Fly-by-wire (FBW) is a system that replaces the conventional manual flight controls of an aircraft with an electronic interface. The movements of flight controls are converted to electronic signals transmitted by wires, and flight control computers determine how to move the actuators at each control surface to provide the ordered response. It can use mechanical flight control backup systems (like the Boeing 777) or use fully fly-by-wire controls.[1]

Improved fully fly-by-wire systems interpret the pilot's control inputs as a desired outcome and calculate the control surface positions required to achieve that outcome; this results in various combinations of rudder, elevator, aileron, flaps and engine controls in different situations using a closed feedback loop. The pilot may not be fully aware of all the control outputs acting to affect the outcome, only that the aircraft is reacting as expected. The fly-by-wire computers act to stabilize the aircraft and adjust the flying characteristics without the pilot's involvement, and to prevent the pilot from operating outside of the aircraft's safe performance envelope.[2][3]

Rationale

Mechanical and hydro-mechanical flight control systems are relatively heavy and require careful routing of flight control cables through the aircraft by systems of pulleys, cranks, tension cables and hydraulic pipes. Both systems often require redundant backup to deal with failures, which increases weight. Both have limited ability to compensate for changing aerodynamic conditions. Dangerous characteristics such as stalling, spinning and pilot-induced oscillation (PIO), which depend mainly on the stability and structure of the aircraft concerned rather than the control system itself, are dependent on the pilot's actions.[4]

The term "fly-by-wire" implies a purely electrically signaled control system. It is used in the general sense of computer-configured controls, where a computer system is interposed between the operator and the final control actuators or surfaces. This modifies the manual inputs of the pilot in accordance with control parameters.[2]

Side-sticks or conventional flight control yokes can be used to fly FBW aircraft.[5]

Weight saving

A FBW aircraft can be lighter than a similar design with conventional controls. This is partly due to the lower overall weight of the system components and partly because the natural stability of the aircraft can be relaxed (slightly for a transport aircraft; more for a maneuverable fighter), which means that the stability surfaces that are part of the aircraft structure can therefore be made smaller. These include the vertical and horizontal stabilizers (fin and tailplane) that are (normally) at the rear of the fuselage. If these structures can be reduced in size, airframe weight is reduced. The advantages of FBW controls were first exploited by the military and then in the commercial airline market. The Airbus series of airliners used full-authority FBW controls beginning with their A320 series, see A320 flight control (though some limited FBW functions existed on A310).[6] Boeing followed with their 777 and later designs.

Basic operation

Closed-loop feedback control

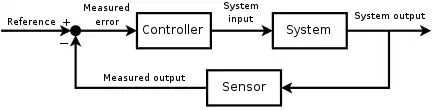

A pilot commands the flight control computer to make the aircraft perform a certain action, such as pitch the aircraft up, or roll to one side, by moving the control column or sidestick. The flight control computer then calculates what control surface movements will cause the plane to perform that action and issues those commands to the electronic controllers for each surface.[1] The controllers at each surface receive these commands and then move actuators attached to the control surface until it has moved to where the flight control computer commanded it to. The controllers measure the position of the flight control surface with sensors such as LVDTs.[7]

Automatic stability systems

Fly-by-wire control systems allow aircraft computers to perform tasks without pilot input. Automatic stability systems operate in this way. Gyroscopes and sensors such as accelerometers are mounted in an aircraft to sense rotation on the pitch, roll and yaw axes. Any movement (from straight and level flight for example) results in signals to the computer, which can automatically move control actuators to stabilize the aircraft.[3]

Safety and redundancy

While traditional mechanical or hydraulic control systems usually fail gradually, the loss of all flight control computers immediately renders the aircraft uncontrollable. For this reason, most fly-by-wire systems incorporate either redundant computers (triplex, quadruplex etc.), some kind of mechanical or hydraulic backup or a combination of both. A "mixed" control system with mechanical backup feedbacks any rudder elevation directly to the pilot and therefore makes closed loop (feedback) systems senseless.[1]

Aircraft systems may be quadruplexed (four independent channels) to prevent loss of signals in the case of failure of one or even two channels. High performance aircraft that have fly-by-wire controls (also called CCVs or Control-Configured Vehicles) may be deliberately designed to have low or even negative stability in some flight regimes – rapid-reacting CCV controls can electronically stabilize the lack of natural stability.[3]

Pre-flight safety checks of a fly-by-wire system are often performed using built-in test equipment (BITE). A number of control movement steps can be automatically performed, reducing workload of the pilot or groundcrew and speeding up flight-checks.

Some aircraft, the Panavia Tornado for example, retain a very basic hydro-mechanical backup system for limited flight control capability on losing electrical power; in the case of the Tornado this allows rudimentary control of the stabilators only for pitch and roll axis movements.[8]

History

Servo-electrically operated control surfaces were first tested in the 1930s on the Soviet Tupolev ANT-20.[9] Long runs of mechanical and hydraulic connections were replaced with wires and electric servos.

In 1934, Karl Otto Altvater filed a patent about the automatic-electronic system, which flared the aircraft, when it was close to the ground.[10]

In 1941, an engineer from Siemens, Karl Otto Altvater developed and tested the first fly-by-wire system for the Heinkel He 111, in which the aircraft was fully controlled by electronic impulses.[11]

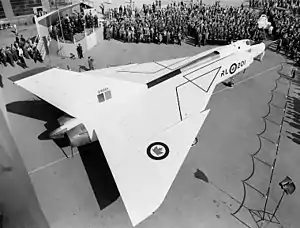

The first non-experimental aircraft that was designed and flown (in 1958) with a fly-by-wire flight control system was the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow,[12][13] a feat not repeated with a production aircraft (though the Arrow was cancelled with five built) until Concorde in 1969, which became the first fly-by-wire airliner. This system also included solid-state components and system redundancy, was designed to be integrated with a computerised navigation and automatic search and track radar, was flyable from ground control with data uplink and downlink, and provided artificial feel (feedback) to the pilot.[13]

The first electronic fly-by-wire testbed operated by the U.S. Air Force was a Boeing B-47E Stratojet (Ser. No. 53-2280)[14]

The first pure electronic fly-by-wire aircraft with no mechanical or hydraulic backup was the Apollo Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV), first flown in 1968.[15] This was preceded in 1964 by the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) which pioneered fly-by-wire flight with no mechanical backup.[16] Control was through a digital computer with three analog redundant channels. In the USSR, the Sukhoi T-4 also flew. At about the same time in the United Kingdom a trainer variant of the British Hawker Hunter fighter was modified at the British Royal Aircraft Establishment with fly-by-wire flight controls[17] for the right-seat pilot.

In the UK the two seater Avro 707C was flown with a Fairey system with mechanical backup[18] in the early to mid-60s. The program was curtailed when the air-frame ran out of flight time.[17]

In 1972, the first digital fly-by-wire fixed-wing aircraft without a mechanical backup[19] to take to the air was an F-8 Crusader, which had been modified electronically by NASA of the United States as a test aircraft; the F-8 used the Apollo guidance, navigation and control hardware.[20]

The Airbus A320 began service in 1988 as the first airliner with digital fly-by-wire controls.[21]

Analog systems

All "fly-by-wire" flight control systems eliminate the complexity, the fragility and the weight of the mechanical circuit of the hydromechanical or electromechanical flight control systems – each being replaced with electronic circuits. The control mechanisms in the cockpit now operate signal transducers, which in turn generate the appropriate electronic commands. These are next processed by an electronic controller—either an analog one, or (more modernly) a digital one. Aircraft and spacecraft autopilots are now part of the electronic controller.

The hydraulic circuits are similar except that mechanical servo valves are replaced with electrically controlled servo valves, operated by the electronic controller. This is the simplest and earliest configuration of an analog fly-by-wire flight control system. In this configuration, the flight control systems must simulate "feel". The electronic controller controls electrical feel devices that provide the appropriate "feel" forces on the manual controls. This was used in Concorde, the first production fly-by-wire airliner.[lower-alpha 1]

Digital systems

A digital fly-by-wire flight control system can be extended from its analog counterpart. Digital signal processing can receive and interpret input from multiple sensors simultaneously (such as the altimeters and the pitot tubes) and adjust the controls in real time. The computers sense position and force inputs from pilot controls and aircraft sensors. They then solve differential equations related to the aircraft's equations of motion to determine the appropriate command signals for the flight controls to execute the intentions of the pilot.[23]

The programming of the digital computers enable flight envelope protection. These protections are tailored to an aircraft's handling characteristics to stay within aerodynamic and structural limitations of the aircraft. For example, the computer in flight envelope protection mode can try to prevent the aircraft from being handled dangerously by preventing pilots from exceeding preset limits on the aircraft's flight-control envelope, such as those that prevent stalls and spins, and which limit airspeeds and g forces on the airplane. Software can also be included that stabilize the flight-control inputs to avoid pilot-induced oscillations.[24]

Since the flight-control computers continuously feedback the environment, pilot's workloads can be reduced.[24] This also enables military aircraft with relaxed stability. The primary benefit for such aircraft is more maneuverability during combat and training flights, and the so-called "carefree handling" because stalling, spinning and other undesirable performances are prevented automatically by the computers. Digital flight control systems enable inherently unstable combat aircraft, such as the Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk and the Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit flying wing to fly in usable and safe manners.[23]

Legislation

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) of the United States has adopted the RTCA/DO-178C, titled "Software Considerations in Airborne Systems and Equipment Certification", as the certification standard for aviation software. Any safety-critical component in a digital fly-by-wire system including applications of the laws of aeronautics and computer operating systems will need to be certified to DO-178C Level A or B, depending on the class of aircraft, which is applicable for preventing potential catastrophic failures.[25]

Nevertheless, the top concern for computerized, digital, fly-by-wire systems is reliability, even more so than for analog electronic control systems. This is because the digital computers that are running software are often the only control path between the pilot and aircraft's flight control surfaces. If the computer software crashes for any reason, the pilot may be unable to control an aircraft. Hence virtually all fly-by-wire flight control systems are either triply or quadruply redundant in their computers and electronics. These have three or four flight-control computers operating in parallel and three or four separate data buses connecting them with each control surface.

Redundancy

The multiple redundant flight control computers continuously monitor each other's output. If one computer begins to give aberrant results for any reason, potentially including software or hardware failures or flawed input data, then the combined system is designed to exclude the results from that computer in deciding the appropriate actions for the flight controls. Depending on specific system details there may be the potential to reboot an aberrant flight control computer, or to reincorporate its inputs if they return to agreement. Complex logic exists to deal with multiple failures, which may prompt the system to revert to simpler back-up modes.[23][24]

In addition, most of the early digital fly-by-wire aircraft also had an analog electrical, mechanical, or hydraulic back-up flight control system. The Space Shuttle had, in addition to its redundant set of four digital computers running its primary flight-control software, a fifth back-up computer running a separately developed, reduced-function, software flight-control system – one that could be commanded to take over in the event that a fault ever affected all of the computers in the other four. This back-up system served to reduce the risk of total flight-control-system failure ever happening because of a general-purpose flight software fault that had escaped notice in the other four computers.[1][23]

Efficiency of flight

For airliners, flight-control redundancy improves their safety, but fly-by-wire control systems, which are physically lighter and have lower maintenance demands than conventional controls also improve economy, both in terms of cost of ownership and for in-flight economy. In certain designs with limited relaxed stability in the pitch axis, for example the Boeing 777, the flight control system may allow the aircraft to fly at a more aerodynamically efficient angle of attack than a conventionally stable design. Modern airliners also commonly feature computerized Full-Authority Digital Engine Control systems (FADECs) that control their jet engines, air inlets, fuel storage and distribution system, in a similar fashion to the way that FBW controls the flight control surfaces. This allows the engine output to be continually varied for the most efficient usage possible.[26]

The second generation Embraer E-Jet family gained a 1.5% efficiency improvement over the first generation from the fly-by-wire system, which enabled a reduction from 280 ft.² to 250 ft.² for the horizontal stabilizer on the E190/195 variants.[27]

Airbus/Boeing

Airbus and Boeing differ in their approaches to implementing fly-by-wire systems in commercial aircraft. Since the Airbus A320, Airbus flight-envelope control systems always retain ultimate flight control when flying under normal law and will not permit the pilots to violate aircraft performance limits unless they choose to fly under alternate law.[28] This strategy has been continued on subsequent Airbus airliners.[29][30] However, in the event of multiple failures of redundant computers, the A320 does have a mechanical back-up system for its pitch trim and its rudder, the Airbus A340 has a purely electrical (not electronic) back-up rudder control system and beginning with the A380, all flight-control systems have back-up systems that are purely electrical through the use of a "three-axis Backup Control Module" (BCM).[31]

Boeing airliners, such as the Boeing 777, allow the pilots to completely override the computerised flight-control system, permitting the aircraft to be flown outside of its usual flight-control envelope.

Applications

- Concorde was the first production fly-by-wire aircraft with analogue control.

- The McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 was the first production aircraft to use digital fly-by-wire controls.

- The Space Shuttle orbiter had an all-digital fly-by-wire control system. This system was first exercised (as the only flight control system) during the glider unpowered-flight "Approach and Landing Tests" that began on the Space Shuttle Enterprise during 1977.[32]

- Launched into production during 1984, the Airbus Industries Airbus A320 became the first airliner to fly with an all-digital fly-by-wire control system.[33]

- With its launch in 1993 the Boeing C-17 Globemaster III became the first fly-by-wire military transport aircraft.[34]

- In 2005, the Dassault Falcon 7X became the first business jet with fly-by-wire controls.[35]

- A fully digital fly-by-wire without a closed feedback loop was integrated 2002 in the first generation Embraer E-Jet family. By closing the loop (feedback), the second generation Embraer E-Jet family gained a 1.5% efficiency improvement in 2016.[27]

Engine digital control

The advent of FADEC (Full Authority Digital Engine Control) engines permits operation of the flight control systems and autothrottles for the engines to be fully integrated. On modern military aircraft other systems such as autostabilization, navigation, radar and weapons system are all integrated with the flight control systems. FADEC allows maximum performance to be extracted from the aircraft without fear of engine misoperation, aircraft damage or high pilot workloads.

In the civil field, the integration increases flight safety and economy. Airbus fly-by-wire aircraft are protected from dangerous situations such as low-speed stall or overstressing by flight envelope protection. As a result, in such conditions, the flight control systems commands the engines to increase thrust without pilot intervention. In economy cruise modes, the flight control systems adjust the throttles and fuel tank selections precisely. FADEC reduces rudder drag needed to compensate for sideways flight from unbalanced engine thrust. On the A330/A340 family, fuel is transferred between the main (wing and center fuselage) tanks and a fuel tank in the horizontal stabilizer, to optimize the aircraft's center of gravity during cruise flight. The fuel management controls keep the aircraft's center of gravity accurately trimmed with fuel weight, rather than drag-inducing aerodynamic trims in the elevators.

Further developments

Fly-by-optics

.jpg.webp)

Fly-by-optics is sometimes used instead of fly-by-wire because it offers a higher data transfer rate, immunity to electromagnetic interference and lighter weight. In most cases, the cables are just changed from electrical to optical fiber cables. Sometimes it is referred to as "fly-by-light" due to its use of fiber optics. The data generated by the software and interpreted by the controller remain the same. Fly-by-light has the effect of decreasing electro-magnetic disturbances to sensors in comparison to more common fly-by-wire control systems. The Kawasaki P-1 is the first production aircraft in the world to be equipped with such a flight control system.[36]

Power-by-wire

Having eliminated the mechanical transmission circuits in fly-by-wire flight control systems, the next step is to eliminate the bulky and heavy hydraulic circuits. The hydraulic circuit is replaced by an electrical power circuit. The power circuits power electrical or self-contained electrohydraulic actuators that are controlled by the digital flight control computers. All benefits of digital fly-by-wire are retained since the power-by-wire components are strictly complementary to the fly-by-wire components.

The biggest benefits are weight savings, the possibility of redundant power circuits and tighter integration between the aircraft flight control systems and its avionics systems. The absence of hydraulics greatly reduces maintenance costs. This system is used in the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II and in Airbus A380 backup flight controls. The Boeing 787 and Airbus A350 also incorporate electrically powered backup flight controls which remain operational even in the event of a total loss of hydraulic power.[37]

Fly-by-wireless

Wiring adds a considerable amount of weight to an aircraft; therefore, researchers are exploring implementing fly-by-wireless solutions. Fly-by-wireless systems are very similar to fly-by-wire systems, however, instead of using a wired protocol for the physical layer a wireless protocol is employed.

In addition to reducing weight, implementing a wireless solution has the potential to reduce costs throughout an aircraft's life cycle. For example, many key failure points associated with wire and connectors will be eliminated thus hours spent troubleshooting wires and connectors will be reduced. Furthermore, engineering costs could potentially decrease because less time would be spent on designing wiring installations, late changes in an aircraft's design would be easier to manage, etc.[38]

Intelligent flight control system

A newer flight control system, called intelligent flight control system (IFCS), is an extension of modern digital fly-by-wire flight control systems. The aim is to intelligently compensate for aircraft damage and failure during flight, such as automatically using engine thrust and other avionics to compensate for severe failures such as loss of hydraulics, loss of rudder, loss of ailerons, loss of an engine, etc. Several demonstrations were made on a flight simulator where a Cessna-trained small-aircraft pilot successfully landed a heavily damaged full-size concept jet, without prior experience with large-body jet aircraft. This development is being spearheaded by NASA Dryden Flight Research Center.[39] It is reported that enhancements are mostly software upgrades to existing fully computerized digital fly-by-wire flight control systems. The Dassault Falcon 7X and Embraer Legacy 500 business jets have flight computers that can partially compensate for engine-out scenarios by adjusting thrust levels and control inputs, but still require pilots to respond appropriately.[40]

See also

- Index of aviation articles

- Aircraft flight control system

- Air France Flight 296Q

- Drive by wire

- Dual control (aviation)

- Flight control modes

- MIL-STD-1553, a standard data bus for fly-by-wire

- Relaxed stability

Note

References

- 1 2 3 4 Fly by Wire Flight Control Systems Sutherland

- 1 2 Crane, Dale: Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition, page 224. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997. ISBN 1-56027-287-2

- 1 2 3 "Respect the unstable – Berkeley Center for Control and Identification" (PDF).

- ↑ McRuer, Duane T. (July 1995). "Pilot Induced Oscillations and Human Dynamic Behavior" (PDF). ntrs.nasa.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2021.

- ↑ Cox, John (30 March 2014). "Ask the Captain: What does 'fly by wire' mean?". USA Today. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ↑ Dominique Brière, Christian Favre, Pascal Traverse, Electrical Flight Controls, From Airbus A320/330/340 to Future Military Transport Aircraft: A Family of Fault-Tolerant Systems, chapitre 12 du Avionics Handbook, Cary Spitzer ed., CRC Press 2001, ISBN 0-8493-8348-X

- ↑ "Flight Control Surfaces Sensors and Switches – Honeywell". sensing.honeywell.com. 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ↑ The Birth of a Tornado. Royal Air Force Historical Society. 2002. pp. 41–43.

- ↑ One of the history page (in Russian), PSC "Tupolev", archived from the original on 10 January 2011

- ↑ Patent Hoehensteuereinrichtung zum selbsttaetigen Abfangen von Flugzeugen im Sturzflug, Patent Nr. DE619055 C vom 11. Januar 1934.

- ↑ The History of German Aviation Kurt Tank Focke-Wulfs Designer and Test Pilot by Wolfgang Wagner page 122.

- ↑ W. (Spud) Potocki, quoted in The Arrowheads, Avro Arrow: the story of the Avro Arrow from its evolution to its extinction, pages 83–85. Boston Mills Press, Erin, Ontario, Canada 2004 (originally published 1980). ISBN 1-55046-047-1.

- 1 2 Whitcomb, Randall L. Cold War Tech War: The Politics of America's Air Defense. Apogee Books, Burlington, Ontario, Canada 2008. Pages 134, 163. ISBN 978-1-894959-77-3

- ↑ "The National Museum of Nuclear Science & History Heritage Park". nuclearmuseum.org. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ↑ "NASA – Lunar Landing Research Vehicle". nasa.gov. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ "1 NEIL_ARMSTRONG.mp4 (Part Two of Ottinger LLRV Lecture)". ALETROSPACE. 8 January 2011. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2018 – via YouTube.

- 1 2 "RAE Electric Hunter", Flight International, p. 1010, 28 June 1973, archived from the original on 5 March 2016

- ↑ "Fairey fly-by-wire", Flight International, 10 August 1972, archived from the original on 6 March 2016

- ↑ "Fly-by-wire for combat aircraft", Flight International, p. 353, 23 August 1973, archived from the original on 21 November 2018

- ↑ NASA F-8, nasa.gov, retrieved 3 June 2010

- ↑ Learmount, David (20 February 2017). "How A320 changed the world for commercial pilots". Flight International. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ "Dowty wins vectored thrust contract". Flight International. 5 April 1986. p. 40. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Avionics Handbook" (PDF). davi.ws. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Airbus A320/A330/A340 Electrical Flight Controls: A Family of Fault-Tolerant Systems" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009.

- ↑ Explorer, Aviation. "Fly-By-Wire Aircraft Facts History Pictures and Information". aviationexplorer.com. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ Federal Aviation Administration (29 June 2001). "Full Authority Digital Engine Control" (PDF). Compliance Criteria For 14 CFR §33.28, Aircraft Engines, Electrical And Electronic Engine Control Systems. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 June 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- 1 2 Norris, Guy (5 September 2016). "Embraer E2 Certification Tests Set to Accelerate". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Aviation Week. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ↑ "Air France 447 Flight-Data Recorder Transcript – What Really Happened Aboard Air France 447". Popular Mechanics. 6 December 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ Briere D. and Traverse, P. (1993) "Airbus A320/A330/A340 Electrical Flight Controls: A Family of Fault-Tolerant Systems Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine" Proc. FTCS, pp. 616–623.

- ↑ North, David. (2000) "Finding Common Ground in Envelope Protection Systems". Aviation Week & Space Technology, 28 Aug, pp. 66–68.

- ↑ Le Tron, X. (2007) A380 Flight Control Overview Presentation at Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, 27 September 2007

- ↑ Klinar, Walter J.; Saldana, Rudolph L.; Kubiak, Edward T.; Smith, Emery E.; Peters, William H.; Stegall, Hansel W. (1 August 1975). "Space Shuttle Flight Control System". IFAC Proceedings Volumes. 8 (1): 302–310. doi:10.1016/S1474-6670(17)67482-2. ISSN 1474-6670.

- ↑ Ian Moir; Allan G. Seabridge; Malcolm Jukes (2003). Civil Avionics Systems. London (iMechE): Professional Engineering Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-86058-342-3.

- ↑ "C-17 Globemaster III Archives". Air & Space Forces Magazine. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ↑ "Pilot Report on Falcon 7X Fly-By-Wire Control System". Aviation Week & Space Technology. 3 May 2010.

- ↑ "Japans P1 leads defence export drive". iiss.org. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ "A350 XWB family & technologies" (PDF).

- ↑ ""Fly-by-Wireless": A Revolution in Aerospace Vehicle Architecture for Instrumentation and Control" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2021.

- ↑ Intelligent Flight Control System. IFCS Fact Sheet. NASA. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ↑ Flying Magazine Fly by Wire. "Fly by Wire: Fact versus Science Fiction". Flying Magazine. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

External links

- "Fly-by-wire" a 1972 Flight article archive version

_Farnborough_SEP86_(12609347665).jpg.webp)