| Elizabeth Bay House | |

|---|---|

Façade of Elizabeth Bay House | |

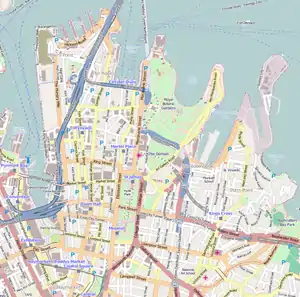

Location in Sydney | |

| Etymology | Elizabeth Bay |

| General information | |

| Status | Used as a museum |

| Type | Government home |

| Architectural style | Australian Colonial Regency |

| Address |

Elizabeth Bay, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Country | Australia |

| Coordinates |

|

| Construction started |

|

| Completed |

|

| Renovated | 1977 (house) |

| Client | Alexander Macleay, NSW Colonial Secretary |

| Owner | Sydney Living Museums |

| Landlord | Office of Environment and Heritage, Government of New South Wales |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Main contractor | James Hume |

| Renovating team | |

| Architect(s) | Fisher Lucas |

| Other information | |

| Parking | No parking; public transport: |

| Website | |

| sydneylivingmuseums | |

| Official name | Elizabeth Bay House |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Criteria | a., c., d., e., f., g. |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 6 |

| Type | Other - Residential Buildings (private) |

| Category | Residential buildings (private) |

| Builders | James Hume |

| Official name | Elizabeth Bay House Grotto Site and works; Carriageworks |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 116 |

| Type | Garden Residential |

| Category | Parks, Gardens and Trees |

| Builders | Convict and free artisans under the direction of John Verge |

| References | |

| [1][2][3][4] | |

Elizabeth Bay House is a heritage-listed Colonial Regency style house and now a museum and grotto, located at 7 Onslow Avenue in the inner eastern Sydney suburb of Elizabeth Bay in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. The design of the house is attributed to John Verge and John Bibb and was built from 1835 to 1839 by James Hume. The grotto and retaining walls were designed by Verge and the carriage drive on Onslow Avenue was designed by Edward Deas Thomson and built from 1832 to 1835 by convict and free artisans under the direction of Verge. The property is owned by Sydney Living Museums, an agency of the Government of New South Wales. Known as "the finest house in the colony", Elizabeth Bay House was originally surrounded by a 22-hectare (54-acre) garden, and is now situated within a densely populated inner city suburb.[1][2]

Elizabeth Bay House is a superb example of Australian colonial architecture, best known for its central elliptical saloon with domed lantern and geometric staircase, and was listed on the (now defunct) Register of the National Estate[3] and was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1][2]

History

Elizabeth Bay / Gurrajin

Elizabeth Bay had been the site of a fishing village established by Governor Macquarie (1810–21) in c. 1815 for a composite group of Cadigal people – the indigenous inhabitants of the area surrounding Sydney Harbour – under the leadership of Bungaree (d. 1830). Elizabeth Bay had been named in honour of Mrs Macquarie. Bungaree's group continued their nomadic life around the harbour foreshores. Sir Thomas Brisbane, Governor 1821–25, designated Elizabeth Bay as the site of an asylum for the insane. A pen sketch by Edward Mason from 1822 to 1823 shows a series of bark huts for the natives' in the locality.[1][2][5]: 38 [6]

Alexander Macleay

Alexander Macleay (1767–1848), public servant and entomologist, was born at Wick, a fishing village in Ross-shire, Scotland. He moved to London in 1786, marrying Elizabeth Barclay there in 1791. Macleay, who was employed in the civil service (1795–1825) was well known in British and European natural history circles, having amassed by 1805 one of the most significant insect collections in Britain. He was elected a fellow of the Linnean Society of London in 1794 commemorating the great Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus, whose Species Plantarum (1753) became the internationally accepted starting point for all botanical nomenclature and served as its secretary from 1798 to 1825. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1809. Botanist Robert Brown, Macleay's close friend and suitor of his eldest daughter Fanny, a competent botanical artist, named the plant genus Macleaya in his honour.[1][2]

In enforced retirement from 1817 when his department was abolished at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Macleay's finances were stretched to support a large family (10 of 17 children survived to adulthood), town and country residences, and his obsessive collecting of insects. When assets had to be sold upon the collapse of his brother's private bank in Wick, in which Alexander was a partner, he began in 1824 to borrow heavily from his eldest son, William.[1][2]

Macleay accepted the position of NSW Colonial Secretary, arriving in 1826 and moving into the Colonial Secretary's house (fronting Macquarie Place) with his wife Eliza, their six surviving daughters, an extensive library, and an insect collection then "unparalleled in England" for its size, range and number of type specimens (first to be named of a species). Three of the four surviving sons came later to NSW, of whom two, William and George – shared their father's natural history interests. (From the early 1820s the spelling Macleay was adopted; descendants of Alexander's brothers retained MacLeay or McLeay).[1][2]

Soon after his arrival in 1826 he was granted 22 hectares (54 acres) by Governor Darling at Elizabeth Bay, with commanding views of Sydney Harbour. It was usual practice for grants to be made to eminent citizens in the colony but Macleay's grant generated some heated editorials in Sydney's newspapers. It involved the alienation of public land, the former Aboriginal settlement of Elizabeth Town, later earmarked for an asylum.[1][2]

The Estate

In 1826 Macleay set about improving the site, using assigned convict labour. He employed his horticultural expertise, assisted from the late 1820s by gardener Robert Henderson, to establish a private botanic garden with picturesque features of dwarf stone walls, rustic bridges, and winding gravel walks.[7] This was amid the existing native vegetation.[1][8]

In May 1831 The Sydney Gazette enthusiastically reported improvements at Woolloomooloo Hill (Potts Point) and Macleay's neighbouring estate at Elizabeth Bay "5 years ago the coast immediately eastward of Sydney was a mass of cold and hopeless sterility, which its stunted and unsightly bushes seemed only to render the more palpable; it is now traversed by an elegant carriage road and picturesque walks.[1]

That these rapid improvements were originated by the proprietor of Elizabeth Bay cannot be doubted. He was the first to show how these hillocks of rock and sand might be rendered tributary to the taste and advantage of civilized man. As to the estate of Elizabeth Bay, no one can form an adequate judgement of the taste, labour and capital that have been bestowed upon it. A spacious garden, filled with almost every variety of vegetable; a trellised vinery; a flower garden, rich in botanical curiosities, refreshed with ponds of pure water and overlooked by fanciful grottoes; a maze of gravel walks winding around the rugged hills in every direction, and affording sometimes an umbrageous solitude, sometimes a sylvan coup d'oeil, and sometimes a bold view of the spreading bays and distant headlands – these are living proofs that its honourable proprietor well deserved the boon, and has well repaid it."[1][5][6]

As with the design of the house, the design of the estate appears to have involved a number of people whose respective contributions are not known. Fanny Macleay regarded her father as the mastermind, referring to Elizabeth Bay as "our Tillbuster the second", a reference to the Macleay family's country estate in Godstone, Surrey, which Alexander had improved in 1817. In September 1826 she promised her brother a plan of the recently acquired grant "when Papa has decided where our house is to be and the garden etc". Although Nurseryman Thomas Shepherd had practised as a landscape gardener many years previously in England and his 1835 (public) lecture (in Sydney) included suggestions for the further improvement of the Elizabeth Bay estate, he does not claim credit for involvement, however informal, in its design. It may be that Macleay considered his views old-fashioned.[1]

In 1825 Robert Henderson had been recruited at the Cape of Good Hope by Alexander Macleay. Henderson's obituary records that he superintended the laying out of the gardens of Elizabeth Bay and Brownlow Hill. In February 1829 Fanny wrote "we have now some beautiful walks thro' the bush. Mr (Edward) Deas-Thompson who is possessed of an infinity of good taste is the Engineer and takes an astonishing degree of interest in the improvement of the place."[1]

John Verge's office ledger contains many references to the design of garden structures, including gates and piers and copings and "scroll ends" for garden walls. The entries are dated between April and November 1833. A design for a bathing house (not built) dated 1834 and initialled "R.R.", may be attributed to the architect and surveyor, Robert Russell (1808–1900) who arrived in Sydney in that year.[1]

Macleay's approach to the Australian bush was in contrast with that of the majority of colonists, who customarily cleared it and started afresh. Nurseryman Thomas Shepherd wished others to emulate this:[1]

The high lands and slopes of this property are composed of rocks, richly ornamented with beautiful indigenous trees and shrubs. From the first commencement he (Macleay) never suffered a tree of any kind to be destroyed, until he saw distinctly the necessity for doing so. He thus retained the advantage of embellishment from his native trees, and harmonised them with foreign trees now growing. He has also obtained the benefit of a standing plantation which it might otherwise have taken twenty or thirty years to bring to maturity.

The bush was planted with specimen orchids and ferns to enhance its botanical interest, which could be enjoyed in the course of a "wood walk". Two surviving notebooks[9] list the sources of plants for the garden and illustrate a comprehensive approach to plant collecting, similar in their approach to entomology. The plant and seed books contain entries for purchases from nurserymen Messr.s Loddiges of Hackney, London, and exchanges with William Macarthur of Camden Park. They also record the plants contributed by visitors to the estate and by William Sharp Macleay's natural history collectors in India.[1]

Alexander Macleay had a great passion for bulbous plants, particularly those from the Cape of Good Hope. The explorer Charles Sturt, contributed many bulbs collected on his journey to South Australia in 1838, having been presented with four bulbs of Calostemma album from the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew during his visit to Elizabeth Bay in February 1831. Bulbs featured in the large collection of plants which William Sharp Macleay brought with him to Australia in 1839. 88 varieties of bulbs were forwarded to him in 1839-40 by his scientific correspondent, Dr Nathaniel Wallich, Superintendent of the botanical garden in Calcutta.[1]

Macleay's garden was also noted for its fruit trees. In 1835, Charles Von Hugel noted "pawpaw, guava and many plants from India were flourishing". Georgianna Lowe (of Bronte House) described the shrubbery and adjacent garden, in 1842–43 commenting on the wealth of fruit trees and other plants assimilated into a Sydney garden: "Mr Macleay took us through the grounds; they were along the side of the water. In this garden are the plants of every climate – flowers and trees from Rio, the West Indies, the East Indies, China and even England. And unless you could see them, you would not believe how beautiful the roses are here. The orange trees, lemons, citrons, guavas are immense, and the pomegranate is now in full flower. Mr Macleay also has an immense collection from New Zealand."[1]

Many visitors commented on Macleay's achievement in creating a garden in Sydney conditions. Georgianna Lowe described "some drawbacks to this lovely garden: it is too dry, and the plants grow out of a white, sandy soil. I must admit a few English showers would improve it."[1][5]

Macleay received the Yulan magnolia (M. denudata), a small tree from south-eastern China, at Elizabeth Bay, in 1836.[1][10]

The Villa

Plans for the villa were in hand from 1832 but construction did not commence until 1835. Elizabeth Bay House was built between 1835 and 1839 by the accomplished architect and builder John Verge. It is believed that Verge worked from plans acquired from a British source prior to 1832. Macleay, in addition to his post, was an entomologist of standing in the world of natural science and had been secretary (1798–1825) of the prestigious Linnean Society in London. He brought with him his huge insect collection, a library of 4000 works and a wide knowledge of horticulture and botany.[1]

The internal design of the house was loosely modelled on Henry Hollands Carlton House built c. 1820 for the Prince Regent in London. Macleay could not afford the intended encircling colonnade. The house's architectural significance rests largely with its interior, owing to its state of incompletion. A planned encircling colonnade was not built. It is possible that Macleay's son William Sharp, after his examination of his father's finances upon joining the family in Sydney in 1839, called for a halt to the building of the house.[1]

When the house was finished in 1839 it was occupied by Alexander, his wife Eliza, their unmarried daughter Kennethina, unmarried son William Sharp, the Macleay's nephews William and John and two Onslow grandchildren. Their five other daughters had married. At the same time wool prices dropped and transportation ended in 1840 and the colony was plunged into depression. Macleay was already in debt. The depression, these debts, the capital he had outlaid on the house and garden, the expenses of his various country properties and the loss of his large official salary brought about by early retirement meant that by the early 1840s he was in financial difficulties.[7][1]

William Sharp Macleay in 1839 was in London and ordered furnishings for the drawing room of Elizabeth Bay House. Six years later in 1845 in the midst of a colonial financial crisis, he sold them to the newly completed Government House, Sydney, where three of the original rosewood veneer tables still have pride of place. The furnishings included pelmets with gilt "cornices" (curtain pelmets in this case, with Louis XIV- revival scrolls and a Greek-Revival egg and dart cresting) which were transferred to Government House also.[11][1]

Recent research demonstrates that the main axis of the house is perfectly oriented and aligned to the position of the sunrise at the winter solstice or shortest day of the year – so that the rising sun bisects the house, running through the front door, out the rear door and hitting the sandstone cliff face at the rear of the house. The architraves and stone flooring along the central corridor are evenly illuminated, lasting only for a minute. For over two weeks either side of the winter solstice the effect may be observed with varying luminance and duration, as the sun's elevation and position on the horizon changes.[12] Though no documents are known to discuss this feature, it is not likely to be an accident.[1][13]

The garden became known internationally through the letters and published accounts of local naturalists and visiting scientific expeditions:[1]

the drive to the house is cut through rocks covered with splendid wild shrubs and flowers of this country, and here and there an immense primeval tree In this garden are the plants of every climate – flowers and trees from Rio, the West Indies, and even England. The bulbs from the Cape (of Good Hope) are splendid – you would not believe how beautiful the roses are here – Mr Macleay has also an immense collection from New Zealand.

Botanist Joseph Hooker (Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 1865–85) described the garden in 1841 as "a botanist's paradise My surprise was unbounded at the natural beauties of the spot, the inimitable taste with which the grounds were laid out and the number and rarity of the plants which were collected together." Macleay corresponded with and sent indigenous plant specimens to Kew, donated exotic plants to the Sydney Botanic Gardens, supplied trees to nurseryman Thomas Shepherd, exchanged plants with William Macarthur at Camden Park, encouraged local naturalists, and promoted exploration. As a member of numerous public and charitable committees, he exerted considerable influence in the establishment of the Australian Museum, the Australian Subscription Library, and more particularly on policy at the Botanic Gardens.[1]

Macleay, who had served diligently as Colonial Secretary, was ousted from office by Governor Bourke in 1837. The loss of salary contributed to his financial problems: British debts were unpaid; mortgages that had funded the lavish expenditure on both Elizabeth Bay House and Brownlow Hill, his country house near Camden, were due: pastoral ventures failed in the 1840s depression.[7][1]

An attempt was made to subdivide the land in 1841 but the blocks did not sell. While others were forced to declare bankruptcy, Macleay was saved by his eldest son William Sharp Macleay, also Alexander Macleay's largest creditor. In 1845 W. S. Macleay insisted his family move out of the house and then took it over the payment of the debts himself. Macleay's library and the drawing room furniture were sold to pay creditors. William Sharp Macleay (1792-1865), public servant, scholar and naturalist, and eldest son, inherited his father's insect collection, and stayed alone at the house until his death in 1865. Alexander and Eliza moved, bitterly, to Brownlow Hill. He was elected Speaker of the Legislative Council (1843–46). Injured in a carriage accident in 1846, and still suffering the effects, he died at Tivoli, Rose Bay, the home of one of his daughters. George Macleay (1809-1891) pastoralist and explorer and third surviving son, inherited his father's debts.[1]

Two contrasting personalities, William, a Cambridge classical scholar, controversial pre-Darwinian theorist, author and contributor to leading scientific journals, and recluse: and George, a pragmatist, and subsequently a peripatetic bon vivant; the brothers, individually and jointly, contributed to NSW's scientific and horticultural advancement. Both were involved with the Botanic Gardens, Australian Museum and, beginning with their father, maintained an unbroken connection with the Linnean Society of London (1794-1891).[1]

William arrived in 1839 in NSW with important collections of insects from South America (on which he published) and from Cuba where he was posted by the British Government (1825–36), as well as a large collection of plants. At Elizabeth Bay, two notebooks of plants and seeds exchanged, imported or desired for its garden, which he compiled with his father, reflect the extent of their horticultural pursuits and provide vital records of this outstanding colonial garden. William was a corresponding member of the Royal Botanic Society of London. During his residency at Elizabeth Bay – with the family from 1839 and alone from 1845 – the house continued as a favoured location for local and visiting scientists and Sydney's intellectual circle. William Sharp Macleay died unmarried, leaving the estate to George and the insect collection to his cousin William John Macleay.[7][1]

Visiting esteemed English nurseryman John Gould Veitch describes in an 1864 journal entry, Elizabeth Bay House's garden as one of "few private gardens in Sydney where gardening is carried on with any spirit. Those of Mr Thomas Mort, of Darling Point, the late Mr William Macleay of Elizabeth Bay and Sir Daniel Cooper of Rose Bay, formerly contained good collections of native and imported plants, but now they are no longer kept up.".[14][1]

After William Sharp's death in 1865 George Macleay inherited the estate (he had moved to England after 1859, when the trustees had been able to settle the estate. A keen zoologist, George had donated specimens to his brother and to the Australian Museum; he presented the papers of his father and his brother William Sharp to the Linnean Society of London and through Charles Nicholson, Greek statuary to the University of Sydney. George progressively subdivided the estate and sold leaseholds of a substantial portion and leased the house to his cousin William John Macleay and his wife Susan.[1]

William John (1820–1891) pastoralist, politician, patron of science, and nephew of Alexander, was born in Wick, came to NSW with his cousin William Sharp Macleay in 1839, and became a squatter with extensive pastoral runs in the Murrumbidgee whose profits would ultimately fund the scientific interests engendered by his uncle and cousins. He was a member of the Legislative Assembly (1856–74), a trustee of the Australian Museum (1861–77), and in 1862 helped found the Entomological Society of NSW. In 1865 he inherited the insect collections of Alexander and W. S. Macleay and leased Elizabeth Bay House, living there with his wife Susan. William John, like the Macleays who had lived in the house before him, was an ardent collector, sponsoring collecting expeditions including that of the "Chevert" to New Guinea in 1875, and broadening the collection from insects and marine invertebrates to encompass all branches of the natural sciences (such as birds and reptiles). Encouraging the study of botany, he was the first president of the Linnean Society of NSW (1874). The Linnean Society of NSW presented the Macleay's early plant and seed books to the Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW.[7][1]

By 1875 the Macleay family collections at the house were now so large that William John had a curator George Masters appointed to look after the collection. In 1889 the collections were presented to the Macleay Museum at the University of Sydney, where the government built a museum (1886–88) to which the collections were transferred, together with some original collector's cabinets, library, Macleay papers, and an endowment for a curator (this remains as the Macleay Museum). W. J. Macleay was knighted in 1889 and died in 1891, leaving substantial bequests to various institutions including the University of Sydney and the Linnean Society of NSW. His wife stayed there until her death in 1903. The couple had no children. After the death of George Macleay in 1891, under the terms of William Sharp Macleay's will, the house was passed from their nephew Arthur Alexander Walton Onslow who had died, to his eldest son James Macarthur Onslow of Camden Park. By this time the 22-hectare (54-acre) estate had shrunk to 7.5 hectares (19 acres) through successive subdivisions. Members of the Macleay family occupied Elizabeth Bay House until 1903.[1]

Twentieth century

In 1927 the remainder of the land around the house was sold. In this final division the kitchen wing at the rear of the house was demolished to allow an access road for allotments behind the house. By 1934 the house and eleven lots remained unsold due to the depression. Artists squatted in the house until 1935 when it was purchased, renovated and refurbished as a reception house. Five years later the house was again altered to accommodate fifteen flats.[1]

From 1948 to 1950 Sydney City Council using landscape architect Ilmar Berzins created the Arthur MacElhone Reserve on what had been Elizabeth Bay House's famous lawn (three lots, unsold in the 1927 subdivision). Macleay had created a broadly elliptical levelled lawn at considerable cost. It was noted for containing every Cape bulb known in the colony in the 1840s. With the 1927 subdivision creating a new road of Onslow Avenue this lawn and the house's front address to it were bisected and a new sandstone retaining wall was made edging Onslow Avenue in front of the house and on its east and west. To the north-east a new road of Billyard Avenue also dating from 1927 edged the reserve.[1]

The Arthur MacElhone Reserve commemorates a City Councillor for this Fitzroy Ward. Berzins' design incorporated Macleay's curving retaining wall and protruding sandstone ledges or benches and a grotto facing onto the footpath on Billyard Avenue below. Some of the rich plant collection in this reserve is appropriate, given its proximity to Elizabeth Bay House and the range and richness of that former estate's shrubberies and gardens. Berzins is also known for designing Hyde Park, Sydney's Sandringham Gardens near the north-west corner of Park & College Streets in 1951 and Duntryleague Golf Club course, Orange.[15][1]

In 1961 the National Trust of Australia (NSW) started to list and publicise important historic places. Elizabeth Bay House was one of the first sixty places named.[13][1]

Architect John Fisher (early member of the Institute of Architects, Cumberland County Council Historic Buildings Committee and on the first Council of the National Trust of Australia (NSW) Board after its reformation in 1960) was commissioned by the State Planning Authority to restore Elizabeth Bay House, which led to the formation of the Historic Houses Trust of NSW in 1980.[16] A Friends of Elizabeth Bay House group formed well before the formation of the Historic Houses Trust of NSW.[17][1]

In 1963 the Cumberland County Council purchased Elizabeth Bay House and essential repairs were carried out.

Refurbishment

The State Planning Authority assumed control in 1972 and it was decided to restore the house as an official residence for the Lord Mayor of Sydney.[13][1] A change of government signalled a change in policy and a decision that the house become a public museum. Architects Fisher Lucas supervised the restoration of the house which began in 1977.[18][1] In 1980 it was put in the care of a Trust before coming under ownership of the Historic Houses Trust of NSW in 1981.[18] It was one of the first properties acquired by the Historic Houses Trust of NSW.[13] Since then the Friends of Elizabeth Bay House and subsequent Friends of the Historic Houses Trust have raised funds and held events in support of the house's interpretation and enjoyement. These funds included new curtains and pelmets being installed in the drawing room ($25,000) and furnishing a maid's room ($10,000).[17][1]

The house was refurnished in the style of 1839–45, the interiors reflecting the lifestyle of the Macleays and presenting an evocative picture of early 19th century Sydney life. Largely in the Greek Revival style with elements of the Louis revival, the house's interiors have been recreated based on several inventories, notably an 1845 record of the house's contents and a list of furniture sold to the newly completed Government House, plus pieces known to have originated at the house that is now located at Camden Park or Brownlow Hill (originally the Macleays' country property near Camden, NSW). The large library contains several insect cases and a desk originally owned by Macleay, on loan from the Macleay Museum at Sydney University. Wall colours have been determined from paint scrapes that revealed the original colour schemes. The house also contains a collection of significant early Australian furniture from Sydney and Tasmania.

A nearby grotto, with accompanying stone walls and steps, plus several trees, are all that remain of the original extensive garden, which contained Macleay's considerable native and exotic plant collection, an orchard and kitchen garden. A hand-written notebook of "Plants received at Elizabeth Bay" in the collection of the Mitchell Library, is indicative of the original collection.

Modern history and use

In 2010–11, the house was used as the set for the music video of Jessica Mauboy's single "What Happened to Us" featuring Jay Sean. The song was one of Mauboy's biggest hits at the time.[19] In November 2020, Hayley Mary from The Jezabels released the video to her single The Chain, which was directed by Tyson Perkins and filmed at Elizabeth Bay House. Elizabeth Bay House is available for hire as a reception venue and is often used for wedding receptions.

Description

Elizabeth Bay House is a Greek Revival villa with a centralised Palladian layout with two levels, two unconnected cellar wings beneath the house and attic rooms under the roof. It is built of soft Sydney sandstone with a protective coat of sand paint. There is a square entrance vestibule leading into an oval, domed saloon around which a cantilevered stair rises to an arcaded gallery. The Australian Cedar joinery is finely moulded and finished simply with wax polish. The timber floors throughout are Australian Blackbutt. There is an original, large brass door lock on the front door.[1]

The house's facade is severe, owing to its incomplete nature: like many colonial houses begun in the late 1830s, the house is unfinished, the victim of Macleay's growing financial distress and the severe economic depression of the 1840s.[4] It was originally intended to have an encircling single-storey Doric colonnade (included in several views by Conrad Martens, and akin to the colonnade at Vineyard, designed by Verge for Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur); the small portico was only added in the early 20th century.[1]

The square entrance hall preludes the soaring space of the oval domed saloon. The entablatures and fluted pilasters of the doorways, the tapering Grecian architraves and panelled reveal shutters of the windows and the plaster cornice and frieze decorated with laurel wreaths. The stairway is of Marulan sandstone and built into the wall, resting on the tread underneath. The cast iron banisters are painted in imitation bronze. Eleven carved stone brackets support the first floor balcony. The portico is a light, single storeyed structure of iron and wood. Verge's attention to symmetry can be seen in the blind windows constructed on the walls of both sides of the house.[1][20]: 10–12, 21, 24

Recent research demonstrates that the house is perfectly oriented and aligned to the position of the sunrise at the winter solstice or shortest day of the year - so that the rising sun bisects the house, running through the front door, out the rear door and hitting the sandstone cliff face at the rear of the house. The architraves and stone flooring along the central corridor are evenly illuminated, lasting only for a minute. For over two weeks either side of the winter solstice the effect may be observed with varying luminance and duration, as the sun's elevation and position on the horizon changes.[1][21][12]

Pelmets with gilt "cornices" (curtain pelmets in this case, with Louis XIV- revival scrolls and a Greek-Revival egg and dart cresting) have been recreated for the drawing room, based on 1839 original pelmets ordered in London by William Sharp Macleay. In 1845 Macleay sold these to the newly completed Government House, Sydney where three of the original drawing room furnishings, being rosewood veneer tables, still have pride of place.[11][1]

A rear service wing (since demolished) contained a kitchen, laundry and servants' accommodation, and a large stables (also demolished) was sited elsewhere on the estate. A design for a proposed bathing pavilion imitated the Tower of the Winds in Athens. The pavilion was intended for the extremity of nearby Macleay Point, facing Rushcutters Bay and which was poetically named Cape Sunium after the peninsula east of Athens with its picturesque ruined temple.

The designer of the house is uncertain, with recent research suggesting that the accomplished colonial architect John Verge (1788–1861) was the main designer, but that he was presented with an imported scheme that he modified for Macleay. The fine detailing demonstrates the role of Verge's partner John Bibb.

Condition

As at 22 September 1997, the physical condition was good. Elizabeth Bay House possesses a high level of intactness, including a very percentage of original plaster finishes and joinery.[22][1]

Modifications and dates

The following modifications to the site include:[1][23]

- 1841 – Subdivision of some of the Elizabeth Bay land

- 1865, 1875, 1882 – Further subdivisions

- 1892 – Balcony added to the house

- 1927 – Final subdivision

- 1935 – House renovated and refurbished

- 1941 – House altered to accommodate fifteen flats

- 1963 – Essential repairs carried out

- 1972–76 – Restoration of Elizabeth Bay House.

Heritage listing

House

As at 1 July 2005, Elizabeth Bay House is one of the most sophisticated works of architecture of the early 19th century in New South Wales, once known as "the finest house in the colony". Elizabeth Bay House's incomplete state reflects the 1840s depression which devastated a class of prominent colonial civil servants, pastoralists and merchants. The house is significant for its association with the history of the intellectual life of NSW in the areas of scientific (natural history, particularly entomology, botany) and aesthetic endeavour through its association with three generations of Macleay family.[1]

The layout of the former 22-hectare (54-acre) Elizabeth Bay estate provided the structure of the modern suburb Elizabeth Bay. Its subdivision reflected the fate of 19th century villas in the inner eastern suburbs of Sydney. The siting of Elizabeth Bay House and surviving elements of Elizabeth Bay Estate provide rare examples of sophisticated Landscape design in early 19th century NSW. In its heyday the garden was known internationally through the letters and published accounts of local naturalists and visiting scientific expeditions, as a fine private botanic garden with picturesque features of dwarf stone walls, rustic bridges, and winding gravel walks, and a fine plant collection of choice and rare species, particularly bulbs.[1]

The house has long been significant to the conservation movement in Australia. This is indicated by proposals to refurbish the house as a museum for the 1938 sesquicentenary of white settlement, Professor Leslie Wilkinson's ownership share in Elizabeth Bay Estates Limited (1926–1935), the acquisition of the property by the Cumberland County Council in 1963 for its historic significance and the 1972–76 restoration by Clive Lucas, one of the first modern, scholarly conservations in Australia.[22][1]

Elizabeth Bay House was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

Elizabeth Bay House and the estate are significant for their association with the history of intellectual life in NSW and their association with three generations of Macleay owners as well as members of the extended Macleay family. The house's association with Alexander Macleay reflects the exploration and settlement of Australia concurrently with the extraordinary growth in scholarly interest in the natural sciences at the end of the 18th century. Elizabeth Bay House and its garden were visited by prominent Australian, British, American and European scientists and intellectuals throughout most of the 19th century, being a focus for Australia's role in an international scientific community. The Macleay family and Macleay family collections provided key endowments for the Australian Museum, the Macleay Museum at Sydney University and the Linnean Society of NSW.[1]

The estate is the location of the Aboriginal settlement of Elizabeth Town, established by Governor Macquarie and under the leadership of Bungaree and is a significant Aboriginal-European contact site. Physical evidence of this is extant in the form of a midden behind blocks of flats between Onslow Avenue and Billyard Avenue. Elizabeth Bay House has representative associations with John Verge, the most fashionable architect in NSW during the 1830s and the artist Conrad Martens who executed views of the house and other commissions for members of the extended Macleay family. The house has associations with NSW high Victorian architect, George Allen Mansfield, who designed the portico, architect C. C. Phillips who provided designs for the conversion of the house into flats in the 1940s and conservation architect Clive Lucas who supervised the restoration and adaption of the house in 1972–76.[1]

The house has associations with the NSW Jewish community as it was the home of George Michaelis and his family, one of a number of prominent Jewish families which resided in villas in the vicinity of Elizabeth Bay, which was noted as within walking distance of the Great Synagogue. Elizabeth Bay has rare associations with the history of the visual arts in NSW. Between 1927 and 1935 a colony of artists squatted in the house and during 1940–41 after the conversion of the house to flats, the artist Donald Friend lived in the Morning Room flat. Friend was a resident of the house after it was vacated by the Macleay family and converted into residential flats.[4][22][1]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

Elizabeth Bay House is one of the finest domestic buildings erected in Australia in the early 19th century. The Saloon is arguably the finest interior in 19th century Australian architecture. The quality of the Greek Revival styling of the house marks a transition in John Verge's career from relatively restrained commissions such as Lyndhurst, Glebe, to more sophisticated designs such as Camden Park. The Greek Revival joinery is particularly fine. The siting of Elizabeth Bay House and surviving elements of Elizabeth Bay Estate provide rare examples of sophisticated Landscape design in early 19th century NSW. The estate, possibly laid out with advice from Landscape gardener Thomas Shepherd adapted design principles from the English 18th century Landscape movement to a Sydney harbourside setting with the retention of indigenous trees. Elizabeth Bay House's relationship with the villas Tusculum and Rockwall, Potts Point provides a rare key precedent for town planning in Australia. The 1826 grant of Elizabeth Bay House estate to Alexander Macleay was followed by the granting of a series of allotments along Macleay Street Potts Point to the colony's principal civil servants and one respectable merchant, under a series of villa conditions, which specified the quality and elements of the design of these houses. It is believed that both Alexander Macleay and Mrs Darling, wife of the Governor, took a key role in establishing the parameters for this development of Sydney's first suburb.[22][1]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

Elizabeth Bay House through its landmark siting and aesthetic qualities is held in great esteem by the residents of Elizabeth Bay and a wider eastern suburbs community. A broad community awareness of the location of the suburb on the subdivided Elizabeth Bay House estate is re-inforced by the survival of the drive/road network, elements of the terraced garden, late 19th century villas and early 20th century flats which followed on from these subdivisions. Elizabeth Bay House is held in esteem by a large number of former residents, the Jewish community and visual arts community in NSW. Elizabeth Bay House is held in great esteem by a broad heritage community in NSW.[22][1]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Elizabeth Bay House, while not an intact historic interior, possesses key areas of intact historic finishes and significant evidence of finishes in most rooms which allows its interpretation as a significant early NSW domestic interior. Significant elements of the early 19th century furnishing and Macleay collections survive in the collection of Government House, Sydney, and the Macleay Museum. A myriad of references to domestic furnishing and other aspects of Macleay life at Elizabeth Bay House has been collated and forms the basis of the present interpretation of the Macleay occupancy of Elizabeth Bay House during the period 1839–1845. Elizabeth Bay House provides a key example for the study of architectural patronage, domestic design and its sources in NSW. The attribution of the complete design to John Verge remains inconclusive, with Macleay's role as a client and possible unidentifiable British architect, British architectural pattern book sources and the work of James Hume and John Bibb requiring further research. Elizabeth Bay House has had a significant, albeit limited, impact on the architecture of NSW and the appreciation of colonial buildings through the developing conservation movement. Further research should reveal examples of buildings influenced by the house. Those already identified include Aberglasslyn, Vineyard and Engehurst. The house has a long-standing association with the NSW arts community. Between 1927 and 1972 the house was the home of a number of artists, including Justin O'Brien and Donald Friend. Research should establish a more complete record of Elizabeth Bay House's association with the arts community and the house's effect on the creative work of these individuals.[22][1]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Elizabeth Bay House is rare as one of the most sophisticated essays in the Greek Revival style favoured by John Verge.[22][1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

Elizabeth Bay House is a rare superlative example of a representative class of Greek Revival villas constructed by New South Wales' most fashionable architect, John Verge, for prominent colonial civil servants, pastoralists and merchants.[1]

Grotto and retaining walls

As at 22 September 2003, the grotto and associated stairs, balustrade and retaining walls are ornamental structures created between 1832 and 1835 to embellish the then 22-hectare (55-acre) garden of Elizabeth Bay House, built between 1835 and 1839 by Alexander Macleay (1767–1848), Colonial Secretary of New South Wales (1826–1837). They are surviving remnants of arguably the most sophisticated landscape design of the 1820s and 1830s in New South Wales, which adapted late 18th Century English Landscape and Picturesque Movement ideals (as interpreted by the early 19th century Gardenesque Movement) for the Sydney Harbour topography.[2]

The siting of Elizabeth Bay House and the layout of its drives, garden terraces and grottoes was carefully planned to maximise vistas and the dramatic Sydney Harbour topography. The design of the estate employed contrasts between the Greek Revival mansion (Elizabeth Bay House) and its formal placement within a broader Sydney Harbour landscape with the picturesque design and siting of outbuildings and garden structures. These included the demolished spired stables (c.1828, designer unknown), a gardener's cottage (1827), rustic bridge and pond (c.1832) and the extant grottoes, retaining walls and stairs. Architect, John Verge (1788–1862) is believed to have been responsible for the design of the grotto and retaining walls. The Elizabeth Bay estate inspired artistic responses to the landscape, particularly by painter, Conrad Martens (1801–1878).[2]

The Elizabeth Bay House garden terrace walls have local significance as they formed property boundaries following subdivision of 1882 and 1927. The grotto and rustic bridge became garden features of villas built following the 1882 subdivision.[2][24]

The grotto and retaining walls was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[2]

Gallery

Elizabeth Bay House, interior

Elizabeth Bay House, interior Elizabeth Bay House staircase, designed by John Verge

Elizabeth Bay House staircase, designed by John Verge Photograph from around 1927 of the staircase

Photograph from around 1927 of the staircase Alex Rigby's 21st Birthday Party in 1937

Alex Rigby's 21st Birthday Party in 1937

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 "Elizabeth Bay House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00006. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Elizabeth Bay House Grotto Site and works". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00116. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - 1 2 "Elizabeth Bay House (Place ID 2000)". Australian Heritage Database. Australian Government. 21 March 1978. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Perkins, Matthew (3 September 2010). "Colonial delusions of grandeur and our history". ABC News. Australia. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Carlin, S., 2000.

- 1 2 Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, 2000, p.38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hughes, 2002

- ↑ State Library, 2002.

- ↑ Plants received, c. 1826-1840, and Seeds received, 1836-1857

- ↑ Holliday, 2017.

- 1 2 Carlin/HHT, 2010, 13

- 1 2 Malone, Insites, Winter 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Sydney Living Museums, 2014.

- ↑ Morris, 1994

- ↑ Read, Stuart, pers.comm., based on "a walk around the estate", in Carlin, S., 2000

- ↑ Lucas & McGinness, 2012

- 1 2 Watts, 2014

- 1 2 Hunt, 1-3.

- ↑ "MTV Presents Summerbeatz 2010!". MTV Australia. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ↑ Historic Houses Trust, 1984.

- ↑ "Winter Solstice Sunrise at Elizabeth Bay House". Observations. Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, Government of New South Wales. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Historic Houses Trust. 1997.

- ↑ Hunt:1-2

- ↑ Historic Houses Trust, 2003.

Bibliography

- "Elizabeth Bay House Grotto Site and Works". 2007.

- Attraction Homepage (2007). "Historic Houses Trust Elizabeth Bay House Grotto Site and works".

- Carlin, Scott (2000). "Elizabeth Bay House - a history and guide".

- Carlin, Scott (assumed); Historic Houses Trust of NSW (2010). Refurbishing the Drawing Room of Elizabeth Bay House.

- Curran, Helen (2016). "A 'Botanist's Paradise' - Elizabeth Bay House".

- Carlin, Scott (1998). "draft Conservation Management Plan". Archived from the original on 9 January 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2006.

- Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales (2003). Elizabeth Bay House escarpment: nomination for the state heritage register [Variant additional information for the state heritage register].

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales (2004). "Museums".

- Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales (2006). "The Grotto & the Garden of Elizabeth Bay House".

- Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales (2007). "Elizabeth Bay House".

- Holliday, Steve (2017). "'Magnolia denudata - Yulan magnolia'".

- Hughes, Joy (2002). MacLeay, Alexander (and sons) entry in the 'Oxford Companion to Australian Gardens'.

- Lucas, Clive; McGinness, Mark (2012). 'John Fisher - 1924-2012 - champion of the state's structures'.

- Malone, Gareth (2008). Winter solstice at Elizabeth Bay House.

- Mayne Wilson & Associates (2001). Heritage study and review of proposed landscape master plan of the McElhone Reserve, Elizabeth Bay, NSW.

- Morris, Colleen (1994). Through English Eyes, extracts from the journal of John Gould Veitch during a trip to the Australian colonies.

- Morris, Colleen (2008). Morris, Colleen. Lost gardens of Sydney. Produced in association with an exhibition at the Museum of Sydney 9 August - 30 November 2008.

- State Library of NSW (2002). Villas of Darlinghurst (exhibition catalogue), entry on Elizabeth Bay House.

- Sydney Living Museums (2014). 'Ten things you might not have known about Elizabeth Bay House', in 'Eastern Suburbs Insider'.

- Watts, Peter (2014). (Open) Letter to Tim Duddy, Chairman, Friends of the Historic Houses Trust Inc.

Attribution

This Wikipedia article contains material from Elizabeth Bay House, entry number 6 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from Elizabeth Bay House, entry number 6 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from Elizabeth Bay House Grotto Site and works, entry number 116 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from Elizabeth Bay House Grotto Site and works, entry number 116 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

Further reading

- Broadbent, J. The Australian colonial house : architecture and society in New South Wales 1788-1842. Sydney, Hordern House in Assoc. with the Historic Houses Trust of NSW. 1997

- The Book of Sydney Suburbs, Compiled by Frances Pollen, Angus & Robertson Publishers, 1990, Published in Australia ISBN 0-207-14495-8