| Eritrean–Ethiopian border conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eritrean–Ethiopian War | |||||||||

Territory claimed by both sides of the conflict | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Rebel allies TPDM EPPF |

Rebel allies DFEU ENSF Supported by (Eritrean claim)[1] | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Unknown rebels |

(1998–2000) Unknown rebels | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

650,000 civilians displaced Total ~100,000 killed | |||||||||

The Eritrean–Ethiopian border conflict was a violent standoff and a proxy conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia lasting from 1998 to 2018. It consisted of a series of incidents along the then-disputed border; including the Eritrean–Ethiopian War of 1998–2000 and the subsequent Second Afar insurgency.[8] It included multiple clashes with numerous casualties, including the Battle of Tsorona in 2016. Ethiopia stated in 2018 that it would cede Badme to Eritrea. This led to the Eritrea–Ethiopia summit on 9 July 2018, where an agreement was signed which demarcated the border and agreed a resumption of diplomatic relations.[9][10]

Background

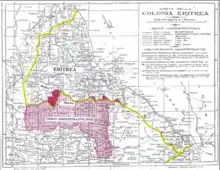

Colonisation and border conflict

In March 1870, an Italian shipping company became a claimant to the territory at the northern end of Assab Bay, a deserted but spacious bay about half-way between Annesley Bay to the north and Obock to the south.[11] The area —which had long been dominated by the Ottoman Empire and Egypt was not settled by the Italians until 1880.[12] In 1884, the Hewett Treaty was signed between the British Empire and Ethiopia, reigned by Emperor Yohannes IV (r. 1871–1889). The British Empire promised the highlands of modern Eritrea—and free access to the Massawan coast to Ethiopia in exchange for its help evacuating garrisons from the Sudan, in the then-ongoing Mahdist War.[13] In 1889, the disorder that followed the death of Yohannes IV, Italian General Oreste Baratieri occupied the highlands along the Eritrean coast and Italy proclaimed the establishment of a new colony of "Eritrea", (from the Latin name for the Red Sea), with its capital at Asmara in substitution for Massawa.[14] On 2 May 1889, the peace and friendship Treaty of Wuchale was signed between Italy and Ethiopia, under which Italian Eritrea was officially recognised by Ethiopia as part of Italy.[15] However, Article 17 of the treaty was disputed, as the Italian version stated that Ethiopia was obliged to conduct all foreign affairs through Italian authorities (in effect making Ethiopia an Italian protectorate), while the Amharic version gave Ethiopia considerable autonomy, with the option of communicating with third powers through the Italians.[16][17][18] This resulted in the First Italo-Ethiopian War,[19] which the Ethiopians won, resulting in the Treaty of Addis Ababa in October 1896. Italy paid reparations of ten million Italian lira. Unusually, the Italians retained most, if not all, of the territories beyond the Mareb-Belessa and May/Muni rivers that they had taken, with Emperor Menelik II (r. 1889–1913) giving away part of Tigray.[20][21] On 2 August 1928, Ethiopia and Italy signed a new friendship treaty.[22]

Ethiopia under Italian rule

On 22 November 1934, Italy claimed that three senior Ethiopian military-political commanders with a force of 1,000 Ethiopian militia arrived near Walwal and formally requested the garrison stationed there, comprising about 60 Somali soldiers, known as dubats, to withdraw.[23] The Somali NCO leading the garrison refused and alerted Captain Cimmaruta, commander of the garrison of Uarder, 20 kilometres (12 mi) away, what had happened.[24] Between 5 and 7 December 1934, for reasons which have never been clearly determined, a skirmish broke out between the garrison and the Ethiopian militia. According to the Italians, the Ethiopians attacked the Somalis with rifle and machine-gun fire.[25] According to the Ethiopians, the Italians attacked them, supported by two tanks and three aircraft.[26] According to historian Anthony Mockler 107 Ethiopians were killed.[27] By 3 October 1935, the Italian Army led by General Emilio De Bono launched an invasion of Ethiopia, without a declaration of war. This was the start of a new war called the Second Italo-Ethiopian War.[28] In May 1936, the Italian Army occupied the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa.[29] The occupied country was annexed into the Italian East African colony together with the other Italian east African colonies.[30]

On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on Britain and France;[31] in March 1941, Britain began a campaign to capture the Italian-held territory in the region.[32] By November, the British had occupied the whole Italian East African colony. However thousands of Italian soldiers began conducting a guerrilla war within their former colony[33] which lasted until October 1943.[34] After the end of WWII, Ethiopia regained her independence, and Eritrea was placed under Britain military administration.[35]

Prelude

Eritrea as part of Ethiopia

After the war there was a debate as to what would happen to Eritrea. After the Italian communists' victory in the 1946 Italian general election they supported returning Eritrea to Italy under a trusteeship or as a colony. The Soviet Union similarly wished to make it their trustee; and tried to achieve this by diplomatic means, but they failed.[36][37]

Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I (r. 1930–1974) also claimed Eritrea. In 1952 the United Nations decided that Eritrea would become part of the Ethiopian Empire. Eritrea became a special autonomous region within a federated Ethiopia.[38]

In 1958, a group of Eritreans founded the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF). The organisation mainly consisted of Eritrean students, professionals and intellectuals. It engaged in clandestine political activities intended to cultivate resistance to the centralising policies of the imperial Ethiopian state.[39] During the following decade the Emperor decided to dissolve the federation between Ethiopia and Eritrea, annexing the special region and bringing it under direct rule.[38]

This resulted in an almost thirty-year long armed struggle known as the Eritrean War of Independence.[40][38] The ELF engaged in armed conflict against the Ethiopian Government from 1 September 1961. In 1970 a group called the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) broke off from the ELF.[41] They were fierce rivals and in February 1972, the First Eritrean Civil War broke out between them.[42] Their rivalry paused in 1974, and calls for the conflict to stop were finally heeded. These calls for peace came from local villagers at a time when the independence movement was close to victory over Ethiopia.[42] On 12 September 1974, a successful coup d'état was carried out against the Emperor led by Lieutenant General Aman Andom. The government was led by members of the pro-Soviet Ethiopian military, which established an almost seven-year long military junta.

The ELF-EPLF's peace lasted only six years; in February 1980 the EPLF declared war on the ELF, after which the ELF and the Soviet Union started secret negotiations. The Second Eritrean Civil War lasted until 1981, and the EPLF emerged victorious. The ELF was driven out of Eritrea into Sudan. On 27 May 1991 the new Ethiopian Transitional Government was formed after the fall of the pro-Soviet government. The Ethiopian Transitional Government promised to hold a referendum, within two years in the region. The referendum was held between 23 and 25 April 1993 with 99.81% voting in favour of independence. On 4 May 1993 the official independence of Eritrea was established.[43] However, the border between Ethiopia and newly independent Eritrea was not clearly defined. After border skirmishes in late 1997, the two countries attempted to negotiate their boundary.[44] In October 1997, Ethiopia presented the Eritrean Government a map showing Eritrean-claimed areas as part of Ethiopia.[45]

History

Major combat phase (1998–2000)

On 6 May 1998, border clashes erupted between Ethiopia and Eritrea, killing several Eritrean civilians in the Eritrea town of Badme.[46][47] Ethiopian soldiers attacked Eritrean civilians and Eritreans soldiers retaliated.[46][48][note 1]

On 13 May 1998, the Ethiopian government mobilised their army for a full assault against Eritrea through the town of Badme. Badme has historically been the home of Eritreans and the people who live in Badme are citizens of Eritrea and who pay their taxes to the Eritrean Government. Aside from Badme, Ethiopia had also mobilized her troupes in several places along the Eritrean border with the aim launching a full-scale invasion of Eritrea. Eritrea retaliated by air and ground successfully defending and securing her borders and defeating the Ethiopian military within days. The Eritrean government asked the Ethiopian military to pull back, but the Ethiopians continued their attacks. When Ethiopians could not penetrate Eritrea's borders, Ethiopia sought out assistance from the United States claiming that the Eritreans were the aggressors. The United States didn't physically interfere but supplied Ethiopia weapons and gave them tactical intelligence reports. Ethiopia went to the UN falsely claiming Eritrean aggression on their land. The United Nations investigation showed that Ethiopia had actually illegally aggressed on Eritrean territory. Ethiopia continued her attacks on Eritrea until they were defeated for good by EPLF (Eritrean People Liberation Front) in May 2000. After this defeat, Ethiopia agreed to enter into peace talks with Eritrea still trying to claim Eritrean land as their territory. The Tigryan led Ethiopian government walked out of many peace talks arranged in Algeria. The United Nations, mediators and several other world organizations sided with Eritrea and let Ethiopia know that if they cross the Eritrean borders again, it will be an act of war and that Eritrea has the right to retaliate. Unable to defeat Eritrea in war and through political means the UN or The Claims Commission (established by the Algiers peace agreement), Ethiopia finally ended her military aggression on Eritrea and began a 20 year long cold war with Eritrea.

Post-war conflict on the border (2000–2018)

After a cease-fire was established on 18 June 2000, both parties agreed to have a 25-kilometre-wide (16 mi) demilitarised zone called the Temporary Security Zone (TSZ). It was patrolled by the United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE) an organisation for the border stabilisation and the prevention of future conflicts between the countries. On 31 July 2000, the UNMEE was officially launched and started patrolling the border.[50] On 12 December 2000, a peace agreement was signed in Algiers.[51] In August 2002 Eritrea released all the Ethiopian POWs.[52]

Both countries vowed to accept the decision wholeheartedly the day after the ruling was made official.[53] A few months later Ethiopia requested clarifications, then stated it was deeply dissatisfied with the ruling.[54][55][56] In September 2003 Eritrea refused to agree to a new commission,[57] which they would have had to agree to if the old binding agreement was to be set aside,[58] and asked the international community to put pressure on Ethiopia to accept the ruling.[57] In November 2004, Ethiopia accepted the ruling "in principle".[59]

2005–2006

On 10 December 2005, Ethiopia announced it was withdrawing some of its forces from the Eritrean border "in the interests of peace".[60] Then, on 15 December the United Nations began to withdraw peacekeepers from Eritrea in response to a UN resolution passed the previous day.[61]

On 21 December 2005, a commission at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled that Eritrea broke international law when it attacked Ethiopia in 1998, triggering the broader conflict.[62]

Ethiopia and Eritrea subsequently remobilized troops along the border, leading to fears that the two countries could return to war.[63][64] On 7 December 2005, Eritrea banned UN helicopter flights and ordered Western members (particularly from the United States, Canada, Europe and Russia) of the UN peacekeeping mission on its border with Ethiopia to leave within 10 days, sparking concerns of further conflict with its neighbour.[65] In November 2006 Ethiopia and Eritrea boycotted an Eritrea–Ethiopia Boundary Commission meeting at The Hague which would have demarcated their disputed border using UN maps. Ethiopia was not there because it does not accept the decision and as it will not allow physical demarcation it will not accept map demarcation, and Eritrea was not there because although it backs the commission's proposals, it insists that the border should be physically marked out.[66]

2007–2011

In September 2007, Kjell Bondevik, a United Nations' official, warned that the border conflict could cause a new war.[67] At the November 2007 deadline, some analysts feared the restart of the border war but the date passed without any conflict.[68] There were many reasons why war did not resume. Former U.S. Ambassador David Shinn said both Ethiopia and Eritrea were in a bad position. Many feared the weak Eritrean economy is not improving like those of other African nations, while others say Ethiopia was still bogged down in its intervention in Somalia. David Shinn said Ethiopia has "a very powerful and so far disciplined national army that made pretty short work of the Eritreans in 2000 and the Eritreans have not forgotten that."[68] But he stated Ethiopia is not interested in war because America would condemn Ethiopia if it initiated the war saying "I don't think even the US could sit by and condone an Ethiopian initiated attack on Eritrea."[68]

On 16 January 2008, the Eritrean Government said they gave up all of its claims in Ethiopia.[69] In February, the UNMEE commenced pulling its peacekeepers out of Eritrea due to Eritrean Government restrictions on its fuel supplies.[67] On 30 July 2008, the Security Council held a vote which ended the UN mission the next day.[70] In June 2009 a rebel group called Democratic Movement for the Liberation of the Eritrean Kunama (DMLEK) joined the fight against the Eritrean Government with the pro-Ethiopian Red Sea Afar Democratic Organisation (RSADO).[3] On 23 April 2010, RSADO and the Eritrean National Salvation Front (ENSF) attacked an Eritrean Army's base, they also took it over for 3 hours until 6 a.m. They killed At least 11 Eritreans soldiers and wounded more than 20 others.[71]

2012–2018

The conflict deepened in March 2012, when Ethiopia launched an offensive into Eritrean-held territory. Three Eritrean military camps were attacked, and a number of people were killed or captured.[67][72] Several weeks prior to the offensive, Ethiopia blamed Eritrea for supporting the Ethiopian rebels who had staged the Afar region tourist attack in northern Eithiopia, in which five Western tourists were killed.[67] On 7 September 2013, two Ethiopian-supported Eritrean rebel groups RSADO and the Saho People's Democratic Movement (SPDM) agreed to fight together against the Eritrean Government.[73] In December 2013 the Ethiopian Army, crossed the border to attack some rebel camps in Eritrea.[74]

In June 2016, Eritrea claimed that 200 Ethiopian soldiers were killed and 300 wounded in a battle at Tsorona.[40] On 22 June 2016 Eritrea warned the UN Human Rights Council that a new war between Ethiopia and the country can restart as Ethiopia was planning for a new attack.[74]

2018 Eritrea–Ethiopia summit

On 2 April 2018, former Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn resigned due to the unrest and a new Ethiopian Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, was appointed.[75] On 5 June 2018 Ahmed announced that Ethiopia relinquished its claims on the disputed areas and that the conflict with Eritrea was at an end.[76] He arrived on 8 July 2018 in Asmara, Eritrea. Where his counterpart, President Isaias Afwerki, greeted him at Asmara International Airport.[77] The next day both leaders signed a five-point Joint Declaration of Peace and Friendship, which declared that "the state of war between Ethiopia and Eritrea has come to an end; a new era of peace and friendship has been opened" and ceded Badme to Eritrea.[78]

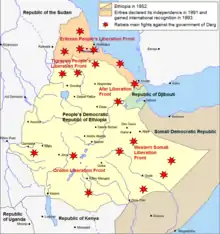

Proxy conflict

Since the cease-fire was established, both nations have been accused of supporting dissidents and armed opposition groups against each other. John Young, a Canadian analyst and researcher for IRIN, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs news agency, reported that "the military victory of the EPRDF (Ethiopia) that ended the Ethiopia–Eritrea War, and its occupation of a swath of Eritrean territory, brought yet another change to the configuration of armed groups in the borderlands between Ethiopia and Eritrea. Asmara replaced Khartoum as the leading supporter of anti-EPRDF armed groups operating along the frontier".[79] However, Ethiopia is also accused of supporting rebels opposed to the Eritrean government.[80][81]

In 2006 the Ethiopian Government deployed its forces in its neighbour country Somalia, backing the government by fighting against the Islamists. The Ethiopian and Somali governments, accuses Eritrea for backing the Islamists in the region, in reaction of the Somali Government it started backing the Eritrean rebels.[82] In April 2007 Ethiopia accuses also Eritrea for supporting the rebel groups like the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) and the Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Front (ARDUF). In April 2011 Ethiopia openly declared its support for Eritrean rebel groups.[67] According to the Global Security in 2014 the rebel group Tigray People's Democratic Movement (TPDM) which is active in the Tigray Region was the most important rebel group in Eritrea fighting against the Ethiopian Government, Eritrea also financed and train the group.[83]

In January 2015, the pro-Eritrean rebel groups, the Ginbot 7 and the Ethiopian People's Patriotic Front (EPPF) merged to fight against the Ethiopian Government, and called itself the Arbegnoch – Ginbot 7 for Unity and Democracy Movement (AGUDM).[84] On 25 July 2015, Ginbot 7 decided to go in an armed resistance and goes into exile in Eritrea.[85] On 10 October 2016, the Ethiopian Government claimed that Eritrea (was also helping Oromo Liberation Front [OLF])[86] and Egypt were behind the Oromo protests in Ethiopia.[87]

Impact and aftermath

Soon after the peace summit, many Ethiopian rebels returned to Ethiopia, including TPDM, OLF and Ginbot 7. On 10 October, the last 2,000 of TPDM members returned to Ethiopia.[88] The UN lifted its sanctions on 14 November 2018 after nine years against Eritrea. Eritrea made also a joint agreement with Somalia and Ethiopia to co-operate with each other.[89] Later on 13 December 2018 President Afwerki went to Somalia for the first time in two decades.[90]

During only the war, between 70,000 and 300,000 people were killed and 650,000 displaced,[40][91][92] of whom 19,000–150,000 were Eritrean soldiers[93] and 80,000–123,000 were Ethiopian soldiers.[94] The casualties after the war there were between 523 and 530 dead in the Second Afar insurgency alone. On the Eritrean side the casualties of the conflict were between 427 and 434 Eritreans killed, 30 pro-Eritrean rebels killed, 88 Eritrean soldiers wounded and 2 Eritreans captured. The Ethiopian side were 49 Ethiopian soldiers (claimed by rebels), and five civilians were killed, also, 23 civilians were kidnapped and three others were wounded.[95][96][97][71][98][99][100][101][102][103][104] On the both countries border, the casualties of both countries were according to Eritrea at least 18 Eritreans and over 200 Ethiopians.[105]

Timeline

On 19 June 2008 the BBC published a time line (which they update periodically) of the conflict and reported that the "Border dispute rumbles on":

* 2007 September – War could resume between Ethiopia and Eritrea over their border conflict, warns United Nations special envoy to the Horn of Africa, Kjell Magne Bondevik.

- 2007 November – Eritrea accepts border line demarcated by international boundary commission. Ethiopia rejects it.

- 2008 January – UN extends mandate of peacekeepers on Ethiopia–Eritrea border for six months. UN Security Council demands Eritrea lift fuel restrictions imposed on UN peacekeepers at the Eritrea–Ethiopia border area. Eritrea declines, saying troops must leave border.

- 2008 February – UN begins pulling 1,700-strong peacekeeper force out due to lack of fuel supplies following Eritrean government restrictions.

- 2008 April – UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon warns of likelihood of new war between Ethiopia and Eritrea if peacekeeping mission withdraws completely. Outlines options for the future of the UN mission in the two countries.

- Djibouti accuses Eritrean troops of digging trenches at disputed Ras Doumeira border area and infiltrating Djiboutian territory. Eritrea denies charge.

- 2008 May – Eritrea calls on UN to terminate peacekeeping mission.

- 2008 June – Fighting breaks out between Eritrean and Djiboutian troops.

- 2016 June – Battle of Tsorona between Eritrean and Ethiopian troops

— BBC[106]

In August 2009, Eritrea and Ethiopia were ordered to pay each other compensation for the war.[106]

In March 2011, Ethiopia accused Eritrea of sending bombers across the border. In April, Ethiopia acknowledged that it was supporting rebel groups inside Eritrea.[106] In July, a United Nations Monitoring Group accused Eritrea of being behind a plot to attack an African Union summit in Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, in January 2011. Eritrea stated the accusation was a total fabrication.[107]

In January 2012, five European tourists were killed and another two were kidnapped close to the border with Eritrea in the remote Afar Region in Ethiopia. In early March the kidnappers announced that they had released the two kidnapped Germans. On 15 March, Ethiopian ground forces attacked Eritrean military posts that they stated were bases in which Ethiopian rebels, including those involved in the January kidnappings, were trained by the Eritreans.[106][108]

See also

References

Notes

Citations

- ↑ "Eritrea accuses Sudan and Ethiopia of conspiracy". The EastAfrican. 16 May 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ↑ Shinn & Ofcansky 2013, pp. 387–388.

- 1 2 "Opposition Group Promises Attacks Following Sanctions on Eritrea for Support of Terrorism". The Jamestown. 7 January 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ↑ "In Eritrea, youth frustrated by long service". The Mail Guardian. 18 July 2008. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- 1 2 "Ethiopian Army". Global Security. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia – Armed forces". Nations Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia Military Strength". Global Firepower. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ↑ Giorgis, Andebrhan Welde (2014). Eritrea at a Crossroads: A Narrative of Triumph, Betrayal and Hope. Strategic Book Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62857-331-2.

- ↑ "Ethiopia, Eritrea officially end war". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia's Abiy and Eritrea's Afewerki declare end of war". BBC News. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ↑ Ramm 1944, pp. 214–215.

- ↑ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 09 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 745–748.

- ↑ Modern Abyssinia. Methuen & Company. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ "Asmara italiana". 6 August 2018. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ↑ "Treaty of Wuchale" (PDF). African Legends. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Prouty 1986, pp. 70–99.

- ↑ Marcus 1995, pp. 111–134.

- ↑ Elliesie 2008, pp. 235–244.

- ↑ Prouty 1986, p. 143.

- ↑ Perham 1948, p. 58.

- ↑ Marcus 1995, p. 175.

- ↑ Marcus 2002, p. 126.

- ↑ Quirico 2002, p. 267.

- ↑ Quirico 2002, p. 271.

- ↑ Quirico 2002, p. 272.

- ↑ Barker 1971, p. 17.

- ↑ Mockler 2003, p. 31.

- ↑ Barker 1971, p. 33.

- ↑ "Ethiopia 1935–36: mustard gas and attacks on the Red Cross". International Committee of the Red Cross. 13 August 2003. Archived from the original on 1 December 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia – Italian East Africa". World States Men. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 1992, p. 54.

- ↑ "How Italy Was Defeated In East Africa In 1941". Imperial War Museums. 18 June 2018. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ↑ Cernuschi 1994, p. 5.

- ↑ Zolberg, Aguayo & Suhrke 1992, p. 106.

- ↑ Mastny 1996, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ "The Big Three After World War II: New Documents on Soviet Thinking about Post-War Relations with the United States and Great Britain" (PDF). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. 13 May 1995. pp. 19–21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Ethiopia and Eritrea". Global Policy Forum. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia : a country study". Kessinger Publishing. 1993. p. 69. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Eritrea Says It Killed 200 Ethiopian Troops in Border Clash". Bloomberg. 16 June 2016. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ↑ "Eritrean People's Liberation Front". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 November 2018. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- 1 2 "Eritrea: A Small War in Africa Volume 10 – Issue 7". Dehai. 1998. Archived from the original on 1 May 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ↑ "Eritrea Birth of a Nation". Dehai. 1993. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ↑ Briggs & Blatt 2009, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ "Eritrea - Ethiopia Relations". Global Security. 10 July 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- 1 2 "Eritrea/Ethiopia War Looms". Foreign Policy in Focus. 2 October 2005. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Border conflict with Ethiopia". Eritrea. Archived from the original on 16 April 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "There are no winners in this insane and destructive war". The Independent. 2 June 2000. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "history". Embassy of the State of Eritrea, New Delhi, India. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ United Nations Security Council Resolution 1312. S/RES/1312(2000) 2000-07-31.

- ↑ "Peace Agreements Digital Collection" (PDF). United States Institute of Peace. 12 December 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "THE WAR REPORT 2018: THE ERITREA–ETHIOPIA ARMED CONFLICT" (PDF). Geneva Academy. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ↑ Astill, James (15 April 2002). "Ethiopia and Eritrea claim border victory". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ↑ "Badme: Village in no man's land". 22 April 2002. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ "Ethiopian official wants border clarification". 23 April 2002. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ "Crucial Horn border talks". 17 September 2003. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- 1 2 "Eritrea firm over disputed border ruling". 25 September 2003. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ "Ethiopia regrets Badme ruling". 3 April 2003. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ "Ethiopia backs down over border". 25 November 2004. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ "Ethiopia 'to reduce' border force". 10 December 2005. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ "Page doesn't exist". www.voanews.com. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ "Ruling: Eritrea broke international law in Ethiopia attack Archived 2006-01-02 at the Wayback Machine" CNN 21 December 2005

- ↑ "Page doesn't exist". www.voanews.com. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ "Horn border tense before deadline". 23 December 2005. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ Eritrea orders Westerners in UN mission out in 10 days, International Herald Tribune, 7 December 2005

- ↑ "Horn rivals reject border plans". 21 November 2006. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Ethiopia 'launches military attack inside Eritrea'". BBC News. 15 March 2012. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Page doesn't exist". www.voanews.com. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ "Eritrea accepts 'virtual' border with Ethiopia". ABC News. 16 January 2008. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ↑ "Security Council ends UN monitoring of Eritrea-Ethiopia row". 30 July 2008. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- 1 2 "Eritrean rebels claim killing 11 government soldiers". Reuters. 23 April 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "'Significant' casualties in Eritrea and Ethiopia border battle". News24. 13 June 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ↑ "Exiled Eritrean rebel groups plan joint military attack against regime". Sudan Tribune. 7 September 2013. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- 1 2 "Border war with Ethiopia (1998-2000)". Global Security. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "Four questions about the Ethiopian PM's resignation". The Daily Monitor. 16 February 2018. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ "UPDATE 3-Ethiopia opens up telecoms, airline to private, foreign investors". Reuters. 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia's PM Abiy Ahmed in Eritrea for landmark visit". al-Jazeera English. 8 July 2018. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia, Eritrea sign statement declaring end of war". France 24. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ↑ Young, John (November 2007). Armed groups along the Ethiopia–Sudan–Eritrea frontier (PDF). Geneva: Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International Studies. p. 32 (PDF 17). ISBN 978-2-8288-0087-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "Free rein for Eritrean opposition". BBC News. 23 May 2000. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ↑ "Battle Breaks Out on Ethiopia-Eritrea Border". U.S. News. 10 July 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia troops head for Baidoa". BBC News. 20 August 2006. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ↑ "Tigray People's Democratic Movement". Global Security. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ↑ "Eritrea cranks' out yet another phantom Ethiopian rebel group made in Eritrea". Tigrai Online. 11 January 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopian opposition leader, Berhanu Nega, 'moves armed operation to Eritrea'". Martinplaut. 25 July 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia claims Eritrea behind Oromo protests but activists warn against 'state propaganda'". International Business Times. 26 February 2018. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia blames Egypt and Eritrea over unrest". BBC News. 16 October 2016. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "About 2,000 Tigray rebels return to Ethiopia from Eritrea". Africa News. 10 October 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ↑ "Eritrea breakthrough as UN sanctions lifted". BBC News. 14 November 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ↑ "Somalia: Eritrean leader in 'historic' visit to Somalia". BBC News. 13 December 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ↑ "Government of Eritrea – Government of Ethiopia". Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ "Eritrean, Ethiopian exchange of POWs begins". CNN. 23 December 2000. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ↑ "Eritrea reveals human cost of war". BBC News. 20 June 2001. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ Shinn & Ofcansky 2013, p. 149.

- ↑ "Woyanne-backed rebels claim killing 285 Eritrean soldiers". Ethiopian Review. 17 November 2008. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "Red Sea Afar rebels attack Eritrean military camp". Sudan Tribune. 26 January 2006. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "Eritrean Rebels Say Kill 25 Government Troops In Attacks". Nazret. 2 January 2010. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "Eritrea profile - Timeline". BBC News. 18 January 2012. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "Eritrean rebels 'kill 12 government troops'". Sudan Tribune. 22 October 2011. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "Eritrea rebels say killed 17 soldiers in raid". Reuters. 1 December 2011. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia: Tourists kidnapped after deadly Afar attack". BBC News. 18 January 2012. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "Ethiopia says four kidnapped in Afar tourist attack". Reuters. 18 January 2012. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "Eritrean rebels kill 7 intelligence agents". Sudan Tribune. 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ↑ "Battle Breaks Out on Ethiopia-Eritrea Border". U.S. News. 10 July 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ↑ "Commemoration of Martyrs Day". Shabait. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Eritrea profile: A chronology of key events". BBC. 4 May 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ↑ BBC staff (28 July 2011). "UN report accuses Eritrea of plotting to bomb AU summit". BBC.

- ↑ "12 years after bloody war, Ethiopia attacks Eritrea". World news on msnbc.com. Reuters. 15 March 2012. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012.

Bibliography

- Abbink, Jon; De Bruijn, Mirjam; Van Walraven, Klass, eds. (2003). Rethinking Resistance: Revolt and Violence in African History. BRILL. ISBN 9789004126244.

- Abbink, Jon 2009, Law against reality? Contextualizing the Ethiopian-Eritrean border problem.'In: Andrea de Guttry, Harry Post & Gabriella Venturini, eds., The 1998–2000 War Between Eritrea and Ethiopia: An International Legal Perspective, pp. 141–158. The Hague: T.M.C. Asser Press – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Abbink, Jon 1998, Briefing: The Eritrean-Ethiopian border dispute. African Affairs 97(389): 551–565.

- Barker, A. J. (1971). Rape of Ethiopia, 1936. Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345024626.

- Briggs, Philip; Blatt, Brian (2009). Ethiopia. Bradt Guides (5, illustrated ed.). Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-284-2.

- Cernuschi, Enrico (1994). "La resistenza sconosciuta in Africa Orientale" [The Unknown Resistance in East Africa]. Rivista storica (in Italian). Roma: Coop. giornalisti storici. OCLC 30747124.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 09 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 745–748.

- Connell, Dan; Killion, Tom (2010). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea – Volume 114 van Historical Dictionaries of Africa. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810875050.

- Elliesie, Hatem (2008). "Amharisch als diplomatische Sprache im Völkervertragsrecht, Aethiopica (International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies)" [Amharic as a diplomatic language in international contract law]. Aethiopica (in German). Wiesbaden.

- Griffith, Francis L.; and seven others (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 09 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 80–130.

- Marcus, Harold G. (1995). The life and times of Menelik II: Ethiopia, 1844–1913. Red Sea Press. ISBN 9781569020098.

- Marcus, Harold G. (2002). A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520925427.

- Mastny, Vojtech (1996). The Cold War and Soviet Insecurity: The Stalin Years. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195352115.

- Mockler, Anthony (2003). Haile Selassie's War. Signal Books. ISBN 9781902669533.

- Perham, Margery (1948). The government of Ethiopia. Faber and Faber. OCLC 641422648.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (1959) [1954]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Early Successes Against Italy (to May 1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. I (4th impr. ed.). HMSO. OCLC 494123451. Retrieved 3 September 2015 – via Hyperwar.

- Prouty, Chris (1986). Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia, 1883–1910. Ravens Educational & Development Services. ISBN 9780932415103.

- Quirico, Domenico (2002). Lo Squadrons Bianco [The Squadrons White] (in Italian). Mondadori. ISBN 9788804506911.

- Ramm, Agatha (1944). "Great Britain and the Planting of Italian Power in the Red Sea, 1868–1885 – The English Historical Review Vol. 59 – No. 234". The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press: 211–236. doi:10.1093/ehr/LIX.CCXXXIV.211. JSTOR 554002.

- Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (1992) [1972]. Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (2nd rev. ed.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-105-9.

- Shinn, David H.; Ofcansky, Thomas P. (2013). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810874572.

- Zolberg, Aristide R.; Aguayo, Sergio; Suhrke, Astri (1992). Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507916-6.

.svg.png.webp)