In feature-oriented software development, feature-oriented software development program cubes (FOSD program cubes) are n-dimensional arrays of functions (program transformations) that represent n-dimensional product lines. A program is a composition of features: a base program is augmented with increments in program functionality, called features, to produce a complex program. A software product line (SPL) is a family of related programs. A typical product line has F0 as a base program, and F1..Fn as features that could be added to F0. Different compositions of features yield different programs. Let + denote the feature composition operation. A program P in SPL might have the following expression:

- P = F8 + F4 + F2 + F1 + F0

That is, P extends program F0 with features F1, F2, F4, and F8 in this order.

We can recast P in terms of a projection and contraction of a 1-dimensional array. Let Fi = [F0 .. Fn] denote the array of features used by a product line. A projection of Fi eliminates unneeded features, yielding a shorter array (call it) Gi. A contraction of Gi sums each Gi in a specific order, to yield a scalar expression. The expression for P becomes:

where the index values accomplish projection and summation is array contraction. This idea generalizes to n-dimensional arrays that model multi-dimensional product lines.

Multi-dimensional product lines

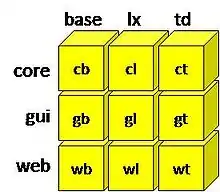

A multi-dimensional product line is described by multiple interacting sets of features.[1] [2] [3] [4] As an elementary 2D example, it is easy to create a product line of calculators, where variants offer different sets of operations. Another variation might offer different presentation front ends to calculators, one with no GUI, another with a Java GUI, a third with a web GUI. These variations interact: each GUI representation references a specific calculator operation, so each GUI feature cannot be designed independently of its calculator feature. Such a design leads to a matrix: columns represent increments in calculator functionality, and rows represent different presentation front-ends. Such a matrix M is shown to the right: columns allow one to pair basic calculator functionality (base) with optional logarithmic/exponentiation (lx) and trigonometric (td) features. Rows allow one to pair core functionality with no front-end (core), with optional GUI (gui) and web-based (web) front-ends.

An element Mij implements the interaction of column feature i and row feature j. For example, the element labeled cb is a base program that implements the core functionality of a calculator. Element gb adds code that displays the core functionality as a GUI; element wb adds code that displays the core functionality via the web. Similarly, element ct adds trigonometric code to the core calculator functionality; elements gt and wt add code to display the trigonometric functionality as a GUI and web front-ends.

A calculator is uniquely specified by two sequences of features: one sequence defines the calculator functionality, the other the front-end. For example, calculator C that offers both base and trig functionality in a web format is defined by the expression:

- Note: Each dimension is a collection of base programs and features. Not all of their compositions are meaningful. A feature model defines the legal combinations of features. Thus, each dimension would have its own feature model. It is possible that selected features along one dimension may preclude or require features along other dimensions. In any case, these feature models define the legal combinations of features in a multidimensional product line.

Cubes

In general, a cube is an n-dimensional array. The rank of a cube is its dimensionality. A scalar is a cube of rank 0, a vector is a cube of rank 1, and a matrix is rank 2. Following tensor notation: the number of indices a cube has designates its rank. A scalar S is rank 0 (it has no indices), Vk is a vector (rank 1), Mij is a matrix (rank 2), Cijk is a cube (rank 3).

Program Cubes are n-dimensional arrays of functions (program transformations) that represent n-dimensional product lines. The values along each axis of a cube denote either a base program or a feature that could elaborate a base program. The rank of a product line is the rank of its cube.

- Note: program cubes are inspired by tensors and data cubes in databases. The primary difference is that data cube elements are numerical values that are added during cube contraction; program cube elements are transformations that are composed. Both use tensor notations and terminology.

A program in an n-dimensional SPL is uniquely specified by n sequences of features S1..Sn, one per dimension. The design of a program is a scalar (expression) that is formed by (1) projecting the cube of its unneeded elements, and (2) contracting the resultant kcube to a scalar:

Program generation is evaluating the scalar expression to produce program P.

An interesting property of cube design is that the order in which dimensions are contracted does not matter—any permutation of dimensions during contraction results in a different scalar expression (i.e. a different program design), but all expressions produce the same value (program). For example, another expression (design) to produce calculator C contracts dimensions in the opposite order from its original specification:

- C = Mcb + Mwb + Mct + Mwt

Or more generally:

- Note: Underlying cube designs is a commutative diagram, such that there are an exponential number of paths from the empty program 0 to program P. Each path denotes a particular contraction of a cube, and corresponds to a unique incremental design of P. Included among these paths are cube aggregations that contract cubes using different dimensional orders.

The significance of program cubes is that it provides a structured way in which to express and build multi-dimensional models of SPLs. Further, it provides scalable specifications. If each dimension has k values, an n-cube specification of a program requires O(kn) terms, as opposed to O(kn) cube elements that would otherwise have to be identified and then composed. In general, cubes provide a compact way to specify complex programs.

Applications

The expression problem (a.k.a. the 'extensibility problem) is a fundamental problem in programming languages aimed at type systems that can add new classes and methods to a program in a type-safe manner.[5][6][7][8] It is also a fundamental problem in multi-dimensional SPL design. The expression problem is an example of an SPL of rank 2. The following applications either explain/illustrate the expression problem or show how it scales to product lines of large programs. EP is really a SPL of ~30 line programs; the applications below show how these ideas scale to programs of >30K lines (a 103 increase in size).

- Expression Problem

- Illustration of Small Expression Problem

- Extensible IDEs

- Multi-Dimensional Separation of Concerns

- Calculator Product Line

Also, FOSD metamodels can be viewed as special cases of program cubes.

References

- ↑ "Generating Product-Lines of Product-Families" (PDF).

- ↑ "Refinements and Multi-Dimensional Separation of Concerns" (PDF).

- ↑ "Scaling Step-Wise Refinement" (PDF).

- ↑ "Evaluating Support for Features in Advanced Modularization Technologies" (PDF).

- ↑ User-defined types and procedural data structures as complementary approaches to data abstraction. MIT Press. 12 August 1994. pp. 13–23. ISBN 9780262071550.

- ↑ "Object-Oriented Programming versues Abstract Data Types" (PDF).

- ↑ "The Expression Problem".

- ↑ "Synthesizing Object-Oriented and Functional Design to Promote Re-Use".