| Southern blushwood | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fontainea venosa in Coffs Harbour Botanic Gardens | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malpighiales |

| Family: | Euphorbiaceae |

| Genus: | Fontainea |

| Species: | F. venosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Fontainea venosa | |

Fontainea venosa, also commonly known as southern blushwood,[2] veiny fontainea,[3] Queensland fontainea and formerly named as Bahrs scrub fontainea[4] is a rare rainforest shrub or tree of the family Euphorbiaceae. It is found in southeastern Queensland, Australia, extending from Boyne Valley to Cedar Creek and is considered vulnerable due to several contributing threats (fire, urban development, and weed infestation).[5][6] The total population size is around 200 plants.[7][8]

Studies regarding genetic variability within Fontainea species through RAPD analysis had shown that F. venosa represents the most divergent taxonomic unit and was the only clearly distinct species.[9] The Multigene CYP450 in Fontainea venosa is also distinct from other Fontainea species.[10] F. venosa also shares similar genetics to Fontainea picrosperma and may contain the drug EBC-46, which has been found to be effective for patients coping with cancer.[11]

Description

Fontainea venosa is a shrub or tree that normally grows to approximately 18 m tall. It has leathery and hairless elliptic to oblanceolate leaves, with its wide roundest part near its apex and narrowest near its base. The leaves range from 5 to 9 cm long and 2 to 5 cm wide. Veins on the leaves are rather apparent and visible. Each leaf has a base with a pair of glands with uplifted edges. Its leaf stalk or petiole ranges from 3 to 13 mm long and is slightly inflated at its base.[5][6]

F. venosa's flowering phase has been recorded to occur mainly in January, February, April, May, June, August and October.[5] Its apical white-scented male and female flowers grow on separate trees. Female flowers are apical and often occur in clusters of 1 to 4. Each female flower has 0.5 mm long styles crowning a big smooth ovary and a 0.7 mm long disc. Male flowers are botryose, apical and commonly have 20 to 24 stamens and approximately 4 to 6 petals. Male flowers’ calyx lobes range from three to five and are "hairy" on the outside and smooth on the inside. Male flowers’ petals are oval, have soft hairs on their surfaces, and measure from 3 to 5 mm long and 3 mm wide.[6][12][13]

Its fruiting season normally occurs throughout the year except May and November and its fruits usually ripen across August, September and October.[5] Its fruits have an orange to yellow colour and are spherical, 20 to 25 mm long and 17 to 26 mm wide. The endocarp, which normally ranges from 1.5 to 2.5 cm long and 1 to 2 cm wide, surrounds a single seed that lies at the core of the fruit.[5][6]

Taxonomy

F. venosa was first formally described in 1985 by Laurence W. Jessup and Gordon P. Guymer in the journal Austrobaileya from specimens collected at Bahr's Hill, south of Beenleigh in 1984.[14][15]

Phylogeny

A study on the genetic variability and evolutionary relationships within the genus Fontainea (Fontainea venosa, Fontainea oraria, Fontainea australis, Fontainea rostrata, and Fontainea venosa) using Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis, and molecular phylogenetic study based on cpDNA and nrDNA, found that F. venosa was the most divergent taxonomic unit and distinct species.[9]

Direct sequencing of selected cpDNA and nrDNA within the genus affirmed four distinct sequence groups, of which the third sequence is unique to F. venosa, while other sequences are shared within the genus. F. venosa derived the majority of informative changes with a total of 12 unique nucleotide substitutions. Other substitutions were shared between species. The study evinced that F. venosa was the sole distinct species within the genus, as F. australis was identical to F. rostrata. It was not possible to differentiate F. oraria and F. australis.[9]

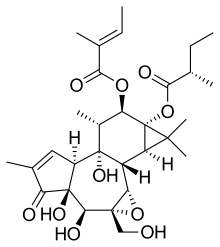

A study that examined the presence of Cytochrome P450s (CYP450s), vital enzymes for biosynthesis of physiologically essential compounds involved in the catalysis reactions of plant growth and development via metabolome analysis, showed that Fontainea species have a unique chemical profile compared to other plant species.[10] The result also indicated that F. picrosperma and F. venosa are closely related species and possibly share similar arrays of natural products including epoxytigliane diterpenes (EBC-46) or tigilanol tiglate.[10] While F. venosa comprises a total of 123 full-length CYP450 genes in its leaf and root tissue (65% most active in root tissue), F. picrosperma comprises 103 full-length CYP450 genes (66.2% most active in its root tissues). Both species (F. venosa and F. picrosperma) also share some clans of CYP450 genes, such as CYP71 which is classified to have a strong potential of being "key enzymes in the biosynthesis of diterpene esters of epoxy-tigliane class," for medicinal purposes. Unique putative full-length CYP45 genes were also identified only in both species (F. venosa and F. picrosperma).[10]

Distribution and habitat

F. venosa occurs in few locations in Queensland, ranging from Beenleigh North near Brisbane, alongside Koolkooron Creek in Boyne Valley, near Littlemore and to Brooyar State Forest next to Nargoorin. The species also can be found in Dawes National Park and Marys Creek State Forest.[16]

Its recorded distributional limits range from Boyne Valley (24°24'24.3"S 151°11'07.2"E) to Cedar Creek (27°49'44.3"S 153°12'13.8"E).[13] F. venosa was also recorded in Barakula State Forest and SF 124 in 1934, though the exact current presence in SF 124 to date is still unknown due to a failed retrieval in SF 124 in 1984.[5][6]

F. venosa occurs mainly in Notophyll vine forests or Araucaria microphyll vine forests and vine thickets, up to 380 meters in altitude that capture moderate orographic rainfall. It occurs on soils derived from and composing andesitic rocks, habitually along creeks or rocky outcrops.[17]

Conservation status and threats

According to the Queensland Nature Conservation Act 1992, Commonwealth Environment Protection, Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, and Nature Conservation 2006 Regulation, F. venosa is considered to be "vulnerable" — populations are threatened and declining, resulting in their long-term survival being further at risk if no protective management measure is taken.[5][6][18]

F. venosa is categorized as "under threat"[19][20] and "poorly conserved".[18] Threats include habitat destruction due to urban and agricultural development in a majority of vine forests where it naturally occurs, particularly nearby Bahr's Scrub, Beenleigh[19] and exotic weed infestation, including Rivina humilis, Lantana camara and Passiflora subpeltata, that hindered F. venosa germination and seedling growth, particularly in SF 82 (Brooyar).[21]

Stochastic events due to its fragmented and confined distribution and changed fire regimes are other potential threats to F. venosa.[5]

Protective management measures

Protective regional and local priority management actions documented by DSEWPC (2012) in supporting F. venosa recovery include: minimizing disturbance and modifications to its natural habitat by reducing land-use impacts; controlling access routes; keeping track of its known population; establishing actionable fire management strategies; and executing invasive weeds prevention and removal actions local areas.[6]

Other management actions include; assembling responsible seed collection; storage and facilitate appropriate sites for recovery; raising awareness of F. venosa to both local and regional communities, and constructing a protective buffer (0.3 ha) at least 30m away around the areas of vine forest and vine thicket where F. venosa occurs in to prevent habitat clearance.[6][12]

Current restoration initiatives

The Restoration of Belivah Creek is one of the current restoration incentives taken by Logan City Council, Queensland. Results from Geographic Information System Mapping (GIS) assessment and on-ground survey in the restoration plan will identify suitable microhabitats in Belivah Creek to introduce F. venosa while conserving its site flood mitigation and recreational functionality. Initial species will be sourced from within Belivah Creek catchment or its surrounding proximity area.[22]

F. venosa is also listed to continue to be protected and restored under the Springbrook Rescue initiative which aims to restore the critical habitat of species that contributes to the values and integrity of the Gondwana Rainforest of Australia World Heritage Area.[23]

The Mary River Recover plan priorities include mitigating various threats such as uncontrolled invasive weeds, blockage to bio-passage, and soil erosion due to the water stream and river siltation. The majority of actions taken in addressing identified threats involves a system-wide impact that improves overall system health.[24]

The project recovery plan stated that 32 plant species — including F. venosa — are endemic to Mary River and thus will be restored.[24]

Research on possible uses

Plants in the genus Fontainea, particularly F. picrosperma, had been studied to comprise a protein Kinase C-activating compound, EBC-46 now known as Tigilanol tiglate or epoxytigliane diterpenes, commonly extracted from its seed or other plant parts. According to recently published studies and current research, EBC-46, has the potential to be an anti-cancer drug with cancer destroying properties.[11]

As there is a close similarity in genetics,[10] found between F. venosa and F. picrosperma, some articles had stated that F. venosa also contains EBC-46.[2] However, no adequate studies have been published stating the presence of EBC-46 in F. venosa.

References

- ↑ "Fontainea venosa". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- 1 2 "Fontainea venosa 'Southern Blushwood' plant". Herbalistics. Logan River Branch SGAP (Qld Region) Inc. 2004.

- ↑ Mangroves to Mountains: A Field Guide to the Native Plants of South-east Queensland (revised 2008 ed.). Queensland: Logan River Branch SGAP (Qld Region) Inc. 2008.

- ↑ BaT Project: Environmental Impact Statement (PDF). Queensland Government.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wearne, L (16 February 2012). "Species Profile – Fontainea venosa". QLD Wildlife Data API. Queensland Government.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Boorsboom, Adrian Charles; Wang, Jian (1997). "Fontainea venosa Jessup & Guymer". Botanical Research – via Research Gate.

- ↑ "Fontainea venosa". Queensland Government – Department of Conservation and Science. 20 October 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ↑ "Approved conservation advice for Fontainea venosa" (PDF). Queensland Government – Department of Conservation and Science. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 Rossetto, Maurizio; McNally, Jody; Henry, Robert J.; Hunter, John; Matthes, Maria (1 September 2000). "Conservation genetics of an endangered rainforest tree (Fontainea oraria – Euphorbiaceae) and implications for closely related species". Conservation Genetics. 1 (3): 217–229. doi:10.1023/A:1011549604106. ISSN 1572-9737. S2CID 25802957.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mitu, Shahida A.; Ogbourne, Steven M.; Klein, Anne H.; Tran, Trong D.; Reddell, Paul W.; Cummins, Scott F. (December 2021). "The P450 multigene family of Fontainea and insights into diterpenoid synthesis". BMC Plant Biology. 21 (1): 191. doi:10.1186/s12870-021-02958-y. PMC 8058993. PMID 33879061.

- 1 2 Ogbourne, Steven (2014). "EBC-46, a novel cancer therapy from Queensland's tropical rainforest". University Sunshine Coast Research Conference – via USC Research Bank.

- 1 2 "Fontainea venosa". Australian Government. Canberra: Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (DSEWPC). 2012.

- 1 2 Harden, G; McDonald, B; Williams, J (2006). Rainforest Trees & Shrubs – a field guide to their identification in Victoria, New South Wales and subtropical Queensland using vegetative features. Australia: Gwen Harden Publishing. ISBN 9780977555307.

- ↑ "Fontainea venosa". APNI. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ Jessup, Laurence W.; Guymer, Gordon P. (1985). "A Revision of Fonatinea venosa Heckel (Euphorbiaceae – Cluttieae)". Austrobaileya. 2 (2): 122. JSTOR 41738658. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ Queensland Herbarium (2012). Specimen label information. Queensland Herbarium.

- ↑ BaT Project: Environmental Impact Statement(PDF) (PDF). Australia: Queensland Government.

- 1 2 Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulation 1994 (1994).Queensland Subordinate Legislation 1994 No. 474

- 1 2 Barry, S.J. & Thomas, G.T. (1994) Threatened Vascular Rainforest Plants of South- east Queensland: A Conservation Review. Unpublished report to ANCA. Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage.

- ↑ Williams, J. B.; Harden, G. J.; McDonald, W. J. F. (1984). Trees & shrubs in rainforests of New South Wales and southern Queensland. University of New England. Armidale, N.S.W: Botany Dept., University of New England. ISBN 978-0-85834-555-3.

- ↑ Forster, P.I. (1996) Pers. comm., Queensland Herbarium, Department of Environment (DoE), Brisbane.

- ↑ Logan. "Restoring Belivah Creek". Logan City Council. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ↑ "Rainforest restoration at Springbrook will help survival of threatened species". springbrookrescue.org.au. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- 1 2 "Mary River Threatened Species Recovery Plan" (PDF). Commonwealth of Australia. Australian Government. 2016.

External links

Data related to Fontainea venosa at Wikispecies

Data related to Fontainea venosa at Wikispecies