Gainas (Greek: Γαϊνάς) was a Gothic leader who served the Eastern Roman Empire as magister militum during the reigns of Theodosius I and Arcadius.

Gainas began his military career as a common foot-soldier, but later commanded the barbarian contingent of Theodosius' army against the usurper Eugenius in 394. Under the command of Gainas, a man of "no lineage", was the young Alaric of the Balti dynasty.[1] In 395, Stilicho sent him with his troops, under the cover of strengthening the armies of the East, to depose the prefect Rufinus, who was hostile to Stilicho.[2] Gainas murdered Rufinus, but the eunuch Eutropius, who was likewise Stilicho's enemy, gained power. Gainas remained mostly unrewarded by the influential eunuch, which increased his resentment.[3]

In 399 he finally rose in stature by replacing magister militum Leo. This was after the latter failed to quell the insurrection of the Ostrogoths in Asia Minor, led by the chieftain Tribigild, who was also hostile to Eutropius. Gainas too failed to put down the invasions; according to some sources,[4] Gainas was conspiring with Tribigild in order to effect the downfall of Eutropius. After suffering repeated failures against the Ostrogoths, who continued devastating the provinces of Asia Minor, Gainas advised Arcadius to accept Tribigild's terms, which included the death of Eutropius. Gainas then showed his true colors, openly joining Tribigild with all his forces; he forced Arcadius to sign a treaty whereby the Goths would be allowed to settle in Thrace, entrusted with the defense of that frontier against the barbarians beyond the Danube.[5] Gainas proceeded to install his forces in Constantinople, where he ruled for several months. He attempted in effect to copy the success of Stilicho in the West and posed a danger to the survival of the Eastern Roman Empire. He deposed all the anti-Goth officials and had Eutropius executed, though he had previously only been banished; after the intervention of St. John Chrysostom the others were spared.[6]

While a somewhat competent military commander, the zealous Arian Gainas was patently unable to administer a city of 200–400,000 whose Greco-Roman populace intensely resented barbarian Goths and Arian Christians. Gainas' compromises with Tribigild led to rumors that he had colluded with Tribigild, his kinsman;[7] when he returned to Constantinople in 400, riots broke out. He attempted to evacuate his soldiers but even then the citizens of Constantinople managed to trap and kill 7,000 armed Goths.[6]

In response, Gainas and his forces attempted to flee back across the Hellespont, but their rag-tag ad hoc fleet was met and destroyed by another Goth in Imperial service, Fravitta, who was subsequently made consul for 401 but was later accused of treason and executed as well. After this battle, Gainas fled across the Danube and was caught by the Huns under Uldin. Gainas was killed, and his head was sent by Uldin to Arcadius c. 400 as a diplomatic gift.[6]

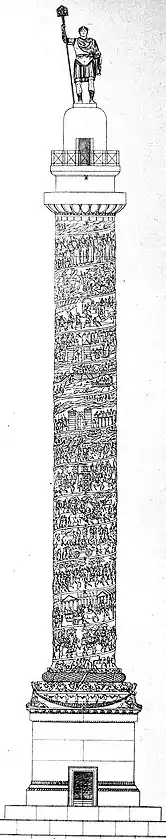

After the revolt, Arcadius erected the Column of Arcadius, on which friezes depicted his triumph over Gainas.

Gainas' usurpation is the subject of the Egyptian Tale and might also be the subject of the speech On Imperial Rule by Synesius of Cyrene who may have represented an anti-barbarian faction within the Byzantine nobility.

Herwig Wolfram, the historian of the Goths,[8] notes that the death of Gainas marks an end to the relatively pluralistic Gothic tribal development with independent warbands: "thereafter only two ethnogeneses were possible: that of the Roman Goths within the empire and that of the Hunnic Goths at its doorstep".

See also

Notes

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths (1979) 1988:138; Wolfram's summary of the career of Gainas and Tribigild: pp. 148–50.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, (The Modern Library, 1932), chap. XXIX., p. 1037

- ↑ Cameron and Long, Barbarian and Politics at the Court of Arcadius (1993):7-8

- ↑ Zosimus. See Gibbon, ch. XXXII., p. 1159, note 27

- ↑ Gibbon, pp. 1158, 1159

- 1 2 3 Friell, J. G. P.; Williams, Stephen Joseph (1999). The Rome that did not fall: the survival of the East in the fifth century. New York: Routledge. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-415-15403-0.

- ↑ The kinship of Gainas and Tribigild is inferred by Wolfram (1988:435 note 182) from Sozomen VIII..4.2, with the understanding that Sozomen may have meant merely that they were of the same tribe.

- ↑ Wolfram (1979) 1988:135.

References

- Zosimus Book V

- Socrates of Constantinople Book VI

- Sozomen Book VIII

- Theodoret Book V

- George of Alexandria, Life of St. Chrysostom, in Photios, Myriobiblon, 96

- Alan Cameron and Jacqueline Long, Barbarian and Politics at the Court of Arcadius, Berkeley et Los Angeles, 1993.

- Alexander Kazhdan (éd.), The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, 3 vols., Oxford University Press, 1991 (ISBN 0-19-504652-8)

- (fr) André Piganiol, L'Empire chrétien, PUF, Paris, 1972.

- Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths (1978) tr., 1988.