.jpg.webp)

George Case (1747–1836) was a British slave trader who was responsible for at least 109 slave voyages. Case was the co-owner of the slave ship Zong, whose crew perpetrated the Zong massacre. After the massacre, the ship owners went to court in an attempt to secure an insurance payout of £30 for each enslaved person murdered. A public outcry ensued and strengthened the abolition movement in the United Kingdom. In 1781, he became Mayor of Liverpool. After he died, the wealth generated by his slavery was bequeathed to the Case Fund by his grandson.

Slave trade

%252C_plate_IV_-_BL.jpg.webp)

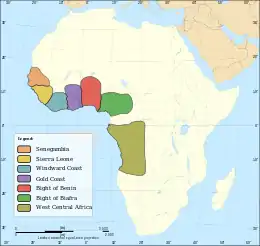

George Case was one of Britain's most prolific slave traders.[1] Case's slave ships typically followed the triangular transatlantic slave trade route. On the first leg of the route the ships took goods to Africa to be sold and exchanged for enslaved people. On the second leg the enslaved people were shipped to the Americas or Caribbean where they were sold. On the third leg sugar, cotton and other goods were returned to Britain.[2] He was responsible for at least 109 slave voyages, taking over 40 per cent of his slaves from the Bight of Biafra which today is located in the Gulf of Guinea.[3] Over 40 per cent of the enslaved people he transported were delivered to Jamaica in the Caribbean, which was a British Colony. Many of the enslaved people were forced to work in plantations producing sugar or cotton, with some forced into domestic servitude.[4]

In 1780, Case entered a syndicate with a number of other slavers. The syndicate sent a slave ship called the William on five slave voyages before it was shipwrecked on its sixth voyage in 1787.[5] In 1798, Case sent one of his ships called Molly and captained by John Tobin to Angola, where he purchased 436 enslaved people.[6]

Slave life

Just under half of Case's enslaved people were sold in Jamaica. The Diary of Thomas Thistlewood is an important historical document detailing how they were treated after they were sold in 18th-century Jamaica. Thomas Thistlewood (16 March 1721 ‒ 30 November 1786) was an overseer and plantation owner on the island who kept meticulous records of his behaviour. Thistlewood routinely beat his forced labourers, raped the women and invented a form of torture called Derby's dose.[7]

Zong massacre

Case was the co-owner of a slave ship called the Zong, along with William Gregson.[8] When drinking water on the Zong ran low the crew murdered 142[lower-alpha 1] enslaved people by throwing them into the sea. The ship owners then made an insurance claim for those murdered. The insurance company refused to pay out, and the resulting court case brought the murders to a wide public audience.[9] In the original case the court found in favour of the slavers and the insurance company was ordered to pay out compensation. The judge, Lord Mansfield, insisted that the "Case of Slaves was the same as if Horses had been thrown overboard".[8] The outcome led to a national outcry that stimulated the abolitionist movement in the UK.[10]

Case and Gregson demanded to be paid £30 for each 'lost' enslaved persons. Abolitionists Olaudah Equiano and Granville Sharp launched a campaign and ordered solicitors to begin court action "against all persons concerned in throwing into the sea 133 slaves".[9] The court cases re-affirmed the right of slavers to murder their victims, however, they are credited with being a legal landmark, because they strengthened public opinion in favour of abolition.[11]

The Slave Ship

The Zong massacre is believed to have inspired J. M. W. Turner to paint The Slave Ship in 1840. Turner was an acclaimed English painter of landscapes who was also an abolitionist. The painting depicts a slave ship in a storm with dark skinned people in manacles in the water. The painting is owned by and on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, in Boston, United States of America.[12]

Personal life

Case married the daughter of William Gregson, the leading partner in the Zong massacre.[5] He owned a country house called Walton Priory, that is now demolished.[13] Case was one of the founders and the first president of the Liverpool Athenaeum.[14]

He died at Walton Priory and was buried in Prescot Parish Church where there is a fine monumental brass designed by A. W. N. Pugin[15][16] in his memory.

Mayor of Liverpool

In 1833, Case became the treasurer of Liverpool Council.[14] He chaired the finance committee of Liverpool Council for 38 years from 1775.[1] In 1781-1782 he was Mayor of Liverpool.[17] Liverpool was Britain's pre-eminent slave trading city and at least twenty-five Mayors of Liverpool were slave traders.[18] In 1787, the Liverpool Council became concerned with the growth of the abolition movement and they petitioned Parliament against the regulation of the slave trade. In 1788, the Liverpool Council stated to Parliament "that the trade had been legally and uninterruptedly carried on for centuries past by many of [H]is Majesty's subjects, with advantages to the country, both important and extensive; but had lately been unjustly reprobated as impolitic and inhuman."[19] A portrait of Case by Thomas Phillips is part of the Walker Art Gallery collection in Liverpool. The painting shows Case in his robes as mayor.[20]

The Case Fund

Case's wealth was passed to his son, John Dean Case, and then in 1898 was bequeathed by his grandson, George Case, an Anglican and Roman Catholic clergyman to the Hibbert Trust. The Hibbert Trust call the bequeathed money the Case Fund. The fund "seeks to promote liberal religion more generally and upholds the unfettered exercise of private judgement in matters of religion."[14]

In 2020, in response to the Black Lives Matter movement the trust set up an investigation to determine how to proceed. The trust stated that in 2020 less than half of the Case Fund's assets were derived from Case's slavery and it is not possible to give a more accurate figure.[14] The trust wrote "The Trustees acknowledge that people of colour have been victimised by white privilege for over 400 years", pledging to find ways of making reparations.[14]

References

- 1 2 "Catalyst Reviews - Liverpool 800 - Culture, Character and History". www.catalystmedia.org.uk.

- ↑ "The National Archives".

- ↑ Richardson 2007, p. 28.

- ↑ Richardson 2007, p. 29.

- 1 2 Dalton 2021, p. 3-4.

- ↑ "The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire" (PDF). www.hslc.org.uk.

- ↑ Hall 1999, p. 73.

- 1 2 Rupprecht, Anita (2007). "Excessive Memories: Slavery, Insurance and Resistance". History Workshop Journal (64): 7. JSTOR 25472933 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 "The National Great Blacks in the Wax Museum" (PDF).

- ↑ Rupprecht, Anita (2007). "Excessive Memories: Slavery, Insurance and Resistance". History Workshop Journal (64): 14. JSTOR 25472933 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ "How an insurance lawsuit helped end the slave trade". Fortune.

- ↑ "Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On)". collections.mfa.org.

- ↑ "Historic England".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Trust, Hibbert (31 May 2021). "History of the Trusts". The Hibbert Trust.

- ↑ Pollard, Richard; Nikolaus Pevsner (2006), Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West, The Buildings of England, New Haven & London: Yale University Press, pp. 540–542, ISBN 0-300-10910-5

- ↑ Whitham, Janet (January 2010). "Lancashire" (PDF). Monumental Brass Society Bulletin (113): 252–254. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ↑ "Former Mayors and Lord Mayors". Liverpool Town Hall.

- ↑ Long, Chris (15 January 2020). "The slavers and abolitionists on Liverpool's streets". BBC News.

- ↑ Williams 1897, p. 611.

- ↑ "Portrait of George Case".

Notes

- ↑ The number of slaves recorded as murdered varies.

Sources

- Richardson, David (2007). Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery. UK: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-066-9.

- Dalton, Carolyn (2021). "Memorial to Zong: The Gregson Syndicate – The Crew – The Abolitionists" (PDF). Lancaster City Museums.

- Hall, Douglas (1999). In miserable slavery : Thomas Thistlewood in Jamaica, 1750-86. Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press. ISBN 978-1-4356-9488-0. OCLC 302368014.

- Williams, Gomer (1897). History of the Liverpool Privateers. UK: Liverpool University Press.