| Geb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Name in hieroglyphs | |||||

| Symbol | barley, goose, bull, viper | ||||

| Personal information | |||||

| Parents | Shu and Tefnut | ||||

| Siblings | Nut | ||||

| Consort | Nut, Tefnut, Renenutet (some sources) | ||||

| Offspring | Osiris, Isis, Set, Nephthys, Heru-ur, Nehebkau (in some myths) | ||||

| Equivalents | |||||

| Greek equivalent | Cronus | ||||

Geb was the Egyptian god of the earth[1] and a mythological member of the Ennead of Heliopolis. He could also be considered a father of snakes. It was believed in ancient Egypt that Geb's laughter created earthquakes[2] and that he allowed crops to grow.

Name

The name was pronounced as such from the Greek period onward and was originally wrongly read as Seb.[3]

Role and development

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

The oldest representation in a fragmentary relief of the god was as an anthropomorphic bearded being accompanied by his name, and dating from king Djoser's reign, during the Third Dynasty, and was found in Heliopolis. However, the god never received a temple of his own. In later times he could also be depicted as a ram, a bull or a crocodile (the latter in a vignette of the Book of the Dead of the lady Heryweben in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo).

Geb was frequently feared as father of snakes (one of the names for snake was s3-t3 – "son of the earth"). In one of the Coffin Text spells Geb was described as father of the mythological snake Nehebkau of primeval times. Geb also often occurs as a primeval divine king of Egypt from whom his son Osiris and his grandson Horus inherited the land after many conflicts with the disruptive god Set, brother and killer of Osiris. Geb could also be regarded as personified fertile earth and barren desert, the latter containing the dead or setting them free from their tombs, metaphorically described as "Geb opening his jaws", or imprisoning those there not worthy to go to the fertile North-Eastern heavenly Field of Reeds. In the latter case, one of his otherworldly attributes was an ominous jackal-headed stave (called wsr.t Mighty One') rising from the ground onto which enemies could be bound.

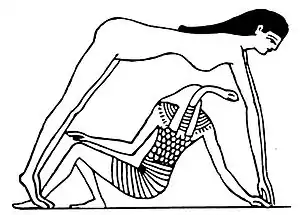

In the Heliopolitan Ennead (a group of nine gods created in the beginning by the one god Atum or Ra), Geb is the husband of Nut, the sky or visible daytime and nightly firmament, the son of the earlier primordial elements Tefnut (moisture) and Shu ("emptiness"), and the father to the four lesser gods of the system – Osiris, Seth, Isis and Nephthys. In this context, Geb was believed to have originally been engaged with Nut and had to be separated from her by Shu, god of the air.[4] Consequently, in mythological depictions, Geb was shown as a man reclining, sometimes with his phallus still pointed towards Nut. Geb and Nut together formed the permanent boundary between the primeval waters and the newly created world. [5]

As time progressed, the deity became more associated with the habitable land of Egypt and also as one of its early rulers. As a chthonic deity[6] he (like Min) became naturally associated with the underworld, fresh waters and with vegetation – barley being said to grow upon his ribs – and was depicted with plants and other green patches on his body.[7]

His association with vegetation, healing[7] and sometimes with the underworld and royalty brought Geb the occasional interpretation that he was the husband of Renenutet, a minor goddess of the harvest and also mythological caretaker (the meaning of her name is "nursing snake") of the young king in the shape of a cobra, who herself could also be regarded as the mother of Nehebkau, a primeval snake god associated with the underworld. He is also equated by classical authors as the Greek Titan Cronus.

Ptah and Ra, creator deities, usually begin the list of divine ancestors. There is speculation between Shu and Geb and who was the first god-king of Egypt. The story of how Shu, Geb, and Nut were separated in order to create the cosmos is now being interpreted in more human terms; exposing the hostility and sexual jealousy. Between the father-son jealousy and Shu rebelling against the divine order, Geb challenges Shu's leadership. Geb takes Shu's wife, Tefnut, as his chief queen, separating Shu from his sister-wife. Just as Shu had previously done to him. In the Book of the Heavenly Cow, it is implied that Geb is the heir of the departing sun god. After Geb passed on the throne to Osiris, his son, he then took on a role of a judge in the Divine Tribunal of the gods.[8]

Goose

Some Egyptologists (specifically Jan Bergman, Terence Duquesne or Richard H. Wilkinson) have stated that Geb was associated with a mythological divine creator goose who had laid a world egg from which the sun and/or the world had sprung. This theory is assumed to be incorrect and to be a result of confusing the divine name "Geb" with that of a Whitefronted Goose (Anser albifrons), also called originally gb(b): "lame one, stumbler".[9]

This bird-sign is used only as a phonogram in order to spell the name of the god (H.te Velde, in: Lexikon der Aegyptologie II, lemma: Geb). An alternative ancient name for this goose species was trp meaning similarly 'walk like a drunk', 'stumbler'. The Whitefronted Goose is never found as a cultic symbol or holy bird of Geb. The mythological creator 'goose' referred to above, was called Ngg wr "Great Honker" and always depicted as a Nile Goose/Fox Goose or Egyptian goose (Alopochen aegyptiacus) who ornithologically belongs to a separate genus and whose usual Egyptian name was smn, Coptic smon. A coloured vignette irrefutably depicts a Nile Goose with an opened beak (Ngg wr!) in a context of solar creation on a mythological papyrus dating from the 21st Dynasty.[10]

Similar images of this divine bird are to be found on temple walls (Karnak, Deir el-Bahari), showing a scene of the king standing on a papyrus raft and ritually plucking papyrus for the Theban god Amun-Re-Kamutef. The latter Theban creator god could be embodied in a Nile goose, but never in a Whitefronted Goose. In Underworld Books a diacritic goose-sign (most probably denoting then an Anser albifrons) was sometimes depicted on top of the head of a standing anonymous male anthropomorphic deity, pointing to Geb's identity. Geb himself was never depicted as a Nile Goose, as later was Amun, called on some New Kingdom stelae explicitly: "Amun, the beautiful smn- goose" (Nile Goose).[10]

The only clear pictorial confusion between the hieroglyphs of a Whitefronted Goose (in the normal hieroglyphic spelling of the name Geb, often followed by the additional -b-sign) and a Nile Goose in the spelling of the name Geb occurs in the rock cut tomb of the provincial governor Sarenput II (12th Dynasty, Middle Kingdom) on the Qubba el-Hawa desert-ridge (opposite Aswan), namely on the left (southern) wall near the open doorway, in the first line of the brightly painted funerary offering formula. This confusion is to be compared with the frequent hacking out by Akhenaten's agents of the sign of the Pintail Duck (meaning 'son') in the royal title 'Son of Re', especially in Theban temples, where they confused the duck sign with that of a Nile Goose regarded as a form of the then forbidden god Amon.[10]

Geb alias Cronus

In Greco-Roman Egypt, Geb was equated with the Greek titan Cronus, because he held a quite similar position in the Greek pantheon, as the father of the gods Zeus, Hades, and Poseidon, as Geb did in Egyptian mythology. This equation is particularly well attested in Tebtunis in the southern Fayyum: Geb and Cronus were here part of a local version of the cult of Sobek, the crocodile god.[11] The equation was shown on the one hand in the local iconography of the gods, in which Geb was depicted as a man with attributes of Cronus and Cronus with attributes of Geb.[12] On the other hand, the priests of the local main temple identified themselves in Egyptian texts as priests of "Soknebtunis-Geb", but in Greek texts as priests of "Soknebtunis-Cronus". Accordingly, Egyptian names formed with the name of the god Geb were just as popular among local villagers as Greek names derived from Cronus, especially the name "Kronion".[13]

References

- ↑ Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Handbook of Egyptian Mythology. Handbooks of World Mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 135. ISBN 1-57607-763-2.

- ↑ "Geb". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Wallis Budge, E. A. (1904). The Gods of the Egyptians: Studies in Egyptian Mythology. Kessinger publishing. ISBN 978-0766129863. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Meskell, Lynn Archaeologies of social life: age, class et cetera in ancient Egypt Wiley Blackwell (20 Oct 1999) ISBN 978-0-631-21299-7 p.103

- ↑ Van Dijk, Jacobus (1995). "Myth and Mythmaking in Ancient Egypt" (PDF). Jacobusvandijk. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ↑ Dunand, Francoise (2004). Gods and Men in Egypt 3000 BCE to 395 CE. Armand Colin. p. 345. ISBN 9780801488535.

- 1 2 Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames and Hudson. p. 105–106. ISBN 9780500051207.

- ↑ Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Handbook of Egyptian Mythology. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 76, 77, 78. ISBN 9781576072424.

- ↑ C. Wolterman, "On the Names of Birds and Hieroglyphic Sign-List G 22, G 35 and H 3" in: "Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch genootschap Ex Oriente Lux" no. 32 (1991–1992)(Leiden, 1993), p. 122, note 8

- 1 2 3 text: Drs. Carles Wolterman, Amstelveen, Holland

- ↑ Kockelmann, Holger (2017). Der Herr der Seen, Sümpfe und Flußläufe. Untersuchungen zum Gott Sobek und den ägyptischen Krokodilgötter-Kulten von den Anfängen bis zur Römerzeit [The lord of lakes, swamps and rivers. Studies on the god Sobek and the Egyptian crocodile god cults from the beginnings to Roman times] (in German). Vol. 1. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 81–88. ISBN 978-3-447-10810-2.

- ↑ Rondot, Vincent (2013). Derniers visages des dieux dʼÉgypte. Iconographies, panthéons et cultes dans le Fayoum hellénisé des IIe–IIIe siècles de notre ère [Last faces of the gods of Egypt. Iconographies, pantheons and cults in the Hellenized Fayoum of the 2nd–3rd centuries AD] (in French). Paris: Presses de lʼuniversité Paris-Sorbonne; Éditions du Louvre. pp. 75–80, 122–127, 241–246.

- ↑ Sippel, Benjamin (2020). Gottesdiener und Kamelzüchter: Das Alltags- und Sozialleben der Sobek-Priester im kaiserzeitlichen Fayum [Worshipers and camel breeders: The everyday and social life of the Sobek priests in Imperial Fayum] (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 73–78. ISBN 978-3-447-11485-1.