| Eritrean Railway | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Eritrean railway, that now connects only Massawa and Asmara, showing a class 440 locomotive at work on the mountainous section between Arbaroba and Asmara. | |||

| Overview | |||

| Status | Operational | ||

| Locale | Eritrea | ||

| Termini | |||

| Stations | 13 (originally 31) | ||

| History | |||

| Opened | Between 1887 and 1932 | ||

| Closed | 1975 | ||

| Reopened | 2003 | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 118 kilometres (73 mi) active, full length 337 kilometres (209 mi),) | ||

| Track gauge | 950 mm (3 ft 1+3⁄8 in) | ||

| |||

The Eritrean Railway is the only railway system in Eritrea. It was constructed between 1887 and 1932 during the Italian Eritrea colony and connects the port of Massawa with Asmara.[1] Originally it also connected to Bishia. The line was partly damaged by warfare in subsequent decades, but was rebuilt in the 1990s. Vintage equipment is still used on the line.

Main railway line

Characteristics

The railway was built during Italian Eritrea in order to connect Massawa and Asmara, the main cities of Eritrea.[2]

In the 1930s Italian leader Benito Mussolini wanted to reach Kassala in Sudan, but his war to conquer Ethiopia and create the Italian Empire stopped the enlargement to Agordat and Bishia.

After damage suffered by the railway during World War II, the section between Massawa and Asmara was dismantled partially and was only rebuilt in the 1990s by the Eritrean authorities.

The railway is narrow gauge and is being rebuilt after the devastation wreaked upon it by the war of independence. Its newest equipment is over fifty years old, with most of it predating World War II.

It is one of the few railway systems still in existence (excluding tourist railways) using equipment like the 1930s Italian-built 'Littorina' railcars and 1930s-vintage Mallet steam locomotives.

.jpg.webp)

Route

The railway was fully opened in 1932. It ran from the port of Massawa westwards to Asmara, then extending northwards to Keren, Agordat and Bishia.

It was partially built from Bishia to Tesseney (and projected to reach Kassala, annexed to Eritrea in 1940 by the Italians) at the beginning of World War II, but this section was not finished when the Allies captured Eritrea in 1941.

Until 1978 even the route Asmara-Keren remained partially active. As of 2009, the 118 kilometres (73 mi) section between Massawa and Asmara is open.

950 mm gauge

Eritrea was an Italian colony, and accordingly its railway was built by Italian engineers to Italian standards, using equipment bought from Italy. The gauge chosen was the Italian standard narrow gauge measurement of 950 mm (3 ft 1+3⁄8 in), similar to many common narrow gauge railways under construction in Italy at the same time.

With the short building time and the simultaneous flow of some common equipment and materials to the national railway yards, e.g. metallic plate ties (sleepers), it was necessary to acquire these from France to some extent.

A previous Italian law from 1879 officially established the track gauges, which specified the use of 1,500 mm (4 ft 11+1⁄16 in) and 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) gauge track measured from the centre of the rails, or 1,445 mm (4 ft 8+7⁄8 in) and 950 mm (3 ft 1+3⁄8 in), respectively, on the inside faces.[3]

Construction

Construction began from the Red Sea port city of Massawa in 1887, heading towards the capital city of Asmara. The "Decauville" railway was the first built, from Massaua to Saati, just 27 km.[4] Progress was slow, thanks to the long climb up the mountains to the high plateau of inland Eritrea, and the substantial civil engineering works required; the line reached Asmara in 1911. It was extended to Keren in 1922, Agat in 1925, Agordat in 1928, and finally Bishia in 1932, for a total length of 280 km (174 mi). Bishia (Biscia in Italian) proved to be the end, even though the builders had ambitions of reaching the Sudan Railways line. Mussolini's invasion of Ethiopia led to resources being diverted elsewhere, including the upgrading of the line from Massawa to Asmara to handle more traffic.

Building the line from Massawa to Asmara was a significant undertaking. Even with the tighter turns and narrower right-of-way allowed by a narrow gauge railway, the line required 65 bridges (including a fourteen-arch viaduct crossing the Obel River) and 39 tunnels,[5] the longest being 320 m (1,050 ft). Even so, there were still grades of more than 3%. The highest point on the railway is just east of Asmara at 2,394 m (7,854 ft) above sea level.

The construction of the railway was considered a fine achievement of the first half of the twentieth century.[6]

In operation

In 1935, it carried supplies for the Italian war effort in Ethiopia and the line saw 30 trains daily, while by 1965 the line was carrying nearly half a million passengers a year as well as 200,000 tons of freight. Things went downhill from there. Improvements to the road from Massawa to Asmara, and to the trucks and buses that used it, began to take traffic away from the railway.

Until 1941, the railway was controlled by the Italians, but the fortunes of war allowed the British to take control. After 1942, the railway (damaged during the East Africa Campaign and by Italian guerrillas) was abandoned from Agordat to Biscia.

In 1953, Eritrea was joined to Ethiopia in Federation as the British pulled out, giving Ethiopia a coastline, but starting off 40 years of unrest and eventually war. The first Director General of the railway was Yacob Zanios, a former railway executive from Dire Dawa, who was appointed by HIM Emperor Haile Sellassie to assume management of the railway from the British and organize, rebuild the infrastructure, and integrate the railway into the national transportation grid. Under the four-year leadership of Yacob Zanios, the railway became operational and a very successful enterprise.

The 1950s and 1960s were successful years for the railway, but in the 1970s the railway fell more and more out of use as the mismanagement of the railway and political unrest intensified, and in 1975 the railway was destroyed by the ruling Derg regime in Ethiopia. Much of the infrastructure was destroyed during the following years of war, and both sides used materials salvaged from the railway for fortification and other purposes.

Rebuilding

Eritrea won its independence from Ethiopia in 1993, and in 1994 the Eritrean president declared that rebuilding the railway was a priority for the new nation. During the war years a spirit of self-reliance had been built up, and the Eritreans refused foreign loans and expensive rework. Instead, the Eritreans decided, they would rebuild what they had left with their own efforts. Rebuilding the line started, some work going into rebuilding the workshops and station in Asmara while others set to reconstructing the Massawa end. Renovation of the main line began from Massawa westbound, recovering rails and steel ties.

At the same time, restoration began on the remaining locomotives and rolling stock remaining after the conflict. Eleven steam locomotives survived, and at least six have been rebuilt to working order. In addition, several 1930s vintage Fiat 'Littorina' railcars survive and have been made operational, as well as two of the 1957 Krupp-built B'B'-dh diesel-hydraulics (the line's newest locomotives) and one of three surviving Drewry shunters, brought to the railway by the British during the war years. Finally, several road trucks have been converted to run on rail wheels. Much freight stock and a number of passenger cars also survive.

The line has been restored from Massawa to Asmara, but as of 2006 no scheduled services traverse the whole length of the line. Charter trains for tourists now do, and regular train services exist in certain areas. While the surviving equipment is sufficient for such a limited service, the purchase or building of more is necessary to provide a serious form of transportation over the length of the line. In 2007, The Eritrean Railroad Authority requested funding to continue the Italian-era plan to extend the route to Tesseney and provide an opportunity for Sudan to efficiently use the Port of Massawa. Mining companies in Eritrea have also inquired about use of the railway and its improvement.[7]

The surviving freight cars include a number of larger boxcars suitable for a limited freight service.

Equipment

Steam locomotives

Three classes of steam locomotive still exist; one design of 0-4-0 shunter and two designs of 0-4-4-0 Mallet for line service.

202 Series

These small 0-4-0 tank engines were and are the standard shunter locomotives of the system, built between 1927 and 1937 by the firm of Breda in Milan. They have short side tanks, a rear coal bunker, and a unified, oval dome containing the steam dome inside a larger sand dome. This arrangement, popular worldwide in nations that favored the sand dome, helped both to insulate the steam dome and to keep the sand dry with the warmth. Large, prominent builder's plates adorn the domes. They utilise Walschaerts valve gear with piston valves and superheating, and are painted in the traditional European style of red below the running board, including frames and wheels, and black above, including boiler, cab, tanks etc. The purpose of the red paint is to make cracks and breakages in the locomotive's important running gear more obvious.

Six of these engines survive, of which two were in running order and four in storage awaiting restoration.

440 Series

One of these early Mallet locomotives, which is a true Mallet and thus a compound, still exists in storage at the Asmara workshops. It was a 1915 product of Ansaldo in Genova.

442 Series

These later, and much larger, compound Mallet locomotives were built by Ansaldo in Genova in 1938 to largely replace the earlier types, both the 440 Series and the unsuccessful 441 Series. The latter were simple locomotives (i.e., non-compound) and found liable to run out of steam on the heavy grades of the line. Four of them are still in existence of which three are in running order.

These are the prime main-line steam locomotives of the railway, and are in high demand for tourist services. Two of them, double headed, are required to scale the steepest grades with a train of any length. Like the other locomotives they are tank engines with large side tanks and a rear coal bunker, under cover of the cab roof in this design.

Diesel locomotives

In 1937 TIBB designed a Bo'Bo'-de (diesel-electric) locomotive of 550 hp weighing 44 tonnes, which, however, never operated in Eritrea due to WW II activities [ Source/Reference: http://www.ferroviaeritrea.it/tecnomasio-brown-boveri.html ]. The railway possesses five diesel locomotives today. They are in the process of being returned to working order. Further, a project of sending 11 Italian yard-switchers (Badoni, Ranzi, Greco/Deutz, Zephyr RoadRailer switch locos) to Asmara changing couplers and buffing gear, and re-gauging them to 950 mm was to have been finished by 2018. [ Source/Reference: http://www.ferroviaeritrea.it/progetto-locomotive-italiane-in-eritrea-indice.html ]. To be recognized by their yellow livery.

Krupp B'B'-dh roadswitchers

The railway purchased four Krupp-built 630 hp, 48-tonne, B'B'-dh road switcher locomotives ## 25D - 28D, of typical German offset-cab design in 1957, the newest motive power owned by the system and the only locomotives purchased after World War II. With two of them (## 26D, 28D) having been destroyed by war activities, the remaining two units (## 25D, 27D) are still (intermittently) in working order. In view of the peculiar Krupp-Lysholm-Smith hydrodynamic transmission, spares supplies are proving a problem. When the line's rehabilitation and rebuilding is complete, it is intended to use them for hauling freight. The roadswitchers are painted in a creamy white with brown frames and trucks.

Drewry shunters

Three Drewry Car Co. built diesel shunters are owned by the railway, and were brought to Eritrea by the British after their takeover in 1941. They were previously in service in the Sudan and were of a slightly wider gauge (1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in)) there; they were regauged to the railway's 950 mm (3 ft 1+3⁄8 in) gauge by turning them from an outside framed to an inside framed layout. Two are 0-6-0s and one is an 0-4-0; one of each is working while the third is under repair. They are painted in the same scheme as the Krupp units but lacking their bonnet sides and the engines are exposed.

Railcars

Three Fiat-built 'Littorina' railcars survived the civil war and two are in working order. They are Art Deco in style, with large Fiat radiators on the front. The bodies are painted in creamy white with grey underneath and roofs with red 'bumpers' on the ends and a red stripe separating the body color from the grey below. They are intended for tourist service; new vehicles will be built or bought for regular passenger service.

In addition, one 4-wheel railcar built by Brown Boveri of Switzerland exists out of service in the Asmara shops. It was apparently being used as a mobile generator car before the civil war. It was originally built for Italian Somaliland Railway.

For maintenance an improvised maintenance car is used, a four-wheeler built from a motor-cycle.

Rail trucks

A number of Russian-built Orion light trucks have been converted to run on rail wheels. At present, they are being used in the railway's reconstruction.

Passenger cars

A number of passenger cars, all mounted on two four-wheel trucks, survive. They are fitted with wooden seats and have a platform at each end, one of which is for the brakeman – there are no continuous train brakes on the railway, and braking is either done with the locomotive's brakes or by manually applying the brakes on each car. They are now painted in an attractive livery of white with pale blue in a stripe above the windows and at the bottom of the bodywork.

Freight cars

Abandoned goods wagons sit on sidings near Asmara, and are being restored. Priority is being given to the 8-wheel (2 x 4-wheel truck) boxcars and flatcars, but a large number of 4-wheel (two wheelsets) cars still exist.

Couplings and brakes

Locos and wagons are equipped with a single centre buffer with a hook and screw chain underneath.[8][9] There are no continuous brakes; instead a brakeman travels on each coach to apply braking when required.[10] However, a picture of a tank car shows hoses for some kind of continuous brake.[11]

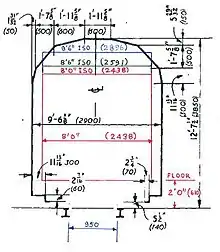

Loading gauge

The structure gauge of the Eritrean Railway is small. Therefore, two test runs, one in 2006 another one in spring 2010 took place when ISO containers were carried on traditional flat wagons through all the tunnels along the line.[12] In December 2010 two ISO Containers of Maersk Line with equipment donated by the Danish State Railway for the rail workshops in Asmara travelled all the line with no problems.[13][14] It is not clear if the containers were 8 ft 6 in (2,591 mm) high or 9 ft 6 in (2,896 mm) high.

Complementary railway lines

The Eritrean Railway was complemented by the Asmara-Massawa Cableway, and by a small transport railway between Mersa Fatma and Colulli, nearly 90 kilometres (56 mi) south of Massawa.

Asmara-Massawa Cableway

The Asmara-Massawa Cableway was built by Italy in the 1930s, and connected the port of Massawa with the city of Asmara. The cableway was the longest of its kind in the world at the time of its inauguration. It had 13 stations with diesel engines, with 1620 little transport wagons. The British later dismantled it during their eleven-year occupation, after defeating Italy in World War II.

Mersa Fatma–Colulli Railway

A 74.5-kilometre (46.3 mi) long 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in) gauge potash transport railway[15] located between Massawa and Assab. A 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in) gauge line was built in 1905 by the Italians inside the port of Mersa Fatma and from it into the hinterland until Colluli near the current Ethiopian border in the Danakil depression with the terminus roughly 35 meters (115 ft) below sea level.[16] Potash production is said to have reached about 50,000 metric tons (49,000 long tons; 55,000 short tons) after this railway was constructed. Production was stopped some years after World War I owing to large-scale supplies mainly from Germany. Unsuccessful attempts to reopen large scale production were made in the period 1920–1941 by the Italian government. Between the years 1925–1929 an Italian company mined 25,000 metric tons (24,600 long tons; 27,600 short tons) of sylvite, averaging 70% KCl, which was transported by rail to Mersa Fatma. The company was the main source of potash in Eritrea and it had to cease most operations because of the Great Depression of 1929.[17]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Asmara italiana

- ↑ 1930s photo of the railway next to the road between Asmara and Massaua

- ↑ "Railroad Gauge Width". Archived from the original on 17 July 2012.

- ↑ Railway Massaua-Saati, built in 1887–1888 (in italian) Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The Eritrean Railway

- ↑ Detailed Map of the Railway between Massaua and Agordat in 1938

- ↑ "Eritrean has sights on rail link to Sudan". 19 January 2007. Archived from the original on 29 January 2007. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- ↑ some scenes show center buffer and chain

- ↑ buffer and chain

- ↑ Allen, Vic (July 2003). "The Land that's Gone Back to Steam". The Railway Magazine. pp. 22–27.

- ↑ "Il Materiale Rotabile". Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ↑ Bernd Seiler: Eritrea – Eisenbahn zwischen Vergangenheit und Zukunft. In: LOK Report, Heft 4, S. 52–58.

- ↑ Christoph Grimm: Hilfsgüter für die Eisenbahn in Eritrea. In: Eisenbahn-Revue International 3/2011, S. 153–155.

- ↑ Farrail – Containers to Asmara

- ↑ "Building the line". Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ↑ Map of Italian Eritrea in 1936 with detailed railway route to Colulli (click on sections 4 and 7)

- ↑ Neil Robinson. World Rail Atlas and Historical Summary. North, East and Central Africa. London, 2009 (p.35-39). ISBN 978-954-92184-3-5

Further reading

- Mitchell, Don (2008). Eritrean Narrow Gauge: An Amazing Reinstatement. Narrow Gauge Branch Lines series. Midhurst, West Sussex, UK: Middleton Press. ISBN 9781906008383.

- Pålsson, Kristina (1998). The Eritrea railway: a study of the motives and circumstances regarding the decision to rehabilitate the old narrow-gauge Eritrean railway. Stockholm: Department of History of Science and Technology, Royal Institute of Technology. OCLC 66433911.

- Robinson, Neil (2009). World Rail Atlas and Historical Summary. Volume 7: North, East and Central Africa. Barnsley, UK: World Rail Atlas Ltd. ISBN 978-954-92184-3-5.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)