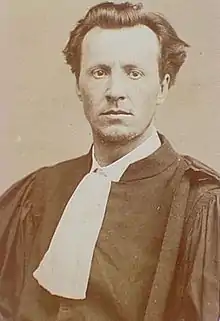

Louis Charles Eugène Protot (27 January 1839 –17 February 1921) was a French lawyer (avocat) and a political opponent of the Second Empire. During the Paris Commune in 1871, he was minister of justice for a month before going into exile until 1880. After his return to France he was prevented from working at the Bar and earned a living as a specialist in Oriental languages.

Under the Second Empire

Protot was born in Carisey in the province of Yonne into a peasant family. Despite the poverty of his background he was able to study law and came to Paris to gain his legal qualifications in 1864. He was an active follower of Auguste Blanqui and wrote articles for the publications Rive gauche and Candide. At the beginning of 1866 he was arrested at a gathering in the Café de la Renaissance in the Place Saint-Michel, together with Gustave Tridon, Raoul Rigault, the Levraud brothers, Gaston Da Costa, Alfred Verlière, Longuet, Genton, Largilière, and Landowski.[1] They were defended by Gustave Chaudey. Protot was sentenced to 15 months in prison.

After qualifying as a lawyer (avocat) he defended opponents of the Second Empire, which brought about his renewed imprisonment. On 1 May 1870 he was arrested[2] for having defended the syndicalist Edmond Mégy, who had murdered a policeman. Protot was found guilty by the High Court sitting at Blois on 30 May for "conspiracy against the life of the Emperor"[3] (Napoleon III).

The Paris Commune

During the Siege of Paris (September 1870 - March 1871), Protot was elected a commandant in the National Guard, and defended certain participants in the uprising of 31 October 1870 against the Government of National Defence. On 18 March 1871, he was called to the Hôtel de Ville by the Comité central ("Central Committee"). On 24 March 1871, with Maxime Lisbonne and Paul Antoine Brunel, he commanded the demonstration against the mairie of the 1st arrondissement of Paris. On 26 March 1871, he was elected to the Council of the Commune (Conseil de la Commune) by the 11th arrondissement, where he proposed and voted on the Decree on Hostages.

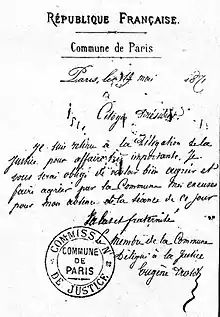

He sat on the Commission of Justice to which he was delegated as minister on 18 April. He led a major policy of reforms and was much concerned with removing from the justice system its aristocratic character. The principal measures he inspired were free justice delivered by elected judges while ensuring guarantees of individual freedom. In particular, he abolished the fees of the ushers and the notaries and ordained that all public offices should prepare without charge the legal documentation within their jurisdiction. However, he had first to overcome the disruption caused by the departure of many officials to Versailles occasioned by the creation of a Chamber of Summary Judgements (Chambre des référés) (26 April) and the appointment of justices of the peace (juges de paix) (3 May) and of examining magistrates (juges d'instruction) (7 and 16 May), pending the complete reconstruction of the civil courts caused by universal suffrage. Protot also tried to obtain a definitive schedule of places of remand and pushed the Commune to establish a commission responsible for visiting the prisons in order to log the complaints of prisoners. Always with the intention of removing everything arbitrary from the legal system, he asked to be kept informed of all the movements of inmates of lunatic asylums.

He fought on the barricades during the "Bloody Week" (Semaine sanglante; 21–28 May 1871). Although injured and disfigured, he managed to escape and fled to Geneva in October 1871 and then Lausanne. He was sentenced to death in his absence by the Council of War in November 1872.

Exile and return

Lucien Descaves in his novel Philémon (1913) describes his life of exile in Switzerland:[4] "Protot, former delegate to the Justice, who lodged, with André Slomszynski, with Pastor Besançon, received a tiny pension from his relatives, did his washing in a basin and assiduously perfected himself in the study of foreign languages, while Slom drew for the Suisse illustrée."

He returned to France after the amnesty of 1880, but the council of the Ordre des avocats (the French equivalent of the Bar Council) refused to reinstate him to the Bar. After unsuccessfully seeking the nomination of the Parisian Blanquistes (who preferred Frédéric Boulé) for the legislative by-election of 27 January 1889 he was a candidate a few months later in Marseille for the seat of Félix Pyat. A determined adversary of Jules Guesde and the Marxists, his opposition focussed on and against the celebration of Labour Day on 1 May by the Marxist socialists of the French Workers' Party. His judgement of Paul Lafargue was severe:[5]

Social democracy has made a place for a son-in-law of the Prussian Karl Marx, the heimatlos Lafargue, a Cuban during the 1870 war so as not to fight his German family, naturalized French by M. Ranc to support the politics of the radicals, elected a French député by the clerical lobby of Lille in order to make an alliance with the papists of the extreme right, introducer of anti-patriotism in France, author of "La Patrie, keksekça?" where the dismemberment of France is predicted as something just, fatal and imminent.

His analysis of Marxism was implacable in its condemnation. In 1892, he wrote in Chauvins et réacteurs:[6]

Under the inspiration of the Social Democrats in Berlin, Marxism has failed French socialism in a well-meaning and contemptuous philanthropy, good treatment of the workers, the concern of the government for the working classes [...] The leaders of this neo-Christian socialism - oligarchs, former officials of the Empire, graduates of Humanities and Sciences - share this insolent prejudice of their caste, that the people are composed of individuals of a lower species [...] The idea of washing people is a monomania of the Marxists.

Protot was also a renowned orientalist, a graduate of the École spéciale des langues orientales in the Arabic and Persian languages, his knowledge of which helped him to gain a living in his last years, and to which he would have liked to have given more time. He contributed to the Revue du monde musulman[7] from 1906 until his death in Paris in 1921.

References

- ↑ Auguste Lepage, Les cafés artistiques et littéraires de Paris, P. Boursin, 1882

- ↑ Histoire de la révolution de 1870-71 Jules Clarétie, Paris, 1877

- ↑ "complot contre la vie de l'Empereur"

- ↑ "Protot, l'ex-délégué à la Justice, qui prenait pension, avec André Slomszynski, chez le pasteur Besançon, recevait des siens une pension modique, lavait son linge dans une cuvette et se perfectionnait assidûment dans l'étude des langues étrangères, tandis que Slom dessinait pour la Suisse illustrée."

- ↑ "La social-démocratie a placé un des gendres du prussien Karl Marx, l'heimatlos Lafargue, cubain pendant la guerre de 1870 pour ne pas combattre sa famille allemande, naturalisé français par M. Ranc, pour appuyer la politique des radicaux, élu député français par l'appoint clérical de Lille, pour faire alliance avec les papistes de l'extrême-droite, introducteur de l'anti-patriotisme en France, auteur de : "La Patrie, keksekça ?" où le démembrement de la France est prédit comme chose juste, fatale et imminente."

- ↑ "Sous l’inspiration des social-démocrates de Berlin, le marxisme a échoué le socialisme français dans une bénigne et méprisante philanthropie, les bons traitements envers les ouvriers, la sollicitude du gouvernement pour les classes laborieuses [...] Les chefs de ce socialisme néo-chrétien, des oligarques, d’anciens fonctionnaires de l’Empire, des gradués des lettres et des sciences, partagent cet insolent préjugé de leur caste, que le peuple est composé d’individus d’une espèce inférieure [...] L’idée de laver le peuple est une monomanie des marxistes."

- ↑ Revue du monde musulman, in December 1922, obituary page 225

Further reading

- Eugène Protot, Manifeste de la Commune révolutionnaire aux travailleurs de France, 1 May 1893.

- Charles Da Costa, Les blanquistes, éditions Rivière, 1912.

- Roger Price, People and politics in France, 1848–1870, Cambridge, 2004.

- Jules Clère, Les hommes de la Commune: Biographie complète de tous ses membres, Paris, Libraire-éditeur É. Dentu, 1871, xiv-195 p., 1 vol. in-18 (OCLC 45798492), pp. 130-132 online version)

- Jules Clère, Les hommes de la Commune: Biographie complète de tous ses membres, Paris, Libraire-éditeur É. Dentu, 1871, 4th edition (1st edition 1871), vi-215 p., 1 vol. in-18, pp. 145-147 (online version)

- Paul Delion, Les membres de la Commune et du Comité central, Paris, A. Lemerre éditeur, August 1871, 446 p. (online version), pp. 167-170

- Bernard Noël, Dictionnaire de la Commune, Coaraze, L'Amourier éditions, coll. « Bio », April 2021 (1st edition 1971), 799 p. (ISBN 9782364180604, ISSN 2259-6976, pp. 650-652

- "Notice Protot Eugène [Protot Louis, Charles, Eugène]" - maitron.fr, Le Maitron, dictionnaire bibliographique du mouvement ouvrier et du mouvement social, Association Les Amis du Maitron (accessed 6 February 2021)