| Friday the 13th | |

|---|---|

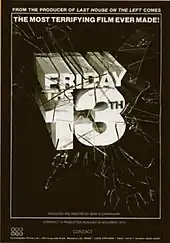

_theatrical_poster.jpg.webp) Theatrical release poster by Alex Ebel | |

| Directed by | Sean S. Cunningham |

| Written by | Victor Miller |

| Produced by | Sean S. Cunningham |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Barry Abrams |

| Edited by | Bill Freda |

| Music by | Harry Manfredini |

Production company | Georgetown Productions Inc.[1] |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $550,000 |

| Box office | $59.8 million[2] |

Friday the 13th is a 1980 American independent slasher film produced and directed by Sean S. Cunningham, written by Victor Miller, and starring Betsy Palmer, Adrienne King, Harry Crosby, Laurie Bartram, Mark Nelson, Jeannine Taylor, Robbi Morgan, and Kevin Bacon. Its plot follows a group of teenage camp counselors who are murdered one by one by an unknown killer while they are attempting to re-open an abandoned summer camp with a tragic past.

Prompted by the success of John Carpenter's Halloween (1978), director Cunningham put out an advertisement to sell the film in Variety in early 1979, while Miller was still drafting the screenplay. After casting the film in New York City, filming took place in New Jersey in the summer of 1979, on an estimated budget of $550,000. A bidding war ensued over the finished film, ending with Paramount Pictures acquiring the film for domestic distribution, while Warner Bros. secured international distribution rights.

Released on May 9, 1980, Friday the 13th was a major box office success, grossing $59.8 million worldwide. Critical response was divided, with some praising the film's cinematography and score, while numerous others derided it for its depiction of graphic violence. Aside from being the first independent film of its kind to secure distribution in the U.S. by a major studio, its box office success led to a long series of sequels, a crossover with the A Nightmare on Elm Street film series, and a 2009 series reboot. A direct sequel, Friday the 13th Part 2, was released one year later.

Plot

In 1958, at Camp Crystal Lake, two counselors sneak inside a cabin to have sex, where an unseen assailant murders them. In present day, camp counselor and cook Annie Phillips is driven halfway to the reopened Camp Crystal Lake by truck driver Enos. Enos warns her about the camp's troubled past, beginning when a young boy drowned in Crystal Lake in 1957. After being dropped off at the halfway point, Annie hitches another ride from an unseen person, who eventually slashes her throat.

At the camp, counselors Ned, Jack, Bill, Marcie, Brenda, and Alice, along with owner Steve Christy, refurbish the cabins. As a thunderstorm approaches, Steve leaves for supplies. Ned sees someone walk into a cabin and follows. While Jack and Marcie have sex, they are unaware of Ned's dead body above them. When Marcie leaves for the bathroom, Jack's throat is pierced with an arrow. The killer kills Marcie next with an axe. Brenda hears a little boy's voice calling for help and ventures outside, where the lights turn on. Brenda screams.

Worried by their friends' disappearances, Alice and Bill investigate. They find the axe in Brenda's bed and the phones disconnected. Steve returns and recognizes the unseen killer who stabs him. When the power goes out, Bill goes to check on the generator. Alice finds his body pinned with arrows to the door. She flees to the main cabin, where Brenda's body is thrown through the window. Mrs. Voorhees, a middle-aged woman who claims to be a friend of Steve, arrives.

She reveals that her son, Jason, was the young boy who drowned in 1957 and she blames his death on neglect by the counselors because they were having sex instead of supervising him. Revealing herself as the killer, she attempts to kill Alice. At the shore, they struggle until Alice is able to decapitate her. Exhausted, Alice falls asleep inside a canoe that floats out on Crystal Lake. When she awakes, Jason's decomposing corpse drags her into the lake, at which point she awakens in a hospital, surrounded by a police sergeant and medical staff. The sergeant says there was no sign of a boy at the lake, to which Alice says, "Then he's still there."

Cast

- Betsy Palmer as Mrs. Pamela Voorhees

- Adrienne King as Alice

- Harry Crosby as Bill

- Jeannine Taylor as Marcie

- Laurie Bartram as Brenda

- Kevin Bacon as Jack

- Mark Nelson as Ned

- Robbi Morgan as Annie

- Peter Brouwer as Steve Christy

- Rex Everhart as Enos, The Truck Driver

- Ronn Carroll as Sgt. Tierney

- Walt Gorney as Crazy Ralph

- Willie Adams as Barry

- Debra S. Hayes as Claudette

- Sally Anne Golden as Sandy

- Ari Lehman as Jason

Production

Development

Friday the 13th was produced and directed by Sean S. Cunningham, who had previously worked with filmmaker Wes Craven on the film The Last House on the Left. Cunningham, inspired by John Carpenter's Halloween,[3] wanted Friday the 13th to be shocking, visually stunning and "[make] you jump out of your seat."[3] Wanting to distance himself from The Last House on the Left, Cunningham wanted Friday the 13th to be more of a "roller-coaster ride."[3]

The original screenplay was tentatively titled A Long Night at Camp Blood.[4] While working on a redraft of the screenplay, Cunningham proposed the title Friday the 13th, after which Miller began redeveloping.[4] Cunningham rushed out to place an advertisement in Variety using the Friday the 13th title.[5] Worried that someone else owned the rights to the title and wanting to avoid potential lawsuits, Cunningham thought it would be best to find out immediately. He commissioned a New York advertising agency to develop his concept of the Friday the 13th logo, which consisted of big block letters bursting through a pane of glass.[6] In the end, Cunningham believed there were "no problems" with the title, but distributor George Mansour stated, "There was a movie before ours called Friday the 13th: The Orphan. It was moderately successful. But someone still threatened to sue. Either Phil Scuderi paid them off, but it was finally resolved."[5]

The screenplay was completed in mid-1979[4] by Victor Miller, who later went on to write for several television soap operas, including Guiding Light, One Life to Live and All My Children; at the time, Miller was living in Stratford, Connecticut, near Cunningham, and the two had begun collaborating on potential film projects.[5] Miller delighted in inventing a serial killer who turned out to be somebody's mother, a murderer whose only motivation was her love for her child. "I took motherhood and turned it on its head and I think that was great fun. Mrs. Voorhees was the mother I'd always wanted—a mother who would have killed for her kids."[7] Miller was unhappy about the filmmakers' decision to make Jason Voorhees the killer in the sequels. "Jason was dead from the very beginning. He was a victim, not a villain."[7]

The idea of Jason appearing at the end of the film was initially not used in the original script; in Miller's final draft, the film ended with Alice merely floating on the lake.[8] Jason's appearance was actually suggested by makeup designer Tom Savini.[8] Savini stated that "The whole reason for the cliffhanger at the end was I had just seen Carrie, so we thought that we need a 'chair jumper' like that, and I said, 'let's bring in Jason'".[9]

Casting

A New York-based firm, headed by Julie Hughes and Barry Moss, was hired to find eight young actors to play the camp's staff members. Cunningham admits that he was not looking for "great actors," but anyone that was likable, and appeared to be a responsible camp counselor.[10] The way Cunningham saw it, the actors would need to look good, read the dialogue somewhat well, and work cheap. Moss and Hughes were happy to find four actors, Kevin Bacon, Laurie Bartram, Peter Brouwer, and Adrienne King, who had previously appeared on soap operas.[10] The role of Alice Hardy was set up as an open casting call, a publicity stunt used to attract more attention to the film. The producers originally wanted Sally Field for the role of Alice, but realized that they could not afford an established high-profile actress and went for unknowns instead. According to Adrienne King. "originally, [the producers] were looking really hard for a name actress to play Alice. They finally realized that even if they could find somebody like that who was willing to do it, they wouldn't be able to afford her, so they decided to go with new talent instead."[11] King earned an audition primarily because she was the friend of someone working in Moss and Hughes's office, and Cunningham felt she embodied the qualities of Alice.[12] After she auditioned, Moss recalls Cunningham commenting that they saved the best actress for last.[13] As Cunningham explains, he was looking for people that could behave naturally, and King was able to show that to him in the audition.[13]

I didn't even really think of this movie as a horror film. To me, this was a small independent film about carefree teenagers who are having a rip-roaring time at a summer camp where they happen to be working as counselors. Then they just happen to get killed.

—Jeannine Taylor on how she viewed Friday the 13th[13]

With King cast in the role of lead heroine Alice, Laurie Bartram was hired to play Brenda. Kevin Bacon, Mark Nelson and Jeannine Taylor, who had known each other prior to the film, were cast as Jack, Ned, and Marcie respectively. It is Bacon and Nelson's contention that, because the three already knew each other, they already had the specific chemistry the casting director was looking for in the roles of Jack, Ned, and Marcie.[10] Taylor has stated that Hughes and Moss were highly regarded while she was an actress, so when they offered her an audition she felt that, whatever the part, it would "be a good opportunity."[13]

Friday the 13th was Nelson's first feature film, and when he went in for his first audition, the only thing he was given to read were some comedic scenes. Nelson received a call back for a second audition, which required him to wear a bathing suit, which, Nelson acknowledges, made him start to wonder if something was off about this film. He did not fully realize what was going on until he got the part and was given the full script to read. Nelson explains, "It certainly was not a straight dramatic role, and it was only after they offered me the part that they gave me the full script to read and I realized how much blood was in it."[13] Nelson believes that Ned used humor to hide his insecurities, especially around Brenda, whom the actor believes Ned was attracted to. Nelson recalls an early draft of the script stating that Ned suffered from polio, and his legs were deformed while his upper body was muscular.[14] Ned is believed to have given birth to the "practical joker victim" of horror films.[15] According to author David Grove, there was no equivalent character in John Carpenter's Halloween, or Bob Clark's Black Christmas before that. He served as a model for the slasher films that would follow Friday the 13th.[15]

I went in to audition for [Moss and Hughes] for something else. They said, "You know, Robbi, you're not really right for this, but there's a movie called Friday the 13th and they need an adorable camp counselor."

—Robbi Morgan on how she obtained the role of Annie[13]

The part of Bill was given to Harry Crosby, son of Bing Crosby.[16] Robbi Morgan, who played Annie, was not auditioning for the film when she was offered the role; while in her office, Hughes looked at Morgan and proclaimed, "You're a camp counselor." The next day, Morgan was on the set.[10] Morgan only appeared on set for a day to shoot all her scenes. Rex Everhart, who portrayed Enos, did not film the truck scenes with Morgan, so she had to either act with an imaginary Enos, or exchange dialogue with Taso Stavrakis—Savini's assistant—who would sit in the truck with her.[17] It was Peter Brouwer's girlfriend that helped him land a role on Friday the 13th. After recently being written off the show Love of Life, Brouwer moved back to Connecticut to look for work. Learning that his girlfriend was working as an assistant director for Friday the 13th, Brouwer asked about any openings. Initially told casting was looking for big stars to fill the role of Steve Christy, it was not until Sean Cunningham dropped by to deliver a message to Brouwer's girlfriend, and saw him working in a garden, that Brouwer was hired.[10]

Estelle Parsons was initially asked to portray the film's killer, Mrs. Voorhees, but declined with her agent citing that the film was too violent, and did not know what kind of actress would play such a part. Shelley Winters was also offered the part, but turned it down.[18] Hughes and Moss sent a copy of the script to Betsy Palmer, in hopes that she would accept the part. Palmer could not understand why someone would want her for a part in a horror film, as she had previously starred in films such as Mister Roberts, The Angry Man, and The Tin Star. Palmer only agreed to play the role because she needed to buy a new car, even when she believed the film to "be a piece of shit."[10] Stavrakis subbed for Betsy Palmer as well, which involved Morgan's character being chased through the woods by Mrs. Voorhees, although the audience only sees a pair of legs running after Morgan. Palmer had just arrived in town when those scenes were about to be filmed, and was not in the physical shape necessary to chase Morgan around the woods. Morgan's training as an acrobat assisted her in these scenes, as her character was required to leap out of a moving jeep when she discovers that Mrs. Voorhees does not intend to take her to the camp.[17] Betsy Palmer explains how she developed the character of Mrs. Voorhees:

Being an actress who uses the Stanislavsky method, I always try to find details about my character. With Pamela ... I began with a class ring that I remember reading in the script that she'd worn. Starting with that, I traced Pamela back to my own high school days in the early 1940s. So it's 1944, a very conservative time, and Pamela has a steady boyfriend. They have sex—which is very bad of course—and Pamela soon gets pregnant with Jason. The father takes off and when Pamela tells her parents, they disown her because having ... babies out of wedlock isn't something that good girls do. I think she took Jason and raised him the best she could, but he turned out to be a very strange boy. [She took] lots of odd jobs and one of those jobs was as a cook at a summer camp. Then Jason drowns and her whole world collapses. What were the counselors doing instead of watching Jason? They were having sex, which is the way that she got into trouble. From that point on, Pamela became very psychotic and puritanical in her attitudes as she was determined to kill all of the immoral camp counselors.[19]

Cunningham wanted to make the Mrs. Voorhees character "terrifying", and to that end he believed it was important that Palmer not act "over the top." There was also the fear that Palmer's past credits, as more of a wholesome character, would make it difficult to believe she could be scary.[20] Palmer was paid $1000 per day for her ten days on set.[16] Ari Lehman, who had previously auditioned for Cunningham's Manny's Orphans, failing to get the part, was determined to land the role of Jason Voorhees. According to Lehman, he went in very intense and afterward Cunningham told him he was perfect for the part.[10] In addition to the main cast, Walt Gorney came on as "Crazy Ralph", the town's soothsayer. The character of Crazy Ralph was meant to establish two functions: foreshadow the events to come, and insinuate that he could actually be the murderer. Cunningham has stated that he was apprehensive about including the character, and is not sure if he accomplished his goal of creating a new suspect.[13]

Filming

The film was shot in and around the townships of Hardwick, Blairstown, and Hope, in Warren County, New Jersey in September 1979. The camp scenes were shot on a working Boy Scout camp, Camp No-Be-Bo-Sco which is located in Hardwick.[21] The camp is still standing and still operates as a summer camp.[22][23]

Tom Savini was hired to design the film's special effects based upon his work in George A. Romero's Dawn of the Dead (1978).[16] Savini's design contributions included crafting the effects of Marcie's axe wound to the face, the arrow penetrating Jack's throat, and Mrs. Voorhees's decapitation by the machete.[16] The cinematography in the film employs recurrent point-of-view shots from the perspective of the villain.[24] A live snake was killed during filming as part of a scene where Alice discovers it in her cabin. The handler was not made aware of the plans to kill the snake.[25]

During the filming of the fight sequences between King and Palmer's characters, Palmer suggested rehearsing the scene based on her theater training: "I said to Adrienne that night, 'Why don't we rehearse this scene, I have to slap you,' because on stage when you slap somebody, you slap them."[21] While rehearsing, Palmer slapped King in the face, and she began crying: "She collapsed to the floor, crying, 'Sean! [Cunningham] She hit me.' I said, 'Well, of course I hit her, we were rehearsing the scene.' He said, 'No, no, no Betsy, we don't hit people in movies. We miss them.'"[21]

Music

| Friday the 13th | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | January 13, 2012 |

| Recorded | 1980 |

| Genre | Film score |

| Length | 43:41 |

| Label | Gramavision Records La-La Land Records |

When Harry Manfredini began working on the musical score, the decision was made to only play music when the killer was actually present so as to not "manipulate the audience".[26] Manfredini pointed out the lack of music for certain scenes: "There's a scene where one of the girls ... is setting up the archery area ... One of the guys shoots an arrow into the target and just misses her. It's a huge scare, but if you notice, there's no music. That was a choice."[26] Manfredini also noted that when something was going to happen, the music would cut off so that the audience would relax a bit, and the scare would be that much more effective.

Because the killer, Mrs. Voorhees, appears onscreen only during the final scenes of the film, Manfredini had the job of creating a score that would represent the killer in her absence.[26] Manfredini borrows from the 1975 film Jaws, where the shark is likewise not seen for the majority of the film but the motif created by John Williams cued the audience to the shark's invisible menace.[27] Sean S. Cunningham sought a chorus, but the budget would not allow it. While listening to a Krzysztof Penderecki piece of music, which contained a chorus with "striking pronunciations", Manfredini was inspired to recreate a similar sound. He came up with the sound "ki ki ki, ma ma ma" from the final reel when Mrs. Voorhees arrives and is reciting "Kill her, mommy!" The "ki" comes from "kill", and the "ma" from "mommy". To achieve the unique sound he wanted for the film, Manfredini spoke the two words "harshly, distinctly and rhythmically into a microphone" and ran them into an echo reverberation machine.[26] Manfredini finished the original score after a couple of weeks, and then recorded the score in a friend's basement.[27] Victor Miller and assistant editor Jay Keuper have commented on how memorable the music is, with Keuper describing it as "iconographic". Manfredini says, "Everybody thinks it's cha, cha, cha. I'm like, 'Cha, cha, cha? What are you talking about?'"[28]

In 1982, Gramavision Records released an LP record of selected pieces of Harry Manfredini's scores from the first three Friday the 13th films.[29] On 13 January 2012, La-La Land Records released a limited edition 6-CD boxset containing Manfredini's scores from the first six films. It sold out in less than 24 hours.[30]

Release

Distribution

A bidding war over distribution rights to the film ensued in 1980 between Paramount Pictures, Warner Bros., and United Artists.[31] Paramount executive Frank Mancuso, Sr. recalled: "The minute we saw Friday the 13th, we knew we had a hit."[31] Paramount ultimately purchased domestic distribution rights for Friday the 13th for $1.5 million.[31] Based on the success of recently released horror films (such as Halloween) and the low budget of the film, the studio deemed it a "low-risk" release in terms of profitability.[32] It was the first independent slasher film to be acquired by a major motion picture studio.[33] Paramount spent approximately $500,000 in advertisements for the film, and then an additional $500,000 when the film began performing well at the box office.[34]

Marketing

A full one-sheet poster, featuring a group of teenagers imposed beneath the silhouette of a knife-wielding figure, was designed by artist Alex Ebel to promote the film's U.S. release.[35] Scholar Richard Nowell has observed that the poster and marketing campaign presented Friday the 13th as a "light-hearted" and "youth-oriented" horror film in an attempt to draw interest from America's prime theater-going demographic of young adults and teenagers.[36] Warner Bros. secured distribution rights to the film in international markets.[31][37]

Home media

Friday the 13th was first released on DVD in the United States by Paramount Home Entertainment on October 19, 1999.[1] The disc sold 32,497 units.[1] On February 3, 2009, Paramount released the film again on DVD and Blu-ray in an unrated uncut, for the first time in the United States (previous VHS, LaserDisc and DVD releases included the R-rated theatrical version).[38] The uncut version of the film contains approximately 11 seconds of previously unreleased footage.[38]

In 2011, the uncut version of Friday the 13th was released in a 4-disc DVD collection with the first three sequels.[39] It was again included in two Blu-ray sets: Friday the 13th: The Complete Collection, released in 2013 and Friday the 13th: The Ultimate Collection, in 2018.[40] Paramount's Blu-ray was re-released as a 40th Anniversary Limited Edition steelbook in 2020.[41] In 2020, to celebrate the film's 40th anniversary, Shout! Factory released a 4K scan of the original film, as well as parts 2-4, in a complete series box set.

Reception

Box office

Friday the 13th opened theatrically on May 9, 1980 across the United States, ultimately expanding its release to 1,127 theaters.[1] It earned $5,816,321 in its opening weekend, before finishing domestically with $39,754,601,[42] with a total of 14,778,700 admissions.[1] It was the 18th highest-grossing film that year, facing competition from other high-profile horror releases such as The Shining, Dressed To Kill, The Fog, and Prom Night.[43] The worldwide gross for the film was $59,754,601.[44][45] Of the seventeen films distributed by Paramount in 1980, only one, Airplane!, returned more profits than Friday the 13th.[46]

Friday the 13th was released internationally, which was unusual for an independent film with, at the time, no well-recognized or bankable actors; aside from well-known television and movie actress Betsy Palmer.[47] The film would take in approximately $20 million in international box office receipts.[48] Not factoring in international sales, or the cross-over film with A Nightmare on Elm Street's Freddy Krueger, the original Friday the 13th is the highest-grossing film of the franchise.[49]

To provide context with the box office gross of films in 2014, the cost of making and promoting Friday the 13th—which includes the $550,000 budget and the $1 million in advertisement—is approximately $4.5 million. With regard to the US box office gross, the film would have made $177.72 million in adjusted 2017 dollars.[50] On July 13, 2007, Friday the 13th was screened for the first time on Blairstown's Main Street in the very theater which appears shortly after the opening credits.[23] Overflowing crowds forced the Blairstown Theater Festival, the sponsoring organization, to add an extra screening. A 30th Anniversary Edition was released on March 10, 2010.[51] A 35th-anniversary screening was held in the Griffith Park Zoo as part of the Great Horror Campout on March 13, 2015.[52]

Critical response

Original theatrical reviews

Linda Gross of the Los Angeles Times referred to the film as a "silly, boring, youth-geared horror movie," though she praised Manfredini's "nervous musical score," the cinematography, as well as the performances, which she deemed "natural and appealing," particularly from Taylor, Bacon, Nelson, and Bartram.[53] Variety, however, deemed the film "low budget in the worst sense—with no apparent talent or intelligence to offset its technical inadequacies—Friday the 13th has nothing to exploit but its title."[54] The Miami News's Bill von Maurer praised Cunningham's "low-key" direction, but noted: "After building terrific suspense and turning over the audience's stomachs, he doesn't quite know where to go from there. The movie begins to sag in the middle and the expectations he has built up begin to sour a bit."[55] Lou Cedrone of The Baltimore Evening Sun referred to the film as "a shamelessly bad film, but then Cunningham knows this. This is sad."[56]

Many critics compared the film unfavorably against John Carpenter's Halloween, among them Marylynn Uricchio of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, who added: "Friday the 13th is minimal on plot, suspense, and characterization. It's not very original or very scary, but it is very low-budget."[57] Dick Shippy of the Akron Beacon Journal similarly suggested that Carpenter's Halloween played "like Hitchcock when compared to Cunningham's dreadful tale of butchery."[58] The Burlington Free Press's Mike Hughes wrote that the film "copies everything, that is, except the quality" of Halloween, concluding: "The lowest point of the movie comes near the end, when it exploits the genuine grief and madness of the villain. By then, things simply aren't fun anymore."[59] Ron Cowan of the Statesman Journal noted the film as a "routine 'endangered teenagers' exploitation movie", adding that "Cunningham betrays a rather plodding approach to suspense for most of the film, sometimes allowing his camera to act as the killer, sometimes as the victim. And the victims, of course, deliberately put themselves in peril."[60]

A significant number of reviews criticized the film for its depiction of violence: The Hollywood Reporter derided the film, writing: "Gruesome violence, in which throats are slashed and heads are split open in realistic detail, is the sum content of Friday the 13th, a sick and sickening low budget feature that is being released by Paramount. It's blatant exploitation of the lowest order."[61] Michael Blowen of The Boston Globe similarly referred to the film as "nauseating," warning audiences: "Unless your idea of a good time is to watch a woman have her head split by an ax or a man stuck to a door with arrows, you should stay away from Friday the 13th. It's bad luck."[62] The film's most vocal detractor was Gene Siskel, who in his review called Cunningham "one of the most despicable creatures ever to infest the movie business."[63] He also published the address for Charles Bluhdorn, the chairman of the board of Gulf+Western, which owned Paramount, as well as Betsy Palmer's home city and encouraged fellow detractors to write to them and express their contempt for the film. Attempting to convince people not to see it, he even gave away the ending.[64] Siskel and Roger Ebert spent an entire episode of their TV show berating the film (and other slasher films of the time) because they felt it would make audiences root for the killer.[65] Leonard Maltin initially awarded the film one star, or 'BOMB', but later changed his mind and awarded the film a star and-a-half "simply because it's slightly better than Part 2" and called it a "gory, cardboard thriller...That younger viewers made it a box-office juggernaut is one more clue as to why SAT scores keep declining. Still, any movie that spawns this many sequels must have done something right".[66]

Contemporary

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Friday the 13th holds an approval rating of 63% based on 56 reviews, with an average rating of 5.80/10. The site's critics consensus reads: "Rather quaint by today's standards, Friday the 13th still has its share of bloody surprises and a '70s-holdover aesthetic to slightly compel."[67] On Metacritic, it has a weighted average score of 22 out of 100, based on 11 critics, indicating "generally unfavorable reviews."[68] It was nominated for Worst Picture at the 1st Golden Raspberry Awards, and Palmer was nominated for Worst Supporting Actress.[69]

Bill Steele of IFC ranked the film the second-best entry in the series, after Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981).[70] Critic Kim Newman, in a 2000 review, awarded the film two out of five stars, referring to it as "a pallid Halloween rip-off, with a mediocre shock count and a botched ending... As the bodies pile up amongst this testy crowd of horny teens, there remains a vacant hole were [sic] someone scary should be. In a strange way, this film stands unique amongst all slasher films as one where the killer is nearly intangible."[71] Jeremiah Kipp of Slant Magazine reviewed the film in 2009, noting "a kind of minimalism at work, eschewing anything special in terms of mood, pacing, character, plot, and tension."[72] Further commenting on the revelation of the killer's identity, Kipp observed:

The murderer turns out to be a middle-aged woman named Mrs. Voorhees (Betsy Palmer) with a butch haircut and a gigantic bulky sweater, whose line readings are akin to nails on a chalkboard ("They were making love while that boy drowned! His name was Jason!") and a predilection for speaking to herself in the mincing voice of her dead child ("Kill her, Mommy! Kill her!"). It's only in this last 20-minute appearance of this scene-stealing harpy (not to mention the memorable cameo by her rotting zombie son) that Friday the 13th becomes memorable as high camp.[72]

Why did it make such a splash? Theories abound, but here's mine: Friday the 13th succeeded because it was brazen enough to steal so many tricks from the many brilliant horror films that came before it.

—Critic Scott Meslow on the film's legacy[73]

In 2012, Bill Gibron of PopMatters wrote of the film: "This movie feels at least twice as long as its 90-minute running time and not always in a good way. There are far too many pointless pauses between the bloodletting. On the positive side, Tom Savini's make-up work is flawless, and Betsy Palmer's turn as big bad Pamela V. has to go down in history as one of the meanest 'mothers' in the entire horror genre. For those who think it's a classic–think again. Of a type? Absolutely. Of faultless movie macabre? No way."[74]

Scott Meslow of The Week reviewed the film in 2015, assessing its original critical reception in a contemporary context: "Before it became an absurdly prolific franchise, Friday the 13th was a cynical, one-off attempt to make a fast buck on a sleazy slasher movie that accidentally ended up spawning a decades-spanning, multimillion-dollar phenomenon... What's most striking about Friday the 13th is how little regard anyone but its fans seem to have for it."[73]

Analysis

Teen sexuality

Film scholar Williams views Friday the 13th as "symptomatic of its era," particularly Reagan-era America, and part of a trajectory of films such as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and Race with the Devil (1975), which "exemplify a particular apocalyptic vision moving from disclosing family contradictions to self-indulgent nihilism."[75] The film's recurring use of point-of-view shots from the killer's perspective have been noted by scholars such as Philip Dimare as "inherently voyeuristic."[24] Dimare regards the film as a "cautionary tale that succeeds in warning against the sexual impropriety even as it fetishizes violent transgression."[24]

Film critic Timothy Shary notes in his book Teen Movies: American Youth on Screen (2012) that where Halloween introduced a "more subtle sexual curiosity within its morbid moral lesson," films such as Friday the 13th "capitali[zed] on the reactionary aspect of teen sexuality, slaughtering wholesale those youth who deigned to cross the threshold of sexual awareness."[76] Commenting on the film's violence and sexuality, film scholar David J. Hogan notes that, "throughout the film, teenage boys are hideously dispatched, but not with the same buildup and attention to detail that Cunningham and makeup wiz Tom Savini reserved for nubile young girls."[77]

Gender of villain

The film has spurred critical discussion in regard to its villain being female, a plot point examined at length by film scholar Carol J. Clover in her book Men, Women, and Chainsaws. Clover notes the revelation of Pamela Voorhees as the killer as "the most dramatic case of pulling out the gender rug" in horror film history.[78] Commenting on the first-person point-of-view shots from the killer, Clover writes: "'We' [the audience] stalk and kill a number of teenagers over the course of an hour of movie time without even knowing who 'we' are; we are invited, by conventional expectation and by glimpses of 'our' own bodily parts—a heavily booted foot, a roughly gloved hand—to suppose that 'we' are male, but 'we' are revealed, at the film's end, as a woman."[78]

On the killer's identity, Dimare has noted:

Because Cunningham avoids revealing anything about the psychotic killer beyond the fact that the figure is dressed in men's gloves and boots, the audience assumes the slayer is a man... Cunningham sustains the eerie indeterminacy of the killer's age, social status, and gender deep into his film. The use of this cinematic process of abstraction allows the film to linger over the ambiguous nature of evil until 'sits [sic] climactic last act.[24]

Legacy

Contemporary scholars in film criticism, such as Tony Williams, have credited Friday the 13th for initiating the subgenre of the "stalker" or slasher film.[75] Cultural critic Graham Thompson also considers the film as a template, along with John Carpenter's Halloween (1978), that "instigated a rush" of films of its type, in which young people away from supervision are systematically stalked and murdered by a masked villain.[79] While critical reception of the film has been varied in the years since its release, it has attained a significant cult following.[80] In 2017, Complex ranked the film ninth in a list of the best slasher films of all time.[81]

Film scholar Matt Hills wrote of the film's legacy: "Friday the 13th has not just been critically positioned as intellectually lacking, it has been othered and devalued in line with the conventional aesthetic norms of the academy and official film culture, said to lack originality and artfulness, to possess no nominated or recognized auteur, and to be grossly sensationalist in its focus on Tom Savini's gory special effects."[82] The film was nominated in 2001 for AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills.[83]

In April 2018, Camp No-Be-Bo-Sco, where the film was shot, held "Crystal Lake Tours," an event dedicated to the making of the film which brought attendees to nine of the filming locations on the property.[84] The event was attended by actress Adrienne King, who recounted the making of the film to fans.[84]

Other media

Sequel and franchise

As of 2018, Friday the 13th has spawned ten sequels, including a crossover film with A Nightmare on Elm Street villain Freddy Krueger.[85] Friday the 13th Part II introduced Jason Voorhees, the son of Mrs. Voorhees, as the primary antagonist, which would continue for the remaining sequels (with exception of the fifth movie) and related works.[86] Most of the sequels were filmed on larger budgets than the original. For comparison, Friday the 13th had a budget of $550,000, while the first sequel was given a budget of $1.25 million.[87] At the time of its release, Freddy vs. Jason had the largest budget, at $30 million.[88] All of the sequels repeated the premise of the original, so the filmmakers made tweaks to provide freshness. Changes involved an addition to the title—as opposed to a number attached to the end—like "The Final Chapter" and "Jason Takes Manhattan", or filming the movie in 3-D, as Miner did for Friday the 13th Part III (1982).[89] One major addition that would affect the entire film series was the addition of Jason's hockey mask in the third film; this mask would become one of the most recognizable images in popular culture.[90]

A reboot to Friday the 13th was released theatrically in February 2009, with Freddy vs. Jason writers Damian Shannon and Mark Swift hired to script the new film.[91] The film focused on Jason Voorhees, along with his trademark hockey mask.[92] The film was produced by Michael Bay, Andrew Form and Brad Fuller through Bay's production company Platinum Dunes, for New Line Cinema.[91] In November 2007, Marcus Nispel, director of the 2003 remake of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, was hired to direct.[93] The film had its United States release on February 13, 2009.[94]

Novelization

In 1987, seven years after the release of the motion picture, Simon Hawke produced a novelization of Friday the 13th. One of the few additions to the book was Mrs. Voorhees begging the Christy family to take her back after the loss of her son; they agreed.[95] Another addition in the novel is more understanding in Mrs. Voorhees' actions. Hawke felt the character had attempted to move on when Jason died, but her psychosis got the best of her. When Steve Christy reopened the camp, Mrs. Voorhees saw it as a chance that what happened to her son could happen again. Her murders were against the counselors, because she saw them all as responsible for Jason's death.[96]

Comic books

A number of scenes from the film were recreated in Friday the 13th: Pamela's Tale, a two-issue comic book prequel released by WildStorm in 2007. In 2016, the book On Location in Blairstown: The Making of Friday the 13th was released detailing the planning and filming of the movie.[97]

Video game

In 2007, Xendex released game-adaptation movie Friday the 13th for mobile phones. In the game, the player plays as Annie Phillips (but unlike in the film she doesn`t die), one of the counselors at Camp Crystal Lake. While the staff is preparing the camp for its first summer weekend, an "unknown stalker" begins murdering each of them. The player must discover the truth and escape the camp alive.[98]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bracke 2006, p. 314.

- ↑ "Friday the 13th (1980) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Grove 2005, pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 3 Bracke 2006, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 Bracke 2006, p. 17.

- ↑ Grove 2005, pp. 15–16.

- 1 2 Miller, Victor. "Frequently Asked Questions". Victor Miller Official Site. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

I have a major problem with all of them because they made Jason the villain. I still believe that the best part of my screenplay was the fact that a mother figure was the serial killer—working from a horribly twisted desire to avenge the senseless death of her son, Jason. Jason was dead from the very beginning. He was a victim, not a villain.

- 1 2 Bracke 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ "Jason Voorhees: From mama's boy to his own man". New York Daily News. October 19, 2006. Archived from the original on November 14, 2006. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Grove 2005, pp. 21–28.

- ↑ Marc Shapiro (June 1989). "The Women of Crystal Lake Part One". Fangoria. No. 83. pp. 18–21.

- ↑ Norman 2014, p. 84.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bracke 2006, pp. 19–21.

- ↑ Grove 2005, pp. 36–39.

- 1 2 Grove 2005, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 Vancheri, Barbara (February 13, 2009). "Freaky Friday". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. pp. D–1, D-5. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Grove 2005, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ "'On Location in Blairstown: The Making of Friday the 13th': Author Q&A". Entertainment Weekly.

- ↑ Grove 2005, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Grove 2005, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 Hawkes, Rebecca (October 13, 2017). "Friday the 13th: nine things you didn't know about the movie". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ↑ Cummins, Emily (May 5, 2014). "Blairstown Theatre to screen latest horror film by local director". NJ.com. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016.

- 1 2 "Blairstown Theater Festival". Blairstown Theater. Archived from the original on July 12, 2007. Retrieved March 2, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Dimare 2011, p. 186.

- ↑ Wilhelmi, Jack; Lealos, Shawn S. (September 13, 2023). "Friday The 13th Controversy: Did They Kill A Real Snake?". Screen Rants. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "Slasherama interview with Harry Manfredini". Slasherama. Archived from the original on May 11, 2006. Retrieved October 28, 2007.

- 1 2 Bracke 2006, p. 39.

- ↑ Miller, Victor; Keuper, Jay; Manfredini, Harry (1980). "Return to Crystal Lake: Making of Friday the 13th" Friday the 13th DVD (DVD – region 2). United States: Warner Bros.

- ↑ Bracke 2006, p. 94.

- ↑ "LA LA LAND RECORDS, Friday the 13th". lalalandrecords.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Nowell 2010, p. 134.

- ↑ Nowell 2010, pp. 135–137.

- ↑ McCarty 1984, p. 2.

- ↑ Grove 2005, p. 59.

- ↑ Nowell 2010, p. 139.

- ↑ Nowell 2010, pp. 145–147.

- ↑ Nowell, Richard (2011). ""The Ambitions of Most Independent Filmmakers": Indie Production, the Majors, and Friday the 13th (1980)". Journal of Film and Video. 63 (2): 28–44. doi:10.5406/jfilmvideo.63.2.0028. S2CID 194097731.

- 1 2 McGaughy, Cameron (February 3, 2009). "Friday the 13th: Uncut Deluxe Edition (1980)". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Buy Movies at Movies Unlimited - The Movie Collector's Site". moviesunlimited.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ↑ Squires, John (November 30, 2017). "New 'Friday the 13th' Blu-ray Collection Coming Next Year; Full Details". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Squires, John. "Paramount Releasing 'Friday the 13th' 40th Anniversary Steelbook Blu-ray in May". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ↑ Grove 2005, p. 60.

- ↑ Nowell 2010, pp. 199–202.

- ↑ "Box Office Information for Friday the 13th". The Numbers. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ↑ "1980". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ↑ Nowell 2010, p. 138.

- ↑ Rockoff 2002, p. 18.

- ↑ "Friday the 13th - Box Office Data, DVD Sales, Movie News, Cast Information". the-numbers.com. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Friday the 13th Movies at the Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Tom's Inflation Calculator". Halfhill.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ↑ Serafini, Matt (January 29, 2010). "Fantastic Friday the 13th Anniversary Item Coming". Dread Central. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Moore, Debi (February 23, 2015). "Great Horror Campout Launches Movie Night Under the Stars March 13th in Los Angeles". Dread Central. Archived from the original on February 5, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- ↑ Gross, Linda (May 15, 1980). "'Friday the 13th': Encamped in Gore". Los Angeles Times. p. 7. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Friday the 13th". Variety. December 31, 1979. Archived from the original on April 14, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ↑ Von Maurer, Bill. "'Friday the 13th' will scare the bejabbers out of you". The Miami News. Miami, Florida. p. 8A. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Cedrone, Lou (May 14, 1980). "Adams is good for laughs; '13th' is good for nothing". The Baltimore Evening Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. p. 8A. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Uricchio, Marylynn. "'Friday the 13th': Unlucky Day for Moviegoers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. p. 16. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Shippy, Dick (May 15, 1980). "Sex and slaughter in wholesale doses". Akron Beacon Journal. p. F6. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Hughes, Mike (May 20, 1980). "Thriller Badly Copies 'Halloween'". The Burlington Free Press. Burlington, Vermont. p. 4D. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Cowan, Ron. "'Friday the 13th' bodes bad luck". Statesman Journal. Salem, Oregon. p. 5C. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ The Hollywood Reporter Staff (November 1, 2014) [1980]. "'Friday the 13th': THR's 1980 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ↑ Blowen, Michael. "Bloody 'Friday' is nauseating". The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. p. 12. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Bracke 2006, p. 45.

- ↑ Siskel, Gene (May 12, 1980). "'Friday the 13th': More bad luck". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. p. A3.

- ↑ Hewitt, Chris; Smith, Adam. "Freddy V Jason". Empire (March 2009).

- ↑ Maltin 2000, p. 491.

- ↑ "Friday the 13th (1980)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixer. Archived from the original on November 27, 2017. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Friday the 13th (1980) Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ↑ Fitz-Gerald, Sean. "7 Worst-Picture Razzie Contenders That Are Actually Good". Thrillist. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ↑ Steele, Bill (July 29, 2016). "Every Friday the 13th Movie Ranked". IFC. Archived from the original on September 4, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Newman, Kim (January 1, 2000). "Friday the 13th". Empire. Archived from the original on December 29, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- 1 2 Kipp, Jeremiah (February 4, 2009). "Friday the 13th". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- 1 2 Meslow, Scott (June 14, 2015). "How Friday the 13th accidentally perfected the slasher movie". The Week. Archived from the original on August 5, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ↑ Gibron, Bill (July 13, 2012). "Dissecting the 'Friday the 13th' Franchise". PopMatters. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- 1 2 Williams 2015, p. 185.

- ↑ Shary 2012, p. 54.

- ↑ Hogan 2016, p. 254.

- 1 2 Clover 1993, p. 56.

- ↑ Thompson 2007, p. 102.

- ↑ Hills 2007, p. 236.

- ↑ Barone, Matt (October 23, 2017). "The Best Slasher Films of All Time". Complex. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ↑ Hills 2007, p. 232.

- ↑ "List of top 400 heart-pounding thrillers" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- 1 2 Squires, John (April 17, 2018). "We Spent Friday the 13th at the Real Camp Crystal Lake in New Jersey". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Robinson 2012, p. 201.

- ↑ Kendrick 2017, p. 325.

- ↑ Bracke 2006, pp. 314–15.

- ↑ "Freddy Vs. Jason (2003)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ↑ Bracke 2006, p. 73–74.

- ↑ Kemble, Gary (January 13, 2001). "Movie Minutiae: the Friday the 13th series (1980-?)". ABC. Archived from the original on January 15, 2006.

- 1 2 Kit, Borys (October 2, 2007). "Duo pumps new blood into 'Friday the 13th'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Platinum Confirmations: Near Dark, Friday the 13th Remakes". The Hollywood Reporter. October 3, 2007. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ↑ Kit, Borys (November 14, 2007). "Nispel scores a date with next 'Friday'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Young Jason Cast in Friday the 13th remake". FearNet. May 15, 2008. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008.

- ↑ Hawke 1987, pp. 164–168.

- ↑ Grove 2005, p. 50.

- ↑ Weird New Jersey. issue 46. April 2016. p. 50.

- ↑ "Friday the 13th (mobile phone game)". Xendex.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2008. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

Sources

- Bracke, Peter (2006). Crystal Lake Memories. United Kingdom: Titan Books. ISBN 1-84576-343-2.

- Clover, Carol (1993). Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00620-8.

- Dimare, Philip C. (2011). Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-598-84296-8.

- Falconer, Peter (2010). "Fresh Meat? Dissecting the Horror Movie Virgin". In McDonald, Tamar Jeffers (ed.). Virgin Territory: Representing Sexual Inexperience in Film. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 123–137. ISBN 978-0-814-33318-1.

- Grove, David (2005). Making Friday the 13th: The Legend of Camp Blood. United Kingdom: FAB Press. ISBN 1-903254-31-0.

- Hawke, Simon (1987). Friday the 13th. New York: Signet. ISBN 0-451-15089-9.

- Hills, Matt (2007). "The Friday the 13th Film Series as Other". Sleaze Artists: Cinema at the Margins of Taste, Style, and Politics. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. 219–239. ISBN 978-0-822-39019-0.

- Hogan, David J. (2016). Dark Romance: Sexuality in the Horror Film. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-46248-3.

- Kendrick, James (2017). "Slasher Films and Gore in the 1980s". In Benshoff, Harry M. (ed.). A Companion to the Horror Film. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 310–328. ISBN 978-1-119-33501-6.

- Maltin, Leonard (2000). Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide. New York: Signet Books. ISBN 0-451-19837-9.

- McCarty, John (1984). Splatter Movies: Breaking the Last Taboo of the Screen. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-75257-1.

- Norman, Jason (2014). Welcome to Our Nightmares: Behind the Scene with Today's Horror Actors. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-47986-3.

- Nowell, Richard (2010). Blood Money: A History of the First Teen Slasher Film Cycle. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-441-12496-8.

- Rockoff, Adam (2002). Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company. ISBN 0-7864-1227-5.

- Robinson, Jessica (2012). Life Lessons from Slasher Films. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-88502-8.

- Shary, Timothy (2012). Teen Movies: American Youth on Screen. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-50160-6.

- Thompson, Graham (2007). American Culture in the 1980s. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-748-62895-7.

- Williams, Tony (2015). Hearths of Darkness: The Family in the American Horror Film (Revised ed.). Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-628-46107-7.