Eusapia Palladino (alternative spelling: Paladino; 21 January 1854 – 16 May 1918) was an Italian Spiritualist physical medium.[1][2] She claimed extraordinary powers such as the ability to levitate tables, communicate with the dead through her spirit guide John King, and to produce other supernatural phenomena.

She convinced many persons of her powers, but was caught in deceptive trickery throughout her career.[3][4][5][6] Magicians, including Harry Houdini, and skeptics who evaluated her claims concluded that none of her phenomena were genuine and that she was a clever trickster.[7][8][9][10]

Her Warsaw séances at the turn of 1893–94 inspired several colorful scenes in the historical novel Pharaoh, which Bolesław Prus began writing in 1894.

Early life

Palladino was born into a peasant family in Minervino Murge, Bari Province, Italy. She received little, if any, formal education.[11][12] Orphaned as a child, she was taken in as a nursemaid by a family in Naples. In her early life, she was married to a travelling conjuror and theatrical artist, Raphael Delgaiz, whose store she helped manage.[13][14] Palladino later married a wine merchant, Francesco Niola.[15]

Poland

Palladino visited Warsaw, Poland, on two occasions. Her first and longer visit was when she came at the importunities of the psychologist, Dr. Julian Ochorowicz, who hosted her from November 1893 to January 1894.[16]

Regarding the phenomena demonstrated at Palladino's séances, Ochorowicz concluded against the spirit hypothesis and for a hypothesis that the phenomena were caused by a "fluidic action" and were performed at the expense of the medium's own powers and those of the other participants in the séances.[17]

Ochorowicz introduced Palladino to the journalist and novelist Bolesław Prus, who attended a number of her séances, wrote about them in the press, and incorporated several Spiritualist-inspired scenes into his historical novel Pharaoh.

On 1 January 1894 Palladino called on Prus at his apartment. As described by Ochorowicz,

"In the evening she visited Prus, whom she always adored. Though their conversation was original, because the one did not know Polish and the other Italian, when il Prusso entered she went mad with joy and they somehow managed to communicate with one another. So she saw it as her obligation to pay him a New Year's visit."[18]

Palladino subsequently visited Warsaw in the second half of May 1898, on her way from St. Petersburg to Vienna and Munich. At that time, Prus attended at least two of the three séances that she conducted (the two séances were held in the apartment of Ludwik Krzywicki).[19]

England

In July 1895, Palladino was invited to England to Frederic William Henry Myers's house in Cambridge for a series of investigations into her mediumship. According to reports by the investigators Myers and Oliver Lodge, all the phenomena observed in the Cambridge sittings were the result of trickery. Her fraud was so clever, according to Myers, that it "must have needed long practice to bring it to its present level of skill."[20]

In the Cambridge sittings, the results proved disastrous for her mediumship. During the séances Palladino was caught cheating in order to free herself from the physical controls of the experiments.[4] Palladino was found liberating her hands by placing the hand of the controller on her left on top of the hand of the controller on her right. Instead of maintaining any contact with her, the observers on either side were found to be holding each other's hands and this made it possible for her to perform tricks.[21] Richard Hodgson had observed Palladino free a hand to move objects and use her feet to kick pieces of furniture in the room. Because of the discovery of fraud, the British SPR investigators such as Henry Sidgwick and Frank Podmore considered Palladino's mediumship to be permanently discredited, and because of her fraud she was banned from any further experiments with the SPR in Britain.[21] The magician John Nevil Maskelyne, who was involved in the investigation, supported Hodgson's conclusion.[6] However, despite the evidence of fraud, Oliver Lodge considered some of her phenomena genuine.[22]

In the Daily Chronicle on 29 October 1895, Maskelyne published a long exposure of Palladino's fraudulent methods. According to historian Ruth Brandon "Maskelyne concluded that everything rested on the question whether Eusapia could get a hand or foot free occasionally. She wriggled so much that it was impossible to control her properly throughout. If she could get one hand, and sometimes a foot, free, everything could be explained."[23]

In the British Medical Journal on 9 November 1895 an article was published titled Exit Eusapia!. The article questioned the scientific legitimacy of the SPR for investigating Palladino a medium who had a reputation of being a fraud and imposture.[24] Part of the article read "It would be comic if it were not deplorable to picture this sorry Egeria surrounded by men like Professor Sidgwick, Professor Lodge, Mr. F. H. Myers, Dr. Schiaparelli, and Professor Richet, solemnly receiving her pinches and kicks, her finger skiddings, her sleight of hand with various articles of furniture as phenomena calling for serious study."[24] This caused Henry Sidgwick to respond in a published letter to the British Medical Journal of 16 November 1895. According to Sidgwick SPR members had exposed the fraud of Palladino at the Cambridge sittings. Sidgwick wrote "Throughout this period we have continually combated and exposed the frauds of professional mediums, and have never yet published in our Proceedings, any report in favour of the performances of any of them."[25] The response from the "BMJ" questioned why the SPR wasted time investigating phenomena that were the "result of jugglery and imposture" and did not urgently concern the welfare of mankind.[25]

In 1898, Myers was invited to a series of séances in Paris with Charles Richet. In contrast to the previous séances in which he had observed fraud, he now claimed to have observed convincing phenomena.[26] Sidgwick reminded Myers of Palladino's trickery in the previous investigations as "overwhelming" but Myers did not change his position. This enraged Richard Hodgson, then editor of SPR publications, who banned Myers from publishing anything on his recent sittings with Palladino in the SPR journal. Hodgson was convinced Palladino was a fraud and supported Sidgwick in the "attempt to put that vulgar cheat Eusapia beyond the pale."[26] It wasn't until the 1908 sittings in Naples that the SPR reopened the Palladino file.[27]

The British psychical researcher Harry Price, who studied Palladino's mediumship, wrote "Her tricks were usually childish: long hairs attached to small objects in order to produce 'telekinetic movements'; the gradual substitution of one hand for two when being controlled by sitters; the production of 'phenomena' with a foot which had been surreptitiously removed from its shoe and so on."[28]

France

The French psychical researcher Charles Richet with Oliver Lodge, Frederic William Henry Myers and Julian Ochorowicz investigated the medium Palladino in the summer of 1894 at his house in the Ile Roubaud in the Mediterranean. Richet claimed furniture moved during the séance and that some of the phenomena was the result of a supernatural agency.[4] However, Richard Hodgson claimed there was inadequate control during the séances and the precautions described did not rule out trickery. Hodgson wrote all the phenomena "described could be account for on the assumption that Eusapia could get a hand or foot free." Lodge, Myers and Richet disagreed, but Hodgson was later proven correct in the Cambridge sittings as Palladino was observed to have used tricks exactly the way he had described them.[4]

In 1898, the French astronomer Eugene Antoniadi investigated the mediumship of Palladino at the house of Camille Flammarion. According to Antoniadi her performance was "fraud from beginning to end". Palladino tried constantly to free her hands from control and was caught lowering a letter-scale by means of a hair.[20]

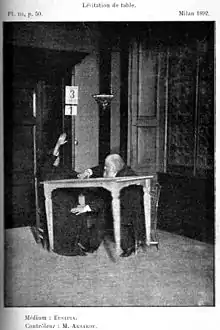

Flammarion, who attended séances with Palladino, believed that some of her phenomena were genuine. He produced in his book alleged levitation photographs of a table and an impression of a face in putty.[29] Joseph McCabe did not find the evidence convincing. He stated that the impressions of faces in putty were always of Palladino's face and could have easily been made, and she was not entirely clear from the table in the levitation photographs.[30]

In 1905, Eusapia Palladino came to Paris, where Nobel-laureate physicists Pierre Curie and Marie Curie and Nobel-laureate physiologist Charles Richet investigated her amongst other philosophers and scientists such as Henri Bergson and Jacques-Arsène d'Arsonval. Signs of trickery were detected but they could not explain all of the phenomena.[31]

Other members of the Curies' circle of scientist friends—including William Crookes; future Nobel laureate Jean Perrin and his wife Henriette; Louis Georges Gouy; and Paul Langevin—were also exploring spiritualism, as was Pierre Curie's brother Jacques, a fervent believer.[32]

The Curies regarded mediumistic séances as "scientific experiments" and took detailed notes. According to historian Anna Hurwic, they thought it possible to discover in spiritualism the source of an unknown energy that would reveal the secret of radioactivity.[32] On July 24, 1905, Pierre Curie reported to his friend Gouy: "We have had a series of séances with Eusapia Palladino at the [Society for Psychical Research]."

It was very interesting, and really the phenomena that we saw appeared inexplicable as trickery—tables raised from all four legs, movement of objects from a distance, hands that pinch or caress you, luminous apparitions. All in a [setting] prepared by us with a small number of spectators all known to us and without a possible accomplice. The only trick possible is that which could result from an extraordinary facility of the medium as a magician. But how do you explain the phenomena when one is holding her hands and feet and when the light is sufficient so that one can see everything that happens?[33]

Pierre was eager to enlist Gouy. Palladino, he informed him, would return in November, and "I hope that we will be able to convince you of the reality of the phenomena or at least some of them." Pierre was planning to undertake experiments "in a methodical fashion."[33] Marie Curie also attended Palladino's séances, but does not seem to have been as intrigued by them as Pierre.[33]

On 14 April 1906, just five days before his accidental death, Pierre Curie wrote Gouy about his last séance with Palladino: "There is here, in my opinion, a whole domain of entirely new facts and physical states in space of which we have no conception."[33]

Professors Gustave Le Bon and Albert Dastre of Paris University examined Palladino in 1906 and concluded that she was a cheat. They installed a secret lamp behind Palladino and, at a séance, saw her release and use her foot.[34] In 1907, Palladino was found using a strand of her hair to move an object toward herself and it was noted by investigators that the objects were not outside of her easy reach.[35]

Italy

In the late 19th century, the criminologist Cesare Lombroso attended séances with Palladino and was convinced that she had supernatural powers.[36] Lombroso was persuaded by Palladino's manager, Ercole Chiaia, to attend her séances. Chiaia challenged him in an open letter in the magazine La Fanfulla, pointing out that if Lombroso was unbiased and free of prejudice, he should be willing to investigate her phenomena. Initially, Lombroso rejected the challenge, which was accepted by a young Spanish physician, Manuel Otero Acevedo, who travelled to Naples, studied Palladino and convinced Lombroso, Aksakof and other scientists of the importance of investigating her phenomena.[37] Lombroso's subsequent conversion, reported by the press in Italy and the world, was instrumental to Palladino's reaching celebrity status at the turn of the century.[38]

Most extraordinary was a phenomenon that Lombroso dubbed "The Levitation of the Medium to the Top of the Table."[39] However, other investigators found the levitations of the table to be fraudulent.[6] According to authors William Kalush and Larry Sloman, Lombroso was having a sexual relationship with Palladino.[40] Lombroso's daughter Gina Ferrero wrote that, in his later years, Lombroso suffered from arteriosclerosis and his mental and physical health was wrecked. Joseph McCabe wrote that because of this it is not surprising that Palladino managed to fool him with her tricks.[41]

Enrico Morselli was also interested in mediumship and psychical research. He studied Palladino and concluded that some of her phenomena were genuine – evidence for an unknown bio-psychic force present in all humans.[42]

In 1908, the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) appointed a committee of three to examine Palladino in Naples. The committee comprised Mr. Hereward Carrington, investigator for the American Society for Psychical Research and an amateur conjurer; Mr. W. W. Baggally, also an investigator and amateur conjurer of much experience; and the Hon. Everard Feilding, who had had an extensive training as investigator and "a fairly complete education at the hands of fraudulent mediums."[10] Three adjoining rooms on the fifth floor of the Hotel Victoria were rented. The middle room where Feilding slept was used in the evening for the séances.[43] In the corner of the room was a séance cabinet created by a pair of black curtains to form an enclosed area that contained a small round table with several musical instruments. In front of the curtains was placed a wooden table. During the séances, Palladino would sit at this table with her back to the curtains. The investigators sat on either side of her, holding her hand and placing a foot on her foot.[44] Guest visitors also attended some of the séances; the Feilding report mentions that Professor Bottazzi and Professor Galeotti were present at the fourth séance, and a Mr. Ryan was present at the eighth séance.[44]

Although the investigators caught Palladino cheating, they were convinced Palladino produced genuine supernatural phenomena such as levitations of the table, movement of the curtains, movement of objects from behind the curtain and touches from hands.[44] Regarding the first report by Carrington and Feilding, the American scientist and philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce wrote:

Eusapia Palladino has been proved to be a very clever prestigiateuse and cheat, and was visited by a Mr. Carrington.... In point of fact he has often caught the Palladino creature in acts of fraud. Some of her performances, however, he cannot explain; and thereupon he urges the theory that these are supernatural, or, as he prefers it "supernormal." Well, I know how it is that when a man has been long intensely exercised and over fatigued by an enigma, his common-sense will sometimes desert him; but it seems to me that the Palladino has simply been too clever for him.... I think it more plausible that there are tricks that can deceive Mr. Carrington.[45]

Frank Podmore in his book The Newer Spiritualism (1910) wrote a comprehensive critique of the Feilding report. Podmore said that the report provided insufficient information for crucial moments and the investigators representation of the witness accounts contained contradictions and inconsistencies as to who was holding Palladino's feet and hands.[44] Podmore found accounts among the investigators conflicted as to who they claimed to have observed the incident. Podmore wrote that the report "at almost every point leaves obvious loopholes for trickery."[44] During the séances the long black curtains were often intermixed with Palladino's long black dress. Palladino told Professor Bottazzi the black curtains were "indispensable." Researchers have suspected Palladino used the curtain to conceal her feet.[46]

The psychologist C. E. M. Hansel criticized the Feilding report based on the conditions of the séances being susceptible to trickery. Hansel said that they were performed in semi-dark conditions, held in the late night or early morning introducing the possibility of fatigue and the "investigators had a strong belief in the supernatural, hence they would be emotionally involved."[47]

In 1910, Everard Feilding returned to Naples, without Hereward Carrington and W. W. Baggally. Instead, he was accompanied by his friend, William S. Marriott, a magician of some distinction who had exposed psychic fraud in Pearson's Magazine.[48] His plan was to repeat the famous earlier 1908 Naples sittings with Palladino. Unlike the 1908 sittings which had baffled the investigators, this time Feilding and Marriott detected her cheating, just as she had done in the US.[49] Her deceptions were obvious. Palladino evaded control and was caught moving objects with her foot, shaking the curtain with her hands, moving the cabinet table with her elbow and touching the séance sitters. Milbourne Christopher wrote regarding the exposure "when one knows how a feat can be done and what to look for, only the most skillful performer can maintain the illusion in the face of such informed scrutiny."[49]

In 1992, Richard Wiseman analyzed the Feilding report of Palladino and argued that she employed a secret accomplice that could enter the room by a fake door panel positioned near the séance cabinet. Wiseman discovered this trick was already mentioned in a book from 1851, he also visited a carpenter and skilled magician who constructed a door within an hour with a false panel. The accomplice was suspected to be her second husband, who insisted on bringing Palladino to the hotel where the séances took place.[50] Paul Kurtz suggested that Carrington could have been Palladino's secret accomplice. Kurtz found it suspicious that he was appointed as her manager after the séances in Naples. Carrington was also absent on the night of the last séance.[51] However, Massimo Polidoro and Gian Marco Rinaldi who analyzed the Feilding report came to the conclusion that no secret accomplice was needed as Palladino during the 1908 Naples séances could have produced the phenomena by using her foot.[52]

America

Palladino visited America in 1909 with Hereward Carrington as her manager.[9] Her arrival was publicized by the American press, with newspapers such as the New York Times and magazines such as the Cosmopolitan publishing numerous articles on the Italian medium.[53]

The magician Howard Thurston attended a séance and endorsed Palladino's levitation of a table as genuine.[6] However, at a séance on 18 December in New York, the Harvard psychologist Hugo Münsterberg with the help of a hidden man lying under a table, caught her levitating the table with her foot.[9] He had also observed Palladino free her foot from her shoe and use her toes to move a guitar in the séance cabinet.[4] Münsterberg also claimed that Palladino moved the curtains from a distance in the room by releasing a jet of air from a rubber bulb that she had in her hand.[54][55] Daniel Cohen said that "[Palladino] was undaunted by Munsterberg's exposure. Her tricks had been exposed many times before, yet she had prospered."[56] The exposure was not taken seriously by Palladino's defenders.[57]

In January, 1910 a series of séance sittings were held at the physics laboratory at Columbia University. Scientists such as Robert W. Wood and Edmund Beecher Wilson attended. The magicians W. S. Davis, J. L. Kellogg, J. W. Sargent and Joseph Rinn were present in the last séance sittings in April. They discovered that Palladino had freed her left foot to perform the phenomena. Rinn gave a full account of fraudulent behavior observed in a séance of Palladino.[9] Milbourne Christopher summarized the exposure:

Joseph F. Rinn and Warner C. Pyne, clad in black coveralls, had crawled into the dining room of Columbia professor Herbert G. Lord's house while a Palladino seance was in progress. Positioning themselves under the table, they saw the medium's foot strike a table leg to produce raps. As the table tilted to the right, due to pressure of her right hand on the surface, they saw her put her left foot under the left table leg. Pressing down on the tabletop with her left hand and up with her left foot under the table leg to form a clamp, she lifted her foot and "levitated" the table from the floor.[58]

Palladino was offered $1000 by Rinn if she could perform a feat in controlled conditions that could not be duplicated by magicians. Palladino eventually agreed to the contest but did not turn up for it, and instead returned to Italy.[9]

Tricks

In England, America, France and Germany, Palladino had been caught utilizing tricks.[3][4][5][10] Psychical researchers such as Hereward Carrington who believed some of her phenomena to be genuine, accepted that she would resort to trickery on occasion.[59]

Historian Peter Lamont has written that although Palladino's defenders accepted that she would cheat, they "pointed to the best evidence (where, they argued, fraud had been impossible), [but] critics argued that the investigators had simply missed it."[60] On the subject of fraud and Palladino, the philosopher and skeptic Paul Kurtz wrote:

[Palladino] was caught red-handed in blatant acts of fraud by members of the Society for Psychical Research in Cambridge and by scientific teams at Columbia and Harvard Universities. She was shown to be substituting her hand or foot and using them in darkened seances to move objects so that they appeared to be levitating. Even her defenders conceded that she cheated, at least some of the time. The problem that puzzles me is this; If one finds sleight-of-hand techniques being used some of the time by such individuals, then why should one accept anything else that is presented by them as genuine?... Skeptics question the first Feilding report because in a subsequent test by Feilding and other tests by scientists, Palladino had been caught cheating.[61]

In 1910, Stanley LeFevre Krebs wrote an entire book debunking Palladino and exposing the tricks she had used throughout her career, Trick Methods of Eusapia Paladino.[62] The psychologist Joseph Jastrow's book The Psychology of Conviction (1918), included a chapter ("The Case of Paladino (sic)") exposing Palladino's tricks.[3]

Magicians such as Harry Houdini and Joseph Rinn have claimed all her feats were conjuring tricks.[7][8] According to Houdini "Palladino cheated at Cambridge, she cheated in l'Aguélas, and she cheated in New York and yet each time that she was caught cheating the Spiritualists upheld her, excused her, and forgave her. Truly their logic sometimes borders on the humorous."[7]

John Mulholland stated that "Palladino was caught cheating times without number even by those who believed in her, and she made no bones about admitting it."[63] Researchers have suspected that Palladino's first husband, a travelling conjuror, taught her séance tricks.[4][14] The magician Milbourne Christopher demonstrated Palladino's fraudulent techniques in his stage performances and on Johnny Carson's "Tonight Show".[6]

Palladino dictated the lighting and "controls" that were to be used in her mediumistic séances. The fingertips of her right hand rested upon the back of the hand of one "controller." Her left hand was grasped at the wrist by a second controller seated on her other side. Her feet rested on top of the feet of her controllers, sometimes beneath them. A controller's foot was in contact with only the toe of her shoe. Occasionally her ankles were tied to the legs of her chair, but they were given a play of four inches. During the sitting in semi-darkness, her ankles would become free. Generally she was unbound. In one instance, a controller cut her free so that phenomena might occur.[10][64]

Theodor Lipps who attended a séance sitting in 1898 in Munich noticed that, instead of Palladino's hand, he held the hand of the sitter controlling the left side of the medium. In this way Palladino had freed both hands. She was also discovered using trickery by others in Germany.[57] Max Dessoir and Albert Moll of Berlin detected the precise substitution tricks that were used by Palladino. Dessoir and Moll wrote: "The main point is cleverly to distract attention and to release one or both hands or one or both feet. This is Paladino's chief trick".[65]

Palladino normally refused to allow someone beneath the table to hold her feet with his hands. She refused to levitate the table from a standing position. The table being rectangular, she had to sit only at a short side. No wall of any kind could stand between Palladino and the table. The weight of the table was seventeen pounds. The table levitated to a height of 3 to 10 inches for a maximum of 2–3 seconds.[66] She was an expert at freeing a hand or foot to produce phenomena. She chose to sit at the short side of the table so that her controllers on each side had to sit closer together, making it easier to deceive them.[3]

Her levitation of a table began by freeing one foot, rocking the table, and then slipping her toe under one leg. Since she sat at the narrow end of the table, this was made possible.[6] She lifted the table by rocking back on the heel of this foot. She made the "spirit" raps by striking a leg of the table with a free foot.[6]

A photograph, taken in the dark, of a small stool that was alleged to have levitated was revealed to be sitting on Palladino's head. After she saw this photo, the stool remained immobile on the floor. A plaster impression taken of a spirit hand matched Palladino's hand. She was caught using a hair to move a scale. In the dim light, her fist, wrapped in a handkerchief, became a materialized spirit.[66]

Science historian Sherrie Lynne Lyons wrote that the glowing or light-emitting hands in séances could easily be explained by the rubbing of oil of phosphorus on the hands.[67] In 1909 an article was published in The New York Times titled "Paladino Used Phosphorus". Hereward Carrington confessed to having painted Palladino's arm with phosphorescent paint, though he claimed to have used the paint to detect fraud by tracking the movement of her arm. There was publicity over the incident and Carrington claimed his comments had been misquoted by newspapers.[68]

The conjuror W. S. Davis published an article (with diagrams) exposing the tricks of Palladino. Davis also speculated that she used a piece of wire that she hid in her dress to tilt the séance table. Davis noted that when an attempt had been made to place a screen between her and the table she protested. Davis wrote she could not lift the table unless her dress was in contact with it and there is no obstruction between herself and the table.[69] Physician Leonard Keene Hirshberg who attended a séance, observed Palladino to have "hook[ed] her skirt and foot into a tiny reed table behind her" he also said that he heard a noise that sounded like "a piece of wire, pin, or toe-nail groping its way under the table."[70]

The psychologist Millais Culpin wrote that Palladino was a conscious cheat but also had symptoms of hysterical dissociation so may have deceived herself.[71] Laura Finch, editor of the Annals of Psychical Science, wrote in 1909 that Palladino had "erotic tendencies" and some of her male séance sitters were deluded or "glamoured" by her presence.[72] According to Deborah Blum, Palladino had a habit of "climbing into the laps of the male" investigators.[73]

M. Lamar Keene said that "observers said that Eusapia Palladino used to experience obvious orgasmic reactions during her séances and had a marked propensity for handsome male sitters."[74] In 1910, Palladino admitted to an American reporter that she cheated in her séances, claiming her sitters had 'willed' her to do so.[75] Eric Dingwall who investigated the mediumship of Palladino came to the conclusion that she was "vital, vulgar, amorous and a cheat."[76]

See also

- Mina Crandon

- Albert de Rochas, leading French psychic researcher and one of the committee members who investigated Palladino.

Notes

- ↑ Georgess McHargue. (1972). Facts, Frauds, and Phantasms: A Survey of the Spiritualist Movement. Doubleday. p. 136. ISBN 978-0385053051

- ↑ Rosemary Ellen Guiley. (1994). The Guinness Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits. Guinness Publishing. p. 242. ISBN 978-0851127484

- 1 2 3 4 Joseph Jastrow. (1918). The Psychology of Conviction. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 101–127:

The 1918 chapter was a re-print of an article that Jastrow had written in 1910: Jastrow, Joseph, "The Case of Paladino (sic)", The American Review of Reviews, Vol.42, No.1, (July 1910), pp.74—84. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Walter Mann. (1919). The Follies and Frauds of Spiritualism. Rationalist Association. London: Watts & Co. pp. 115–130

- 1 2 Ernest Hilgard. (1967). Introduction to Psychology. Harcourt, Brace and Company. p. 243. ISBN 978-0155436381 "Eusapia Palladino was a medium who was able to make a table move and produce other effects, such as tapping sounds, by the aid of a "spirit" called John King. Investigated repeatedly between 1893 and 1910, she convinced many distinguished scientists of her powers, including the distinguished Italian criminologist Lombroso and the British physicist Sir Oliver Lodge. She was caught in deceptive trickery as early as 1895, and the results were published. Yet believers continued to support her genuineness, as some do today, even though in an American investigation in 1910, her trickery was abundantly exposed. Two investigators, dressed in black, crawled under the table unobserved and were able to see exactly how she used her foot to create the 'supernatural' phenomena."

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Milbourne Christopher. (1971). ESP, Seers & Psychics. Crowell. pp. 188–204. ISBN 978-0690268157

- 1 2 3 Harry Houdini. (2011, originally published in 1924). A Magician Among the Spirits. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–65. ISBN 978-1108027489

- 1 2 Joseph Rinn. (1950). Sixty Years of Psychical Research: Houdini and I Among the Spiritualists. Truth Seeker Company. pp. 272–356

- 1 2 3 4 5 C. E. M. Hansel. (1980). ESP and Parapsychology: A Critical Re-Evaluation. Prometheus Books. pp. 58–64. ISBN 978-0879751197

- 1 2 3 4 Massimo Polidoro. (2003). Secrets of the Psychics: Investigating Paranormal Claims. Prometheus Books. pp. 62–96. ISBN 978-1591020868

- ↑ Paul Kurtz. (1985). A Skeptic's Handbook of Parapsychology. Prometheus Books. p. 196. ISBN 0-87975-300-5

- ↑ M. Brady Brower. (2010). Unruly Spirits: The Science of Psychic Phenomena in Modern France. University of Illinois Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-252-03564-7

- ↑ Baron Johan Liljencrants. (1918). Spiritism and Religion: A Moral Study. Catholic University of America. p. 39

- 1 2 D. H. Rawcliffe. (1988). Occult and Supernatural Phenomena. Dover Publications. p. 321

- ↑ Henry-Louis de La Grange. (2008). Gustav Mahler: A New Life Cut Short (1907–1911). Oxford University Press. p. 610. ISBN 978-0198163879

- ↑ Krystyna Tokarzówna and Stanisław Fita, Bolesław Prus, pp. 440, 443, 445–53.

- ↑ Leslie Shepard. (1991). Encyclopedia of Occultism & Parapsychology. Gale Research Company. p. 1209. ISBN 978-0810301962

- ↑ Krystyna Tokarzówna and Stanisław Fita, Bolesław Prus, p. 448.

- ↑ Krystyna Tokarzówna and Stanisław Fita, Bolesław Prus, p. 521.

- 1 2 Joseph McCabe. (1920). Is Spiritualism Based On Fraud? The Evidence Given By Sir A. C. Doyle and Others Drastically Examined. London, Watts & Co. p. 14

- 1 2 M. Brady Brower. (2010). Unruly Spirits: The Science of Psychic Phenomena in Modern France. University of Illinois Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0252077517

- ↑ Leonard Zusne; Warren H. Jones. (2014). Anomalistic Psychology: A Study of Magical Thinking. Psychology Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-805-80508-6 "In spite of overwhelming evidence that pointed to fraud, such as was found in the case of the notorious Neapolitan medium Eusapia Palladino, Sir Oliver Lodge, another English physicist, refused to change his favorable opinion of her."

- ↑ Ruth Brandon. (1983). The Spiritualists: The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 258–259. ISBN 0-297-78249-5

- 1 2 The British Medical Journal. (Nov. 9, 1895). Exit Eusapia!. Volume. 2, No. 1819. p. 1182.

- 1 2 The British Medical Journal. (Nov. 16, 1895). Exit Eusapia. Volume 2, No. 1820. pp. 1263–1264.

- 1 2 Janet Oppenheim. (1985). The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850–1914. Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0521265058

- ↑ Massimo Polidoro. (2003). Secrets of the Psychics: Investigating Paranormal Claims. Prometheus Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-1591020868

- ↑ Harry Price, Fifty Years of Psychical Research, chapter XI: The Mechanics of Spiritualism, F&W Media International, Ltd, 2012.

- ↑ Camille Flammarion. (1909). Mysterious Psychic Forces. Small, Maynard and Company. pp. 63–135

- ↑ Joseph McCabe. (1920). Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud?: The Evidence Given By Sir A. C. Doyle and Others Drastically Examined. London, Watts & Co. p. 57. "The impressions of faces which she got in wax or putty were always her face. I have seen many of them. The strong bones of her face impress deep. Her nose is relatively flattened by the pressure. The hair on the temples is plain. It is outrageous for scientific men to think that either "John King" or an abnormal power of the medium made a human face (in a few minutes) with bones and muscles and hair, and precisely the same bones and muscles and hair as those of Eusapia. I have seen dozens of photographs of her levitating a table. On not a single one are her person and dress entirely clear of the table."

- ↑ C. E. M. Hansel. (1980). ESP and Parapsychology: A Critical Re-Evaluation. Prometheus Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-0879751197 "These experiments extended over three years at a cost of 25,000 francs. They were attended by the great French scientists Pierre and Marie Curie, D'Arsonval, the physicist; Henri Bergson, the philosopher; Richet the physiologist; and numerous other scientists and savants. The French committee detected many signs of trickery on Eusapia's part, but they were clearly puzzled by some of the phenomena."

- 1 2 Barbara Goldsmith. (2005). Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie. W. W. Norton. p. 138. ISBN 978-0739453056

- 1 2 3 4 Susan Quinn. (1995). Marie Curie: A Life. Simon and Schuster. pp. 208–226. ISBN 0-671-67542-7

- ↑ Joseph McCabe. (1920). Spiritualism: A Popular History From 1847. T. F. Unwin Ltd. p. 210

- ↑ Sofie Lachapelle. (2011). Investigating the Supernatural: From Spiritism and Occultism to Psychical Research and Metapsychics in France, 1853–1931. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1421400136

- ↑ C. E. M. Hansel. (1980). ESP and Parapsychology: A Critical Re-Evaluation. Prometheus Books. p. 59. ISBN 978-0879751197 "Eusapia was introduced to Lombroso in 1888, and, by 1891, she had convinced him of her supernatural powers. This, it should be noted, need not have presented her with as much difficulty as might appear. Lombroso was no hidebound skeptic. In 1882, he had reported the case of a patient who, having lost the power of seeing with her eyes, saw as clearly as before with the aid of the tip of her nose and the lobe of her left ear."

- ↑ Graus, Andrea (2016). "Discovering Palladino's mediumship. Otero Acevedo, Lombroso and the quest for authority". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 52 (3): 211–230. doi:10.1002/jhbs.21789. hdl:10067/1344840151162165141. PMID 27122382.

- ↑ Natale, Simone (2016). Supernatural Entertainments: Victorian Spiritualism and the Rise of Modern Media Culture. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 96–98. ISBN 978-0-271-07104-6.

- ↑ Cesare Lombroso. (1909). After Death — What?. Small, Maynard & Company Publishers. p. 49

- ↑ William Kalush, Larry Sloman. (2006). The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America's First Superhero. Atria Books. p. 419. ISBN 978-0743272087 "The most notorious medium who used her sexual charms to seduce her scientific investigators was Eusapia Palladino... [She] had no qualms about sleeping with her sitters; among them were the eminent criminologist Lombroso and the Nobel Prize—winning French physiologist Charles Richet. After being discredited, Palladino's career was revived in 1909 when Hereward Carrington, acting as her manager, brought her to the United States."

- ↑ Joseph McCabe. (1920). Scientific Men and Spiritualism: A Skeptic's Analysis. The Living Age. June 12. pp. 652–657.

- ↑ Brancaccio, Maria Teresa. (2014). Enrico Morselli's Psychology and "Spiritism": Psychiatry, psychology and psychical research in Italy in the decades around 1900. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 48: 75–84.

- ↑ Alfred Douglas. (1982). Extra-Sensory Powers: A Century of Psychical Research. Overlook Press. p. 98

- 1 2 3 4 5 Frank Podmore. (1910). The Newer Spiritualism. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 114–44

- ↑ Justus Buchler. (2000). The Philosophy of Peirce: Selected Writings, Volume 2. Indiana University Press. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0253211903

- ↑ Gordon Stein. (1996). The Encyclopedia of the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. p. 490. ISBN 978-1573920216

- ↑ C. E. M. Hansel. (1980). ESP and Parapsychology: A Critical Re-Evaluation. Prometheus Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-0879751197

- ↑ Massimo Polidoro. (2001). Final Séance: The Strange Friendship Between Houdini and Conan Doyle. Prometheus Books. p. 91. ISBN 978-1573928960 "William S. Marriott was a London professional magician who performed under the name of "Dr. Wilmar" and who, for some time, interested himself in Spiritualism. In 1910 he had been asked by the SPR to take part in a series of sittings with the Italian medium Eusapia Palladino, and had concluded that all he had seen could be attributed to fakery. That same year he published four articles for Pearson's magazine in which he detailed and duplicated in photographs various tricks of self-claimed psychics and mediums."

- 1 2 Milbourne Christopher. (1971). ESP, Seers & Psychics. Crowell. p. 201. ISBN 978-0690268157

- Everard Feilding, William S. Marriott. (1910). Report on Further Series of Sittings with Eusapia Palladino at Naples. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 15: 20–32.

- ↑ Richard Wiseman. (1997). Chapter 3 The Feilding Report: A Reconsideration. In Deception and Self-Deception: Investigating Psychics. Prometheus Press. ISBN 1-57392-121-1

- ↑ Paul Kurtz. (1985). Spiritualists, Mediums and Psychics: Some Evidence of Fraud. In Paul Kurtz (ed.). A Skeptic's Handbook of Parapsychology. Prometheus Books. pp. 177–223. ISBN 978-0879753009

- ↑ Massimo Polidoro. (2003). Secrets of the Psychics: Investigating Paranormal Claims. Prometheus Books. pp. 65–95. ISBN 978-1591020868

- ↑ Natale, Simone (2016). Supernatural Entertainments: Victorian Spiritualism and the Rise of Modern Media Culture. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 92–105. ISBN 978-0-271-07104-6.

- ↑ William Seabrook. (1941). Wood as a Debunker of Scientific Cranks and Frauds — and His War with the Mediums. In Doctor Wood. Harcourt, Brace and Co.

- ↑ Fakebusters II: Scientific Detection of Fakery in Art and Philately

- ↑ Daniel Cohen. (1972). In Search of Ghosts. Dodd, Mead & Company. p. 109. ISBN 978-0396064855

- 1 2 Albert von Schrenck-Notzing. (1923). Phenomena of Materialisation. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. pp. 8–10

- ↑ Milbourne Christopher. (1979). Search for the Soul. Crowell. p. 47. ISBN 978-0690017601

- ↑ Hereward Carrington. (1909). Eusapia Palladino and Her Phenomena. New York: B. W. Dodge. pp. 327–328

- ↑ Peter Lamont. (2013). Extraordinary Beliefs: A Historical Approach to a Psychological Problem. Cambridge University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-1107688025 "Palladino was no simple case: on the one hand, she was regularly caught cheating, even by those who continued to express belief; on the other hand, she was reported to have produced genuine phenomena at times, in front of experienced and (previously) sceptical observers. For proponents, she was another example of the genuine but fraudulent demonstrator of extraordinary phenomena... Critics pointed to evidence of fraud, proponents pointed to the best evidence (where, they argued, fraud had been impossible), and critics argued that the investigators had simply missed it."

- ↑ Vern L. Bullough; Timothy J. Madigan. (1994). Toward a New Enlightenment: The Philosophy of Paul Kurtz. Transaction Publishers. p. 159. ISBN 978-1560001188

- ↑ Stanley LeFevre Krebs. (1910). Trick Methods of Eusapia Paladino.

- ↑ John Mulholland. (1938). Beware Familiar Spirits. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 127. ISBN 978-1111354879

- ↑ Ruth Brandon. (1983). The Spiritualists: The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0394527406

- ↑ Joseph Jastrow. (1918). The Psychology of Conviction. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 100–111. "Both Dr. Moll and Dr. Dessoir, of Berlin, detected the precise substitution-tricks that were used in New York. The main point is cleverly to distract attention and to release one or both hands or one or both feet. This is Paladino's chief trick. Dr. Moll records the throwing out of the curtain to cover the hand substitution; and notes that, by watching for it, he could detect the exact moment when the hand or foot was freed."

- 1 2 Frank Podmore. (1910). The Newer Spiritualism. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 87–113

- ↑ Sherrie Lynne Lyons. (2010). Species, Serpents, Spirits, and Skulls: Science at the Margins in the Victorian Age. State University of New York Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-1438427980

- ↑ The New York Times. Paladino Used Phosphorus. November 19, 1909.

- ↑ The New York Times. (1909). Sidelights on the Paladino Delusion. November 21.

- ↑ Hirshberg, Leonard Keene. (1910). The Case Against Madame Eusapia Palladino. The Medical Critic and Guide 13: 163–168.

- ↑ Millais Culpin. (1920). Spiritualism and the New Psychology: An Explanation of Spiritualist Phenomena and Beliefs in Terms of Modern Knowledge. Edward Arnold, London. pp. 143–149

- ↑ Baron Johan Liljencrants. (1918). Spiritism and Religion. "Can you talk to the dead?". Devin-Adair Publishing Company. p. 40

- ↑ Deborah Blum. (2007). Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0143038955

- ↑ M. Lamar Keene. (1997). The Psychic Mafia. Prometheus Books. p. 74. ISBN 978-1573921619

- ↑ Ronald Pearsall. (1972). The Table-Rappers. Book Club Associates. p. 224

- ↑ David C. Knight. (1969). The ESP Reader. Grosset & Dunlap. p. 60

References

- Ruth Brandon. (1983). The Spiritualists: The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Hereward Carrington. (1907). The Physical Phenomena of Spiritualism. Herbert B. Turner & Co.

- Hereward Carrington. (1909). Eusapia Palladino and Her Phenomena. B.W. Dodge & Company. Carrington's detailed descriptions and analysis of experiments conducted in European cities between 1891 and 1908.

- Hereward Carrington. (1909). Eusapia Palladino: The Despair of Science. McClure's Magazine 33: 660–675.

- Edward Clodd. (1917). The Question: A Brief History and Examination of Modern Spiritualism. Grant Richards, London.

- Millais Culpin. (1920). Spiritualism and the New Psychology: An Explanation of Spiritualist Phenomena and Beliefs in Terms of Modern Knowledge. Edward Arnold, London.

- W. S. Davis. (1909). Sidelights on the Paladino Delusion. The New York Times. November 21.

- W. S. Davis. (1909). An Analysis of the Exploits of Madame Paladino. The New York Times. October 17.

- W. S. Davis. (1910). The New York Exposure of Eusapia Palladino. Journal of the American Society of Psychical Research 4: 401–424.

- Francesco Paolo de Ceglia, Lorenzo Leporiere. (2019). "La pitonessa, il pirata e l'acuto osservatore. Spiritismo e scienza nell'Italia della belle époque". Editrice Bibliografica, 2018.

- Everard Feilding; W. W. Baggally; Hereward Carrington. (1909). Report on a Series of Sittings with Eusapia Palladino. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 23: 309–569.

- Everard Feilding; William S. Marriott. (1910). Report on Further Series of Sittings with Eusapia Palladino at Naples. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 15: 20–32.

- Everard Feilding. (1963). Sittings with Eusapia Palladino & Other Studies. University Books.

- Barbara Goldsmith. (2005). Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-05137-4

- Nandor Fodor. (1934). An Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science. Arthurs Press.

- C. E. M. Hansel. (1980). ESP and Parapsychology: A Critical Re-Evaluation. Prometheus Books.

- Ernest Abraham Hart. (1896). Hypnotism, Mesmerism and the New Witchcraft. Smith, Elder & Co. (Reproduces the British Medical Journal article and letters on Palladino).

- Harry Houdini. (2011, originally published in 1924). A Magician Among the Spirits. Cambridge University Press.

- Joseph Jastrow. (1910). The Case of Eusapia Palladino. Review of Reviews 41: 74–84.

- Joseph Jastrow. (1910). The Unmasking of Paladino. An Actual Observation of the Complete Machinery of the Famous Italian Medium. Collier’s Weekly. 14 May.

- Joseph Jastrow. (1918). The Psychology of Conviction: A Study of Beliefs and Attitudes. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Joseph Jastrow. (1935). Wish and Wisdom: Episodes in the Vagaries of Belief. D. Appleton-Century Co. Chapter 12 "Paladino's Table" contains a photo of a mysterious spirit face in clay, compared to Palladino's face. The similarity is striking.

- Stanley LeFevre Krebs. (1910) Trick Methods of Eusapia Paladino. Philadelphia. Very informative and critical explanations.

- Paul Kurtz. (1985). A Skeptic's Handbook of Parapsychology. Prometheus Books.

- James H. Leuba. (1909). Eusapia Palladino: A Critical Consideration of the Medium's Most Striking Performances. Putnam's Magazine 7: 407–415.

- Walter Mann. (1919). The Follies and Frauds of Spiritualism. Rationalist Association. London: Watts & Co.

- Joseph McCabe. (1920). Scientific Men and Spiritualism: A Skeptic's Analysis. The Living Age. June 12. pp. 652–657.

- Joseph McCabe. (1920). Is Spiritualism Based On Fraud? The Evidence Given By Sir A. C. Doyle and Others Drastically Examined. London: Watts & Co.

- Georgess McHargue. (1972). Facts, Frauds, and Phantasms: A Survey of the Spiritualist Movement. Doubleday.

- John Mulholland. (1938). Beware Familiar Spirits. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Hugo Münsterberg. (1910). My Friends the Spiritualists: Some Theories and Conclusions Concerning Eusapia Palladino. Metropolitan Magazine 31: 559–572.

- Simone Natale. (2016) Supernatural Entertainments: Victorian Spiritualism and the Rise of Modern Media Culture. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-07104-6.

- Frank Podmore. (1910). The Newer Spiritualism. Chapters 3 "Eusapia Palladino" and 4 "Eusapia Palladino and the S.P.R." Henry Holt and Company.

- Massimo Polidoro. (2003). Secrets of the Psychics: Investigating Paranormal Claims. Prometheus Books.

- Harry Price and Eric J. Dingwall, Revelations of a Spirit Medium, Arno Press, 1975 (reprint of the 1891 edition by Charles F. Pidgeon). This extremely rare, forgotten book gives an "insider's knowledge" of 19th-century deceptions.

- Julien Proskauer. (1946). The Dead Do Not Talk. Harper & Brothers. pp. 119–121. (Discusses Palladino and her fraudulent levitation techniques).

- Susan Quinn. (1995). Marie Curie: A Life. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-67542-7

- D. H. Rawcliffe. (1988, originally published in 1952). Occult and Supernatural Phenomena. Chapter 21: "Eusapia Palladino". Dover Publications.

- Joseph Rinn. (1950). Sixty Years of Psychical Research: Houdini and I Among the Spiritualists. Truth Seeker Company.

- Andreas Sommer. (2012). Psychical research and the origins of American psychology: Hugo Munsterberg, William James and Eusapia Palladino. History of the Human Sciences. Vol 2: 23–44.

- Krystyna Tokarzówna and Stanisław Fita, Bolesław Prus, 1847–1912: Kalendarz życia i twórczości (Bolesław Prus, 1847–1912: a Calendar of [His] Life and Work), edited by Zygmunt Szweykowski, Warsaw, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1969.

- Richard Wiseman. (1997). Deception & Self-Deception: Investigating Psychics. Prometheus Books.

- Wood, Robert W. (1910). Report of an Investigation of the Phenomena Connected with Eusapia Palladino. Science 31 (803): 776–780.