| Führerbunker | |

|---|---|

Führer's bunker | |

July 1947 photo of the rear entrance to the Führerbunker in the garden of the Reich Chancellery. The bodies of Hitler and Eva Braun were burned in a shell hole in front of the emergency exit at left; the cone-shaped structure in the centre served for ventilation, and as a bomb shelter for the guards.[1] | |

| |

| General information | |

| Town or city | Berlin |

| Country | Nazi Germany |

| Coordinates | 52°30′45″N 13°22′53″E / 52.5125°N 13.3815°E |

| Construction started | 1943 |

| Completed | 23 October 1944 |

| Destroyed | 5 December 1947 |

| Cost | 1.35 million ℛ︁ℳ︁ (equivalent to €5 million in 2021) |

| Owner | Nazi Germany |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Albert Speer, Karl Piepenburg |

| Architecture firm | Hochtief AG |

The Führerbunker (German pronunciation: [ˈfyːʁɐˌbʊŋkɐ] ⓘ) was an air raid shelter located near the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, Germany. It was part of a subterranean bunker complex constructed in two phases in 1936 and 1944. It was the last of the Führer Headquarters (Führerhauptquartiere) used by Adolf Hitler during World War II.

Hitler took up residence in the Führerbunker on 16 January 1945, and it became the centre of the Nazi regime until the last week of World War II in Europe. Hitler married Eva Braun there on 29 April 1945, less than 40 hours before they committed suicide.

After the war, both the old and new Chancellery buildings were levelled by the Soviets. The underground complex remained largely undisturbed until 1988–89, despite some attempts at demolition. The excavated sections of the old bunker complex were mostly destroyed during reconstruction of that area of Berlin. The site remained unmarked until 2006, when a small plaque was installed with a schematic diagram. Some corridors of the bunker still exist but are sealed off from the public.

Construction

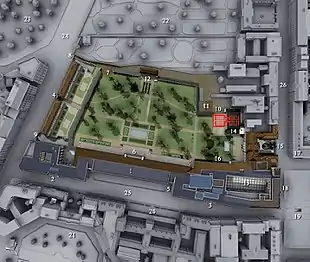

The Reich Chancellery bunker was initially constructed as a temporary air-raid shelter for Hitler, who actually spent very little time in the capital during most of the war. Increased bombing of Berlin led to expansion of the complex as an improvised permanent shelter. The elaborate complex consisted of two separate shelters, the Vorbunker ("forward bunker"; the upper bunker), completed in 1936, and the Führerbunker, located 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) lower than the Vorbunker and to the west-southwest, completed in 1944.[2][3] They were connected by a stairway set at right angles and could be closed off from each other by a bulkhead and steel door.[4] The Vorbunker was located 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) beneath the cellar of a large reception hall behind the old Reich Chancellery at Wilhelmstrasse 77.[5] The Führerbunker was located about 8.5 m (28 ft) beneath the garden of the old Reich Chancellery, 120 m (390 ft) north of the new Reich Chancellery building at Voßstraße 6.[6] Besides being deeper under ground, the Führerbunker had significantly more reinforcement. Its roof was made of concrete almost 3 m (9 ft 10 in) thick.[7] About 30 small rooms were protected by approximately 4 m (13 ft 1 in) of concrete; exits led into the main buildings, as well as an emergency exit up to the garden. The Führerbunker development was built by the Hochtief company as part of an extensive programme of subterranean construction in Berlin begun in 1940.[8]

Hitler's accommodations were in this newer, lower section, and by February 1945 it had been decorated with high-quality furniture taken from the Chancellery, along with several framed oil paintings.[9] After descending the stairs into the lower section and passing through the steel door, there was a long corridor with a series of rooms on each side.[10] On the right side were a series of rooms which included generator/ventilation rooms and the telephone switchboard.[10] On the left side was Eva Braun's bedroom/sitting room (also known as Hitler's private guest room), an antechamber (also known as Hitler's sitting room), which led into Hitler's study/office.[11][12] On the wall hung a large portrait of Frederick the Great, one of Hitler's heroes.[13] A door led into Hitler's modestly furnished bedroom.[12] Next to it was the conference/map room (also known as the briefing/situation room) which had a door that led out into the waiting room/anteroom.[11][12]

The bunker complex was self-contained.[14] However, as the Führerbunker was below the water table, conditions were unpleasantly damp, with pumps running continuously to remove groundwater. A diesel generator provided electricity, and well water was pumped in as the water supply.[15] Communications systems included a telex, a telephone switchboard, and an army radio set with an outdoor antenna. As conditions deteriorated at the end of the war, Hitler received much of his war news from BBC radio broadcasts and via courier.[16]

End of World War II

Hitler moved into the Führerbunker on 16 January 1945, joined by his senior staff, including Martin Bormann. Eva Braun and Joseph Goebbels joined them in April, while Magda Goebbels and their six children took residence in the upper Vorbunker.[17] Two or three dozen support, medical, and administrative staff were also sheltered there. These included Hitler's secretaries (including Traudl Junge), a nurse named Erna Flegel, and Sergeant Rochus Misch, who was both bodyguard and telephone switchboard operator. Initially, Hitler continued to use the undamaged wing of the Reich Chancellery, where he held afternoon military conferences in his large study.[18] Afterwards, he would have tea with his secretaries before returning to the bunker complex for the night. After several weeks of this routine, Hitler seldom left the bunker except for short strolls in the chancellery garden with his dog Blondi.[18] The bunker was crowded, the atmosphere was oppressive, and air raids occurred daily.[19] Hitler mostly stayed on the lower level, where it was quieter and he could sleep.[20] Conferences took place for much of the night,[19] often until 05:00.[21]

On 16 April, the Red Army started the Battle of Berlin, and they started to encircle the city by 19 April.[22] Hitler made his last trip to the surface on 20 April, his 56th birthday, going to the ruined garden of the Reich Chancellery where he awarded the Iron Cross to boy soldiers of the Hitler Youth.[23] That afternoon, Berlin was bombarded by Soviet artillery for the first time.[24]

Hitler was in denial about the dire situation and placed his hopes on the units commanded by Waffen-SS General Felix Steiner, the Armeeabteilung Steiner ("Army Detachment Steiner"). On 21 April, Hitler ordered Steiner to attack the northern flank of the encircling Soviet salient and ordered the German Ninth Army, south-east of Berlin, to attack northward in a pincer attack.[25][26] That evening, Red Army tanks reached the outskirts of Berlin.[27] Hitler was told at his afternoon situation conference on 22 April that Steiner's forces had not moved, and he fell into a tearful rage when he realised that the attack was not going to be carried out. He openly declared for the first time the war was lost—and he blamed his generals. Hitler announced that he would stay in Berlin until the end and then shoot himself.[28]

On 23 April,[lower-alpha 1] Hitler appointed General of the Artillery Helmuth Weidling, commander of the LVI Panzer Corps, as the commander of the Berlin Defense Area, replacing Lieutenant-Colonel (Oberstleutnant) Ernst Kaether.[29] The Red Army had consolidated their investment of Berlin by 25 April, despite the commands being issued from the Führerbunker. There was no prospect that the German defence could do anything but delay the city's capture.[30] Hitler summoned Field Marshal Robert Ritter von Greim from Munich to Berlin to take over command of the Luftwaffe from Hermann Göring, and he arrived on 26 April along with his mistress, the test pilot Hanna Reitsch.[31]

On 28 April, Hitler learned that Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler was trying to discuss surrender terms with the Western Allies through Count Folke Bernadotte,[32] and Hitler considered this treason.[33] Himmler's SS representative in Berlin Hermann Fegelein was shot after being court-martialed for desertion, and Hitler ordered Himmler's arrest.[34][31] On the same day, General Hans Krebs made his last telephone call from the Führerbunker to Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of German Armed Forces High Command (OKW) in Fürstenberg. Krebs told him that all would be lost if relief did not arrive within 48 hours. Keitel promised to exert the utmost pressure on Generals Walther Wenck, commander of the Twelfth Army, and Theodor Busse, commander of the Ninth Army. Meanwhile, Bormann wired to German Admiral Karl Dönitz: "Reich Chancellery a heap of rubble."[31] He said that the foreign press was reporting fresh acts of treason and "that without exception Schörner, Wenck and the others must give evidence of their loyalty by the quickest relief of the Führer".[35]

That evening, von Greim and Reitsch flew out from Berlin in an Arado Ar 96 trainer. Field Marshal von Greim was ordered to get the Luftwaffe to attack the Soviet forces that had just reached Potsdamer Platz, only a city block from the Führerbunker.[lower-alpha 2][36][37] During the night of 28 April, General Wenck reported to Keitel that his Twelfth Army had been forced back along the entire front and it was no longer possible for his army to relieve Berlin.[38] Keitel gave Wenck permission to break off the attempt.[35]

Hitler married Eva Braun after midnight on 28–29 April in a small civil ceremony within the Führerbunker. He then took secretary Traudl Junge to another room and dictated his last will and testament.[39][lower-alpha 3] Hans Krebs, Wilhelm Burgdorf, Goebbels, and Bormann witnessed and signed the documents at approximately 04:00.[39] Hitler then retired to bed.[40]

Late in the evening of 29 April, Krebs contacted Jodl by radio: "Request immediate report. Firstly of the whereabouts of Wenck's spearheads. Secondly of time intended to attack. Thirdly of the location of the Ninth Army. Fourthly of the precise place in which the Ninth Army will break through. Fifthly of the whereabouts of General Rudolf Holste's spearhead."[38] In the early morning of 30 April, Jodl replied to Krebs: "Firstly, Wenck's spearhead bogged down south of Schwielow Lake. Secondly, Twelfth Army therefore unable to continue attack on Berlin. Thirdly, bulk of Ninth Army surrounded. Fourthly, Holste's Corps on the defensive."[38][41][42][lower-alpha 4]

SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke, commander of the centre government district of Berlin, informed Hitler during the morning of 30 April that he would be able to hold for less than two days. Later that morning, Weidling informed Hitler that the defenders would probably exhaust their ammunition that night and again asked him for permission to break out. Weidling finally received permission at about 13:00.[43] Hitler shot himself later that afternoon, at around 15:30, while Eva took cyanide.[44][45] In accordance with Hitler's instructions, his and Eva's bodies were burned in the garden behind the Reich Chancellery.[46] Goebbels became the new Head of Government and Chancellor of Germany (Reichskanzler) in accordance with Hitler's last will and testament. Reichskanzler Goebbels and Bormann sent a radio message to Dönitz at 03:15, informing him of Hitler's death, and that he was the new Head of State and President of Germany (Reichspräsident), in accordance with Hitler's last will and testament.[47]

Krebs talked to General Vasily Chuikov, commander of the Soviet 8th Guards Army, at about 04:00 on 1 May,[lower-alpha 5] and Chuikov demanded unconditional surrender of the remaining German forces. Krebs did not have the authority to surrender, so he returned to the bunker.[48] In the late afternoon, Goebbels had his children poisoned, and he and his wife left the bunker at around 20:30.[49] There are several different accounts on what followed. According to one account, Goebbels shot his wife and then himself. Another account was that they each bit on a cyanide ampule and were given a coup de grâce immediately afterwards.[50] Goebbels' SS adjutant Günther Schwägermann testified in 1948 that the couple walked ahead of him up the stairs and out to the Chancellery garden. He waited in the stairwell and heard the shots, then walked up the remaining stairs and saw the lifeless bodies of the couple outside. He then followed Joseph Goebbels' order and had an SS soldier fire several shots into Goebbels' body, which did not move.[49] The bodies were then doused with petrol and set alight, but the remains were only partially burned and not buried.[50]

Weidling had given the order for the survivors to break out to the northwest, and the plan got underway at around 23:00. The first group from the Reich Chancellery was led by Mohnke; they tried unsuccessfully to break through the Soviet rings and were captured the next day. Mohnke was interrogated by SMERSH, like others who were captured from the Führerbunker. The third breakout attempt from the Reich Chancellery was made around 01:00 on 2 May, and Bormann managed to cross the Spree. Artur Axmann followed the same route and reported seeing Bormann's body a short distance from the Weidendammer bridge.[51][lower-alpha 6]

At 01:00, the Soviet forces picked up a radio message from the LVI Panzer Corps requesting a cease-fire. Down in the Führerbunker, General Krebs and General Burgdorf committed suicide by gunshot to the head.[52] The last defenders in the area of the bunker complex were mainly made up of Frenchmen of the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne, others being Waffen-SS from the remnants of the 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nordland, Latvian SS and Spanish SS units.[53][54] A group of French SS remained in the area of the bunker until the early morning of 2 May.[55] The Soviet forces then captured the Reich Chancellery.[56] General Weidling surrendered with his staff at 6:00, and his meeting with Chuikov ended at 8:23.[38] Johannes Hentschel, the master electro-mechanic for the bunker complex, stayed after everyone else had either left or committed suicide, as the field hospital in the Reich Chancellery above needed power and water. He surrendered to the Red Army as they entered the bunker complex at 09:00 on 2 May.[57] The bodies of Goebbels' six children were discovered on 3 May. They were found in their beds in the Vorbunker with the clear mark of cyanide shown on their faces.[58]

Post-war events

The first post-war photos of the interior of the Führerbunker were taken in July 1945. On 4 July, American writer James P. O'Donnell toured the bunker after giving the Soviet guard a pack of cigarettes.[59][60] Many soldiers, politicians, and diplomats visited the bunker complex in the following days and months. Winston Churchill visited the Reich Chancellery and bunker on 14 July 1945.[61] On 11 December 1945, the Soviets allowed a limited investigation of the bunker grounds by the other Allied powers. Two representatives from each nation watched several Germans dig up soil; this included the site where Hitler's remains had been exhumed that May. Found during the dig were two hats identified as Hitler's, an undergarment with Braun's initials, and some reports to Hitler from Goebbels. The representatives planned to continue the work, but when they arrived the next morning, an NKVD armed guard met them and accused them of removing documents from the Chancellery. This was denied, but no further outside investigation was allowed until years later.[62]

The outer ruins of both Chancellery buildings were levelled by the Soviets between 1945 and 1949 as part of an effort to destroy the landmarks of Nazi Germany. A detailed interior site investigation by the Soviets, including measurements, took place on 16 May 1946.[63] Thereafter, the bunker largely survived, although some areas were partially flooded. In December 1947, the Soviets tried to blow up the bunker, but only the separation walls were damaged. In 1959, the East German government began a series of demolitions of the Chancellery, including the bunker.[64] Because it was near the Berlin Wall, the site was undeveloped and neglected until 1988–89.[65] During extensive construction of residential housing and other buildings on the site, work crews uncovered several underground sections of the old bunker complex; for the most part these were destroyed. Other parts of the Chancellery underground complex were uncovered, but these were ignored, filled in, or resealed.[66]

Government authorities wanted to destroy the last vestiges of these Nazi landmarks.[67] The construction of the buildings in the area around the Führerbunker was a strategy for ensuring the surroundings remained anonymous and unremarkable.[68] The emergency exit point for the Führerbunker (which had been in the Chancellery gardens) was occupied by a car park.[69]

On 8 June 2006, during the lead-up to the 2006 FIFA World Cup, an information board was installed to mark the location of the Führerbunker. The board, including a schematic diagram of the bunker, can be found at the corner of In den Ministergärten and Gertrud-Kolmar-Straße, two small streets about three minutes' walk from Potsdamer Platz. Rochus Misch, one of the last people living who was in the bunker at the time of Hitler's suicide, attended the ceremony.[70]

Ruins of the bunker after demolition in 1947

Ruins of the bunker after demolition in 1947 Site of Führerbunker and information board on Gertrud-Kolmar-Straße in October 2023

Site of Führerbunker and information board on Gertrud-Kolmar-Straße in October 2023 A side angle view of the site in July 2007

A side angle view of the site in July 2007

See also

- Berghof

- The Bunker – 1970 book

- The Bunker – 1981 film

- Downfall – 2004 film

- Matsushiro Underground Imperial Headquarters

- Nazi architecture

- Presidential Emergency Operations Center

- Stalin's bunker

- Wolf's Lair

References

Informational notes

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 286 states the appointment was 23 April; Hamilton 2008, p. 160 states "officially" it was the morning of 24 April; Dollinger 1997, p. 228, gives 26 April for the appointment.

- ↑ The Luftwaffe order differs in different sources. Beevor 2002, p. 342 states it was to attack Potsdamerplatz, but Ziemke states it was to support Wenck's Twelfth Army attack. Both agree that von Greim was also ordered to make sure Himmler was punished.

- ↑ "MI5 staff 2005: Hitler's will and marriage" on the website of MI5, using the sources available to Hugh Trevor-Roper (a World War II MI5 agent and historian/author of The Last Days of Hitler), records the marriage as taking place after Hitler had dictated his last will and testament.

- ↑ Dollinger 1997, p. 239, says Jodl replied, but Ziemke 1969, p. 120, and Beevor 2002, p. 537, say it was Keitel.

- ↑ Dollinger 1997, p. 239, states 03:00, and Beevor 2002, p. 367, 04:00, for Krebs' meeting with Chuikov.

- ↑ Ziemke 1969, p. 126 says that Weidling gave no orders for a break-out.

Citations

- ↑ Arnold 2012.

- ↑ Lehrer 2006, pp. 117, 119, 123.

- ↑ Kellerhoff 2004, p. 56.

- ↑ Mollo 1988, p. 28.

- ↑ Lehrer 2006, p. 117.

- ↑ Lehrer 2006, p. 123.

- ↑ McNab 2014, pp. 21, 28.

- ↑ Lehrer 2006, pp. 117, 119, 121–123.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, p. 97.

- 1 2 McNab 2014, p. 28.

- 1 2 McNab 2011, p. 109.

- 1 2 3 McNab 2014, p. 29.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, pp. 97, 901–902.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, p. 901.

- ↑ Lehrer 2006, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Taylor 2007, p. 184.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 278.

- 1 2 Kershaw 2008, p. 902.

- 1 2 Bullock 1999, p. 785.

- ↑ Speer 1971, p. 597.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, p. 903.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, pp. 217–233.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 251.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 255.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, pp. 267–268.

- ↑ Ziemke 1969, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, pp. 255, 256.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 275.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, p. 934.

- ↑ Ziemke 1969, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 Dollinger 1997, p. 228.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, pp. 923–925, 943.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, pp. 943–946.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, p. 946.

- 1 2 Ziemke 1969, p. 119.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 342.

- ↑ Ziemke 1969, p. 118.

- 1 2 3 4 Dollinger 1997, p. 239.

- 1 2 Beevor 2002, p. 343.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, p. 950.

- ↑ Ziemke 1969, p. 120.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 357, last paragraph.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 358.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 1999, pp. 160–182.

- ↑ Linge 2009, p. 199.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, pp. 956–957.

- ↑ Williams 2005, pp. 324, 325.

- ↑ Shirer 1960, pp. 1135–1137.

- 1 2 Joachimsthaler 1999, p. 52.

- 1 2 Beevor 2002, p. 381.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, pp. 383, 389.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 387.

- ↑ Weale 2012, p. 407.

- ↑ Hamilton 2020, pp. 349, 386.

- ↑ Hamilton 2020, p. 408.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, pp. 387, 388.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 1999, p. 287.

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 398.

- ↑ O'Donnell 2001, pp. 9–12.

- ↑ Kellerhoff 2004, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Kellerhoff 2004, pp. 98–101.

- ↑ Musmanno, Michael A. (1950). Ten Days to Die. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. pp. 233–34.

- ↑ Kellerhoff 2004, pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Mollo 1988, pp. 48, 49.

- ↑ Mollo 1988, pp. 49, 50.

- ↑ Mollo 1988, pp. 46, 48, 50–53.

- ↑ McNab 2014, p. 21.

- ↑ Kellerhoff 2004, pp. 27, 28.

- ↑ Kellerhoff 2004, p. 27.

- ↑ Der Spiegel 2006.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Dietmar (9 January 2012) [8 June 2010]. "Berliner Unterwelten e.V.: The Legend of Hitler's Bunker". Berliner-unterwelten.de. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- Beevor, Antony (2002). Berlin: The Downfall 1945. London: Viking–Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-03041-5.

- Bullock, Alan (1999) [1952]. Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. New York: Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 978-1-56852-036-0.

- Dollinger, Hans (1997). Decline and the Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. London: Chancellor. ISBN 978-0-7537-0009-9.

- Hamilton, Stephan (2008). Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault on Berlin, April 1945. Solihull: Helion & Co. ISBN 978-1-906033-12-5.

- Hamilton, A. Stephan (2020) [2008]. Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault on Berlin, April 1945. Helion & Co. ISBN 978-1912866137.

- Joachimsthaler, Anton (1999) [1995]. The Last Days of Hitler: The Legends – The Evidence – The Truth. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 978-1-86019-902-8.

- Kellerhoff, Sven (2004). The Führer Bunker. Berlin: Berlin Story Verlag. ISBN 978-3-929829-23-5.

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

- Lehrer, Steven (2006). The Reich Chancellery and Führerbunker Complex. An Illustrated History of the Seat of the Nazi Regime. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2393-4.

- Linge, Heinz (2009). With Hitler to the End. London; New York: Frontline Books–Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60239-804-7.

- McNab, Chris (2011). Hitler's Masterplan: The Essential Facts and Figures for Hitler's Third Reich. Amber Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1907446962.

- McNab, Chris (2014). Hitler's Fortresses: German Fortifications and Defences 1939–45. Oxford; New York: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-828-6.

- Mollo, Andrew (1988). Ramsey, Winston (ed.). "The Berlin Führerbunker: The Thirteenth Hole". After the Battle. London: Battle of Britain International (61).

- MI5 staff (2005). "Hitler's last days". mi5.gov.uk. MI5. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - O'Donnell, James P. (2001) [1978]. The Bunker. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80958-3.

- Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.

- Speer, Albert (1971) [1969]. Inside the Third Reich. New York: Avon. ISBN 978-0-380-00071-5.

- Staff (9 June 2006). "Debunking Hitler: Marking the Site of the Führer's Bunker". Spiegel Online. Spiegel-Verlag. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- Taylor, Blaine (2007). Hitler's Headquarters: From Beer Hall to Bunker, 1920–1945. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac. ISBN 978-1-57488-928-4.

- Weale, Adrian (2012). Army of Evil: A History of the SS. New York: Caliber Printing. ISBN 978-0-451-23791-0.

- Williams, Andrew (2005). D-Day to Berlin. Hodder. ISBN 978-0-340-83397-1.

- Ziemke, Earl F. (1969). Battle For Berlin: End Of The Third Reich. London: MacDonald. OCLC 253711605.

Further reading

- Boldt, Gerhard (1973). Hitler: The Last Ten Days. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan. ISBN 978-0-698-10531-7.

- C.I.U. General Staff, Geographical Section (1990). Ramsey, Winston G. (ed.). Berlin: Allied Intelligence Map of Key Buildings. After the Battle – Battle of Britain International. ISBN 978-1-870067-33-1.

- de Boer, Sjoerd (2021). Escaping Hitler's Bunker: The Fate of the Third Reich Leaders. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-52679-269-3.

- Fest, Joachim (2005). Inside Hitler's Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich. New York: Picador. ISBN 978-0-374-13577-5.

- Galante, Pierre; Silianoff, Eugene (1989). Voices from the Bunker. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-3991-3404-3.

- Junge, Traudl (2004). Müller, Melissa (ed.). Until the Final Hour: Hitler's Last Secretary. New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55970-728-2.

- Neubauer, Christoph (2010). Stadtführer durch Hitlers Berlin (in German and English). Frankfurt on the Oder: Flashback Medienverlag. ISBN 978-3-9813977-0-3. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- Petrova, Ada; Watson, Peter (1995). The Death of Hitler: The Full Story with New Evidence from Secret Russian Archives. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-03914-6.

- Ryan, Cornelius (1966). The Last Battle. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Tissier, Tony Le (1999). Race for the Reichstag: The 1945 Battle for Berlin. London; Portland, OR: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-4929-0.

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1992) [1947]. The Last Days of Hitler (paperback ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-81224-3.

External links

- Cosgrove, Ben. "After the Fall: Photos of Hitler's Bunker and the Ruins of Berlin". Life Magazine. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- Latson, Jennifer (16 January 2015). "The Brief Luxurious Life of Adolf Hitler, 50 Feet Below Berlin". Time Magazine. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- Shuger, Scott; Berger, Donald (21 June 2006). "Hitler Slept Here: The too-secret history of the Third Reich's most famous place". Slate Magazine.

- 3D-stereoscopic images of Chancellery

- Hitler's Bunker, National Geographic UK.