Flocking is the process of depositing many small fiber particles (called flock) onto a surface. It can also refer to the texture produced by the process, or to any material used primarily for its flocked surface. Flocking of an article can be performed for the purpose of increasing its value. It can also be performed for functional reasons including insulation, slip-or-grip friction, retention of a liquid film, and low reflectivity.

Uses

Flocking is used in many ways. One example is in model building, where a grassy texture may be applied to a surface to make it look more realistic. Similarly, it is used by model car builders to get a scale carpet effect. Another use is on a Christmas tree, which may be flocked with a fluffy white spray to simulate snow. Other things may be flocked to give them a texture similar to velvet, velveteen, or velour, such as t-shirts, wallpaper, gift/jewelry boxes, and upholstery.

Besides the application of velvety coatings to surfaces and objects there exist various flocking techniques as a means of color and product design. They range from screen printing to modern digital printing in order to refine for instance fabric, clothes or books by multicolor patterns. Presently, the exploration of the flock phenomenon can be seen in the fine arts. Artist Electric Coffin is known for their many colorful flocked works, including a 50-foot piece in Facebook's Seattle headquarters.[1]

Flocking in the automotive industry is used for decorative purposes and may be applied to a number of different materials. Many rally cars also have a flocked dashboard to cut down on the sun reflecting through the windscreen. A view on the present state-of-the-art of flocking can be found in the first international exhibition "Flockage: the flock phenomenon" in the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum in Bournemouth.[2]

In the photographic industry, flocking is one method used to reduce the reflectivity of surfaces, including the insides of some bellows and lens hoods. It is also used to produce light-tight passages for film such as in 135 film cartridges.

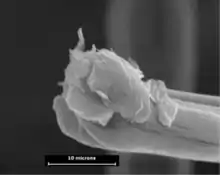

Flock consists of synthetic fibers that look like tiny hairs. Flock print feels somewhat velvet and a bit elevated. The length of the fibers can vary in thickness which co-determines the appearance of the flocked product. Thin fibers produce a soft velvety surface while thicker fibers produce a more bristle-like surface.

Flocked fabrics

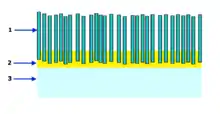

Flocking in fabrics is a method of creating another surface, imitating a piled one. In flocking, fibers or a layer are deposited over a base layer with the help of adhesive. Flocking in fabrics is possible all over the surface or in a localized area as well. Flocking as a decorative art dates back to the 14th century when short silk fibers were deposited on freshly painted walls.[3]

Flock fibers

Flock fibers are the short fibers that are used in flocking.[3]

Process

Flocking is defined as the application of fine particles to adhesive-coated surfaces, usually by the application of a high-voltage electric field. In a flocking machine the "flock" is given a negative charge whilst the substrate is earthed. Flock material flies vertically onto the substrate attaching to previously applied glue. A number of different substrates can be flocked including textiles, fabric, woven fabric, paper, PVC, sponge, toys, and automotive plastic.

The majority of flocking done worldwide uses finely cut natural or synthetic fibers. A flocked finish imparts a decorative and/or functional characteristic to the surface. The variety of materials that are applied to numerous surfaces through different flocking methods creates a wide range of end products. The flocking process is used on items ranging from retail consumer goods to products with high technology military applications.

History

Historians write that flocking can be traced back to circa 1000 B.C.E., when the Chinese used resin glue to bond natural fibers to fabrics. Fiber dust was strewn onto adhesive coated surfaces to produce flocked wall coverings in Germany during the Middle Ages.

Health issues

Flocking can expose workers to small nylon particulates, which inhaled can cause flock worker's lung, a type of interstitial lung disease. Other exposure in the flocking industry can include acrylic adhesives, ammonium ether of potato starch, heat transfer oil, tannic acid, and zeolite.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ "So Many Likes - City Arts Magazine". City Arts Magazine. 2017-03-21. Retrieved 2018-09-29.

- ↑ "For the Love of Flock – Flocking Lovely!". Free Gallery Talk. Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum. May 9, 2008. Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- 1 2 Kadolph, Sara J. (1998). Textiles. Internet Archive. Upper Saddle River, N.J. : Merrill. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-13-494592-7.

- ↑ Kern, David J.; Crausman, Robert S. (19 July 2013). "Flock worker's lung". UpToDate.