Filippo Colarossi (21 April 1841 in Picinisco[1] – August 1906) was an Italian artist's model and sculptor who founded the Académie Colarossi in Paris between 1879 and 1880.

He is claimed to have died on 25 August 1906 in Paris.[2] however, Duval[3] states that Colarossi died poor and alone in August 1906 in a little town near Naples. Émile-Bayard[4] reports that Colarossi and his wife (unidentified/unconfirmed second wife; the first had died in 1896), having profited from the sale of a building plot in 1916, retired to Picinisco, his natal village, where they presumably stayed until their deaths. Fuss Amoré and des Ombiaux[5] also maintain that Colarossi returned to Italy. Writing in 1924, they maintained that Colarossi had recently returned to Picinisco, having sold some works by the artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). No female companion is mentioned in this latter source.

Biography

Leaving Italy

Born to poor parents, farm labourer (contadino) Fiori Colarossi (1779–1853)[6][7] and his wife Anna (née Ferri; 1811–?),[6] Colarossi grew up in Picinisco, a small hilltop village south east of Rome, in the Province of Frosinone of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. During the Unification of Italy, the Kingdom fell to the troops led by nationalist and anti-papal general Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882), whereupon it was incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy and asset stripped. As a Catholic and loyal royal marine, this was an unwelcome outcome to Colarossi's elder brother Angelo (1836–1916);[6][8] thus, in late 1860 or in 1861, they made their way, mostly by steam boat (Naples–Marseilles, then Avignon–Lyon), to Paris, France, to escape widespread poverty and obligatory military conscription.[9] It seems another brother, Antonio (1837–?),[6] was waiting there to welcome and help them.[10][11]

Paris and modelling

The Colarossi brothers left a life in rural Italy to start afresh in a foreign, capital city. Challenges such as the language, accommodation and paid work would have to be addressed. By chance, or perhaps by design, they had also arrived in Paris at an exciting and tumultuous time in the city's history.

In the 1860s, the city was in rapid growth in terms of population, geographical boundaries, industry, commerce and cultural activity. Starting in 1853, Napoleon III (1808–1873) and his prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann (1809–1891), had initiated an extensive series of public works projects to clean up, rebuild and modernise the capital. Old blocks of buildings were demolished. High-rise apartment houses with classical facades, wide boulevards, new sewers and more were built.[12]

Like Antonio before them,[13] both brothers soon found employment as models for artists. This was hard work as poses had to be inspiring and held for long periods of time. Nudity also conflicted with societal norms of modesty and propriety. Nonetheless, Colarossi chose to remain a model in Paris, which was fast becoming the Mecca of the Fine Arts, while Angelo left for London, England, in 1864, where he continued his newfound occupation, started a family and became an Urban District Councillor.[14] His son, Angelo Colarossi Jr., was also a model in London and posed for the sculptor Alfred Gilbert[15] amongst others.

Filippo Colarossi became a very ambitious and successful model, not least at the École Impériale des Beaux-Arts (Imperial School of Fine Arts) on the Left Bank, where he drew an annual, retaining fee of 500 francs.[16] Here, he soon acquired the titles of questeur des modèles[17] and later chef des modèles.[18] He was also a favourite model of the classicist painter Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier (1815–1891), who he met when staying at Saint-Germain-en-Laye to escape the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871).[19]

In what has been described as a fraught and arduous life, Colarossi also found time to marry and start a family of his own. On 21 July 1866, he married Ascenza Margiotta (1847–1896),[13] herself a model and native of Picinisco. In April of the same year, their first child, Ernest Flore (1866–1960) was born. They later had two girls, Maria (1868–1913) and Malia (1871–1897),[20] who both married artists.

Colarossi Academy

Colarossi wanted to establish his own school where he could provide an art education for the many students, male and female, that were flocking to Paris.

Henri Duval[19] writes that Colarossi had through 'economy and right living' saved the funds necessary to set up a school. He may also have had financial help as The Artist – An Illustrated Monthly Record of Arts, Crafts and Industries asserts that the wealthy Meissonier helped him to get started in an art school,[21] perhaps by giving him an advance.[22]

So, Colarossi purchased the then renowned Académie Suisse. This academy was established by the model[23][24] and painter of miniatures[25] Martin François Suisse (1781–1859) at 4, Quai des Orfèvres on the Île de la Cité, Paris in 1817.

In 1858, Suisse had retired and left his academy to a nephew, while remaining an honorary professor.[26] However, it was the artist Étienne Prosper Crébassol (1806–1883)[27] that soon took on the ownership, certainly the running, of the academy, renaming it Académie Suisse-Crébassol. Suisse died in 1859 at his home, aged 78.[28]

Passe writes[29] that in 1876 the Ateliers de Dessin et de Peinture were more-or-less limited to Académie Julian in the Passage des Panoramas (see Crombie) and Crébassol's insufficient, little course in Rue Gît-le-Cœur. He makes no mention of the Académie Colarossi (see below), the renowned art school, so it is doubtful it had been established. Indeed, advertisements for the school did not appear in newspapers until 1881[30] and 1882.[31] Furthermore, an article in Le Petit Journal, 1882, refers to "la nouvelle académie libre"[32] ("the new free academy"). Assertions of an earlier purchase date sometime around 1870, are made further implausible by the disruptions of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune (1871).

It would seem that Crébassol had moved the school to No. 12, Rue Gît-le-Cœur, 6th arrondissement, over the river from the Quai des Orfèvres.[33] Passe further states that two years later in 1879 the aged Crébassol sold his studio to Colarossi for the sum of 500 francs. Crébassol was by this time 73 years old and was presumably no longer able and/or willing to maintain his academy any longer. He died at home in 1883.[34]

Colarossi first renamed his acquisition Académie de la Rose ("Academy of the Rose"),[35] later renaming it Académie Colarossi. In 1881,[36] he transferred its premises to 10 Rue de la Grande Chaumière in Montparnasse (6th arrondissement).[35] where he had added six studios to his newly acquired rear courtyard premises behind a certain Miss Bonnefoy's grocery store. A Miss Ross who attended the academy in 1889, describes the entrance to the building:

"... the Colarossi. The school in which I chose to study, is situated in the Latin Quarter. Entering from the street one walks through a narrow arched passage on which open the kitchens of the adjoining houses. Then into an open square court fitted up with statues and plants and bounded by houses whose facades are ornamented with weather-stained busts and casts. One of the four-storied buildings making the side of the court is the school. ..."[37]

Colarossi was also to establish annexes, for example, at 96 Rue Blanche (9th arrondissement),[38] 13 Rue Washington (8th arrondissement),[39] and, most prominently, at 43 Avenue Victor Hugo (16th arrondissement).[40]

Colarossi wanted his academy to be a progressive school where one could get training that was not available at the more conservative École. Women and men could share classes, and women were also allowed to draw and paint nude models, both male and female. Colarossi was from the start a firm believer in mixed classes as it was an advantage to both men and women to be able to watch, compare and discuss each other's work.[41]

There was no entrance exam, but there were fees to be paid. Here, equality between the sexes was less apparent. Most schools demanded higher fees of their female students, than their male counterparts. For example, to study at the Colarossi Academy, Rue de la Grande Chaumière, the following fees applied in 1887:[42]

- for men, one month, day 16 francs, evening 15 francs

- for women, one month, day 20 francs, evening 20 francs

The usual explanation for the difference was that the attendance of women could not be relied upon. Women often remained for a month or two, but men tended to stay for years, many having the intention of seeking entry to the École des Beaux-Arts. Most women were not studying professionally, so their luxury was set at a higher price.

It must be remembered that only in 1897, after a long and heated campaign by activists, were women finally allowed to sit the entrance exam to the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris and perhaps be one of the few to study there for free, albeit with some restrictions. In 1900, female students were admitted on a more-or-less equal footing with male students, though they were not allowed to enter the competition for the prestigious Prix de Rome until 1903.

Notable students of the academy included Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Claude-Émile Schuffenecker (1851–1934), Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946), Camille Claudel (1864–1943), Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939), Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876–1907) and others.

Colarossi's considerable experience and status as a leading model allowed him to recruit the best of models, many from his native Abruzzo region of Italy. Penelope Little states that Colarossi actively enticed his impoverished countrymen to Paris where they could provide a constant and plentiful supply of affordable models.[43] In 1880, a list of models in Paris recorded that of 671 models, 230 were Italian, the rest being of various nationalities.[44]

Italian models were not just admired for their looks, but also their tractability, ability to hold the pose for long periods and dedication. Their willingness to accept lower fees was also exploited. Colarossi's compatriots became very popular models for thirty or so years before their fortunes slowly began to wane due to the move from classicism to realism in art.[45]

Every Monday for many years there was a picturesque queue or throng of such models outside No. 10 known as Le Marché aux Modèles that extended from the academy's courtyard, through the passageway and well out into the street.[46] Men, women and children sporting a variety of attire from mundane city rags to traditional costumes waited and hoped to find employment for the week knowing that they could receive more pay than in other schools.

In 1891, a newspaper correspondent, reported that models would sit, with changes and breaks, from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m., seven days a week. The only official holiday was on 14 July, when France celebrates its National Day.[47]

Colarossi also employed some of the best artists to teach at his academy. In the 1880s and 90s for example, they included painters Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848–1884), Gustave-Claude-Etienne Courtois (1852–1923), Raphaël Collin (1850–1916), Louis-Auguste Girardot (1856–1933), René Schützenberger (1860–1916), Jean-André Rixens (1846–1925) and Édouard Debat-Ponsan (1847–1913). His sculptors included Alexandre Falguière (1831–1900), Jean Antoine Injalbert (1845–1933) and Alfred Boucher (1850–1934). These artists were academically trained, but did not impose any academic orthodoxy. They would visit twice a week to give their criticism on the work of each student.[48] All students were taught by a number of teachers, and allowed to nurture any personal character or originality they might have. Colarossi and his teachers also socialised with students outside of the academy, at bars, restaurants, parties, exhibitions etc. He would often invite students to his country place at Fontenay-aux-Roses to eat and discuss Art.[49]

Colarossi did everything he could to ensure his own personal happiness and success. He believed that his academy was blessed from on high and was destined for glory. Since its first incarnation as Académie Suisse, many of its students, like Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) and the Impressionists, had become great artists. These, he believed, kept a protective eye on the academy from heaven. On Earth, he was proud of the fact that he had the pick of the best Italian models and talented teachers who took great pride in doing their utmost for the school. Thus, the living would also assure his academy's good fortune.[50]

Writing in 1889, French's view is more down-to-earth:

"The heads of the private schools, …, are not distinguished artists at all, but rather business men, managers of tact and address. Colarossi is an Italian and was formerly a model in the art schools. He is a cordial, business-like man, and does some modelling in clay. His evening classes are much frequented."[51]

Writing in 1896, when she was a student at the academy, Alice Muskett gave another realistic, more detailed and nuanced, description of the man and the personal attributes that contributed to his success:

" 'Il Padrone', M. Colarossi, comes in to see how many nouvelles there are, and also that everything goes well. I am bound to confess that M. Colarossi is not awe-inspiring in appearance; he is short and ordinary looking; dresses carelessly also. But then he is the most obliging of maestro's, always willing to accommodate his students in the matter of classes, fees, and models. Will allow you to change classes or take a week's holiday, with the best of grace, and accepts your fees quite apologetically. ... As far as one can judge, Colarossi rules his little world wisely and fairly, and he seems to possess the royal gift of remembering everyone's face and recognising them when he meets them."[52]

In reality, though Colarossi's academy became a great success, it was not all plain sailing. Writing in 1890, Harrison[53] asserts that the academy was reduced to half its former size by the draining influence of its great rival, the Académie Julian, whose paid professors dominated the Salon and favoured Julian's 600–800 students.

As an artist in his own right

As hinted above, Colarossi also became an artist; no doubt availing himself of the excellent teachers at his own academy. Under the name of Philippe, or Filippo, Colarossi, he exhibited sculptures at:

- The Salon of French Artists in Paris from 1882–89;[54]

- the Société des Amis des Arts du Département de Seine-et-Oise, 35th Exposition Versaillaise of 1888, Versailles[55]

- the Universal Exposition of 1889, Paris;[56]

- the Royal Academy Exhibitions of 1884 and 1888, London;[57]

- the Grovesnor Gallery, London in 1884.[58] and 1885[59]

So, not only could he advise on posing the academy's models, he could now help to nurture his students' artistic talents.[60] In 1889, a Miss B.-M. Ross who studied in Paris and exhibited at the Salon of 1889 said of Colarossi:

"Our critics were among the best artists of France. Monsieur Callarossi [sic], at the head of the school, is a sculptor of some little note in Paris. His works appear year upon year at the Salon. He rose from a model and has made himself universally beloved by the students by his sympathy with their work and his way of dealing. …"[61]

In 1884, Colarossi became a member of the Association des Artistes,[62] a non-profit foundation launched by Baron Isidore Taylor (1789–1879) in 1844 for the protection and assistance of artists. The association was one of the most prestigious bastions of the Beaux-Arts and membership was a way of obtaining affirmation of one's artistic credentials and finding new contacts to further one's ambitions.

As a cyclist

Colarossi's life was demanding, however he did find time for recreation. In the early 1890s, he developed a passion for cycling which was experiencing a boom resulting from several significant technical developments in bicycle design.

In 1893, he and some of his students organised a 40 km, summer, bicycle race for painters, sculptors and architects under the patronage of the newspapers Le Vélo and La Bicyclette. It came to be known as La Course des Trois Arts ("The Three Arts' Race"). Colarossi was the organising committee's treasurer, while artists Carolus Duran (1837–1917), Courtois and Alfred Philippe Roll (1846–1919) were honorary presidents.[63][64]

The races were primarily for amateurs, but some professionals like Henri Farman (1874–1958), Vasseur and Lambert also participated.[65] Prizes such as medals, journal subscriptions and tyres could be won. In 1895, Colarossi offered a term at his academy as a prize.[66]

Though in his early fifties, in 1893[67] and 1894,[68] Colarossi paid the 5 francs entry and took part in the race. His finishing times are not recorded.

He also took part, along with others, in a twelve hour, endurance match against the noted journalist and cycle racer Édouard de Perrodil (1860–1931).[69]

For Colarossi, the bicycle may have had its quotidian uses in getting around Paris, as in 1895, he was spotted riding a bicycle through the Bois de Boulogne, not far from his academy's premises on Avenue Victor Hugo.[70]

Not one to miss a celebration, Colarossi also attended the festive, post-race banquets that were held for participants and organisers after each race. His son, Ernest Flore, engraver and pupil of Paul-Edme Le Rat,[71] was present in 1896.[72]

Colarossi and his academy continued to play an active, organisational role until the last Course des Trois Arts in 1898.[73]

Later years and death

With the years, Colarossi became something of a bohémien or bon vivant who cultivated the appearance of an aristocrat.[74] The robust, hard-working model and renowned, art-school proprietor, began to stroll the boulevards, to frequent chic cafés and develop a penchant for English clothing. He indulged in those pleasures that Paris could offer those with money to spare and an easy conscience. Despite the fact that his academy was as popular and remunerative as ever, the high life of women and drink began to take its toll. But, it was Colarossi's betting on horses, with disastrous results, that forced him to close the academy's doors in the winter of 1901–1902.[75] Duval reports that, "At the time of his death, the academy was and still is being run for the benefit of his creditors, according to the French law."[3]

On 19 March 1910, the financially embarrassed academy,[76] was advertised[77] as being for sale on 18 April for the sum of 10,000 francs. The sale of the academy put its fate in the balance. The possibility of its imminent demolition so worried one of its American students, that (s)he wrote a reader's letter to the New York Herald asking for a rich compatriot to come forward who would be prepared to build a new, flagship, art school on the academy's hallowed ground. Thus, future students could continue to access to the best education possible.[78]

Seemingly, Colarossi's son Ernest found the necessary capital, as he is recorded as succeeding his father in Le Courrier,[79] a daily journal of judicial and legal notices, also on 18 April.

The academy certainly avoided closure as there were classes in November 1911,[80] and Ernest is recorded as being very much in control of the academy in 1912.[81][82]

In a meeting at the academy in 1913, the Société Internationale des Anciens Élèves des Académies Suisse-Crébassol-Colarossi ("International Society of the Former Pupils of the Suisse, Crébassol and Colarossi Academies") was formed. Its president was the renowned sculptor Jean Antoine Injalbert and its aim was to hold exhibitions by former students, both in France and abroad. The society would celebrate the contributions of the three schools to the world of art and promote the works of their students. However, the initiative seems to have failed, perhaps due to the advent of the First World War.[83]

Various online sources[84] state that Madame Colarossi (presumably his second wife) burned the academy's priceless archives in retaliation for her husband's philandering and that the academy subsequently closed in the 1920s or 30s. The first claim regarding the archive is entirely anecdotal reiteration and is not supported by any references. The dating of the academy's closure is simply incorrect. It was still open and very active in the 1940s[85] and 1950s.[86]

Returning to the subject of Colarossi's last years, the death registration[87] of Maria Hiolle, née Colarossi, who died on 31 July 1913, states that her parents, Filippo Colarossi and Ascensa Margietta [sic] were both dead. So, Colarossi could not have gone back to Italy in or after 1913. The information above regarding his last years and his claimed return to Italy may be correct, but the date of that return needs some scrutiny. The date and place of Colarossi's death are still a matter of investigation.

Notes

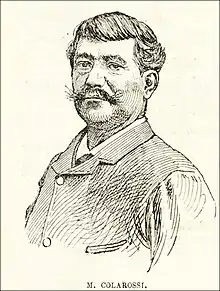

- The photograph on which this print is based can be found in an article published in Pall Mall Magazine: 'Unknown Paris, Part III - Artist: Their lives, pleasures and haunts' by M. Griffith and Jean d'Oriol, Pall Mall Magazine, Vol. VII., September to December 1859, No. 31., November 1895, London, pp. 379–390. The magazine can be accessed on the hathitrust.org website.

References

- ↑ As mentioned in his marriage documents from 21 July 1866 in Paris, 6th arrondissement (available at http://archives.paris.fr/r/284/etat-civil-a-partir-de-1860/).

- ↑ Le Paul, Charles-Guy, Gauguin and the impressionists at Pont-Aven, New York, Abbeville Press, 1987, p. 130.

- 1 2 Duval, Henri (28 February 1909). "Romance deserts the Lives of Paris Artists' Models". The Illustrated Buffalo Express. Buffalo, New York State, USA. p. 12.

- ↑ Émile-Bayard, Jean (1927). Montparnasse, hier et aujourd'hui: ses artistes et écrivains, étrangers et français, les plus célèbres (in French). Paris, France: Jouve et Cie. p. 395.

- ↑ Fuss-Amoré, Gustave et des Ombiaux, Maurice, Montparnasse (II, fin), Mercure de France, 15 November 1924, p. 110

- 1 2 3 4 1841 Parish census of Picinisco, entry 338 - Colarossi di Settefrati - copy obtained via genealogist Ann Tatangelo, Sora, Italy, 2013, angelresearch.net

- ↑ Antenati Gli Archivi per la Ricerca Anagrafica http://www.antenati.san.beniculturali.it Home› Sfoglia i registri› Archivio di Stato di Caserta› Stato civile napoleonico e della restaurazione› Picinisco(provincia di Frosinone)› Morti› 1853› 184.16411› Immagine 3 Home› Sfoglia i registri› Archivio di Stato di Caserta› Stato civile napoleonico e della restaurazione› Picinisco(provincia di Frosinone)› Morti› 1853 › 184.16411› Immagine 45 > Entry no. 75

- ↑ "Death Register". 13 May 2021.

- ↑ Whittam, John (1977). Politics of the Italian Army, 1861-1918. London: Croom Helm Ltd. ISBN 9780208015976.

- ↑ Fraser, A. Hugh (March 1896). "Angelo Colarossi". The Beam. National Art Training School. Two: 73.

- ↑ Registres d'actes d'état civil (1860-1902), Acte de Mariage, 6e arr, 26-07-1866, No. 515, Colarossi et Margiotta, Archives numérisées de Paris, Mairie de Paris, paris.fr - Antonio is a witness

- ↑ Ahlund, Mikael; Bengtsson, Anders; Ernstell, Micael; Hejdelind, Veronica; Kåberg, Helena; Olin, Martin; Olsson, Carl-Johan; Hedström, Per (2012). Modern Life - France in the 19th Century. Stockholm, Sweden: Nationalmuseum, Sweden. p. 33. ISBN 978-91-7100-837-4.

- 1 2 Archives de Paris, Marriages, 6ème Arr., V4E 711, 21/07/1866, No. 515

- ↑ Kelly's Directory of Essex (11th ed.). London: Kelly’s Directories Ltd. 1914. p. 154.

- ↑ Scott Thomas Buckle, "A Waterhouse Sketch Discovered", In: The Art and Life of John William Waterhouse (1849-1917) — Archive Today.

- ↑ B., H. (13 April 1887). "The Ateliers of Paris". Boston Post. Boston, New England, USA. p. 2.

- ↑ Fuss-Amoré, Gustave et des Ombiaux, Maurice, Montparnasse (II, fin), Mercure de France, 15 November 1924, p. 107

- ↑ Courthion, Pierre (19 November 1932). "De Julian à la Grande Chaumière". Les Nouvelles littéraires, artistiques et scientifiques (in French). Paris: 7.

- 1 2 Duval, Henri (28 February 1909). "Romance Deserts the Lives of Paris Artists' Models". New York Press. New York, USA. p. 4.

- ↑ Ernest Flore Colarossi, Actes d'état civil, Naissances, 6e arr Paris, No. 1103, 27-04-1866, Marie de Paris, paris.fr. Has an annotation recording Ernest's death 11 April 1960 in the commune of Versailles. Maria Colarossi, Actes d'état civil, Naissances, 6e arr Paris, No. 1363, 02-06-1868, Marie de Paris, paris.fr Maria Colarossi femme Hiolle, Actes de l'État Civil, Actes de décès de la commune de Sceaux pour l'an 1913, No 44, Document E_NUM_SCE_D1913, archives.hauts-de-seine.net Malia Colarossi, Registres d'état-civil, Naissances, Poissy, No. 31, 21-04-1871, Archives des Yvelines, archives.yvelines.fr Malia Ravelet née Colarossi, Registre d'actes, Décès, 1893-1897, Arcueil, Archives de Val-de-Marne, archives.valdemarne.fr

- ↑ T., H.; De V., M.; B. S., C. (August 1899). "Art Centres". The Artist: An Illustrated Monthly Record of Arts, Crafts and Industries (American Edition). 25 (235): 157–160. doi:10.2307/25581428. JSTOR 25581428.

- ↑ Courthion, Pierre (19 November 1932). "De Julian à la Grande Chaumière". Les Nouvelles littéraires, artistiques et scientifiques (in French). Paris, France: 7.

- ↑ Noël, Benoit (2006). 'Parisiana - la capitale des peintres au XIXème siècle (in French). Les Presses Franciliennes. p. 134.

- ↑ Benhamou, Reed (1997). "Diderot et l'enseignement de Jacques-Louis David". Recherches sur Diderot et sur l'Encyclopédie (in French). 22: 82. doi:10.3406/rde.1997.1377.

- ↑ Dulac, Henri (1835). Almanach des 25000 adresses des principaux habitants de Paris pour l'année 1835 (in French). Paris: C.L.F. Panckoucke. p. 538.

- ↑ D'Ivol, Paul (25 December 1859). "Feu Suisse". Le Figaro (in French). Paris, France. p. 6.

- ↑ From Filae.com, 8 juillet 2021. Archives Départementales de Paris Décès Le 04 juin 1883 Paris 9EME (Paris, Paris) Individu concerné: Etienne Prosper CREBASSOL, No. 878 NB.: Sépulture Le 05 juin 1883 Cimetière parisien de Saint-Ouen (93) ((Saint-Ouen) Saint-Ouen-sur-Seine, Seine-Saint-Denis) Inhumation

- ↑ Princip, Val C. (1904). Spielmann, M.H. (ed.). "A Student's Life in Paris 1859". The Magazine of Art. London, England: La Belle Savvage [sic]: 340 – via Archive.org.

- ↑ Passe, Jean (15 February 1891). Dupray, Paul (ed.). "Ateliers Libres". Journal des Artistes - Revue hebdomadaire des Beaux-Arts (in French). Paris, France: 46.

- ↑ Anon. (17 April 1881). "Advertisement for Académie Colarossi". L'Estampe - Annuaire de la Gravure (in French). Paris, France. p. 4.

- ↑ Anon. (17 November 1882). "Académie Colarossi". Moniteur des Arts (in French). p. 364.

- ↑ Anon. (5 March 1882). "Nouvelles Artistiques". Le Petit Journal (in French). p. 2.

- ↑ Passe, Jean (3 February 1889). Dupray, Paul (ed.). "Causerie". Journal des Artistes - Revue hebdomadaire des Beaux-Arts (in French). Paris, France: 37–38.

- ↑ From Filae.com, 8 juillet 2021. Archives Départementales de Paris. Décès: 04 juin 1883, Paris 9EME. Individu concerné: Etienne Prosper CREBASSOL, No. 878 NB.: Sépulture: 05 juin 1883, Cimetière parisien de Saint-Ouen (93) ((Saint-Ouen) Saint-Ouen-sur-Seine, Seine-Saint-Denis) Inhumation

- 1 2 Noël, Benoît et Hournon, Jean, Parisiana: la capitale des peintres au XIXème siècle, Les Presse Franciliennes, Paris, 2006, p. 134

- ↑ Crombie, John (2003). CHEZ CHARLOTTE - and Fin-de-Siècle Montparnasse. Paris France: Kickshaws. p. 11.

- ↑ Anon. (6 October 1889). "Touching up the Artists". The Sunday Morning Express. Buffalo, New York, USA. p. 5. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ↑ Anon. (12 November 1892). "Gazette du Jour". La Justice (in French). Paris, France. p. 3.

- ↑ Anon. (21 December 1883). Esmont, Henry (ed.). "Ateliers de Peintures". Journal des Artistes (in French). Paris, France. p. 4.

Nouvel Atelier de Dames

- ↑ Ayral-Clause, Odile. Camille Claudel: A Life. Plunkett Lake Press. Pub. 2002, p. 25.

- ↑ Anon. (26 March 1900). "Studios Abroad". London, England. p. 4.

- ↑ Anon. (1887). The Art Student in Paris. Boston, Mass., USA: Boston Art Students' Association. pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Little, Penelope (2003). A Studio in Montparnasse - Bessie Davidson, An Australian Artist in Paris. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: Craftsman House. p. 32.

- ↑ Anon. (16 July 1880). "Artists' Models in Paris". The New York Times. p. 2.

- ↑ Valensol (12 August 1901). "Les Modèles". Le Petit Parisien (in French). p. 2.

- ↑ Blanchard, Florence (10 November 1895). "The Ateliers of Paris". The San Francisco Call. p. 28.

- ↑ Anon. (19 September 1891). "Australian art students in Paris". The Age. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. p. 4. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ↑ Anon. (19 September 1891). "Australian Art Students in Paris". The Age. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. p. 4.

- ↑ Anon. (2 September 1899). "Round the Studios - Colorossi's [sic]". M.A.P. (Mostly About People). London. p. 203. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ↑ Bullett, Emma (21 April 1889). "Colarossi's Art School". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York, USA. p. 8.

- ↑ French, W.M.R. (21 April 1889). "Art Students Abroad". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 33.

- ↑ Muskett, Alice (24 February 1896). "A Day at the Atelier Colarossi". The Daily Telegraph. Sydney, NSW, Australia. p. 6. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ↑ Harrison, Birge (December 1890). "The New Departure in Parisian Art". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. LXVI. p. 758. hdl:2027/coo.31924079618850 – via Hathi Trust.

- ↑ 1882-1889, Catalogue Illustré du Salon, publié sous la direction de F. -G. Dumas, Pub. Librairie d'Art Ludovic Baschet, editeur, Paris, 1882-1889. Catalogues found on Gallica website: gallica.bnf.fr Examples: 1882, Sculpture: no. 4231 Colarossi (P.). Jeune Florentin; buste, plâtre, no. 4232 Première pensée; buste, plâtre. 1889, Sculpture: no. 4196 Colarossi (F.). La Première Pensée; - buste, plâtre.

- ↑ Anon. (1888). Description des Ouvrages de Peinture, Sculpture, Architecture, Gravure, Miniatures, Dessins et Pastels exposés dans les Salles du Musée de Versailles, 1888 (in French). Versailles, France: Société des Amis des Arts du Département de Seine-et-Oise. p. 81.

- ↑ Exposition Universelle de 1889, Publié sous la direction de F. -G. Dumas. Pub. Baschet, Paris, page 99. Sculptures, 318 - COLAROSSI (F.). Vengeance; - buste, bronze. Found on Gallica website: gallica.bnf.fr

- ↑ Graves, Algernon (1905). The Royal Academy of Arts - A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and their work from its foundation in 1769 to 1904. Vol. 2. London: Henri Graves and C. Ltd. p. 96.

- ↑ Anon. (25 May 1884). "Last Words on the Exhibitions". Lloyd's Weekly London Newspaper. p. 5.

- ↑ Anon. (2 May 1885). "The Grosvenor Gallery". The Era. p. 13.

- ↑ Anon. (2 May 1894). "Paris Art Schools, II - The Acadèmie Colarossi". The Sketch: A Journal of Art and Actuality. London: 25–26.

- ↑ Anon. (6 October 1889). "Touching up the Artist". Buffalo Morning Express. Buffalo, New York, USA. pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Anon. (1893). Annuaire de l'Association des Artistes peintres, sculpteurs, architectes, graveurs et dessinateurs (in French). Paris, France: L'Association des Artistes. p. 98.

- ↑ Anon. (30 June 1893). "Sport Vélocipédique". Le Rappel (in French). p. 3.

- ↑ Anon. (6 July 1893). "Course D'Artistes". Veloce Sport (in French). pp. 606–607.

- ↑ de Villemont, F. (13 July 1895). "Cyclisme". Gil Blas (in French). Paris, France. p. 4.

- ↑ Anon. (7 July 1895). "Course des Trois Arts". Le Journal (in French). p. 4.

- ↑ Anon. (14 July 1893). "Sport vélocipédique". Le Rappel (in French). p. 3.

- ↑ Anon. (8 July 1894). "Course de Cyclisme". L'Echo de Paris (in French). p. 4.

- ↑ Anon. (31 January 1894). "Cyclisme". Gil Blas (in French). p. 4. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ↑ Anon. (2 July 1895). "Tout le monde est cycliste…". Le Journal (in French). p. 1.

- ↑ Adhémar, Jean (1949). Inventaire du Fonds Français après 1800 (in French). Vol. 5, Cidoine–Daumier. Paris, France: Bibliothèque nationale, Département des Estampes et de la Photographie. p. 78.

- ↑ Anon. (1 June 1896). "Sport Vélopédique". Le Gaulois (in French). p. 3.

- ↑ Vu., G. (29 June 1898). "Vélocipédie". L'Intransigeant (in French). p. 3.

- ↑ Burke, Carolyn (1997). Becoming Modern - The Life of Mina Loy. University of California Press. p. 76.

- ↑ Anon. (29 June 1902). "Art Schools of Paris". Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 8.

- ↑ Anon. (16 April 1910). "Paris Letter". American Art News. Vol. VIII, no. 27. p. 7.

- ↑ Anon. (19 March 1910). "Académie Colarossi". Le Gaulois (in French). Paris, France. p. 4.

- ↑ Anon. (31 March 1910). "Letters to the Editor from Herald Readers. Which Rich American Can Do This?". The New York Herald. Paris. p. 8.

- ↑ Anon. (25 April 1910). "VENTES". Le Courrier - Journal quotidien; Feuille Officielle d'Annonces Judiciaires et Légales (in French). Paris, France: 10–11 – via Bibliothèque Nationale de France - Gallica.

- ↑ Anon. (22 November 1911). "Les Arts". Le Gil Blas (in French). p. 3.

- ↑ Muller, Pierre (7 January 1912). "Les Arts - Une visite chez Colarossi". Le Gil Blas (in French). p. 4.

- ↑ Anon. (5 July 1912). "La Fête de l'Indépendance américaine". Le Gil Blas (in French). p. 2.

- ↑ Anon. (2 June 1913). "American Quartier Latin". The New York Herald. Paris. p. 4. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ↑ http://montmartre-montparnasse.artdecoceramicglasslight.com/english-version-1/schools-academies/colarossi-academy - "The school closes in the 1930s. Shortly before, Mrs. Colarossi had burned the archives of the institution, in retaliation for the infidelities of her husband." https://www.artline.ro/Academie-Colarossi-and-Academie-Julian-16634-2-n.html - "Unfortunately, by the beginning of the 20th century, the school had lost most of its fame and was closed down by 1920, by the widow of Colarossi. She also destroyed much of the archives, unfortunatelly."

- ↑ Anon. (3 March 1946). "L'Art à 10 frs la Séance … à Montparnasse". V - magazine illustré du Mouvement de Libération Nationale (France) (in French): 13.

- ↑ "Écoles d'Art". Air-France Revue (in French) (23): 15–16. 1958.

- ↑ Colarossi, Maria. Actes de l'État Civil, Actes de décès de la commune de Sceaux pour l'an 1913, No 44, Document E_NUM_SCE_D1913, https://archives.hauts-de-seine.fr