| This article is part of a series on |

| Driving cycles |

|---|

| Europe |

|

NEDC: ECE R15 (1970) / EUDC (1990) (UN ECE regulations 83 and 101) |

| United States |

| EPA Federal Test: FTP 72/75 (1978) / SFTP US06/SC03 (2008) |

| Japan |

| 10 mode (1973) / 10-15 Mode (1991) / JC08 (2008) |

| Global Technical Regulations |

| WLTP (2015) (Addenda 15) |

The EPA Federal Test Procedure, commonly known as FTP-75 for the city driving cycle, are a series of tests defined by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to measure tailpipe emissions and fuel economy of passenger cars (excluding light trucks and heavy-duty vehicles).

The testing was mandated by the Energy Tax Act of 1978[1] in order to determine the rate of the guzzler tax that applies for the sales of new cars.

The current procedure has been updated in 2008 and includes four tests: city driving (the FTP-75 proper), highway driving (HWFET), aggressive driving (SFTP US06), and optional air conditioning test (SFTP SC03).

City driving

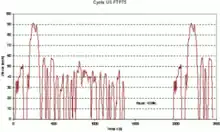

UDDS

The Urban Dynamometer Driving Schedule is a mandated dynamometer test on tailpipe emissions of a car that represents city driving conditions. It is defined in 40 CFR 86.I.[2][3]

It is also known as FTP-72 or LA-4, and it is also used in Sweden as the A10 or CVS (Constant Volume Sampler) cycle and in Australia as the ADR 27 (Australian Design Rules) cycle.[4]

The cycle simulates an urban route of 7.5 mi (12.07 km) with frequent stops. The maximum speed is 56.7 mph (91.2 km/h) and the average speed is 19.6 mph (31.5 km/h).

The cycle has two phases: a "cold start" phase of 505 seconds over a projected distance of 3.59 mi at 25.6 mph average speed, and a "transient phase" of 864 seconds, for a total duration of 1369 seconds.

FTP-75

The "city" driving program of the EPA Federal Test Procedure is identical to the UDDS plus the first 505 seconds of an additional UDDS cycle.[5][6]

Then the characteristics of the cycle are:

- Distance travelled: 11.04 miles (17.77 km)

- Duration: 1874 seconds

- Average speed: 21.2 mph (34.1 km/h)

The procedure is updated by adding the "hot start" cycle that repeats the "cold start" cycle of the beginning of the UDDS cycle. The average speed is thus different but the maximum speed remains the same as in the UDDS. The weighting factors are 0.43 for the cold start and transient phases together and 0.57 for the hot start phase.

Though it was originally created as a reference point for fossil fuelled vehicles, the UDDS and thus the FTP-75, are also used to estimate the range in distance travelled by an electric vehicle in a single charge.[7]

Deceptions

It is alleged that, similarly than in the NEDC, some automakers overinflate tyres, adjusting or disconnecting brakes to reduce friction, and taping cracks between body panels and windows to reduce air resistance, some go as far as removing wing mirrors, to inflate measured fuel economy and lower measured carbon emission.[8]

In addition, it has been brought to attention that the relative height of the simulated wind fan with respect to the vehicle could alter the performance of aftertreatment systems due to changes in temperature and, consequently, modify the pollutant emissions values.[9]

Highway driving

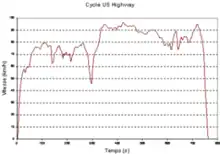

The "highway" program or Highway Fuel Economy Driving Schedule (HWFET) is defined in 40 CFR 600.I.[10]

It uses a warmed-up engine and makes no stops, averaging 48 mph (77 km/h) with a top speed of 60 mph (97 km/h) over a 10-mile (16 km) distance.

The following are some characteristic parameters of the cycle:

- Duration: 765 seconds

- Total distance: 10.26 miles (16.45 km)

- Average Speed: 48.3 mph (77.7 km/h)

- Maximum acceleration: 3.2 mph/sec

Before the 5-cycle fuel economy estimates were introduced in 2006 the measurements were adjusted downward by 10% (city) and 22% (highway) to more accurately reflect real-world results.[11]

Supplemental tests

In 2007, the EPA added three new Supplemental Federal Test Procedure (SFTP) tests[12] that combine the current city and highway cycles to reflect real world fuel economy more accurately,. Estimates are available for vehicles back to the 1985 model year.[5][13]

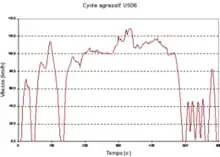

US06

The US06 Supplemental Federal Test Procedure (SFTP) was developed to address the shortcomings with the FTP-75 test cycle in the representation of aggressive, high speed and/or high acceleration driving behavior, rapid speed fluctuations, and driving behavior following startup.

SFTP US06 is a high speed/quick acceleration loop that lasts 10 minutes, covers 8 miles (13 km), averages 48 mph (77 km/h) and reaches a top speed of 80 mph (130 km/h). Four stops are included, and brisk acceleration maximizes at a rate of 8.46 mph (13.62 km/h) per second. The engine begins warm and air conditioning is not used. Ambient temperature varies between 68 °F (20 °C) to 86 °F (30 °C).

The cycle represents an 8.01 mile (12.8 km) route with an average speed of 48.4 miles/h (77.9 km/h), maximum speed 80.3 miles/h (129.2 km/h), and a duration of 596 seconds.

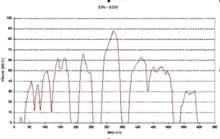

SC03

The SC03 Supplemental Federal Test Procedure (SFTP) has been introduced to represent the engine load and emissions associated with the use of air conditioning units in vehicles certified over the FTP-75 test cycle.

SFTO SC03 is the air conditioning test, which raises ambient temperatures to 95 °F (35 °C), and puts the vehicle's climate control system to use. Lasting 9.9 minutes, the 3.6-mile (5.8 km) loop averages 22 mph (35 km/h) and maximizes at a rate of 54.8 mph (88.2 km/h). Five stops are included, idling occurs 19 percent of the time and acceleration of 5.1 mph/sec is achieved. Engine temperatures begin warm.

The cycle represents a 3.6 mile (5.8 km) route with an average speed of 21.6 miles/h (34.8 km/h), maximum speed 54.8 miles/h (88.2 km/h), and a duration of 596 seconds.

Cold cycle

A cold temperature cycle uses the same parameters as the current city loop, except that ambient temperature is set to 20 °F (−7 °C).

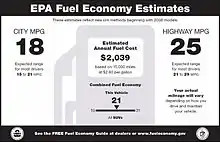

EPA fuel economy sticker

EPA tests for fuel economy do not include electrical load tests beyond climate control, which may account for some of the discrepancy between EPA and real world fuel-efficiency. A 200 W electrical load can produce a 0.94 mpg (0.4 km/L) reduction in efficiency on the FTP 75 cycle test.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Frequently Asked Questions. Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved on 21 September 2011.

- ↑ United States Code of Federal Regulations, Title 40: Protection of Environment, Part 86: Control of emissions from new and in-use highway vehicles and engines, 40 CFR 86.I

- ↑ United States Environmental Protection Agency#Fuel economy

- ↑ DieselNet Emission Test Cycles - FTP-72 (UDDS)

- 1 2 "Dynamometer Drive Schedules". US EPA. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ DieselNet Emission Test Cycles - FTP-75

- ↑ Chuck Squatriglia. "Honda finds EVs a perfect fit". Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ Ciferri, Luca (8 Nov 2017). "Automakers could face big fines under new EU testing regime". The Automotive News. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ Fernández-Yáñez, P.; Armas, O.; Martínez-Martínez, S. (2016). "Impact of relative position vehicle-wind blower in a roller test bench under climatic chamber". Applied Thermal Engineering. 106: 266–274. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.06.021.

- ↑ United States Code of Federal Regulations, Title 40: Protection of Environment, Part 600: Fuel economy and greenhouse gas exhaust emissions of motor vehicles, 40 CFR 600.I

- ↑ Auto Editors of Consumer Guide (7 September 2005). "How the EPA fuel-economy testing works". Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ Earthcars: EPA fuel economy ratings – what's coming in 2008. Web.archive.org (8 October 2007). Retrieved on 21 September 2011.

- ↑ Find a Car 1985 to 2009. Fueleconomy.gov. Retrieved on 21 September 2011.

- ↑ John G. Kassakian; Hans Christoph Wolf; John M. Miller; Charles J. Hurton (August 1996). "Automotive Electrical Systems Circa 2005". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 24 April 2014.