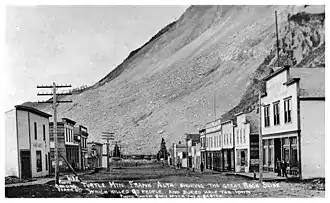

The town of Frank and Turtle Mountain on April 30, 1903, one day after the slide | |

| Date | April 29, 1903 |

|---|---|

| Time | 4:10 a.m. MST |

| Location | Frank, District of Alberta, North-West Territories (now the province of Alberta), Canada |

| Coordinates | 49°35′28″N 114°23′43″W / 49.59111°N 114.39528°W |

| Deaths | 70–more than 90 |

| Website | Frank Slide Interpretive Centre |

The Frank Slide was a massive rockslide that buried part of the mining town of Frank in the District of Alberta of the North-West Territories,[nb 1] Canada, at 4:10 a.m. on April 29, 1903. Around 44 million cubic metres/110 million tonnes (120 million short tons) of limestone rock slid down Turtle Mountain.[1] Witnesses reported that within 100 seconds the rock reached up the opposing hills, obliterating the eastern edge of Frank, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) line and the coal mine. It was one of the largest landslides in Canadian history and remains the deadliest, as between 70 and 90 of the town's residents died, most of whom remain buried in the rubble. Multiple factors led to the slide: Turtle Mountain's formation left it in a constant state of instability. Coal mining operations may have weakened the mountain's internal structure, as did a wet winter and cold snap on the night of the disaster.

The railway was repaired within three weeks and the mine was quickly reopened. The section of town closest to the mountain was relocated in 1911 amid fears that another slide was possible. The town's population nearly doubled its pre-slide population by 1906, but dwindled after the mine closed permanently in 1917. The community is now part of the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass in the Province of Alberta and has a population around 200. The site of the disaster, which remains nearly unchanged since the slide, is now a popular tourist destination. It has been designated a provincial historic site of Alberta and is home to an interpretive centre that receives over 100,000 visitors annually.

Background

The town of Frank was founded in the southwestern corner of the District of Alberta, a subdivision of the North-West Territories, in 1901. A location was chosen near the base of Turtle Mountain in the Crowsnest Pass, where coal had been discovered one year earlier.[2] It was named after Henry Frank who, along with Samuel Gebo, owned the Canadian-American Coal and Coke Company, which operated the mine that the town was created to support.[3] The pair celebrated the founding of the town on September 10, 1901, with a gala opening that featured speeches from territorial leaders, sporting events, a dinner and tours of the mine and planned layout for the community. The CPR ran special trains that brought over 1,400 people from neighbouring communities to celebrate the event.[3] By April 1903, the permanent population had reached 600, and the town featured a two-storey school and four hotels.[4]

Turtle Mountain stands immediately south of Frank. It consists of an older limestone layer folded over on top of softer materials such as shale and sandstone. Erosion had left the mountain with a steep overhang of its limestone layer.[5] It has long been unstable; the Blackfoot and Kutenai peoples called it "the mountain that moves" and refused to camp in its vicinity.[6] In the weeks leading up to the disaster, miners occasionally felt rumblings from within the mountain, while the pressure created by the shifting rock sometimes caused the timbers supporting the mine shafts to crack and splinter.[7]

Rockslide

In the early morning hours of April 29, 1903, a freight train pulled out of the mine and was slowly making its way towards the townsite when the crew heard a deafening rumble behind them. The engineer immediately set the throttle to full speed ahead and sped his train to safety across the bridge over the Crowsnest River.[8] At 4:10 am, 30 million cubic metres of limestone rock with a mass of 110 million tonnes (121 million US tons) broke off the peak of Turtle Mountain. The section that broke was 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) wide, 425 metres (1,394 ft) high and 150 metres (490 ft) deep.[1] Witnesses to the disaster claimed it took about 100 seconds for the slide to reach up the opposing hills, indicating the mass of rock travelled at a speed of about 112 kilometres per hour (70 mph).[9] The sound was heard as far away as Cochrane, over 200 kilometres (120 mi) north of Frank.[5]

Initial reports on the disaster indicated that Frank had been "nearly wiped out" by the mountain's collapse. It was thought the rockslide was triggered by an earthquake, volcanic eruption or explosion within the mine.[10] The majority of the town survived, but the slide buried buildings on the eastern outskirts of Frank. Seven cottages were destroyed, as were several businesses, the cemetery, a 2-kilometre (1.2 mi) stretch of road and railroad tracks, and all of the mine's buildings.[11]

Approximately 100 people lived in the path of destruction, located between the CPR tracks and the river.[12] The death toll is uncertain; estimates range between 70[11] and 90. It is the deadliest landslide in Canadian history[9] and was the largest until the Hope Slide in 1965.[13] It is possible that the toll may have been higher, since as many as 50 transients had been camped at the base of the mountain while looking for work. Some residents believed that they had left Frank shortly before the slide, though there is no way to be certain.[7] Most of the victims remain entombed beneath the rocks; only 12 bodies were recovered in the immediate aftermath.[11] The skeletons of six additional victims were unearthed in 1924 by crews building a new road through the slide.[14]

Initial news reports stated that between 50 and 60 men were within the mountain and had been buried with no hope of survival.[10] In reality, there were 20 miners working the night shift at the time of the disaster. Three had been outside the mine and were killed by the slide.[15] The remaining 17 were underground. They discovered that the entrance was blocked and water from the river, which had been dammed by the slide, was coming in via a secondary tunnel.[16] They unsuccessfully tried to dig their way through the blocked entrance before one miner suggested he knew of a seam of coal that reached the surface. Working a narrow tunnel in pairs and threes, they dug through the coal for hours as the air around them became increasingly toxic.[17] Only three men still had enough energy to continue digging when they broke through to the surface late in the afternoon.[16] The opening was too dangerous to escape from due to falling rocks from above. Encouraged by their success, the miners cut a new shaft that broke through under an outcropping of rock that protected them from falling debris. Thirteen hours after they were buried, all 17 men emerged from the mountain.[17]

The miners found that the row of cottages that served as their homes had been devastated and some of their families killed, seemingly at random.[7] One found his family alive and safe in a makeshift hospital, but another emerged to discover his wife and four children had died.[18] Fifteen-year-old Lillian Clark, working a late shift that night in the town's boarding house, had been given permission to stay overnight for the first time.[12] She was the only member of her family to survive. Her father was working outside the mine when the slide hit, while her mother and six siblings were buried in their home.[11] All 12 men living at the CPR work camp were killed, but 128 more who were scheduled to move into the camp the day before the slide had not arrived—the train that was supposed to take them there from Morrissey, British Columbia, failed to pick them up.[19] The Spokane Flyer, a passenger train heading west from Lethbridge, was saved by CPR brakeman Sid Choquette, one of two men who rushed across the rock-strewn ground to warn the train that the track had been buried under the slide.[20] Through falling rocks and a dust cloud that impaired his visibility, Choquette ran for 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) to warn the oncoming locomotive of the danger. The CPR gave him a letter of commendation and a $25 cheque (approximately $750 in 2019) in recognition of his heroism.[7]

Aftermath

Early on April 30 a special train from Fort Macleod arrived with police officers and doctors.[21] Premier Frederick Haultain arrived at the disaster site on May 1, where he met with engineers who had investigated the top of Turtle Mountain. Though new fissures had formed at the peak, they felt there was limited further risk to the town; nevertheless, the CPR's chief engineer felt that Frank was in imminent danger from another slide. Siding with the latter, Haultain ordered the town evacuated,[22] and the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) sent two of its top geologists to investigate further. They reported that the slide had created two new peaks on the mountain and that the north peak, overlooking the town, was not in imminent danger of collapse.[23] As a result, the evacuation order was lifted on May 10 and Frank's citizens returned.[24] The North-West Mounted Police, reinforced by officers who arrived from Cranbrook, Fort Macleod and Calgary, kept tight control of the town and ensured that no cases of looting occurred during the evacuation.[25]

Clearing the CPR line was of paramount importance.[26] Approximately 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) of the main line had been buried under the slide, along with part of an auxiliary line.[5] The CPR had the line cleared and rebuilt within three weeks.[11] Intent on reopening the mine, workers opened passageways to the old mine works by May 30. To their amazement, they discovered that Charlie the horse, one of three who worked in the mine, had survived for over a month underground.[27] The mule had subsisted by eating the bark off the timber supports and by drinking from pools of water. The mule died when his rescuers overfed him on oats and brandy.[28]

The town's population not only recovered but grew; the 1906 census of the Canadian Prairies listed the population at 1,178.[29] A new study commissioned by the Dominion government determined that the cracks in the mountain continued to grow and that the risk of another slide remained. Consequently, parts of Frank closest to the mountain were dismantled or relocated to safer areas.

Causes

Several factors led to the Frank Slide.[30] A study conducted by the GSC immediately following the slide concluded that the primary cause was the mountain's unstable anticline formation; a layer of limestone rested on top of softer materials that, after years of erosion, resulted in a top-heavy, steep cliff.[31] Cracks laced the eastern face of the mountain while underground fissures allowed water to flow into the mountain's core.[32] Local Indigenous peoples of the area, the Blackfoot and Ktunaxa, had oral traditions referring to the peak as "the mountain that moves".[32] Miners noticed the mountain had become increasingly unstable in the months preceding the slide; they felt small tremors and the superintendent reported a "general squeeze" in the mountain at depths between 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) and 1,500 metres (4,900 ft). They found that coal broke from its seam; it was said to have practically mined itself.[33]

An unusually warm winter, with warm days and cold nights, was also a factor. Water in the mountain's fissures froze and thawed repeatedly, further weakening the mountain's supports.[8] Heavy snowfall in the region in March was followed by a warm April, causing the mountain snows to melt into the fissures.[7] GSC geologists concluded that the weather conditions that night likely triggered the slide. The crew of the freight train that arrived at Frank shortly before the disaster said it was the coldest night of the winter, with overnight temperatures falling below −18 °C (0 °F). Geologists speculated that the cold snap and rapid freezing resulted in expansion of the fissures, causing the limestone to break off and tumble down the mountain.[33]

Though the GSC concluded that mining activities contributed to the slide, the facility's owners disagreed. Their engineers claimed that the mine bore no responsibility.[34] Later studies suggested that the mountain had been at a point of "equilibrium"; even a small deformation such as that caused by the mine's existence would have helped trigger a slide.[35] The mine was quickly re-opened, even though rock continued to tumble down the mountain.[36] Coal production at Frank peaked in 1910,[37] but the mine was permanently closed in 1917 after it became unprofitable.[36]

The slide created two new peaks on the mountain; the south peak stands 2,200 metres (7,200 ft) high and the north peak 2,100 metres (6,900 ft).[1] Geologists believe that another slide is inevitable, though not imminent. The south peak is considered the most likely to fall; it would likely create a slide about one-sixth the size of the 1903 slide.[38] The mountain, continuously monitored for changes in stability, has been studied on numerous occasions.[39] The Alberta Geological Survey operates a state-of-the-art monitoring system used by researchers around the world.[40] Over 80 monitoring stations have been placed on the face of the mountain to provide an early warning system for area residents in case of another slide.[41]

Geologists have debated about what caused the slide debris to travel the distance it did. The "air cushion" theory, an early hypothesis, postulated that a layer of air was trapped between the mass of rock and the mountain, which caused the rock to move a greater distance than would otherwise be expected.[42] "Acoustic fluidization" is another theory, which suggests that large masses of material create seismic energy that reduces friction and causes the debris to flow down the mountain as though it is a fluid.[43] Geologists created the term "debris avalanche" to describe the Frank Slide.[9]

Legends

Numerous legends and misconceptions were spawned in the aftermath of the slide.[36] The entire town of Frank was claimed to have been buried, though much of the town itself was unscathed.[44] The belief that a branch of the Union Bank of Canada had been buried with as much as $500,000 persisted for many years.[45] The bank—untouched by the slide—remained in the same location until it was demolished in 1911, after which the buried treasure legend arose.[46] Crews building a new road through the pass in 1924 operated under police guard as it was believed they could unearth the supposedly buried bank.[14]

Several people, telling amazing stories to those who would listen, passed themselves off as the "sole survivor" in the years following the slide.[36] The most common such tale is that of an infant girl said to have been the only survivor of the slide. Her real name unknown, the girl was called "Frankie Slide". Several stories were told of her miraculous escape: she was found in a bale of hay, lying on rocks, under the collapsed roof of her house or in the arms of her dead mother.[47] The legend was based primarily on the story of Marion Leitch, who was thrown from her home into a pile of hay when the slide enveloped her home. Her sisters also survived; they were found unharmed under a collapsed ceiling joist. Her parents and four brothers died.[7] Influencing the story was the survival of two-year-old Gladys Ennis, who was found outside her home in the mud. The last survivor of the slide, she died in 1995.[11] In total, 23 people in the path of the slide survived, in addition to the 17 miners who escaped from the tunnels under Turtle Mountain.[46] A ballad by Ed McCurdy featuring the story of Frankie Slide was popular in parts of Canada in the 1950s.[48] The slide has formed the basis of other songs, including "How the Mountain Came Down" by Stompin' Tom Connors ,[49] and more recently, "Frank, AB" by The Rural Alberta Advantage.[50] The Frank Slide has been the subject of several books, both historical[51] and fictional.[52]

Legacy

Curious sightseers flocked to the site of the slide within the day of the disaster.[24] It has remained a popular tourist destination, in part due to its proximity to the Crowsnest Highway (Highway 3). The province built a roadside turnout in 1941 to accommodate the traffic.[53] Town boosters unsuccessfully sought to have the site designated as a National Historic Site in 1958. It was later designated a Provincial Historic Site of Alberta.[54] The provincial government designated the slide area a restricted development zone in 1976, which prevents alteration of the site.[55] In 1978, a memorial plaque was erected.[56] The Frank Slide Interpretive Centre, within sight of the mountain, was opened in 1985. A museum and tourist stop document the Frank Slide and the region's coal mining history.[57]

Though Frank recovered from the slide and achieved a peak population of 1,000 shortly thereafter, the closure of the mine resulted in a longstanding decline in population.[37] Frank ceased to be an independent community in 1979, when it was amalgamated into the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass along with the neighbouring communities of Blairmore, Coleman, Hillcrest, and Bellevue.[58] Frank is now home to about 200 residents.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ The province of Alberta was not created until September 1905, more than two years after the slide. The community was still part of the North-West Territories when the incident occurred.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Frank Slide facts (PDF), Government of Alberta, retrieved April 29, 2019

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 55

- 1 2 Anderson 2005, p. 6

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 57

- 1 2 3 Frequently Asked Questions about the Frank Slide, Government of Alberta, retrieved May 27, 2012

- ↑ Bonikowsky, Laura, Frank Slide, Historica-Dominion Institute of Canada, archived from the original on April 5, 2012, retrieved April 30, 2012

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bergman, Brian (April 28, 2003), "100th anniversary of Frank Slide disaster", Maclean's Magazine, Historica-Dominion Institute of Canada, archived from the original on April 4, 2012, retrieved May 1, 2012

- 1 2 van Herk 2001, p. 385

- 1 2 3 Landslides, Natural Resources Canada, retrieved June 2, 2012

- 1 2 "A disaster", Montreal Gazette, p. 1, April 30, 1903, retrieved May 1, 2012

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 1930: 90 seconds of terror in the Frank rockslide, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, retrieved May 21, 2016

- 1 2 Anderson 2005, p. 63

- ↑ Kerr 1990, p. 27

- 1 2 "Skeletons at Blairmore", Montreal Gazette, p. 1, May 17, 1924, retrieved May 23, 2012

- ↑ Kerr 1990, p. 12

- 1 2 Kerr 1990, p. 15

- 1 2 Anderson 2005, p. 86

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 88

- ↑ Kerr 1990, p. 24

- ↑ Anderson 2005, pp. 71–72

- ↑ Anderson, Frank W (1968). The Frank Slide Story. Calgary: Frontiers Unlimited. p. 47.

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 91

- ↑ Kerr 1990, p. 33

- 1 2 Anderson 2005, p. 93

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 92

- ↑ Kerr 1990, p. 30

- ↑ Anderson 2005, p. 94

- ↑ Clarke, Jay (September 29, 1989), "Scene of rock slide still startling", Spokane Chronicle, p. 14, retrieved May 7, 2012

- ↑ Recensement des Provinces du Nord-Ouest, 1906 (in French), Government of Canada (via University of Alberta Libraries), 1906, p. 101, retrieved June 15, 2012

- ↑ Benko & Stead 1998, p. 302

- ↑ Kerr 1990, p. 41

- 1 2 The Frank Slide story, Government of Alberta, retrieved May 20, 2012

- 1 2 Anderson 2005, p. 96

- ↑ Kerr 1990, p. 38

- ↑ Benko & Stead 1998, p. 311

- 1 2 3 4 Byfield 1992, p. 377

- 1 2 Kerr 1990, p. 36

- ↑ Kerr 1990, p. 47

- ↑ Benko & Stead 1998, p. 300

- ↑ Gignac, Tamara (January 8, 2010), "High-tech radar guards residents against disaster" (PDF), Calgary Herald, Alberta Geological Survey, retrieved May 21, 2012

- ↑ Seskus, Tony (April 6, 2008), "Site of historic landslide shifting" (PDF), Calgary Herald, Alberta Geological Survey, retrieved May 21, 2012

- ↑ Kerr 1990, p. 40

- ↑ Corbett, Bill (March 2004), "North America's deadliest landslide still poses questions—100 years later", The Pegg, Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of Alberta, archived from the original on January 15, 2013, retrieved May 27, 2012

- ↑ Kerr 1990, p. 9

- ↑ "Every spring Turtle Mountain sends grim reminders of past", Regina Leader-Post, p. 64, May 7, 1980, retrieved May 14, 2012

- 1 2 Anderson 2005, p. 99

- ↑ Kerr 1990, p. 21

- ↑ Liddell, Ken (December 21, 1950), "Frank recalls slide but without a song", Calgary Herald, p. 8, retrieved May 30, 2012

- ↑ Disaster songs, Historica-Dominion Institute of Canada, retrieved May 30, 2012

- ↑ Kinos-Goodin, Jesse (April 27, 2011), "The Rural Alberta Advantage take a breath", National Post, archived from the original on July 8, 2012, retrieved May 30, 2012

- ↑ Books and links, Library and Archives Canada, retrieved May 30, 2012

- ↑ Erion, Chuck (August 4, 2007), "Two books to get over feeling Harry-ed", Guelph Mercury, p. C5, retrieved May 30, 2012

- ↑ "Frank Slide tourist site", Calgary Herald, p. 2, September 12, 1941, retrieved May 23, 2012

- ↑ Shiels, Bob (January 31, 1980), "The Kerrs want a museum in the Pass", Calgary Herald, p. D14, retrieved May 23, 2012

- ↑ "Rock bottom bargain", Calgary Herald, p. A1, September 11, 1984, retrieved May 23, 2012

- ↑ Crowsnest Pass Historical Society (1979). Crowsnest and its people. Coleman: Crowsnest Pass Historical Society. p. xi. ISBN 0-88925-046-4.

- ↑ Shiels, Bob (May 1, 1985), "Guests hail Frank Slide centre", Calgary Herald, p. F10, retrieved May 23, 2012

- ↑ White, Geoff (October 19, 1978), "Legislation introduced to unify Crowsnest area", Calgary Herald, p. A3, retrieved May 23, 2012

Sources

- Anderson, Frank W. (2005) [1968], Wilson, Diana (ed.), Triumph and Tragedy in the Crowsnest Pass, Surrey, British Columbia: Heritage House, ISBN 1-894384-16-4

- Benko, Boris; Stead, Doug (1998). "The Frank slide: a reexamination of the failure mechanism" (PDF). Canadian Geotechnical Journal. 35 (2): 299–311. doi:10.1139/t98-005.

- Byfield, Ted, ed. (1992), Alberta in the 20th Century: The Birth of the Province, 1900–1910, vol. 2, Edmonton, Alberta: United Western Communications, ISBN 0-9695718-1-X

- Kerr, J. William (1990), Frank Slide, Calgary, Alberta: Barker, ISBN 0-9694761-0-8

- van Herk, Aritha (2001), Mavericks: An Incorrigible History of Alberta, Toronto, Ontario: Penguin Group, ISBN 0-14-028602-0

External links

- Turtle Mountain Monitoring Project

- "The 425m Landslide that Engulfed an Albertan Town" (2010)

- SOS! Canadian Disasters, a virtual museum exhibition at Library and Archives Canada

- Read, R.S.; et al. "Frank Slide a Century Later: The Turtle Mountain Monitoring Project" (PDF). Michigan Tech.