Eugen Richter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader of the Free-minded People's Party | |

| In office 7 May 1893 – 10 March 1906 | |

| Preceded by | Party established |

| Succeeded by | Hermann Müller-Sagan |

| Member of the Reichstag (German Empire) | |

| In office 21 March 1871 – 10 March 1906 | |

| Constituency | Arnsberg 4 (1887-1906) Berlin 5 (1884-1887) Arnsberg 4 (1878-1884) Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt (1871-1878) |

| (North German Confederation) | |

| In office 1867–1871 | |

| Constituency | Nordhausen |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 July 1838 Düsseldorf |

| Died | 10 March 1906 (aged 67) Lichterfelde, Berlin |

| Political party | Free-minded People's Party (1893–1906) |

| Other political affiliations | German Free-minded Party (1884–1893) German Progress Party (1861–1884) |

| Occupation | Journalist, Jurist |

Eugen Richter (30 July 1838 – 10 March 1906) was a German politician and journalist in Imperial Germany. He was one of the leading Old Liberals in the Prussian Landtag and the German Reichstag.[1]

Career

Son of a combat medic, Richter attended the Gymnasium in his home town of Düsseldorf. In 1856 he began to study Law and Economics, first at the University of Bonn, and later at the Berlin and Heidelberg. He obtained a law degree in 1859. Richter became a strong advocate of free trade, a market economy, and a Rechtsstaat; views he held for all his life. In 1859 he became a civil servant in the judiciary. He achieved some renown for his essay Über die Freiheit des Schankgewerbes (On the liberty of the tavern trade). His liberal views caused some trouble with the Prussian bureaucracy. In 1864 he was elected the mayor of Neuwied, but the president of the provincial government refused to confirm his election result. Richter left the civil service, and became the parliamentary correspondent of the Elberfelder Zeitung in Berlin. In 1867 he entered the Reichstag, and after 1869 also became a member of the Prussian Lower House.

He became the leader of the German Progress Party (Deutsche Fortschrittspartei), after 1884 the German Freeminded Party (Deutsche Freisinnige Partei), after 1893 the Freeminded People's Party (Freisinnige Volkspartei), and was one of the leading critics of the policies of Otto von Bismarck. Richter opposed the Anti-Socialist Laws of 1878 that banned the Social Democratic Party. He said: "I fear Social-Democracy more under this law than without it".[2] In response to rumours that Bismarck was planning to introduce a tobacco monopoly, Richter unsuccessfully sought to persuade the Reichstag to pass a resolution that condemned such a monopoly as "economically, financially, and politically unjustifiable".[3] When Bismarck proposed a system of social insurance that was to be paid for by the state, Richter denounced it as "not Socialistic, but Communistic".[4] From 1885 to 1904 he was the chief editor of the liberal newspaper Freisinnige Zeitung.

Political positions

Opposition to socialism

His novel "Pictures of the Socialistic Future" (1891) is a dystopian novel which predicts what would happen to Germany if the socialism espoused by the trade unionists, social democrats, and Marxists was put into practice. He aims to show that government ownership of the means of production and central planning of the economy would lead to shortages, not abundance as the socialists claimed. Written in the form of a diary by a Socialist Revolutionary and former political prisoner who comes to see the horrors his Party unleashes after taking power, the narrator begins by applauding expropriation, the use of lethal force to prevent emigration, and the reassignment of people to new tasks, all the while assuring doubters that an earthly paradise is just around the corner. At one point, however, the narrator asks rhetorically: "What is freedom of the press if the government owns all the presses? What is freedom of religion if the government owns all the houses of worship?" highlighting the abuse of power possible when all property is owned by the state.

It has been described as prescient of what would actually occur in East Germany by Bryan Caplan, an economist, who highlights Richter having predicted several policies which he describes that the East German government really used, such as outlawing emigration and killing those attempting this, as occurred with the Berlin Wall in reality. He also argues that Richter held, unlike some thinkers critical of socialism, such repression is inherent with its actual practice, rather than a defect. He ascribes this to Richter's personal acquaintance with the original leaders of the German socialist movement, and notes that Richter queried them about the very issues he elucidates in the novel.[5]

Opposition to anti-semitism

Anti-semitism was prevalent in the 1870s in Germany, but when the historian Heinrich von Treitschke and the Court Preacher Adolph Stöcker endorsed it in 1879, what had been a fringe phenomenon gained national attention. Various newspapers (such as the "Berliner Antisemitismusstreit") published articles attacking Jews. A petition to the Reich Chancellor Otto von Bismarck called for administrative measures banning Jewish immigration, and restricting their access to positions in education and the judiciary ("Antisemitenpetition", German Wikipedia).

Although anti-semitism was opposed by Eugen Richter's Progress Party and some National Liberals led by Theodor Mommsen and Heinrich Rickert (father of the philosopher Heinrich Rickert), other National Liberals, and the other parties — Conservatives, Center Party, and Socialists — mostly either stayed aloof or flirted with anti-semitism. In November 1880, a declaration by 75 leading scientists, businessmen, and politicians was published in major newspapers condemning anti-semitism ("Notabeln-Erklärung"). It was signed by among others the Mayor of Berlin Max von Forckenbeck, the anthropologist Rudolf Virchow, the historian Theodor Mommsen, and the entrepreneur and inventor Werner Siemens (founder of Siemens AG).[6]

On 20 November 1880 the Progress Party brought the issue before the Prussian Landtag, asking the government to take a stand on whether or not legal restrictions were to be introduced ("Interpellation Hänel"). The government confirmed that the legal status of Jews was not to be altered, but fell short of condemning anti-semitism. Rudolf Virchow complained in the ensuing debate:[7]

Well, meine Herren (Sirs), even if I have called the reply given by the Royal state government correct, I cannot deny that on the whole it could have been somewhat warmer. It was correct, but cold down to the heart.

While on the first day of the debate a consensus seemed to emerge against the anti-semitic movement, on the second day, November 22, 1880 some politicians began to declare their anti-semitism. In his speech, Eugen Richter predicted the eventual consequences of the anti-semitic movement:

Meine Herren, the whole movement has by all means a similar character regarding its final goal, regarding its methods, as the Socialist movement. (Call from the floor.) That is what matters. The small gradual differences completely cede into the background, that is what is particularly insidious about the whole movement, that while the Socialists only turn against the economically better-off, here racial hatred is nourished, that is, something the individual cannot alter and that can only be ended by either killing him or forcing him out of the country.

He concluded his speech with the words:

Exactly to give the government the opportunity to speak its mind, how it stands on the matter, including the Reich Chancellor, that is why we have introduced this interpellation, and we are pleased about the success and wish that from now on throughout the country a sturdy reaction will crush this anti-semitic movement, which truly does not confer honor and adornment on our country.

Responding to an anti-semitic meeting on 17 December 1880, the Progress Party invited all electors for the Prussian Landtag to a meeting in the Reichshallen on 12 January 1881 to demonstrate that the citizens of Berlin did not support anti-semitism. Eugen Richter delivered a speech before an audience of 2.500 electors, attacking anti-semitic university students:[8][9]

And what do we see now as an outrageous phenomenon? Young people who have not lived a great time with a political consciousness like we have — because they were still in 6th and 5th grade (Amusement) — Young people who have not yet proved what they are worth, force their way to the fore and dare to hurl at the Jewish cavaliers of the Iron Cross, and at the fathers who have given their sons to Germany, that they do not belong to the German nation?!! (Longlasting, tempestuous applause. Calls of Boo!)

He turned the anti-semitic accusations around:

Nowadays it is seen as the act of a hero if you drink more than the Jews, and as an educated nation you reproach the Jews for sending so many children to higher education. And after you have worked all those valiant deeds, then you sing: "Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles!" (Tempestuous amusement.) Truly! Our friend Hoffmann von Fallersleben has been saved by a kind fate from experiencing this abuse of his magnificent song. Since, that's something I admit openly, if this is supposed to be German, if this is supposed to be Christian, then I want to be anywhere else in the world but in Christian Germany! (Vigorous applause.)

Already in February 1880, the German Crown Prince and latter Emperor Frederick III had called the anti-semitic movement in a private conversation with the president of the Jewish corporation of Berlin, Meyer Magnus, "a disgrace for Germany" (in some reports also "a disgrace of our time" or "a disgrace for our nation"). Eugen Richter referred to these words, which the Crown Prince confirmed two days later:

One day, it will not be the smallest leaf of laurel in the wreath of our Crown Prince that already at the first stirrings of this movement, something that our deceased colleague Wulffsheim overheard with his own ears and which has also been confirmed otherwise as trustworthy — he declared to the president of the Jewish corporation of Berlin that this movement is a disgrace for the German nation! (Tempestuous, long lasting applause.)

He rejected the claim that the anti-semitic movement had grown from the ranks of craftsmen, workers, and businessmen:

It confers honor on the German craftsmen, workers, and businessmen that this movement, which is supposed to be in their interest, did not arise from their circles, (Vigorous applause), just like the corn tariff propaganda did not arise from peasant circles. It arose from young people who do not earn anything at all, but live out of their parents' pockets. Furthermore, from people who in positions of trust as officials obtain their salaries from the public coffers and often cannot have any idea of how a businessman sometimes feels who struggles to earn his daily bread and to pay the obligatory taxes! (Tempestuous, general applause). Such people who call themselves "educated" have put Jew baiting into action. Indeed, here it shows again that superior mental culture if it is not aligned with a culture of the heart and true religiosity — not a religiosity that has God on its lips, but the devil in its heart — often only leads to nothing more than barbarity in a more refined form!

In his concluding words, he called upon his audience:

In this vein, let us also fight against the depravity of this movement in a league without party distinction, and let us feel united in this resolution — drawing on the New Year's Address of the city councilors to the Kaiser and his reply — that only if all powers of national life, before which no distinction of denominations is justified, working peacefully together, can the welfare of the German Reich and her individual citizens prosper. (Vigorous, continuous applause.)

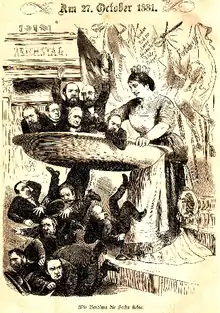

On 27 October 1881 the Progress Party defeated the anti-semitic "Berliner Bewegung" (Berlin Movement), winning all six seats for the capital, with Eugen Richter gaining 66% of the vote in the first round.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Cf. Abbé E. Wetterlé (Representative for Alsace-Lorraine): few men exercised over Parliament an action so powerful as his. When the President granted him leave to speak, all the members gathered around him, for he never left his seat to mount the tribune. ... Bismarck, who could not stand contradiction, used to leave the assembly as soon as Richter began to speak. ... Few debaters had the courage to try their strength with the terrible polemicist. Kardorff and Kanitz, like Bebel and Singer, only reluctantly accepted the struggle with the man who always succeeded in having the laugh on his side. In: Behind the Scenes in the Reichstag, New York, 1918, p.47-48. (online)

- ↑ W. H. Dawson, Bismarck and State Socialism. An Exposition of the Social and Economic Legislation of Germany since 1870 (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1891), p. 44.

- ↑ Dawson, pp. 64-65.

- ↑ A. J. P. Taylor, Bismarck. The Man and the Statesman (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1955), p. 202.

- ↑ Caplan, Bryan (October 14, 2016). "The Dystopian Novel that Foresaw the Nightmares of Socialism". Foundation for Economic Education.

- ↑ Declaration of 75 Notables against Antisemitism (November 12, 1880)

- ↑ Die Judenfrage vor dem Preußischen Landtage. 1880, S. 63, (online, in German), (online, in German)

- ↑ Condemnation of the anti-Semitic Movement by the Electors of Berlin

- ↑ Die Verurtheilung der antisemitischen Bewegung durch die Wahlmänner von Berlin: Bericht über die allgemeine Versammlung d. Wahlmänner aus d. 4. Berliner Landtags-Wahlkreisen am 12. Jan. 1881. C. Bartel, Berlin 1881 (in German)

Further reading

- Ralph Raico (1990). "Eugen Richter and late German Manchester liberalism: A reevaluation". The Review of Austrian Economics. 4 (1): 3–25. doi:10.1007/BF02426362. S2CID 189940578.

External links

- Pictures of the Socialistic Future (1891), David M. Hart.

- Pictures of the Socialistic Future; Swan, Sonnenschein, and Company, London, 1893

- Free download of the novel: https://mises-media.s3.amazonaws.com/Pictures%20of%20the%20Socialistic%20Future_Vol_2_2.pdf