Frederic James Shields (14 March 1833 – 26 February 1911) was a British artist, illustrator, and designer closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelites through Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown.

Early years

Frederic James Shields was born in Hartlepool on 14 March 1833, the eldest of four children of Georgiana Storey (d. 1853) a straw hat maker and John Shields (c.1808–1849) a bookbinder, stationer, and printer who ran a circulating library. Baptised Frederick, he later adopted the spelling Frederic.[1]

The family moved to London in 1839 and Shields attended St Clement Danes parish school until he was fourteen. His father was a skilled draughtsman and gave Shields his first drawing lessons, and the boy went on to study engraving at evening classes at the London Mechanics' Institute, winning a drawing prize aged thirteen. In October 1847, he was apprenticed to a firm of lithographers. His father's business failed in 1848, and the family moved back north where Shields joined them.[1]

He was brought up in extreme poverty, and as a young man was employed on hack-work for commercial engravers. He managed to study art briefly at evening classes in London and then in Manchester, where he settled in about 1848. He spent much of his artistic life in Manchester, and it was there that his drawings and watercolours were noticed and appreciated.

Book illustrations

The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857 made a great impression on Shields. His style became more elegant and minute. Inspired by Edward Moxon's illustrated edition of Poems by Alfred Tennyson (1857), he started to work in black-and-white as a book illustrator. His designs for Daniel Defoe's History of the Plague (1862) and John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress (1864) were very successful and brought him admirers, among whose were John Ruskin and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. In May 1864 Shields went to London and met Rossetti, through whom he soon came to know the whole Pre-Raphaelite circle.

Influenced by Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown, Shields was sensitive to the artistic legacy of William Blake who was admired by the Pre-Raphaelites. His portrayal of the room in which William Blake had died (Manchester Art Gallery, a version at Delaware Fine Art Museum, USA) inspired a poem by DG Rossetti.[2]

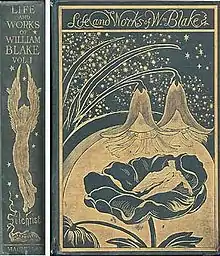

Frederic Shields was deeply religious man. His faith influenced his artistic manner which was gradually becoming more mannered and mystical in theme. These changes can be seen in his most significant book design – the second edition of Alexander Gilchrist's Life of William Blake (London: Macmillan, 1880. 2 vols). It was inspired by Rossetti about whom The New York Times wrote:

Rossetti shows increasing zeal in /…/ recommending others who would be qualified to help with the work. Of Frederic Shields he says, 'Of course his labour would be purely one of love. He is an ardent worshipper of Blake, and no man could write better about him or with more practical exactness.'[3]

Shields' binding can be considered today as a very fine example of early Art Nouveau style.

In London

In 1865, he was elected an associate of the Royal Watercolour Society, but it was not until 1876, after a visit to Italy, that he finally settled in London.

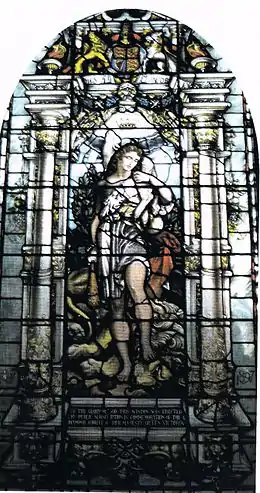

His relations with the Rossetti family remained very close. He was in constant correspondence with Christina Rossetti, and in 1883, after the death of DG Rossetti, his mother commissioned from Shields "two lights in stained glass, to be placed in the little window which overlooks the grave of Dante Gabriel Rossetti in the churchyard at Birchington, near Margate."[4]'

The first light (left side) is Rossetti's own design adapted by Shields from The Passover in the Holy Family: Gathering Bitter Herbs (watercolour, 1855–56, Tate Gallery). The second light is designed by Shields and portrays Christ leading the Blind Man Out of Bethsaida. The inscription under the window reads: “To the glory of God and in memory of my Son Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti. Born in London 12 May 1828. Died at Birchington Easter Day 1882.”

An extract from Rossetti's brother's diary states a man from D Brucciani & Co, London was commissioned to take a cast of Gabriel's face. This proved extremely disappointing. So the family requested Shields make a drawing of him, which he duly did. Shields recorded in his diary "Made two copies (in misery) of the drawing of Rossetti's face for Christina and Watts.”

Shields also became a very close friend with the artist Emily Gertrude Thomson. He shared a stained glass commission with her named The Britomart Window at the Cheltenham Ladies' College based upon six pictures taken from Spenser's allegory The Faerie Queene. Emily produced a portrait of Frederic Shields (shown above) and when he finally retired to Merton in Surrey she frequently visited him.

Shields made numerous chalk drawings. In 1864 he had begun to experiment with a certain French "compressed charcoal". He showed this medium to Rossetti who at once adopted this material alone for all his larger studies.

Shields also undertook designing of three-dimensional objects of applied art. Several artefacts, designed, painted and signed by Shields are known.

Shields however strived for large-scale projects of spiritual content. This might have been the reason that in 1879, when the murals on the history of Manchester for Manchester Town Hall were commissioned from both Ford Madox Brown and Frederic Shields, he withdrew, leaving Brown to complete all twelve works. Madox Brown did however immortalise Shields in one of the Manchester Murals: he made him sit for Wycliffe in the fresco of the Reformer's Trial.

Shields' most important legacy is three successive series of designs for stained glass and mural decorations for the Chapel of Eaton Hall, Cheshire, seat of the Dukes of Westminster (1876–1888); for the private chapel of William Houldsworth in Kilmarnock (1877–1879) and for the St Elisabeth's Church, Reddish, Stockport (1881–1883); and finally for the Chapel of the Ascension, Bayswater Road, London (1888–1910).

Eaton Hall Chapel, Cheshire

Eaton Hall in Cheshire was designed by Alfred Waterhouse and built in 1873–1874 for Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster (1825–1899). From 1876–1888, Shields provided for its chapel designs for stained glass and stone mosaics on the theme 'Te Deum Laudamus'.

This large-scale commission helped him to clarify and formulate his thoughts on Art as applied to the Faith: "Nearly ninety subjects, all told, not isolated, but such as could be linked in blessed continuity – to keep the heart hot, and the mind quick, with its grand purpose – the Praise of God and of his Son Jesus Christ, from the lives of apostles, prophets, martyrs, and the Holy Church of all the ages."[5]

This work firmly established his international reputation. It was praised in Boston magazine The Atlantic Monthly in 1882: "It is in the interpretative function of art that Mr Shields has shown his great power; and the interpretation is not of a school of thought, nor of a historic tradition, nor of an individual fancy, but of a catholic and comprehensive conception of the spiritual life. The domination thought is in the vivifying power of the spirit, and the religious sentiment is unhesitating and profound."[6] In 1884, the New York Times, commenting on Shields' Eaton Hall Chapel designs, wrote: "Mr Shields, who occupies a distinguished position as an artist in England, owes his reputation in part to the notice taken of his early works by Mr J. Ruskin and Rossetti and their judgement of his in his earliest efforts was not mistaken. Mr Shields’s career as an artist, shows, that from making lithographic prints for bedecking bolts of calico, he rose by hard work to be one of the leading painters of religious subjects in England."[7]

The Private Chapel of WH Houldsworth in Kilmarnock and St Elisabeth's Church, Reddish, Stockport

In 1877–1879, Frederic Shields produced designs on the subject "The Triumph of Faith". They were to decorate the private chapel of the industrialist and mill-owner William Houldsworth. Born in Manchester, he eventually made his home in Kilmarnock, Scotland, and it was there that Shields' designs meant to be. The design drawings were accomplished in 1878–1879. Alexander McLaren who saw them in April 1879, wrote: "Wealth of reverent thought and profound suggestiveness /.../ in power and harmony, in weighty meaning expressed in fair shape, in delightful and not too misty symbolism they seem to me to surpass all that you have done, so far as I know it. /.../ I only wish they were not going to be buried in a hole in Ayrshire."[8]

The idea of using of Shields' designs at the Kilmarnock chapel was eventually abandoned. The designs were reworked and re-used a few years later, at St Elisabeth's Church, Reddish, Stockport, which was commissioned by WH Houldsworth from Alfred Waterhouse. The church was designed in Neo-Gothic style and built in 1881–1883. In comparison with the Kilmarnock chapel, the decorative scheme was much expanded, and Shields' cartoons provided designs for stained-glass windows.[9]

The cartoons themselves were bought from Frederic Shields by Manchester cotton manufacturer Henry Steinthal Gibbs (1829–1894) and eventually found their way to Manchester Art Gallery.[10]

The Chapel of the Ascension, London

His intense religious feeling was expressed even more strongly in his last large-scale project: the cycle of murals that he painted in 1888–1910 for the Chapel of the Ascension in the Bayswater Road, London. The Chapel was commissioned by Emelia Russell Gurney, the widow of judge and politician, the Recorder of London Russell Gurney (1804–1878). It was envisaged as a little decorated hall inspired by Italian Renaissance architecture and paintings. Young architect Herbert Percy Horne (1864–1916) was to build the chapel, and Frederick Shields to decorate it. The initial idea was however developed and clarified under the strong influence of Shields' religious feelings and artistic views: "It involves great issues, and may lead to a new departure in the alliance or service of Art to Piety. Symbols affect men’s imagination and faith mightily still. The little spot should be pure – so that anything that defileth – if it entered – should feel itself abhorred and reproved silently. I would wish it lit from the roof, shut out from all but heaven’s vault…"[11]

Mrs Russell Gurney suggested that Shields and Horne travel to Northern Italy for close study of examples of Renaissance architecture and decoration. In the autumn 1889, Shields and Horne visited Milan, Pisa, Lucca, Florence, Assisi, Rome, and Orvieto.

As a result, Shields created a complex iconographical programme, in which Biblical subjects were mingled with more allegorical concepts. He wrote to G. F. Watts: "I should have to write a book to lay before you my scheme, but Prophets and Apostles, Christian Virtues and worldly vices, Gospel and Apostolic history, types and symbols all enter into it."[12]

For the Chapel of the Ascension, Shields re-used a number of images of prophets and apostles which had earlier been designed for the Eaton Chapel. But what had been realised at Eaton Chapel in medium of stained glass and stone mosaics (which he did not like), appeared at the Chapel of the Ascension as oil paintings on canvas.

The harmony of decorative art and architecture which had been achieved by Horne and Shields was greatly appreciated by their much younger contemporary Frank Brangwyn. He would later describe Shields' decorations as "irrespective of fashion and the changing of artistic outlook. These decorations are, in every sense, the most complete examples of decoration done in England."[13]

The Chapel of the Ascension was severely damaged during the Second World War and Shields' mosaics and paintings perished. Shields' designs however survived. They were recovered and secured by Frank Brangwyn in the late 1940s and given to several regional museums in England, namely Wolverhampton Art Gallery and William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow.

St Ann's Church, Manchester

Amongst other important commissions, Shields designed the windows in the Chancel of St Ann's Church, Manchester. He drew out a complete scheme for the church's stained glass based upon the theme of a Shepherd.

The east windows behind the altar and the north and south aisles all have this theme, and were the work of Heaton, Butler and Bayne. The north aisle window was installed in commemoration of the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria. After a bomb attack by the IRA on Manchester in 1996 the window was restored in memory of Maria Isabella Blythe (1898–1985).

The inscription below the south aisle window reads – To the Glory of God initiated by lay helpers of this parish, dedicated at the Coronation of King Edward VII (1902)

Personal details

On 15 August 1874 in Manchester, Shields married Matilda Booth (b. 1856), known as Cissy, a young girl who used to be his model. Her family and Shields's friends had been concerned about the relationship between the 18 year old girl and forty one year old man but the marriage was considered surprising.[1] Shields soon left for a trip to Europe and in 1875 left his new young wife at a boarding school in Brighton run by Margaret Alexis Bell and Mary Bradford. He had been a regular visitor to their previous school Winnington Hall with other Pre-Raphaelite artists.[14]

Matilda's little sister Jessie (b. 1870) was adopted by the Shields family soon after their marriage and sent to school for several years. The marriage was not successful. They did not have children and much of the time lived separately, Cissy eventually leaving him in 1891.[1]

Shields died on 26 February 1911 at Morayfield, Kingston Road, Merton, Surrey. He left an annuity to Cissy but the bulk of his fortune to missionary societies. He was buried in Merton Old Church, Merton, London SW19.[1]

Literature

- Ernestine Mills. The Life and Letters of Frederic Shields. 1912.The Life and Letters of Frederic Shields at Internet Archive The artist, writer and suffragette Mills was taught drawing by Shields from her childhood.[15]

- Frederic Shields. The Chapel of the Ascension##. 1907.

- Frederic Shields Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- Susan W. Thomson, Manchester's Victorian Art Scene And Its Unrecognised Artists, Manchester Art Press, Warrington, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9554619-0-3 Chapter 11, Frederic J Shields – 1833–1911, p.p. 120–144.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Shields, Frederic James (1833–1911), artist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36067. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ↑ Letter to Frederick Shields, 21 May 1880

- ↑ The New York Times. 30.11.1919.

- ↑ Athenæum. 22 September 1883. P.181.

- ↑ Mills, Ernestine. Life and Letters of Frederic Shields. 1912. P.226.

- ↑ Scudder, H E. An English Interpreter. The Atlantic Monthly. Vol.L. 1882

- ↑ The New York Times, 4 August 1884.

- ↑ A McLaren to F Shields. 30 April 1879.In: Ernestine Mills. The Life and Letters of Frederic Shields. London, 1912.P.239.

- ↑ Rev. F.Rothwell. The Triumph of Faith, being a Short description of the windows of this church. Reddish. 1909.

- ↑ Gibbs, HS. Autobiography of a Manchester Cotton Manufacturer: or, Thirty Years Experience of Manchester. London: J. Heywood. 1887.

- ↑ Mills, Ernestine. Life and Letters of Frederic Shields.1912. P.294.

- ↑ Mills, Ernestine. Life and Letters of Frederic Shields.1912. P. 306.

- ↑ Belleroche, W. Brangwyn's Pilgrimage. London: Chapman & Hall, 1948. P.122

- ↑ "Bell, Margaret Alexis (1818–1889), schoolmistress". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.109562. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ↑ "Humanist Heritage: Ernestine Mills (1871-1959)". Humanist Heritage. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

External links

- Manchester Art Gallery.

- Wolverhampton Art Gallery.

- Delaware Fine Art Museum, Wilmington, DE, USA

- Hartlepool Art Gallery.

- 30 artworks by or after Frederic Shields at the Art UK site

- Frederic Shields Collection at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas

- Frederic Shields Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.