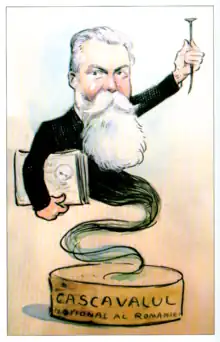

Emil Costinescu (March 12, 1844–July 6, 1921) was a Romanian economist, businessman and politician.

Born in Iași, Costinescu was the self-taught son of the architect and engineer Alexandru Costinescu, professor at the Academia Mihăileană and later the director of the School of Bridges and Roads, Mines and Architecture in Bucharest. He was influenced by the reformist ideals of the time in which he was growing up, as expounded by figures such as C. A. Rosetti, Cezar Bolliac and Mihail Kogălniceanu. In 1862, he was hired as proofreader at Rosetti's Românul. He advanced to editor in 1866 and led the newspaper during the founder's exile.[1] A member of the National Liberal Party,[2] he was first elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1876,[1] and in 1880 was a co-founder of the National Bank of Romania.[1][2] In 1897, he became the founding president of the General Bank of Bucharest, one of the country's largest.[2][3][4] He opened a sawmill in Sinaia, and sat on the board of a petroleum company.[4]

Costinescu was Finance Minister three times: July 1902-December 1904, March 1907-December 1910 and January 1914-December 1916.[3] An economic protectionist, he supported a customs tariff in the belief that it would spur the development of domestic industry. Introduced in 1904, this measure lasted until 1924. Also, as early as 1887, he spoke in favor of an income tax. In late 1909, he introduced a bill in parliament that would have established such a tax; the proposal failed.[1] At the end of his third term, in the midst of World War I, he was involved in the decision to send the Romanian Treasure to Russia for safekeeping.[5] Costinescu remained in the wartime government as Minister without portfolio from December 1916 to July 1917.[3] After the war, he took part in the Romanian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference as a financial expert.[2]

The Black Sea resort of Costinești is named after Costinescu, who purchased a 200-hectare estate from Vasile Kogălniceanu. He found an arid, treeless landscape, inviting German colonists to settle and work the land.[6]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Ionel Maftei, Personalități ieșene, vol. II, pp. 97-8. Iași: Comitetul de cultură și educație socialistă al județului Iași, 1972

- 1 2 3 4 Wojciech Roszkowski and Jan Kofman, Biographical Dictionary of Central and Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century, pp. 1925-26. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis, 2016, ISBN 978-13174-7593-4

- 1 2 3 Sabina Cantacuzino (ed. Elisabeta Simion), Din viața familiei Ion C. Brătianu, vol. II, p. 314. Bucharest: Editura Albatros, 1996

- 1 2 Dimitrie Rosetti, Dicționarul Contimporanilor, p. 57. Editura Lito-Tipografiei "Populara", Bucharest, 1897

- ↑ (in Romanian) Dan Falcan, “Bancherul Mauriciu Blank și tezaurul României”, in Historia, December 2016

- ↑ Gheorghe Andronic, Litoralul românesc al Mării Negre, p. 88. Bucharest: Editura Sport-Turism, 1989