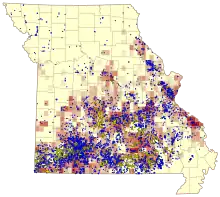

Missouri, a state near the geographical center of the United States, has three distinct physiographic divisions:

- a north-western upland plain or prairie region part of the Interior Plains' Central Lowland (areas Osage Plain 12f and Dissected Till Plains 12e) known as the northern plains

- a lowland in the extreme southeast bootheel region of Missouri, part of the Atlantic Plain known as the Mississippi Alluvial Plain (areas 3e) or the Mississippi embayment

- the Missouri portion of the Ozark Plateau (areas 14a and 14b) which lies between the Mississippi Alluvial Plain and the Central lowland.

The boundary between the northern plains and the Ozark region follows the Missouri River from its mouth at St. Louis to Columbia. This also corresponds to the southernmost extent of glaciation during the Pre-Illinoian Stage which destroyed the remnant plateau to the north but left the ancient landforms to the south unaltered. The Ozark boundary runs southwestward from there towards Joplin at the southeast corner of Kansas. The boundary between the Ozark and lowland regions runs southwest from Cape Girardeau on the Mississippi River to the Arkansas border just southwest of Poplar Bluff. Missouri borders eight other US States, more than any other state except Tennessee, which also borders eight states.

Regions

Northern Plains

The Dissected Till Plains portion of the northern plains region lies in the portion of the state north of the Missouri River, while the Osage plains portion extends into the southwestern portion of the state bordering the Ozark Plateau. Thus the northern plains covers an area slightly more than a third of the state. This region is a beautiful, rolling country, with a great abundance of streams.

It is more hilly and broken in its western half than in its eastern half. The elevation in the extreme northwestern Missouri is about 1,200 ft (370 m). and in the extreme northeastern portion about 500 ft (150 m)., while the rim of the region to the southeast, along the border of the Ozark region, has an elevation of about 900 ft (270 m). The valleys for the larger streams are about 250 to 300 ft (91 m) deep and sometimes 8 to 20 miles (32 km) wide with the country bordering them being the most broken of the region.

The smaller streams have so eroded the whole face of the country that little of the original surface plain is to be seen. The Mississippi River runs along the length of Missouri's eastern side and is skirted throughout by topographic relief of 400 to 600 ft (180 m). elevation.

Ozark Plateau

The Ozark region is essentially a low dome, with local faulting and minor undulations, dominated by a ridge or, more exactly, a relatively even belt of highland that runs from near the Mississippi river about Ste. Genevieve to McDonald County on the Arkansas border. High rocky bluffs rise precipitously on the Mississippi, sometimes to a height of 150 ft (46 m) or so above the water, from the mouth of the Meramec River to Ste. Genevieve. These mark where that river cuts the Ozark ridge. Across the Mississippi River, this ridge is continued by the Shawnee Hills in Illinois.

The elevations of the crests in Missouri vary from 1,100 to 1,700 ft (520 m). This second physiographic region comprises somewhat less than two-thirds of the area of the state. The Burlington escarpment of Mississippian rocks, which in places is as much as 250 to 300 ft (91 m) in height, runs along the western edge of the Ordovician formations and divides the region into an eastern and a western area, known respectively to physiographers as the Salem Plateau and the Springfield Plateau. Headward erosion by the south flowing tributaries to the White River in northern Arkansas has created a southern escarpment to both the Springfield and Salem plateaus that runs from McDonald through Barry, Stone, Christian, Douglas, and Howell counties. To the south of this escarpment lies some of the more rugged and highly dissected parts of the Missouri Ozarks. The famed Shepherd of the Hills region near Branson lies within this rugged area. To the east of the West Plains plain lies the dissected valleys of the Eleven Point River and the Current River.

Superficially, each is a simple rolling plateau, much broken by erosion (though considerable undissected areas drained by underground channels remain), especially in the east, and dotted with hills. Some of these are residual outliers of the eroded Mississippian limestones to the west, and others are the summits of a Precambrian topography above and around which sedimentary formations were deposited and then eroded. There is no arrangement in chains, but only scattered rounded peaks and short ridges, with winding valleys about them.

The two highest points in the state are Taum Sauk Mountain at 1,772 ft (540 m) in the St. Francois Mountains in Iron County and Lead Hill just east of the community of Cedar Gap at 1,744 ft (532 m) in the southwestern corner of Wright County. Few localities have an elevation exceeding 1,400 ft (430 m). Rather broad, smooth valleys, well degraded hills with rounded summits, and despite the escarpments generally smooth contours and sky-lines, characterize the bulk of the Ozark region.

Mississippi Alluvial Plain

The third region, the lowlands of the south-east and part of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain, has an area of some 3,000-square-mile (7,800 km2). It is an undulating country, for the most part well drained, but swampy in its lowest portions. The Mississippi is skirted with lagoons, lakes and morasses from Ste. Genevieve to the Arkansas border, and in places is confined by levees. These lowlands are the northernmost extent of the Mississippi embayment. The area is within the New Madrid Seismic Zone and includes the epicenter location of the 1811–12 New Madrid earthquakes at New Madrid, Missouri.

Climate

Missouri generally has a humid continental climate with cool, sometimes cold, winters and hot, humid, and wet summers. In the southern part of the state, particularly in the Bootheel, the climate becomes humid subtropical. Located in the interior United States, Missouri often experiences extreme temperatures. Without high mountains or oceans nearby to moderate temperature, its climate is alternately influenced by air from the cold Arctic and the hot and humid Gulf of Mexico. Missouri's highest recorded temperature is 118 °F (48 °C) at Warsaw and Union on July 14, 1954, while the lowest recorded temperature is −40 °F (−40 °C) also at Warsaw on February 13, 1905.

Located in Tornado Alley, Missouri also receives extreme weather in the form of severe thunderstorms and tornadoes. On May 22, 2011, a massive EF-5 tornado killed 158 people and destroyed roughly one-third of the city of Joplin. The tornado caused an estimated $1–3 billion in damages, killed 159 people and injured more than a thousand. It was the first EF5 to hit the state since 1957 and the deadliest in the U.S. since 1947, making it the seventh deadliest tornado in American history and 27th deadliest in the world. St. Louis and its suburbs also have a history of experiencing particularly severe tornadoes, the most recent one of note being an EF4 that damaged Lambert-St. Louis International Airport on April 22, 2011. One of the worst tornadoes in American history struck St. Louis on May 27, 1896, killing at least 255 people and causing $10 million in damage (equivalent to $3.9 billion in 2009 or $5.32 billion in today's dollars).

| Monthly normal high and low temperatures for various Missouri cities in °F (°C). | |||||||||||||||

| City | Avg. | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia | High | 37 (3) |

44 (7) |

55 (13) |

66 (19) |

75 (24) |

84 (29) |

89 (32) |

87 (31) |

79 (26) |

68 (20) |

53 (12) |

42 (6) |

65.0 (18.3) |

|

| Columbia | Low | 18 (−8) |

23 (−5) |

33 (1) |

43 (6) |

53 (12) |

62 (17) |

66 (19) |

64 (18) |

55 (13) |

44 (7) |

33 (1) |

22 (−6) |

43.0 (6.1) |

|

| Kansas City | High | 36 (2) |

43 (6) |

54 (12) |

65 (18) |

75 (24) |

84 (29) |

89 (32) |

87 (31) |

79 (26) |

68 (20) |

52 (11) |

40 (4) |

64.4 (18.0) |

|

| Kansas City | Low | 18 (−8) |

23 (−5) |

33 (1) |

44 (7) |

54 (12) |

63 (17) |

68 (20) |

66 (19) |

57 (14) |

46 (8) |

33 (1) |

22 (−6) |

44.0 (6.7) |

|

| Springfield | High | 42 (6) |

48 (9) |

58 (14) |

68 (20) |

76 (24) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

90 (32) |

81 (27) |

71 (22) |

56 (13) |

46 (8) |

67.6 (19.8) |

|

| Springfield | Low | 22 (−6) |

26 (−3) |

35 (2) |

44 (7) |

53 (12) |

62 (17) |

67 (19) |

66 (19) |

57 (14) |

46 (8) |

35 (2) |

26 (−3) |

45.0 (7.2) |

|

| St. Louis | High | 40 (4) |

45 (7) |

56 (13) |

67 (19) |

76 (24) |

85 (29) |

89 (32) |

88 (31) |

80 (27) |

69 (21) |

56 (13) |

43 (6) |

66.2 (19.0) |

|

| St. Louis | Low | 24 (−4) |

28 (−2) |

37 (3) |

47 (8) |

57 (14) |

67 (19) |

71 (22) |

69 (21) |

61 (16) |

49 (9) |

38 (3) |

27 (−3) |

48.0 (8.9) |

|

| Source:[1] | |||||||||||||||

.jpg.webp)

Drainage

The drainage of the state is wholly into the Mississippi River, directly or indirectly, and to a large extent into either that river or the Missouri River within the borders of the state. The latter stream, crossing the state and cutting the eastern and western borders at or near St Louis and Kansas City respectively, has a length within Missouri of 430 miles (690 km). The areas drained into the Mississippi outside the state through the St. Francis, White and other minor streams are relatively small. The larger streams of the Ozark dome are of decided interest to the physiographer. Those of the White system have open trough valleys bordered by hills in their upper courses and canyons in their lower courses.

Both the Ozark region and the northern plain region are divided by minor escarpments into ten or twelve sub-regions. There are remarkable differences in the drainage areas of their two sides, with interesting illustrations of shifting water-partings; and the White, Gasconade, Osage and other rivers are remarkable for upland meanders, lying, not on flood-plains, but around the spurs of a highland country. These incised meanders have been interpreted to have formed by downward erosion after uplift of an older peneplain surface.

Many streams in Missouri are called "rivers" though they are small enough perhaps to be called "creeks". This is due to a direct translation of the French word "rivière" which implies a stream size smaller than the French word "fleuve", meaning "a river that flows to the sea". An example of this is "Loutre River", from "Rivière Loutre", or "Otter Stream".

Caves

The Ozarks region has a well-developed karst topography with numerous areas of sinkholes, stream capture, and cavern development.

Caves, within areas of limestone and dolomite bedrock, occur in great numbers in and near the Ozark Mountain region in the southwestern part of Missouri. More than a hundred have been discovered in Stone County alone, and there are many in Christian, Greene and McDonald counties.

Marvel Cave is located a short distance southeast of the center of Stone county. The entrance originally was through a large sink-hole at the top of Roark Mountain, though now an easier entrance has been made. Marvel Cave has a large hall-like room about 350 ft (110 m) long and about 125 ft (38 m) wide with bluish-grey limestone walls, and a vaulted roof, rising from 100 to 295 ft (90 m). Due to its acoustic properties the room has been named the Auditorium. At one end is a large stalagmite formation about 65 ft (20 m) in height and about 200 ft (61 m) in girth, called the White Throne.

Exploration of Jacobs Cavern, near Pineville, McDonald county, revealed human and animal skeletons along with crude implements. Crystal Cave, near Joplin, Jasper county, has its entire surface lined with calcite crystals and scalenohedron formations, from 1 to 2 ft (0.61 m) in length.

Other caves include Friede's Cave, about six miles (10 km) northeast of Rolla, Phelps County and Mark Twain Cave (in Marion County, about one mile (1.6 km) south of Hannibal), which has a deep pool containing many eyeless fish.

See also

References

- ↑ "Missouri Weather And Climate". Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- Guccione, M., 1983, Quaternary sediments and their weathering history in north central Missouri. Boreas. vol. 12, pp. 217–226.

- Rovey, C.W., IIa and W.F. Keanb, 1996, Pre-Illinoian Glacial Stratigraphy in North-Central Missouri. Quaternary Research. vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 17–29

- Unklesbay, A.G; & Vineyard, Jerry D. (1992). Missouri Geology—Three Billion Years of Volcanoes, Seas, Sediments, and Erosion. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-0836-3

- Bretz, J Harlen. Caves of Missouri. 2012 reprint: J. Missouri. ISBN 978-0-988668-50-8

External links

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Missouri". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 607–614. (See p. 608.)