi:10.3406/cmr.1971.1843. ISSN 0008-0160.

- ↑ "Nouvelles de Russie", L'Indépendance belge, no9, 9 janvier 1866, p.2

- 1 2 3 Justus Perthes (1867). Almanach de Gotha: annuaire généalogique, diplomatique et statistique. Vol. 104. Gotha: Justus Perthes. pp. 1111–1112.

- ↑ Traian Sandu (2008). Histoire de la Roumanie (in French). Paris: Perrin. p. 158. ISBN 978-2262024321.

- ↑ J.A. Vaillant, La Roumanie: Histoire, langue, littérature, orographie, statistiques des peuples de la langue d'or, ardialiens, vallaques et moldaves résumés sous le nom de romans. II, Paris, Imprimerie de Fain et Thunot, 1844, 455 p., p. 229.

- ↑ Cécile Folschweiller (2020). Émile Picot, secrétaire du prince de Roumanie: Correspondance de Bucarest (1866-1867). Europe (in French). Paris: Presses de l'Inalco. p. 11. ISBN 978-2-85831-340-2..

- ↑ "Situation extérieure", L'Écho du Parlement, no67, 8 mars 1866, p.3

- ↑ Gafiţa, Irina (2015). "L'idiologie fractionniste. L'anti-dynasticisme". Hiperboreea. Journal of History. 2 (1): 133–151. doi:10.3406/hiper.2015.888. ISSN 2284-5666. S2CID 218418881.

- ↑ Leanca, Gabriel (2011). La politique extérieure de Napoléon III (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. p. 28. ISBN 9782296555426..

- ↑ "Principautés danubiennes", Le Bien Public, no64, 5 march 1866, p.2

- 1 2 3 4 Ionel Munteanu, «Une candidature avortée au trône de Roumanie", Museum Dynasticum, vol. XXIX, n.2, 2017, p.3.

- ↑ "Bulletin de la bourse de Londres du 27 février", L'Écho du Parlement, no62, 3 mars 1866, p.3

- ↑ Hitchins, Keith (1994). Rumania: 1866 - 1947. Oxford history of modern Europe. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822126-5.

- 1 2 Dan Berindei (2002). Les Roumains et la France au carrefour de leur modernité: Études danubiennes (in French). Bucarest. p. 168.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ↑ Kremnitz 1899, p. 9.

- ↑ Olivier Defrance (2004). Léopold Ier et le clan Cobourg. Les racines de l'Histoire. Bruxelles: Racine. p. 348. ISBN 978-2-87386-335-7.

- ↑ Carol I (1992). Memoriile Regelui Carol I al României: de un martor ocular. Istorie & politică (in Romanian). Bucarest: Scripta. p. 8. ISBN 978-9739541411..

- ↑ Bilteryst 2014, pp. 120–123.

- ↑ Bilteryst 2014, p. 157.

- ↑ Emmanuel Beau de Loménie (1937). Naissance de la nation roumaine (in French). Paris: Leroux..

- ↑ Leanca, Gabriel (2011). La politique extérieure de Napoléon III (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. pp. 10–12. ISBN 9782296555426..

- ↑ "Bulletin de la bourse de Londres du 27 février", L'Echo du Parlement, n.60, 1st march 1866, p.3

- 1 2 "Situation extérieure", L'Écho du Parlement, no67, 8 march 1866, p.3

- ↑ Gerhard, Hilke (1965). "Russlands Haltung zur rumänischen Frage, 1864-1866". Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Martin Luther Universität. 14 (4). doi:10.1515/9783486764987. ISBN 9783486764987.

- ↑ "Nouvelles de France", L'Indépendance belge, no67, 8 march 1866, p.3

- ↑ Gustave Léon Niox (1874). Expédition du Mexique, 1861-1867; récit politique & militaire. Paris. p. 550.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ↑ "Situation extérieure", L'Indépendance belge, no61, 12 march 1866, p.1

- ↑ "Situation extérieure", L'Indépendance belge, no77, 18 mars 1866, p.2

- ↑ Émile Ollivier (1902). La Première candidature Hohenzollern (1866) (in French). Paris. pp. 768–802.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ↑ Michel Huberty; Alain Giraud; Bruno Magdelaine (1988). L'Allemagne dynastique. Le Perreux-sur-Marne. p. 207.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Kremnitz 1899, p. 10.

- ↑ Stelian Neagoe (2007). Oameni politici români (in Romanian). Bucarest: Editura Machiavelli. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-973-8200-49-4..

- ↑ Kremnitz 1899, pp. 10–12.

- ↑ Dumitru Suciu (1993). From the Union of the Principalities to the Creation of Greater Romania. Cluj-Napoca: Center for Transylvanian studies, the Romanian Cultural Foundation. p. 26..

- ↑ "Bulletin télégraphique", L'Indépendance belge, no112, 22 avril 1866, p.2

- 1 2 Catherine Durandin (1995). Histoire des Roumains (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2213594255..

- ↑ Constantin Iordachi (2019). Liberalism, Constitutional Nationalism and Minorities: The Making of Romanian Citizenship c.1750-1918. Leiden, Boston: Brill. p. 227. ISBN 9789004358881.

- ↑ Frederick Kellogg (1995). The Road to Romanian Independence (1866—1914). West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-55753-065-3.

- ↑ "Bulletin télégraphique", L'Écho du Parlement, no107, 17 avril 1866, p.3

- ↑ "Nicolae Rosetti-Roznovanu" (in Romanian). 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ "Principautées danubiennes", Le Bien Public, no109, 19 avril 1866, p.3

- ↑ "Situation extérieur", L'Écho du Parlement, no109, 19 avril 1866, p.1

- ↑ Frederick Kellogg, , West Lafayette, Purdue University Press, 1995, 265 p. (ISBN 978-1-55753-065-3), p. 21.

- ↑ "Principautés danubiennes", Journal de Bruxelles, no112, 22 avril 1866, p.2

- ↑ "Revue politique", L'Indépendance belge, no141, 20 mai 1866, p.1

- ↑ E. Ucciani, «Comment Carol arriva au throne de Roumanie», L'Écho de la Presse, no191, 19 july 1915, p.1

- ↑ Paul Lindenberg (2016). Regele Carol I al României (in Romanian). Bucarest: Editura Humanitas. ISBN 978-97350-5336-9..

- ↑ Samuel Tomei and Sylvie Brodziak, "Dictionnaire Clemenceanu", Paris, Groupe Robert Laffont, 2017, 1105 p. (ISBN 9782221128596), article Romania.

- ↑ « Bucarest », L'Indépendance belge, no 145, 25 may 1866, p. 3

- ↑ "Bucarest", L'Indépendance belge, no146, 26 mai 1866, p.3

- ↑ "Revue politique", L'Indépendance belge, no147, 27 may 1866, p.1

- ↑ "Nouvelles de France", L'Indépendance belge, no149, 31 may 1866, p.2

- ↑ "Revue politique", L'Indépendance belge, no166, 15 juin 1866, p.1

- ↑ "Dépeche de Constantinople", L'Indépendance belge, no191, 10 juillet 1866, p.3

- ↑ "Revue politique", L'Indépendance belge, no195, 14 juillet 1866, p.1

- ↑ "Roumanie Constitution des provinces unies" (in French). 13 June 1866. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ↑ Michel Huberty; Alain Giraud; Bruno Magdelaine (1988). L'Allemagne dynastique: Hohenzollern-Waldeck (in French). Le Perreux-sur-Marne. p. 245.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Michel Huberty; Alain Giraud; Bruno Magdelaine (1988). L'Allemagne dynastique: Hohenzollern-Waldeck (in French). Le Perreux-sur-Marne. p. 268.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Bibliography

- Bilteryst, Damien (2014). Philippe Comte de Flandre: Frère de Léopold II (in French). Bruxelles: Éditions Racine. ISBN 978-2-87386-894-9.

- Béla Borsi Kálmán (2018). Au berceau de la nation roumaine moderne - Dans le miroir hongrois: Essais pour servir à l'histoire des rapports hungaro-roumains aux XIXe et XXe siècles (in French). Archives contemporaines. ISBN 9782813002754.

- Olivier Defrance (2004). Léopold Ier et le clan Cobourg. Les racines de l'Histoire. Bruxelles: Racine. ISBN 978-2-87386-335-7.

- Catherine Durandin (1995). Histoire des Roumains (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2213594255.

- A. Franck (1868). Notice sur la Roumanie principalement au point de vue de son économie rurale, industrielle et commerciale (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kremnitz, Mite (1899). Reminiscences of the King of Roumania. New York et Londres: Harper and brothers.

- Leanca, Gabriel (2011). La politique extérieure de Napoléon III (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 9782296555426.

- Traian Sandu (2008). Histoire de la Roumanie (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2262024321.

- Emmanuel Starcky (2009). Napoléon III et les principautés roumaines (in French). Paris: RMN. ISBN 978-2711855803.

- G.-H. Dumont, "Quand le Prince Philippe, Comte de Flandre, refusait le trone de Roumanie" ,Museum Dynasticum, vol. V, no 2, 1993, p. 11-19.

- Maria Georgescu, "La mission militaire francaise dirigée par les fréres Lamy", Revue historique des armées, no 244, 2006, p. 30-37

- Ionel Munteanu, "Une candidature avortée au throne de Roumanie", Museum Dynasticum, vol. XXIX, no 2, 2017, p. 3-12

- Mihai Dimitri Sturdza, "La Russie et la désunion des principautés roumaines 1864-1866", Cahiers du monde russe, vol. 12, no 3, 1971, p. 247-285