The European exploration of Australia first began in February 1606, when Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon landed in Cape York Peninsula and on October that year when Spanish explorer Luís Vaz de Torres sailed through, and navigated, Torres Strait islands.[1] Twenty-nine other Dutch navigators explored the western and southern coasts in the 17th century, and dubbed the continent New Holland.

Other European explorers followed until, in 1770, Lieutenant James Cook charted the east coast of Australia for Great Britain. Later, after Cook's death, Joseph Banks recommended sending convicts to Botany Bay (now in Sydney), New South Wales. A First Fleet of British ships arrived at Botany Bay in January 1788[2] to establish a penal colony, the first colony on the Australian mainland. In the century that followed, the British established other colonies on the continent, and European explorers ventured into its interior.

Massive areas of land were cleared for agriculture and various other purposes in the first 100 years of European settlement. In addition to the obvious impacts this early clearing of land and importation of hard-hoofed animals had on the ecology of particular regions, it severely affected indigenous Australians, by reducing the resources they relied on for food, shelter and other essentials. This progressively forced them into smaller areas and reduced their numbers as the majority died of newly introduced diseases and lack of resources. Indigenous resistance against the settlers was widespread, and prolonged fighting between 1788 and the 1920s led to the deaths of at least 20,000 indigenous people and between 2,000 and 2,500 Europeans.[3]

History

Earliest European explorations

.jpg.webp)

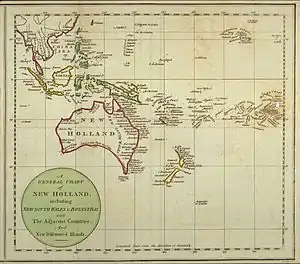

In 1606, Dutch explorers made the first recorded European sightings of, and first recorded landfalls on, the Australian mainland. The first ship and crew to chart the Australian coast and meet with Aboriginal people was the Duyfken captained by Dutch navigator, Willem Janszoon.[4] He sighted the coast of Cape York Peninsula in early 1606, and made landfall on 26 February at the Pennefather River near the modern town of Weipa on Cape York.[5] The Dutch charted the whole of the western and northern coastlines and named the island continent "New Holland" during the 17th century, but made no attempt at settlement.[5] William Dampier, an English explorer and privateer, landed on the north-west coast of New Holland in 1688 and again in 1699 on a return trip.[6]

The Dutch, following shipping routes to the Dutch East Indies to trade in spices, china and silk, proceeded to contribute a great deal to Europe's knowledge of Australia's coast.[7] In 1616, Dirk Hartog, sailing off course, en route from the Cape of Good Hope to Batavia, landed on an island off Shark Bay, West Australia.[7] In 1622–23 the Leeuwin made the first recorded rounding of the south west corner of the continent, and gave her name to Cape Leeuwin.[8]

In 1627, the south coast of Australia was accidentally encountered by François Thijssen and named 't Land van Pieter Nuyts, in honour of the highest ranking passenger, Pieter Nuyts, extraordinary Councillor of India.[9] In 1628 a squadron of Dutch ships was sent by the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies Pieter de Carpentier to explore the northern coast. These ships made extensive examinations, particularly in the Gulf of Carpentaria, named in honour of de Carpentier.[8]

Abel Tasman's voyage of 1642 was the first known European expedition to reach Van Diemen's Land (later Tasmania) and New Zealand, and to sight Fiji. On his second voyage of 1644, he also contributed significantly to the mapping of Australia proper, making observations on the land and people of the north coast below New Guinea.[10]

A map of the world inlaid into the floor of the Burgerzaal ("Burger's Hall") of the new Amsterdam Stadhuis ("Town Hall") in 1655 revealed the extent of Dutch charts of much of Australia's coast.[11] Based on the 1648 map by Joan Blaeu, Nova et Accuratissima Terrarum Orbis Tabula, it incorporated Tasman's discoveries, subsequently reproduced in the map, Archipelagus Orientalis sive Asiaticus published in the Kurfürsten Atlas (Atlas of the Great Elector).[12]

In 1664, the French geographer Melchisédech Thévenot published a map of New Holland in Relations de Divers Voyages Curieux.[13] Thévenot divided the continent in two, between Nova Hollandia to the west and Terre Australe to the east.[14] Emanuel Bowen reproduced Thevenot's map in his Complete System of Geography (London, 1747), re-titling it A Complete Map of the Southern Continent and adding three inscriptions promoting the benefits of exploring and colonising the country. One inscription said:

It is impossible to conceive a Country that promises fairer from its Situation than this of TERRA AUSTRALIS, no longer incognita, as this Map demonstrates, but the Southern Continent Discovered. It lies precisely in the richest climates of the World... and therefore whoever perfectly discovers and settles it will become infalliably possessed of Territories as Rich, as fruitful, and as capable of Improvement, as any that have hitherto been found out, either in the East Indies or the West.

In 1770, James Cook sailed along and mapped the east coast, which he named New South Wales and claimed for Great Britain.[15]

Colonisation

With the loss of its American colonies in 1783, the British Government sent a fleet of ships, the "First Fleet", under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, to establish a new penal colony in New South Wales. A camp was set up and the flag raised at Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, on 26 January 1788,[16] a date which became Australia's national day, Australia Day. Phillip sent exploratory missions in search of better soils, fixed on the Parramatta region as a promising area for expansion, and moved many of the convicts from late 1788 to establish a small township, which became the main centre of the colony's economic life.[17][18]

Seventeen years after Cook's landfall on the east coast of Australia, the British government decided to establish a colony at Botany Bay. Following the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), Britain lost most of its territory in North America and considered establishing replacement colonies. In 1779 Sir Joseph Banks, the eminent scientist who had accompanied James Cook on his 1770 voyage, recommended Botany Bay as a suitable site for settlement, saying that "it was not to be doubted that a Tract of Land such as New Holland, which was larger than the whole of Europe, would furnish Matter of advantageous Return".[19]

Georg Forster, who had sailed under Lieutenant James Cook in the voyage of HMS Resolution (1772–1775), wrote in 1786 on the future prospects of the British colony: "New Holland, an island of enormous extent or it might be said, a third continent, is the future homeland of a new civilized society which, however mean its beginning may seem to be, nevertheless promises within a short time to become very important."[20]

Britain claimed territory encompassing all of Australia eastward of the meridian of 135° East and all the islands in the Pacific Ocean between the latitudes of Cape York and the southern tip of Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania). The western limit of 135° East was set at the meridian dividing New Holland from Terra Australis, as shown on Emanuel Bowen's Complete Map of the Southern Continent,[21] published in John Campbell's editions of John Harris' Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, or Voyages and Travels (1744–1748, and 1764).[22] It was a vast claim which elicited excitement at the time: the Dutch translator of First Fleet officer and author Watkin Tench's A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay wrote: "a single province which, beyond all doubt, is the largest on the whole surface of the earth. From their definition it covers, in its greatest extent from East to West, virtually a fourth of the whole circumference of the Globe."[23]

A British settlement was established in 1803 in Van Diemen's Land, now known as Tasmania, and it became a separate colony in 1825.[24] The United Kingdom formally claimed the western part of Western Australia (the Swan River Colony) in 1828.[25] Separate colonies were carved from parts of New South Wales: South Australia in 1836, Victoria in 1851, and Queensland in 1859.[26] The Northern Territory was founded in 1911 when it was excised from South Australia.[27] South Australia was founded as a "free province"—it was never a penal colony.[28] Victoria and Western Australia were also founded "free", but later accepted transported convicts.[29][30] A campaign by the settlers of New South Wales led to the end of convict transportation to that colony; the last convict ship arrived in 1848.[31]

Exploration of the continent

Early days

In 1798–99 George Bass and Matthew Flinders set out from Sydney in a sloop and circumnavigated Tasmania, thus proving it to be an island, following a failed attempt to settle at Sullivan Bay in what is now Victoria.[32] In 1801–02 Matthew Flinders in HMS Investigator led the first circumnavigation of Australia. Aboard ship was the Aboriginal explorer Bungaree, of the Sydney district, who became the first person born on the Australian continent to circumnavigate the Australian continent.[32] Previously, the famous Bennelong and a companion had become the first people born in the area of New South Wales to sail for Europe, when, in 1792 they accompanied Governor Phillip to England and were presented to King George III.[32]

In 1813, Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson and William Wentworth succeeded in crossing the formidable barrier of forested gulleys and sheer cliffs presented by the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney. At Mount Blaxland they looked out over "enough grass to support the stock of the colony for thirty years", and expansion of the British settlement into the interior could begin.[33]

1820s–1830s

In 1824 the Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane commissioned Hamilton Hume and former Royal Navy Captain William Hovell to lead an expedition to find new grazing land in the south of the colony, and also to find an answer to the mystery of where New South Wales' western rivers flowed. Over 16 weeks in 1824–25, Hume and Hovell journeyed to Port Phillip and back. They made many important discoveries including the Murray River (which they named the Hume), many of its tributaries, and good agricultural and grazing lands between Gunning, New South Wales and Corio Bay, Port Phillip.[34]

Charles Sturt led an expedition along the Macquarie River in 1828, becoming the first European to encounter the Darling River. A theory had developed that the inland rivers of New South Wales were draining into an inland sea. Leading a second expedition in 1829, Sturt followed the Murrumbidgee River into a 'broad and noble river', the Murray River, which he named after Sir George Murray, secretary of state for the colonies. His party followed this river to its junction with the Darling River, facing two threatening encounters with local Aboriginal people along the way. Sturt continued down river to Lake Alexandrina, where the Murray meets the sea in South Australia. Suffering greatly, the party had to row hundreds of kilometres back upstream for the return journey.[35]

Surveyor General Sir Thomas Mitchell conducted a series of expeditions from the 1830s to 'fill in the gaps' left by these previous expeditions. He was meticulous in seeking to record the original Aboriginal place names around the colony, for which reason the majority of place names to this day retain their Aboriginal titles.[36]

In 1836, two ships of the South Australia Land Company left to establish the first settlement on Kangaroo Island. The foundation of South Australia is now generally commemorated as Governor John Hindmarsh's Proclamation of the new Province at Glenelg, on the mainland, on 28 December 1836.[37]

The Polish scientist/explorer Count Paul Edmund Strzelecki conducted surveying work in the Australian Alps in 1839. He became the first European to ascend Australia's highest peak, which he named Mount Kosciuszko in honour of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kościuszko.[38]

Other British settlements followed, at various points around the continent, many of them unsuccessful. The East India Trade Committee recommended in 1823 that a settlement be established on the coast of northern Australia to forestall the Dutch, and Captain J.J.G. Bremer, RN, was commissioned to form a settlement between Bathurst Island and the Cobourg Peninsula. Bremer fixed the site of his settlement at Fort Dundas on Melville Island in 1824. Because this was well to the west of the boundary proclaimed in 1788, he proclaimed British sovereignty over all the territory as far west as longitude 129° East.[39]

The new boundary included Melville and Bathurst islands, and the adjacent mainland. In 1826, the British claim was extended to the whole Australian continent when Major Edmund Lockyer established a settlement on King George Sound (the basis of the later town of Albany), but the eastern border of Western Australia remained unchanged at longitude 129° East. In 1824, a penal colony was established near the mouth of the Brisbane River (the basis of the later colony of Queensland). In 1829, the Swan River Colony and its capital of Perth were founded on the west coast proper and also assumed control of King George Sound. Initially a free colony, Western Australia later accepted British convicts, because of suffering a lack of settlers and an acute labour shortage.

The colony of South Australia was settled in 1836, with its western and eastern boundaries set at 132° and 141° East of Greenwich, and to the north at latitude 26° South.[40] The western and eastern boundary points were chosen as they marked the extent of coastline first surveyed by Matthew Flinders in 1802 (Nicolas Baudin's priority being ignored). The British Parliament set the northern boundary at the parallel of latitude 26° South, because they believed that was the limit of effective control of territory that could be exercised by a settlement founded on the shores of Gulf St Vincent. The South Australian Company had proposed the parallel of 20° South, later reduced to the Tropic of Capricorn (the parallel of latitude 23° 37′ South).[41]

Into the interior

European explorers made their last great, often arduous and sometimes tragic expeditions into the interior of Australia during the second half of the 19th century—some with the official sponsorship of the colonial authorities and others commissioned by private investors. By 1850, large areas of the inland were still unknown to Europeans. Trailblazers like Edmund Kennedy and the Prussian naturalist Ludwig Leichhardt had met tragic ends attempting to fill in the gaps during the 1840s, but explorers remained ambitious to discover new lands for agriculture or answer scientific enquiries. Surveyors also acted as explorers and the colonies sent out expeditions to discover the best routes for lines of communication. The size of expeditions varied considerably from small parties of just two or three to large, well-equipped teams led by gentlemen explorers assisted by smiths, carpenters, labourers and Aboriginal guides accompanied by horses, camels or bullocks.[42]

From 1858 onwards, the so-called "Afghan" cameleers and their beasts played an instrumental role in opening up the outback and helping to build infrastructure.[43]

In 1860, the ill-fated Burke and Wills led the first north-south crossing of the continent from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Lacking bushcraft and unwilling to learn from the local Aboriginal people, Burke and Wills died in 1861, having returned from the Gulf to their rendezvous point at Coopers Creek only to discover the rest of their party had departed the location only a matter of hours previously. Though an impressive feat of navigation, the expedition was an organisational disaster which continues to fascinate the Australian public.

In 1862, John McDouall Stuart succeeded in traversing Central Australia from south to north. His expedition mapped out the route which was later followed by the Australian Overland Telegraph Line.[44]

Uluru and Kata Tjuta were first mapped by Europeans in 1872 during the expeditionary period made possible by the construction of the Australian Overland Telegraph Line. In separate expeditions, Ernest Giles and William Gosse were the first European explorers to this area. While exploring the area in 1872, Giles sighted Kata Tjuta from a location near Kings Canyon and called it Mount Olga, while the following year Gosse observed Uluru and named it Ayers Rock, in honour of the Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers. These barren desert lands of Central Australia disappointed the Europeans as unpromising for pastoral expansion, but would later come to be appreciated as emblematic of Australia.

References

- ↑ Brett Hilder (1980) The Voyage of Torres. University of Queensland Press, St. Lucia, Queensland. ISBN 0-7022-1275-X

- ↑ Lewis, Balderstone and Bowan (2006) p. 25

- ↑ Grey, Jeffrey (2008). A Military History of Australia (Third ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. pp. 28–40. ISBN 978-0-521-69791-0.

- ↑ "European discovery and the colonisation of Australia – European mariners". Government of Australia. Government of Australia. 2015. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- 1 2 Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, p. 233.

- ↑ Marsh, Lindsay (2010). History of Australia : understanding what makes Australia the place it is today. Greenwood, W.A.: Ready-Ed Publications. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-86397-798-2.

- 1 2 Manning Clark; A Short History of Australia; Penguin Books; 2006; p. 6

- 1 2 "INTERESTING HISTORICAL NOTES". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas.: National Library of Australia. 9 October 1923. p. 5. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ↑ "NUYTS TERCENTENARY". The Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 24 May 1927. p. 11. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Tasman, Abel". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

- Edward Duyker (ed.) The Discovery of Tasmania: Journal Extracts from the Expeditions of Abel Janszoon Tasman and Marc-Joseph Marion Dufresne 1642 & 1772, St David's Park Publishing/Tasmanian Government Printing Office, Hobart, 1992, p. 106, ISBN 0-7246-2241-1.

- ↑ A floor plan of the Groote Burger-Zaal (Great Salon of Burgesses) in the Amsterdam Town Hall, including the engraved map of the world, was published in Jacob van Campen, Jacob Vennekool and Danckert Danckerts, Afbeelding van't Stadt Huys van Amsterdam in dartigh coopere Plaaten [Depiction of Amsterdam town hall on thirty copper plates], Amsterdam, 1661; Jacob van Campen, Jacob Vennekool and Danckert Danckerts, De gront en vloer vande Groote Burger-Zaal (View of the floor of the Civic Hall) geordineert door Jacob van Campen en geteeckent door Jacob Vennekool met Speciael Octroy van de Heeren Staten voor 15 Jaren, 1661, reproduced in Margaret Cameron Ash, "French Mischief: A Foxy Map of New Holland", The Globe, No. 68, 2011, pp. 1–14.

- ↑ National Library of Australia, Maura O'Connor, Terry Birtles, Martin Woods and John Clark, Australia in Maps: Great Maps in Australia's History from the National Library's Collection, Canberra, National Library of Australia, 2007, p. 32; this map is reproduced in Gunter Schilder, Australia Unveiled, Amsterdam, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1976, p. 402; and in William Eisler and Bernard Smith, Terra Australis: The Furthest Shore, Sydney, International Cultural Corporation of Australis, 1988, pp. 67–84. Image at: home

- ↑ Melchisedech Thévenot, Relations de divers Voyages curieux qui n 'ont point esté publiées, Paris, Thomas Moette, IV, 1664.

- ↑ Sir Joseph Banks, 'Draft of proposed Introduction to Captn Flinders Voyages', November 1811; State Library of New South Wales, The Papers of Sir Joseph Banks, Series 70.16; quoted in Robert J. King, "Terra Australis, New Holland and New South Wales: the Treaty of Tordesillas and Australia", The Globe',' No. 47, 1998, pp. 35–55

- ↑ "European discovery and the colonisation of Australia". Australian Government: Culture Portal. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Commonwealth of Australia. 11 January 2008. Archived from the original on 16 February 2011.

- ↑ "European discovery and the colonisation of Australia". Australian Government: Culture Portal. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Commonwealth of Australia. 11 January 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

[The British] moved north to Port Jackson on 26 January 1788, landing at Camp Cove, known as 'cadi' to the Cadigal people. Governor Phillip carried instructions to establish the first British Colony in Australia. The First Fleet was under prepared for the task, and the soil around Sydney Cove was poor.

- ↑ "AUSTRALIAN ALMANAC". The Australian Women's Weekly. National Library of Australia. 15 February 1967. p. 35. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ Phillip cited in Trina Jeremiah; "Immigrants and Society" in T. Gurry (1984) pp. 121–22

- ↑ Journals of the House of Commons, 19 Geo. III, 1779, p. 311 ; John Gascoigne, Science in the Service of Empire: Joseph Banks, the British State and the Uses of Science in the Age of Revolution, Melbourne, Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 187.

- ↑ Georg Forster, "Neuholland und die brittische Colonie in Botany-Bay", Allgemeines historisches Taschenbuch, (Berlin, December 1786), English translations at web.mala.bc.ca Archived 5 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine and at australiaonthemap.org.au Archived 19 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ A Complete map of the Southern Continent survey'd by Capt. Abel Tasman & depicted by order of the East India Company in Holland in the Stadt House at Amsterdam; E. Bowen, Sculp.

- ↑ Robert J. King, "Terra Australis, New Holland and New South Wales: the Treaty of Tordesillas and Australia", The Globe, No. 47, 1998, pp. 35–55, 48–49.

- ↑ Beschrijving van den Togt Naar Botany-Baaij....door den Kapitein Watkin Tench, Amsterdam, Martinus de Bruijn, 1789, p. 211.

- ↑ Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, pp. 464–65, 628–29.

- ↑ Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, p. 678.

- ↑ Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, p. 464.

- ↑ Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, p. 470.

- ↑ Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, p. 598.

- ↑ Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, p. 679.

- ↑ Convict Records Public Record office of Victoria; State Records Office of Western Australia Archived 30 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "1998 Special Article – The State of New South Wales – Timeline of History". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1988.

- 1 2 3 Macrae, Keith. "Bass, George (1771–1803)". Biography – George Bass – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ Conway, Jill. "Blaxland, Gregory (1778–1853)". Biography – Gregory Blaxland – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ Hume, Stuart H. (17 August 1960). "Hume, Hamilton (1797–1873)". Biography – Hamilton Hume – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ H.J. Gibbney. "Sturt, Charles (1795–1869)". Biography – Charles Sturt – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ D.W.A. Baker. "Mitchell, Sir Thomas Livingstone (1792–1855)". Biography – Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ "Foundingdocs.gov.au". Foundingdocs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2 June 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ Heney, Helen. "Strzelecki, Sir Paul Edmund de (1797–1873)". Biography – Sir Paul Edmund de Strzelecki – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ Historical Records of Australia, Series III, Vol. V, 1922, pp. 743–47, 770.

- ↑ Letters Patent establishing the Province of South Australia, in Brian Dickey and Peter Howell, South Australia's Foundation: Select Documents, Adelaide, Wakefield Press Netley, 1986, p. 75

- ↑ South Australian Association, South Australia: Outline of the Plan of a Proposed Colony to be Founded on the South Coast of Australia, London, Ridgway, 1834, p. 6; Henry Capper and William Light, South Australia: Extracts from the Official Dispatches of Colonel Light, ... letters of settlers ... [and] the proceedings of the South Australian Company, London, H. Capper, 1837, p. 21; Peter Howell, "The Passing of South Australia's Foundation Bill, 1834", Flinders Journal of History and Politics, Vol. 11, 1985, pp. 25–41, p. 35; Peter Howell, "The South Australia Act, 1834", in Dean Jaensch (ed.), The Flinders History of South Australia: Political History, Netley, Wakefield Press, 1986, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ "Early explorers - Australia's Culture Portal". Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ "Afghan cameleers in Australia". australia.gov.au. 15 August 2014. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ↑ Tim Flannery; The Explorers; Text Publishing 1998

Further reading

- Edward John Eyre (1843). "Expeditions of Discovery in South Australia". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 13: 161–182. ISSN 0266-6235. Wikidata Q108704393.

- Allan Cunningham (1832). "Brief View of the Progress of Interior Discovery in New South Wales". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 2: 99–132. doi:10.2307/1797758. ISSN 0266-6235. Wikidata Q108673781.

- George Grimm (1888), The Australian explorers: their labours, perils and achievements being a narrative of discovery from the landing of Captain Cook to the centennial year (1st ed.), Melbourne: George Robertson & Company, Wikidata Q109547533

Sources

- Davison, Graeme; Hirst, John; Macintyre, Stuart (1998). The Oxford Companion to Australian History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-553597-6.