Frank H. Furness | |

|---|---|

Furness in 1901 | |

| Born | November 12, 1839 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | June 27, 1912 (aged 72) Upper Providence Township, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States Union |

| Service/ | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861-1864 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War Battle of Brandy Station Battle of Gettysburg Battle of Trevilian Station |

| Awards | Medal of Honor |

| Other work | Architect |

Frank Heyling Furness (November 12, 1839 – June 27, 1912) was an American architect of the Victorian era. He designed more than 600 buildings, most in the Philadelphia area, and is remembered for his diverse, muscular, often inordinately scaled buildings, and for his influence on the Chicago-based architect Louis Sullivan. Furness also received a Medal of Honor for bravery during the Civil War.

Toward the end of his life, his bold style fell out of fashion, and many of his significant works were demolished in the 20th century. Among his most important surviving buildings are the University of Pennsylvania Library, now the Fisher Fine Arts Library, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia, all in Philadelphia, and the Baldwin School Residence Hall in Bryn Mawr.

Early life and education

Furness was born in Philadelphia on November 12, 1839. His father, William Henry Furness, was a prominent Unitarian minister and abolitionist, and his brother, Horace Howard Furness, became America's outstanding Shakespeare scholar. Frank, however, did not attend a university and apparently did not travel to Europe. He began his architectural training in the office of John Fraser, Philadelphia, in the 1850s. He attended the École des Beaux-Arts-inspired atelier of Richard Morris Hunt in New York City, from 1859 to 1861, and again in 1865, following his military service. Furness considered himself Hunt's apprentice and was influenced by Hunt's dynamic personality and accomplished, elegant buildings. He was also influenced by the architectural concepts of the French engineer Viollet-le-Duc and the British critic John Ruskin.

.jpg.webp)

Career

Furness's first commission, Germantown Unitarian Church (1866–67, demolished ca. 1928), was a solo effort, but in 1867, he formed a partnership with Fraser, his former teacher, and George Hewitt, who had worked in the office of John Notman. The trio lasted less than five years, and its major commissions were Rodef Shalom Synagogue (1868–69, demolished) and the Lutheran Church of the Holy Communion (1870–75, demolished). In 1897, Furness designed an addition to the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society (PSFS) 1869 building which has now been incorporated into the St. James, a high-rise luxury apartment complex in the city’s Washington Square neighborhood.[1]

Following Fraser's move to Washington, D.C., to become supervising architect for the U.S. Treasury Department, the two younger men formed a partnership in 1871, and soon won the design competition for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1871–76). Louis Sullivan worked briefly as a draftsman for Furness & Hewitt (June - November 1873),[lower-alpha 1] and his later use of organic decorative motifs can be traced, at least in part, to Furness. By the beginning of 1876, Furness had broken with Hewitt, and the firm carried only his name. Hewitt and his brother William formed their own firm, G.W. & W.D. Hewitt, and became Furness's biggest competitor. In 1881, Furness promoted his chief draftsman, Allen Evans, to partner (Furness & Evans); and, in 1886, did the same for four other long-time employees.[3] The firm continued under the name Furness, Evans & Company as late as 1932, two decades after its founder's death.[4]: 251

Furness was one of the most highly paid architects of his era, and a founder of the Philadelphia Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. Over his 45-year career, he designed more than 600 buildings, including banks, office buildings, churches, and synagogues. Nearly one-third of his commissions came from railroad companies. As chief architect of the Reading Railroad, he designed about 130 stations and industrial buildings. For the Pennsylvania Railroad, he designed more than 20 structures, including the great Broad Street Station (demolished 1953) at Broad and Market Streets in Philadelphia. His 40 stations for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad included the ingenious 24th Street Station (demolished 1963) beside the Chestnut Street Bridge. His residential buildings included numerous mansions in Philadelphia and its suburbs, especially the Philadelphia Main Line and commissioned houses at the New Jersey Shore, and in Newport, Rhode Island, Bar Harbor, Maine, Washington, D.C.; New York state, and Chicago.

Furness broke from dogmatic adherence to European trends, and juxtaposed styles and elements in a forceful manner. His strong architectural will is seen in the unorthodox way he combined materials: stone, iron, glass, terra cotta, and brick. And his straightforward use of these materials, often in innovative or technologically advanced ways, reflected Philadelphia's industrial-realist culture of the post–Civil War period.

Interior design and furniture

Furness designed custom furniture for a number of his early residences and buildings. One notable commission was the 1870-1871 redesign of the interiors of elder brother Horace Howard Furness's city house, at the southwest corner of 7th and Locust Streets in Philadelphia. Work on Horace's library included elaborate Neo-Grec bookcases, a reliquary for a (supposed) death mask of William Shakespeare, and a Neo-Grec desk, now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. These pieces can be documented by drawings in Furness's sketchbooks and a letter in HHF's papers: "These bookcases were placed in position this day—February 18th 1871. They were designed by Capt. Frank Furness, and made by Daniel Pabst …"[5]

In 1873, Furness designed interiors and furniture for the Manhattan city house of Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., father of the future president. Although the house was demolished, Furness/Pabst furniture from it survives at Sagamore Hill, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the High Museum of Art, in Atlanta.[6]

Furness designed bookcases and a suite of table and armchairs for the boardroom of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, along with the lectern for its auditorium.[7]: 161 Manufacture of these is attributed to Pabst. A, c. 1875-1876 A Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts boardroom armchair is in the Victoria and Albert Museum, in London.[8]

Military service

During the American Civil War, Furness served as captain and commander of Company F, 6th Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry, also known as "Rush's Lancers". He received the Medal of Honor for his gallantry at the Battle of Trevilian Station.

Medal of Honor citation

Rank and organization: Captain, Company F, 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Place and date: At Trevilian Station, Virginia, June 12, 1864. Entered service at: Philadelphia, Pa. Birth:------. Date of issue: October 20, 1899.

Citation:

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Captain (Cavalry) Frank Furness, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 12 June 1864, while serving with Company F, 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, in action at Trevilian Station, Virginia. Captain Furness voluntarily carried a box of ammunition across an open space swept by the enemy's fire to the relief of an outpost whose ammunition had become almost exhausted, but which was thus enabled to hold its important position.[9][10]

Gettysburg monument

Twenty-five years after fighting in the Battle of Gettysburg, he designed the monument to his regiment on South Cavalry Field:

In design it is a simple granite block, as massive as a dolmen, but surrounded by a corona of bronze lances that are models of the original lances. ... [T]hey are depicted in a resting position, as if waiting to be seized at any instant and brought into battle. The sense of suspended action before the moment of the battle is all the more potent because it is rendered in stone and metal, making it perpetual. Of the hundreds of monuments at Gettysburg, Furness's is among the most haunting.[4]: 44

Personal life

Furness married Fanny Fassit in 1866, and they had four children: Radclyffe, Theodore, James, and Annis Lee. His brother-in-law, James Wilson Fassitt Jr. (1850–1892), became an architect in Furness's firm, and was promoted to partner in 1886.[7]: 86

Death

Furness died on June 27, 1912, in Idlewild, Pennsylvania, at his summer house outside Media, Pennsylvania, and was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.[11]

Rediscovery

.jpg.webp)

Following decades of neglect, during which many of Furness's most important buildings were demolished, there was a revival of interest in his work in the mid-20th century. The critic Lewis Mumford, tracing the creative forces that had influenced Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, wrote in The Brown Decades (1931): "Frank Furness was the designer of a bold, unabashed, ugly, and yet somehow healthily pregnant architecture."[12]

The architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock, in his comprehensive survey Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (revised 1963), saw beauty in that ugliness:

[O]f the highest quality, is the intensely personal work of Frank Furness (1839-1912) in Philadelphia. His building for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Broad Street was erected in 1872-76 in preparation for the Centennial Exposition. The exterior has a largeness of scale and a vigor in the detailing that would be notable anywhere, and the galleries are top-lit with exceptional efficiency. Still more original and impressive were his banks, even though they lay quite off the main line of development of commercial architecture in this period. The most extraordinary of these, and Furness's masterpiece, was the Provident Institution in Walnut [sic Chestnut] Street, built as late as 1879. This was most unfortunately demolished in the Philadelphia urban renewal campaign several years ago, but the gigantic and forceful scale of the granite membering alone should have justified its respectful preservation. No small part of Furness's historical significance lies in the fact that the young Louis Sullivan picked this office - then known as Furness & Hewitt - to work in for a short period after he left Ware's School in Boston. As Sullivan's Autobiography of an Idea testifies, the vitality and originality of Furness meant more to him than what he was taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, or later at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris.[13]

Architect and critic Robert Venturi in Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) wrote, not unadmiringly, of the National Bank of the Republic, later renamed the Philadelphia Clearing House:

The city street facade can provide a type of juxtaposed contradiction that is essentially two-dimensional. Frank Furness' Clearing House, now demolished like many of his best works in Philadelphia, contained an array of violent pressures within a rigid frame. The half-segmental arch, blocked by the submerged tower which, in turn, bisects the facade into a near duality, and the violent adjacencies of rectangles, squares, lunettes, and diagonals of contrasting sizes, compose a building seemingly held up by the buildings next door: it is an almost insane short story of a castle on a city street.[14]

On the occasion of its centennial in 1969, the Philadelphia Chapter of the American Institute of Architects memorialized Furness as its 'great architect of the past':

For designing original and bold buildings free of the prevalent Victorian academicism and imitation, buildings of such vigor that the flood of classical traditionalism could not overwhelm them, or him, or his clients ...

For shaping iron and concrete with a sensitive understanding of their particular characteristics that was unique for his time ...

For his significance as innovator-architect along with his contemporaries John Root, Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright ...

For his masterworks, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Provident Trust Company, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station, and the University of Pennsylvania Library (now renamed the Furness Building) ...

For his outstanding abilities as draftsman, teacher and inventor ...

For being a founder of the Philadelphia Chapter and of the John Stewardson Memorial Scholarship in Architecture ...

And above all, for creating architecture of imagination, decisive self-reliance, courage, and often great beauty, an architecture which to our eyes and spirits still expresses the unusual personal character, spirit and courage for which he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for bravery on a Civil War battlefield.[15]

Legacy

Furness designed custom interiors and furniture in collaboration with Philadelphia cabinetmaker Daniel Pabst. Examples are in the collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art;[16][17] the University of Pennsylvania;[18] the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia;[19] the Victoria and Albert Museum in London,[20] and elsewhere. Mark-Lee Kirk's set designs for the 1942 Orson Welles film The Magnificent Ambersons seem to be based on Furness's ornate Neo-Grec interiors of the 1870s.[4]: 108 A fictional desk designed by Furness is featured in the John Bellairs novel The Mansion in the Mist.

Furness's independence and modernist Victorian-Gothic style inspired 20th-century architects Louis Kahn and Robert Venturi. Living in Philadelphia and teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, they often visited Furness's Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts — built for the 1876 Centennial — and his University of Pennsylvania Library.

In 1973, the Philadelphia Museum of Art mounted the first retrospective of Furness's work, curated by James F. O'Gorman, George E. Thomas and Hyman Myers. Thomas, Jeffrey A. Cohen and Michael J. Lewis authored Frank Furness: The Complete Works (1991, revised 1996), with an introduction by Robert Venturi. Lewis wrote the first biography: Frank Furness: Architecture and the Violent Mind (2001).

The 2012 centenary of Furness's death was observed with exhibitions at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the University of Pennsylvania, Drexel University, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the Athenaeum of Philadelphia, the Delaware Historical Society, the First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia, and elsewhere.[21] On September 14, a Pennsylvania state historical marker was dedicated in front of Furness's boyhood home at 1426 Pine Street, Philadelphia (now Peirce College Alumni Hall). Opposite the marker is Furness's 1874-75 dormitory addition to the Pennsylvania Institute for the Deaf and Dumb, now the Furness Residence Hall of the University of the Arts.[22]

Selected architectural works

Philadelphia buildings

- Northern Savings Fund Society Building, 1871–72, with George Hewitt.[23]

- Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Broad & Cherry Streets, 1871–76, with George Hewitt.

- Parish House, Church of St. Luke and the Epiphany, 330 South 13th Street, c. 1875, with George Hewitt.

- Thomas Hockley House, 21st & St. James Streets, 1875.

- Gatehouses, Philadelphia Zoological Gardens, 1875–76.[24]

- Centennial National Bank, 33rd & Market Streets, 1876. Now Paul Peck Alumni Center, Drexel University.

- Kensington National Bank, Girard & Frankford Aves., 1877 (Now a branch of Wells Fargo).[25]

- St. Stephen's Episcopal Church transept and vestry room, 19 S 10th Street, 1879.[26]

- Knowlton (William H. Rhawn mansion), Rhawn Street & Verree Road, 1881.

- Gravers Lane Station, 200 E Gravers Lane, Chestnut Hill, 1882.[7] Philadelphia & Reading Company

- Mount Airy Station, E Gowen Ave & Devon St, Mount Airy, 1882.[7] Philadelphia & Reading Company

- Undine Barge Club, #13 Boathouse Row, 1882–83.[27]

- First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia, 2125 Chestnut Street, 1885.

- University of Pennsylvania Library, 34th Street, 1891. Now the Anne and Jerome Fisher Fine Arts Library.

- Mortuary Chapel, Mount Sinai Cemetery (Frankford), 1891–92.

- Horace Jayne House, 19th & Delancey Streets, 1895.[28]

- Girard Trust Bank, Broad & Chestnut Streets, 1907 (now The Ritz-Carlton Philadelphia) constructed for the Girard Trust Company.[29][30]

- Henry's home,[31] sole surviving building of the demolished Thomas and H. Pratt McKean townhouses, 1923 Walnut St., 1869.

- Wayne Junction station, 4481 Wayne Avenue.

Demolished Philadelphia buildings

- Germantown Unitarian Church, 1866-67[32]

- Rodef Shalom Synagogue, 1868–69.[33]

- Thomas and H. Pratt McKean townhouses, 1923-25 Walnut St., 1869, demolished 1897 and 1920s.

- Lutheran Church of the Holy Communion, 1870–75.[34]

- Guarantee Trust and Safe Deposit Company, 1875.[35]

- Brazilian Section, Main Exhibition Building, Centennial Exposition (1876).

- Church of the Redeemer for Seamen and their Families, 1878.[36]

- Provident Life & Trust Company, 1879.[37]

- Library Company of Philadelphia Building, 1879–80.[38]

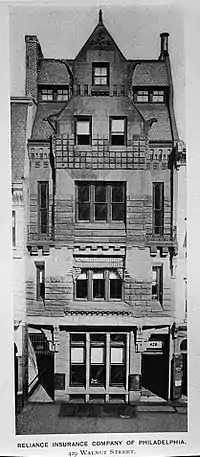

- Reliance Insurance Company Building, 1881–82.[39]

- National Bank of the Republic (later Philadelphia Clearing House), 1883–84.[40]

- Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station (24th Street Station), 1886–88.[41]

- The Cottage at the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, c 1888

- Franklin Sugar Refinery, 125 S 12th Street, c. 1895.

- Alexander J. Cassatt townhouse, 202 West Rittenhouse Square, c. 1888.

- Broad Street Station, Pennsylvania Railroad, 1892–93.[42]

- Arcade Building and pedestrian bridge to Broad Street Station, 1901–02.[43]

Buildings elsewhere

Railroad stations

- Manheim Station, Manheim, Pennsylvania, 1881, Philadelphia & Reading Company.[7]

- East Strasburg Station, Petersburg, Pennsylvania, 1882, Philadelphia & Reading Company, moved to Strasburg Railroad.

- Sunbury Station, Sunbury, Pennsylvania, 1883, Philadelphia & Reading Company.[7]

- Aberdeen Station, Aberdeen, Maryland, 1885, Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

- B&O Station, Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1887, demolished 1955, Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

- Lansdowne Station, Lansdowne, Pennsylvania, 1901, Pennsylvania Railroad.[7]

- Edgewood Station, Edgewood, Pennsylvania, 1903, Pennsylvania Railroad.[7]

- Sherwood Station, Riderwood, Maryland, 1905, Northern Central Railway.

Wilmington, Delaware

Three buildings in Wilmington, Delaware, reputed to be the largest grouping of Furness-designed railroad buildings, form the Frank Furness Railroad District.

- Water Street Station, Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, ca. 1887.[44]

- Pennsylvania Railroad Building, 1905.[45]

- French Street Station (Wilmington Station), Pennsylvania Railroad (now Amtrak), 1908.[46]

Residences

- Grubb Cottage (E. Burd Grubb Estate), Burlington, New Jersey, 1872

- Lindenshade (Horace Howard Furness house), Wallingford, Pennsylvania, 1873 (demolished 1940).[47][48]

- Fairholme (Fairman Rogers mansion), Newport, Rhode Island, 1874–1875. Its carriage house is now Jean and David W. Wallace Hall, Salve Regina University.[49]

- George Fryer cottage, Cape May, New Jersey, 1871–72; rebuilt after fire, 1878–79.[50]

- Emlen Physick house, Cape May, New Jersey, 1879.[51]

- Fairview, near Delaware City, Delaware (1880 alterations). Furness added a third story and rear wing to an 1822 farmhouse.

- Dolobran (Clement A. Griscom mansion), Haverford, Pennsylvania, 1881, circa-1888, 1894.[52]

- Lotta Crabtree Cottage, Mount Arlington, New Jersey, 1885–86.

- Idlewild (Frank Furness house), Idlewild Lane, Media, Pennsylvania (c. 1888).

- Ragged Edge (Col. Moorhead Kennedy house), Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, 1900–1901.[53]

- Judge Eugene G. Smith , Lancaster, Pennsylvania. 1890

Schools

- Williamson College of the Trades (formerly Williamson Free School of Mechanical Trades), Elwyn, Pennsylvania, original campus buildings, completed in 1889–90.[54]

- The Baldwin School (built as the second Bryn Mawr Hotel), Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, 1890.[55]

- Recitation Hall, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware, 1891.[56]

- Haverford School, Haverford, Pennsylvania, 1902.[57]

Churches

- All Hallows Church, Wyncote, Pennsylvania, 1897.[58]

- Church of Our Father, Hull's Cove, Mount Desert Island, Maine, 1890–91.[59]

- St. Michael's Protestant Episcopal Church, Birdsboro, Pennsylvania, 1884–85.[60]

Other

- New Castle Public Library, New Castle, Delaware, 1892 (now Old Library Museum, New Castle Historical Society).[61]

- Sixth Pennsylvania Cavalry (Rush's Lancers) Monument, Gettysburg Battlefield, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 1888.[62]

- Merion Cricket Club, Haverford, Pennsylvania (Allen Evans, Furness's partner, is credited with the design), 1896–97.[63]

Gallery

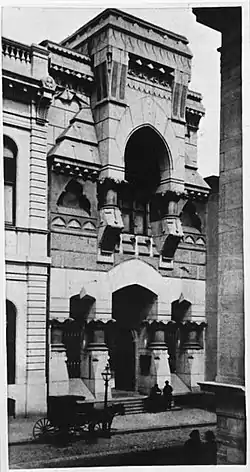

Thomas and H. Pratt McKean Townhouses, 1923-25 Walnut St., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1869, demolished 1897 and 1920s).

Thomas and H. Pratt McKean Townhouses, 1923-25 Walnut St., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1869, demolished 1897 and 1920s). Lindenshade (Horace Howard Furness house), Wallingford, Pennsylvania (c. 1873, demolished 1940). A country house built for the architect's brother, it was later greatly expanded.

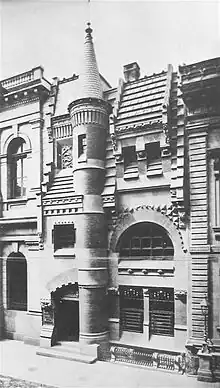

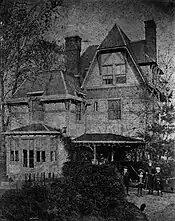

Lindenshade (Horace Howard Furness house), Wallingford, Pennsylvania (c. 1873, demolished 1940). A country house built for the architect's brother, it was later greatly expanded. Thomas Hockley house, 235 S. 21st St., Philadelphia (1875), Furness & Hewitt.

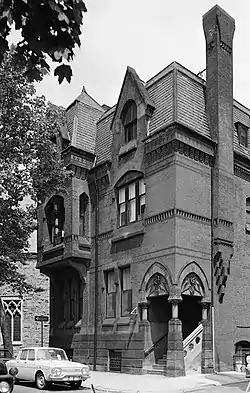

Thomas Hockley house, 235 S. 21st St., Philadelphia (1875), Furness & Hewitt. Gatehouses, Philadelphia Zoo, Fairmount Park, Philadelphia (1875–76, altered), Furness & Hewitt.

Gatehouses, Philadelphia Zoo, Fairmount Park, Philadelphia (1875–76, altered), Furness & Hewitt. Centennial National Bank, Philadelphia (1876), now Paul Peck Alumni Center, Drexel University.

Centennial National Bank, Philadelphia (1876), now Paul Peck Alumni Center, Drexel University. Brazilian Section, Main Exhibition Building, Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia (1876).

Brazilian Section, Main Exhibition Building, Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia (1876). J. F. Fryer cottage, Cape May, New Jersey (1878–79). The pierced-tile inserts in the railings are believed to have come from the Japanese Pavilion at the 1876 Centennial Exposition.

J. F. Fryer cottage, Cape May, New Jersey (1878–79). The pierced-tile inserts in the railings are believed to have come from the Japanese Pavilion at the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Knowlton (William H. Rhawn mansion), Northeast Philadelphia (1881).

Knowlton (William H. Rhawn mansion), Northeast Philadelphia (1881). Dolobran (Clement A. Griscom mansion), Haverford, Pennsylvania (1881, circa 1888, 1894).

Dolobran (Clement A. Griscom mansion), Haverford, Pennsylvania (1881, circa 1888, 1894). Reliance Insurance Company of Philadelphia (1881–82, demolished 1960).

Reliance Insurance Company of Philadelphia (1881–82, demolished 1960).

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station, Philadelphia (1886–88, demolished 1963), looking west from 24th Street.

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station, Philadelphia (1886–88, demolished 1963), looking west from 24th Street. Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station, Philadelphia (1886–88, demolished 1963), stairs from Lower Waiting Room.

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station, Philadelphia (1886–88, demolished 1963), stairs from Lower Waiting Room. Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station, Pittsburgh (1887, demolished 1955).

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station, Pittsburgh (1887, demolished 1955). Idlewild, Media, Pennsylvania (1888). Furness's own country house is reminiscent of his University of Pennsylvania Library.

Idlewild, Media, Pennsylvania (1888). Furness's own country house is reminiscent of his University of Pennsylvania Library. Alexander J. Cassatt townhouse, 202 West Rittenhouse Square, Philadelphia (altered by Furness c. 1888, demolished 1972).

Alexander J. Cassatt townhouse, 202 West Rittenhouse Square, Philadelphia (altered by Furness c. 1888, demolished 1972). Horace Jayne House, 19th & Delancey Sts., Philadelphia (1895). The grandest of his surviving city houses, Mrs. Jayne was Furness's niece Caroline.

Horace Jayne House, 19th & Delancey Sts., Philadelphia (1895). The grandest of his surviving city houses, Mrs. Jayne was Furness's niece Caroline. Merion Cricket Club, Haverford, Pennsylvania (1896–97). Allen Evans was a founding member of the club, and probably designed all its buildings.

Merion Cricket Club, Haverford, Pennsylvania (1896–97). Allen Evans was a founding member of the club, and probably designed all its buildings. Arcade Building and pedestrian bridge to Broad Street Station, Philadelphia (1901–02, demolished 1969).

Arcade Building and pedestrian bridge to Broad Street Station, Philadelphia (1901–02, demolished 1969). Girard Trust Company Building, Philadelphia (1907), (now The Ritz-Carlton Philadelphia). The concept for the bank was Furness's, but it was designed by Allen Evans and the New York firm of McKim, Mead and White.

Girard Trust Company Building, Philadelphia (1907), (now The Ritz-Carlton Philadelphia). The concept for the bank was Furness's, but it was designed by Allen Evans and the New York firm of McKim, Mead and White. Williamson Free School of Mechanical Trades campus (1890), (Rowan Hall shown) Middletown Township, Pennsylvania.

Williamson Free School of Mechanical Trades campus (1890), (Rowan Hall shown) Middletown Township, Pennsylvania. Graver's Lane Station, Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, Philadelphia (1882).

Graver's Lane Station, Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, Philadelphia (1882).

See also

Notes

- ↑ Frank Furness was a curious character. He affected the English in fashion. He wore loud plaids, and a scowl, and from his face depended fan-like a marvelous red beard, beautiful in tone with each separate hair delicately crinkled from beginning to end. Moreover, his face was snarled and homely as an English bulldog's. Louis's eyes were riveted, in infatuation, to this beard, as he listened to a string of oaths a yard long. For it seemed that after he had delivered his initial fiat [of asking for a job], Furness looked at him half blankly, half enraged, as at another kind of dog that had slipped in through the door. His first question had been to Louis's experience, to which Louis replied, modestly enough, that he had just come from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston. This answer was the detonator that set off the mine which blew up in fragments all schools in the land and scattered the professors headless and limbless to the four quarters of earth and hell. Louis, he said, was a fool. He said Louis was an idiot to have wasted his time in a place where one was filled with sawdust, like a doll, and became a prig, a snob, and an ass. As the smoke blew away, he said: "Of course you don't know anything and are full of damnable conceit." Louis agreed to the ignorance; demurred as to conceit; and added that he belonged to that rare class who were capable of learning, and desired to learn. This answer mollified the dog-man, and he seemed intrigued that Louis stared at him so pertinaciously. "Of course, you don't want any pay," he said. To which Louis replied that ten dollars a week would be a necessary honorarium. "All right," said he of the glorious beard, with something scraggy on his face, that might have been a smile. "Come tomorrow morning for a trial, but I prophesy you won't outlast a week." So Louis came. At the end of that week Furness said, "You may stay another week," and at the end of that week Furness said, "You may stay as long as you like." Furness "made buildings out of his head." ... And Furness as a freehand draftsman was extraordinary. He had Louis hypnotized, especially when he drew and swore at the same time.[2] — Louis Sullivan, The Autobiography of an Idea (1922).

References

- ↑ "Philadelphia to Get Its Tallest Apartment Building - NYTimes.com". web.archive.org. March 4, 2016.

- ↑ Louis Sullivan, The Autobiography of an Idea (New York: Press of the American Institute of Architects, 1922), pp. 191-93.

- ↑ James F. O'Gorman, George E. Thomas & Hyman Myers, The Architecture of Frank Furness (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973), pp. 200-03.

- 1 2 3 Michael J. Lewis, Frank Furness: Architecture and the Violent Mind (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc., 2001).

- ↑ Quoted in David Hanks, "Daniel Pabst," Nineteenth Century Furniture: Innovation, Revival, and Reform (New York: Art & Antiques, 1982), p. 43.

- ↑ Roosevelt dining table Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, from High Museum of Art.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Thomas, George E.; et al. (1996). Frank Furness: The Complete Works, Revised Edition. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 218, 224, 334, 336. ISBN 1-56898-094-9.

- ↑ PAFA armchair, from Victoria and Albert Museum.

- ↑ "Frank Furness - Recipient". The Hall of Valor Project. Sightline Media Group. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ↑ Wittenberg, 2000.

- ↑ "Laurel Hill Cemetery (1836)". www.associationforpublicart.org. Association for Public Art. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ↑ Lewis Mumford, The Brown Decades: A Study of Arts in America 1865-1895 (New York: 1931), p. 144.

- ↑ Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1958, revised 1963), pp. 194-95.

- ↑ Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (New York: Museum of Modern Art Papers on Architecture, 1966), pp. 56-57.

- ↑ Louis I. Kahn was saluted as the Chapter's great architect of the present. AIA 100: Centennial Yearbook (Philadelphia Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, 1970), pp. 12-13.

- ↑ Modern Gothic desk, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- ↑ Modern Gothic chair, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- ↑ Furness-Pabst bookcase Archived December 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, from University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Roosevelt dining table Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, from High Museum of Art.

- ↑ Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts armchair, from Victoria and Albert Museum.

- ↑ Furness schedule of events

- ↑ Furness Residence Hall

- ↑ Northern Savings Fund Society Building at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- ↑ Philadelphia Zoo Gatehouses at Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

- ↑ Kensington National Bank at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- ↑ "Frank Furness (1839-1912)". Philadelphia Buildings. Archived from the original on January 26, 2002.

- ↑ Undine Barge Club Archived June 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Horace Jayne house from Flickr

- ↑ The concept for this building was Furness's, but it was designed by his partner, Allen Evans, along with the New York firm of McKim, Mead and White. George E. Thomas, Jeffrey A. Cohen & Michael J. Lewis, Frank Furness: The Complete Works (Princeton Architectural Press, revised edition 1996), pp. 338-39.

- ↑ Girard Trust Company at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- ↑ Winters, Kevin (January 1, 1900). "Henry Pratt McKean". horshamhistory.org. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ↑ Unitarian Society of Germantown Archived December 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Rodef Shalom Archived March 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine at National Museum of American Jewish History.

- ↑ Lutheran Church of the Holy Communion at Bryn Mawr College.

- ↑ Guarantee Trust Company at Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

- ↑ Seamen's Church of the Redeemer at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- ↑ Provident Life & Trust Co. at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- ↑ Library Company of Philadelphia at Bryn Mawr College.

- ↑ Reliance Insurance Company Building at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- ↑ National Bank of the Republic at Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

- ↑ Baltimore and Ohio Terminal at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- ↑ Broad Street Station at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- ↑ Arcade Building at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- ↑ B&O Water Street Station at Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

- ↑ Pennsylvania Building at Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

- ↑ Wilmington Station at Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

- ↑ Lindenshade at the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- ↑ Lindenshade after 1885 at Bryn Mawr College.

- ↑ Jean and David W. Wallace Hall at the Historic Campus Architecture Project

- ↑ Fryer's Cottage at the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- ↑ Emlen Physick Estate at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- ↑ Dolobran at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- ↑ History from Inn at Ragged Edge.

- ↑ Williamson Free School Main Building Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The Baldwin School at Bryn Mawr College.

- ↑ Recitation Hall from Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

- ↑ Haverford School Archived June 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine from Township of Lower Merion

- ↑ All Hallows Church Archived May 31, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Church of Our Father Archived December 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ St. Michael's interior Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine at Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania

- ↑ New Castle Library

- ↑ 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry Monument from Flickr

- ↑ Merion Cricket Club at the Historic American Buildings Survey.

Sources

- Lewis, Michael J., Frank Furness: Architecture and the Violent Mind, 2001.

- O'Gorman, James F., et al., The Architecture of Frank Furness. Philadelphia Museum of Art; 1973.

- Thayer, Preston, The Railroad Designs of Frank Furness: Architecture and Corporate Imagery in the Late Nineteenth Century, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (Ph.D. dissertation), 1993.

- Thomas, George E., Jeffrey A. Cohen & Michael J. Lewis, Frank Furness: The Complete Works. Princeton Architectural Press, revised edition 1996.

- Venturi, Robert, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. The Museum of Modern Art; 1966.

- Eric J. Wittenberg (2000). "Captain Frank Furness: Brilliant Architect and Medal of Honor winner". The Sixth Pennsylvania Cavalry, "Rush's Lancers". Archived from the original on May 2, 2007. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

Further reading

- History Making Productions. "Frank Furness: A Philadelphia Original". Philadelphia: The Great Experiment. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- Lewis, Michael J. (November 7, 2012). "Building Power". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- Lewis, Michael J. (November 14, 2009). "This Library Speaks Volumes". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

External links

- Project List - Furness, Evans & Co. at Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

- Project List - Frank Furness at Philadelphia Architects and Buildings