The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana is a special collection at the University of California, Los Angeles which focuses on Leonardo da Vinci – life, art, thought, and enduring cultural influence. It is the most extensive research collection concerning Leonardo in the United States.[1] It was donated to UCLA in several installments between 1961 and 1966 by Dr. Elmer Belt (1893-1980),[2] an internationally recognized urologist; a pioneer in gender-affirming surgery; a strong supporter in the founding of the UCLA School of Medicine;[3] an important public health advocate; and a lifelong bibliophile and book collector.[4]

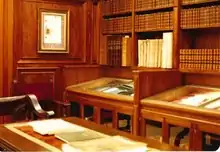

The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana was officially dedicated in 1966 when UCLA opened in its Dickson Art Center a suite of wood-paneled and antique-filled rooms especially designed to house Belt’s collection. However, in 2002, the Dickson Art Center was transformed into the Broad Art Center, and the Belt Library was removed from its quarters and ultimately its holdings were integrated into UCLA Library Special Collections.[5]

Development of the collection

Dr. Belt’s fascination with Leonardo was kindled while he was in medical school (1917–20) at the University of California, San Francisco, where he took an elective class in the history of medicine from the noted anatomist, George W. Corner. During the class, Corner introduced him to Leonardo. Captivated by Leonardo’s anatomical studies, Belt purchased a 1901 facsimile edition of Anatomical Manuscript B published by Teodoro Sabachnikoff, his first item of Vinciana. Some years later Belt finally tracked down the companion volume, Dell’Anatomia, Fogli A, published in 1898. By then he had begun to formulate his ambition to assemble the world’s best and most complete collection devoted to Leonardo.[6]

Belt did not labor alone. Two remarkable collaborators worked alongside him. One was Jake Zeitlin (1902-1987), dean of California antiquarian booksellers. Around 1928, Belt recruited Zeitlin to acquire two copies of Ettore Verga’s Bibliografia Vinciana 1493-1930, a monumental two-volume bibliography of all books by and about Leonardo published in 1931, saying, “I will keep one and you keep one, and I want you to get me every book in there.”[7]

Belt’s second partner, Kate Steinitz (1889-1975) was equally instrumental in building the Belt collection.[8] Steinitz, a refugee from Nazism, emigrated to America in the thirties. An accomplished artist, intimately acquainted with the European avant-garde (including Kurt Schwitters, to whom she devoted an important study), Steinitz also maintained a lively interest in the history of art. Arriving in New York in 1936 and learning that Zeitlin was anxious to purchase Leonardo materials, she volunteered to scout for him.[8] She quickly impressed Zeitlin with her first major find: a copy of Luca Pacioli's Divina proportione of 1509.[8] From that point forward, Steinitz proved indispensable. In 1945 she was hired as Belt's personal librarian, and she ultimately became a widely esteemed Leonardo scholar. Her bibliography of Leonardo's Treatise on Painting remains unsurpassed, and she made the Belt Library a center of the far-flung world of international Leonardo scholarship. In 1969 the city of Vinci formally recognized Steinitz's contributions, inviting her to deliver the annual Lettura Vinciana.[8]

Until the collection’s transfer to UCLA beginning in 1961, it was housed at 1893 Wilshire Boulevard in downtown Los Angeles on the second floor of the office building that Belt had purchased for his medical practice, the Belt Urologic Group.[9]

Collection overview and highlights

%252C_ca._1590.jpg.webp)

Dr. Belt's Leonardo da Vinci collection was his major undertaking as a collector. He aimed to build the most extensive collection on Leonardo in the world by acquiring (1) all editions of Leonardo’s works in facsimile; (2) all published works known to have been consulted by Leonardo in the editions the artist used (“Leonardo’s Library”); (3) many early-printed books important to the history of art, beginning with Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists; and (4) modern scholarly literature on Leonardo and his legacy in the arts and sciences.[10] He also ultimately acquired all printed editions of Leonardo’s Treatise on Painting plus two important manuscript versions of the Treatise that preceded the first printed edition; and a collection of Leonardo-related graphic arts materials, such as prints after the artist’s so-called "grotesques."[11][12]

The Belt Library contains 60 incunabula.[13] It also contains many fifteenth- and sixteenth-century architectural treatises, from Leon Battista Alberti's De re aedificatoria of 1485 to the treatises of Sebastiano Serlio, Andrea Palladio, Gian Paolo Lomazzo, Vincenzo Scamozzi, and Vignola. It also contains a comprehensive collection of early art treatises and biographical works (e.g., those by Giorgio Vasari, Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Filippo Baldinucci, and Giovanni Battista Passeri.) In addition, there are treatises on perspective, studies of human and animal anatomy, and works on engineering, warfare, and mathematics. Among its other notable holdings are an exceptionally fine copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493); the first book containing a printed mention of Leonardo, Bernardo Bellincioni's Rime (1493); and a first edition of Andreas Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica (1543).[14]

Several of the Belt Library's rare books are particularly remarkable for their provenances.[14] Franchino Gaffurio, choirmaster of Milan Cathedral and author of two seminal musical treatises, penned an ownership inscription in the Belt copy of Plutarch's Vitae (Guinta, 1491). Especially important from an art historical point of view is a copy of Francesco Scannelli's Microcosmo della Pittura (1657), owned and annotated in succession by painter Francesco Albani, a major representative of the Carracci school; and Francesco Gabburri, a diplomat, painter, art collector, and biographer of artists. In volume two of his Felsina Pittrice of 1678, Carlo Cesare Malvasia, in his biography of Albani, quotes extensively from Albani's marginalia. The Belt Library also holds Edward Burne-Jones's interleaved copy of Vasari's Lives of the Artists in the English translation of Mrs. Jonathan Foster.[15]

The Belt Library contains as well several notable manuscripts. A brief document by Michelangelo describes a meeting with Pope Clement VII at San Miniato al Tedesco in 1533, mentioning that the artist was at the time caring for a horse belonging to his friend the painter Sebastiano del Piombo. Especially important is a notarial document on vellum in the hand of Leonardo's father, Ser Piero da Vinci. Dated 8 November 1458, this document is the contract for the sale of a house and properties outside Florence. One of the finest pieces in the library is an illuminated initial leaf from a copy of printer Nicholas Jenson’s 1476 edition of Pliny’s Naturalis historia. The striking border decoration is attributed by Wilhelm Suida to the miniaturist Cristoforo de Predis, active in Milan circa 1471-86.[16] (Cristoforo's brothers Ambrogio and Evangelista were Leonardo's business partners during his prolonged sojourn in Milan at the end of the fifteenth century.) Perhaps the loveliest piece in the Belt Library is a pencil study by Edgar Degas, after Leonardo's Uffizi Adoration of the Magi in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. The sketch is inscribed in the upper right-hand corner “Florence 1869. Leonard de Vinci” and in the lower left-hand corner is the red stamp “Degas” from the Durand-Ruel inventory created after Degas’ death.[17]

Carlo Pedretti (1928-2018) and the Belt Library

In the late 1950s, Kate Steinitz learned through her friends in Europe of a young Leonardo scholar named Carlo Pedretti, who had published his first article on Leonardo at the age of 16 and who had established himself as a leading authority in his field by the age of 20. Steinitz and Belt arranged to bring Carlo Pedretti to California; he joined the faculty of UCLA’s Art History Department in 1960. He served in this position for 38 years, during which time his scholarship and teaching animated the Belt Library and raised its profile in the international academic community. A highly productive scholar, Pedretti published 60 books and more than 500 essays, articles, and exhibition catalogues. From 1988-97, he was the editor of Achademia Leonardi Vinci: Journal of Leonardo Studies and Bibliography of Vinciana.[18]

Additional gifts to the Belt Library of Vinciana

During the Belt Library’s early years at UCLA, the collection was augmented with donations of rare materials from scholars Lynn White Jr. (a UCLA historian specializing in medieval technology and social change); Ladislao Reti (an Italian scholar and friend of Pedretti’s who was an authority on the technological work of Leonardo); and Bern Dibner (an American rare book collector and historian of science and technology).[19]

Belt librarians during the UCLA years

Frances L. Finger was Belt Librarian from sometime in the 1960s until her death in 1975. During her tenure, she researched and published Catalogue of the Incunabula in the Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana, a work of impressive scholarship that traces the relevance of the Library’s fifteenth-century books to the study of Leonardo.[20]

Victoria Steele led the Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana from 1975-1981. During her tenure, she published “The First Italian Printing of Leonardo da Vinci’s Treatise on Painting”;[21] and for an exhibition focused on Belt Library holdings mounted by the University of Southern California, she published The Heritage of Leonardo da Vinci: Materials from the Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana at the University of Southern California Art Galleries[22] and made the presentation, "The Elmer Belt Library at UCLA: The Collector, the Curator, and Leonardo da Vinci."[23][24][25]

Max Marmor was Belt Librarian from 1982-88. During his tenure, he published “In Obscure Rebellion: The Collector Elmer Belt” [26] and a history and overview of the Belt Library, “The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana,” in The Book Collector.[27]

The Belt Library's integration into UCLA Library Special Collections

Dr. Franklin Murphy, UCLA Chancellor from 1961–68, encouraged and supported Dr. Belt’s donation of his collection to UCLA, and Murphy directed that an elegant suite be specially created for it within the Art Library in UCLA’s Dickson Art Center. The suite consisted of two wood-paneled rooms, furnished with Renaissance furniture, antiques, artwork, and art objects, some of which were donated by the Kress Foundation and others of which were donated by collector and industrialist Norton Simon.[28]

Though Belt desired an institutional home for his collection, he worried, during the planning phase of his donation to UCLA, that at some point in the future his library might be integrated into the university library’s overall collection. In a letter dated June 29, 1961, Murphy wrote to Dr. Belt to dispel the “notion that we would propose to integrate your library into our total library holdings in such a way that your library might lose its identification. I therefore hasten to make one thing crystal clear. It is the firm and unalterable intention of all of us that this library will be known in perpetuity as the Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana.”[28]

In 2000, Eli and Edythe Broad, prominent Los Angeles philanthropists and art collectors, donated $23.2 million to UCLA in order to revamp Dickson Art Center and convert it into an on-campus center for studio art.[29] They aimed to provide improved facilities for interactive multimedia, expanded studio space, updated classrooms, and galleries for student exhibitions and public presentations. Then-UCLA Executive Vice Chancellor Daniel Neuman decided that Dickson Art Center should no longer house the Art Library, including the Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana. As a result, the Art Library was relocated to a space in the Meyer & Renee Luskin Public Affairs building that had formerly housed the business school’s library. However, the square footage of the new space was smaller by almost exactly the square footage needed to accommodate the Belt Library. In the absence of a solution to this problem, the University sent the Belt Library’s furniture and antiques to off-site storage.[5] The books and manuscripts were transferred to Library Special Collections, where former Belt Librarian Victoria Steele was serving as director.[30] She ensured that the Belt Library’s rarities were shelved as a distinct collection within its rare book stacks. Reference items and some other secondary materials were eventually relocated to the Southern Regional Library Facility (SRLF) on the UCLA campus.[30]

The collection remains accessible through Library Special Collections, although it is no longer possible to cross-consult multiple sources.[31]

Printed sources

Marmor, Max. "The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana." The Book Collector 38, no. 3 (Autumn 1989): 1-23.

Pedretti, Carlo. Leonardo da Vinci: Studies for a Nativity and the 'Mona Lisa Cartoon' with Drawings after Leonardo from the Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana: Exhibition in Honour of Elmer Belt, M.D. on the Occasion of his Eightieth Birthday. Los Angeles: University of California, 1973.

Surgeon and Bibliophile: Elmer Belt. Oral History Transcript; interviewed by Esther de Vécsey between 1974-75. Los Angeles: Oral History Program, University of California, Los Angeles, 1983.

Digital sources

- The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana Internet Archive.

- Elmer Belt collection of Vinciana graphic arts. Online Archive of California.

- UCLA Arts Library: The Belt. Art Library Crawl.

Archival sources

- Elmer Belt Papers 1920-1980, bulk 1958-1978. Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections for the Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles. Opened for research 2020.

- Note: the papers contain very little prior to 1958. In that year, a fire in Belt's medical offices seem destroyed almost everything dated earlier than 1958. in addition, access is restricted for some materials owing to patient or legal confidentiality protocols.

References

- ↑ The Heritage of Leonardo da Vinci: Materials from the Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana, University of California, Los Angeles. University Art Galleries, University of Southern California. 1982. pp. v.

- ↑ Dibner, Birn. “Elmer Belt (1893-1980).” Technology and Culture 22, no. 4 (1981): 837–38.

- ↑ Arthur, Ransom (1992). By the Old Pacific's Rolling Water: Birth of the UCLA School of Medicine. Los Angeles: UCLA School of Medicine. p. 63.

- ↑ Finger, Frances (1971). Catalogue of the Incunabula in the Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana. Friends of the UCLA Library. pp. v.

- 1 2 "Finding Aid for the Library. University Librarian. Administrative files of Gloria Werner. c.1985-2003. Box 8". Archived from the original on 2021-08-20.

- ↑ Marmor, Max (1989). "The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana". The Book Collector. 38 (3): 3.

- ↑ Books and the Imaginiation: Fifty Years of Rare Books: Jake Zeitlin. Los Angeles: UCLA Oral History Program. 1980. p. 291.

- 1 2 3 4 Marmor, Max (1989). "The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana". The Book Collector. 38: 11.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin (1990). Material Dreams: Southern California Through the 1920s. Oxford University Press. p. 332.

- ↑ Marmor, Max (1989). "The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana". The Book Collector. 38: 11–12.

- ↑ Steinitz, Kate (1958). Leonardo da Vinci's Trattato della Pittura. Munksgaard. p. 12.

- ↑ "Belt (Elmer) Collection of Vinciana Graphic Arts".

- ↑ Finger, Frances (1971). Catalogue of the Incunabula in the Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana. Friends of the UCLA Library.

- 1 2 Marmor, Max (1989). "The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana". The Book Collector. 38: 20.

- ↑ Marmor, Max (1989). "The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana". The Book Collector. 38: 20–21.

- ↑ Suida, Wilhelm (1947). "Italian Miniature Paintings from the Rodolphe Kann Collection". Art in America. 35: 19–33.

- ↑ Marmor, Max (1989). "The Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana". The Book Collector. 38: 22–23.

- ↑ Kendall, Rebecca (January 18, 2018). "In memoriam: Carlo Pedretti, 89, art historian and da Vinci scholar". UCLA Newsroom.

- ↑ "Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana". Archived from the original on 2017-09-21.

- ↑ Seldis, Henry (1 May 1966). "Symposium Will Salute Library of Elmer Belt". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 155447531.

- ↑ Steele, Victoria. 1980. "The First Italian Printing of Leonardo Da Vinci's Treatise on Painting 1723 or 1733?" Notiziario Vinciano. 3-24

- ↑ University of Southern California. The Heritage of Leonardo Da Vinci: A Special Exhibition at the University of Southern California Art Galleries Exhibited in Conjunction with Leonardo's Return to Vinci: The Countess of Béhague Collection. Los Angeles: University Art Galleries, University of Southern California, 1982.

- ↑ "Los Angeles Institute for the Humanities Fellow Roster". Los Angeles Institute for the Humanities. Archived from the original on 2014-08-27.

- ↑ Steele, Victoria,"Exposing hidden collections:The UCLA experience College & Research Library News 69, No 6 (June, 2008):316-3-17; 331.

- ↑ Steele, Victoria (2016)"The Elmer Belt Library at UCLA: The Collector, the Curator, and Leonardo da Vinci"UCLA Library.

- ↑ Marmor, Max C. “In Obscure Rebellion: The Collector Elmer Belt.” The Journal of Library History (1974) 22, no. 4 (1987): 409–24.

- ↑ "Kress Foundation". Kress Foundation. Archived from the original on 2021-01-18.

- 1 2 Letter from Chancellor Franklin D. Murphy to Elmer Belt dated June 29, 1971, in the Elmer Belt Papers, unprocessed collection, UCLA Library Special Collections.

- ↑ Timberg, Scott (14 September 2006). "UCLA Celebrates Its New Art Center; Eli and Edythe Broad donated almost half of the $52-million cost for the teaching, work and exhibition spaces". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 422052425.

- 1 2 Director's files, "Belt Library," UCLA Library Special Collections

- ↑ Elmer Belt Library of Vinciana