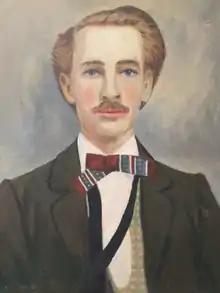

Major George Wayne Anderson Jr | |

|---|---|

George Wayne Anderson | |

| Born | August 5, 1839 Savannah, Georgia |

| Died | August 10, 1906 (aged 67) Savannah, Georgia |

| Place of burial | Laurel Grove Cemetery, Savannah, Georgia |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 (CSA) |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | 1st Georgia Volunteer Infantry Co C, The Savannah Republican Blues Chatham Artillery Fort McAllister |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Major George Wayne Anderson Jr, (August 5, 1839 – August 10, 1906) was an officer in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He commanded the Republican Blues and later Fort McAllister near Savannah, Georgia before its capture in 1864.

Early life and military career

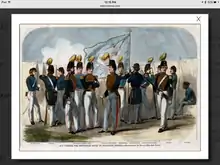

Anderson attended the University of Virginia 1856–1859. He enlisted in the Georgia 2nd Infantry Company (Republican Blues) on 31 May 1861, as a second lieutenant. The Blues were a military company formed in Savannah in 1806, and served during the War of 1812 in Florida. Unlike most Confederate units formed during the Civil War, the Republican Blues had been an existing militia organization for over fifty years before the war started. They recruited from the most prominent families in and around Savannah. The Blues visited New York City in 1860, hosted by their counterparts in the city. There was much goodwill expressed during the visit, as reported in the New York Times.

They fought in all the nation's wars after The Civil War as part of the Georgia National Guard, except for the Spanish–American War. Anderson was promoted to command the Blues after his uncle, John Wayne Anderson, retired in 1862. The Blues served under the U.S. flag before taking up arms against it, and after the war they continued their existence in the National Guard of the reunited nation.[1]

Civil War

Anderson and the Blues were assigned to Fort McAllister in 1862[2] to bolster its defenses. This reunited him with his older brother, Colonel Robert H. Anderson, who was leading Fort McAllister's garrison before a promotion would send him to lead the 5th Georgia Cavalry in support of General Joseph Wheeler.[3] George Wayne Anderson was placed in command of the fort following the death of Major John B. Gallie on February 1, 1863.[4]

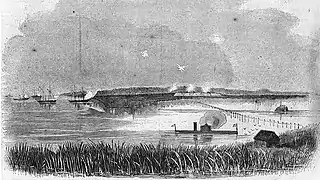

McAllister was one of three forts protecting Savannah, the others being Fort Pulaski and Fort James Jackson standing in Confederate defiance of the Union naval blockade. The southeast coast of the United States was the place where both combatants tested the latest in naval artillery and coastal defenses.[5] Fort McAllister was the key to unlocking the defenses around Savannah, one of the most important Confederate ports on the Atlantic Ocean. The battles to come would prove to be pivotal in the war, with President Abraham Lincoln winning reelection as one result.

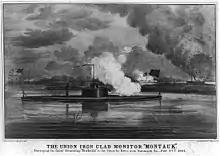

Union Navy Commander John Lorimer Worden, who commanded USS Monitor against CSS Virginia in March, was placed in command of the new ironclad USS Montauk and was ordered to ready an attack on Fort McAllister.[6] Taking advantage of the opportunity to test the new 15-inch (380 mm) Dahlgren gun and the armor of the Passaic-class ironclad for the first time, on 27 January Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont sent Montauk, along with the gunboats Seneca, Wissahickon, Dawn and the mortar schooner C. P. Williams to bombard the Fort.

The Union was hoping that the new armament and projectiles would have as much success there as they had achieved earlier at Fort Pulaski. The new guns had reduced that fort to ruins within hours, the garrison surrendering under the incessant pounding. At Fort McAllister, after seven hours of fire from the monitors during the day, and from the mortar boats through the night, the attack resulted in only minor damage. Only three men were wounded, but all felt the loss of the fort's mascot, Tom Cat. He died during the shelling, and today there is a marker in his honor inside the fort.[7]

The design of Fort McAllister proved to be surprisingly resilient, absorbing most of the impact from the shells and was quickly repaired overnight. Neither the heavy guns nor the ironclad ships were able to destroy the fort because it was earthwork, not made of bricks and stone. Imagine how disheartening it would be to fire on the fort all day, only to see it reappear seeming undamaged overnight.[8] After seven unsuccessful engagements over the next year, the US Navy retired to Ossabaw Sound to await the coming of General William Tecumseh Sherman, now on the march and destroying Georgia.

Sherman approaches

Anderson made the decision to defend the fort after not receiving orders or telegraph communications from General William J. Hardee regarding how he should react to the threat approaching.[9] General Sherman believed that the outcome of the entire campaign rested on capturing Fort McAllister, opening his way to the sea.[10] To lead the attack, Sherman assigned his best, his old 2nd Division that he led at Shiloh, now commanded by General William Babcock Hazen.[11]

You will have to capture that fort

_(14576243590).jpg.webp)

General Sherman and his staff, along with the Signal Corps, observed the attack from Cheve's Rice Mill, about 3 miles from the fort. As they stood on the roof of the mill, nervously awaiting the assault to begin, a staff member remarked "George Anderson is in command, General, the flag will never be lowered. You will have to capture that fort."[12] He knew Anderson from boyhood, and that he would not surrender, even with his forces outnumbered 25 to 1.

Fort McAllister proved not only to be resilient, but its fall gave birth to some of the kindness and compassion that would ease reconciliation. After Union forces under General Hazen's 2nd Division attacked, the 47th and 70th Ohio, 90th and 111th Illinois overwhelmed the defenders. Attacking from all sides, as well as along the riverbank, the fight was over quickly. The battle ended after Confederate Captain Nicholas B. Clinch, engaged in ferocious hand-to-hand combat, was overwhelmed and subdued.[13]

General Hazen was one of the first Union soldiers inside the fort, where he spotted both Clinch and Major Anderson in the thick of the fight. Having attended the US Military Academy at West Point with Anderson's older brother, General Robert H. Anderson, Hazen was familiar with both the Anderson and Clinch families in Savannah. Seeing the stunned and bleeding commander sitting on a wooden crate, Hazen spoke to him, "Major Anderson, my apologies for your rough treatment." Anderson looked up at him and said "It's war, General. My men gave it their best, I assure you. These men were not prepared to give you anything".[14] Hazen could see across the marsh to the rice mill where General Sherman watched and waited,[15] anxious for a signal that the fort was theirs. Looking back to Anderson he spoke, "Get to the rear, George, and report to me later.".[16] Fort McAllister is where Sherman's March to the Sea ended,[17] and where the war ended for Major Anderson.

Reconciliation begins

"The fort never surrendered, it was captured by overwhelming force", recalled Anderson.[18] General Hazen agreed with Anderson's accounting of the battle, reporting that his forces fought "the garrison through the fort to their bomb-proofs, from which they still fought, and only succumbed as each man was individually overpowered."[19] Before being confined, Anderson observed a company of Union soldiers marching out of the fort, on a course that would lead them into some buried ordinance that would have detonated under their feet.[20] Taking their hand, Anderson led them out of harms way. This story was fondly remembered years later in a letter from the once-young lieutenant George W. Sylvis of the 47th Ohio, when he wrote to his old adversary.[21] The old wounds were beginning to heal.

With McAllister captured, General Sherman's forces were able to link up with the Union Navy delivering much-needed supplies and clearing the way to Savannah. The Confederate leadership realized the hopelessness of the situation following McAllister's capture and withdrew their remaining forces into South Carolina. In a telegram dated December 22, 1864, General Sherman presented the city of Savannah as a Christmas gift to President Lincoln.

During the evening that the fort fell, Anderson was being held at the Anderson family home, Lebanon plantation the new headquarters of General Hazen. General Hazen and Lt. Col. Strong invited General Sherman to dinner, to celebrate their victory. In a kind gesture of respect, General Hazen also invited Major Anderson to attend the meal, after clearing the request with Sherman.[22] The discussion was surely lively - during the meal Anderson engaged in a heated exchange with General Sherman about the tactics employed to defend the fort[23] and the bravery of all who fought there. Cigars were exchanged and smoked, tributes were made to the fallen.[24]

Major Anderson was sent to Hilton Head, SC; Point Lookout, MD; then on to the Old Capitol Prison, in Washington DC. He was later transferred to Fort Delaware before taking the oath of alliegance on June 4, 1865, being released under the orders of General Ulysses Grant.[25] Anderson then returned to Savannah and his home, Lebanon plantation, just up the road from Fort McAllister.

Postbellum career

Anderson worked for the W W Gordon company in Savannah after the war, entertaining many with stories of both the war and that 'old rascal', General Sherman.[26] His older brother, Robert H. Anderson was appointed by two post-Civil War Presidents to serve on the Board of Visitors at West Point, while Police Chief of Savannah for over 20 years. George Wayne Anderson died in Savannah in 1906, and is buried near his friend Major Gallie at Laurel Grove Cemetery.

State of Georgia Resolution Commending Captain Anderson in the defense of Fort McAllister

Excerpted from the resolution honoring both Anderson and the garrison under his command.

Resolved, that Capt. George W Anderson, Jr., who succeeded Major Gallie in command of that post, for the cool courage and successful defense of Fort McAllister, and the noble band under the wise orders of this youthful Commander, deserve the kind remembrance and grateful feelings of the people of the state.

Gallery

USS Montauk Attacks Fort McAllister

USS Montauk Attacks Fort McAllister_at_Fort_McAllister%252C_GA%252C_US.jpg.webp) Columbiad cannon (1964 reproduction) at Fort McAllister, GA, US

Columbiad cannon (1964 reproduction) at Fort McAllister, GA, US Fort McAllister in 2014

Fort McAllister in 2014 Fort McAllister in 2014

Fort McAllister in 2014 Fort McAllister in 2014

Fort McAllister in 2014 Fort McAllister in 2014

Fort McAllister in 2014 Fort McAllister in 2014

Fort McAllister in 2014 Fort McAllister in 2014

Fort McAllister in 2014 Fort McAllister in 2014

Fort McAllister in 2014 Fort McAllister in 2014

Fort McAllister in 2014 Fort McAllister in 2014

Fort McAllister in 2014 Fort McAllister in 2014

Fort McAllister in 2014 George Wayne Anderson Jr Gravesite at Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah, GA

George Wayne Anderson Jr Gravesite at Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah, GA George Wayne Anderson Jr Gravesite at Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah, GA

George Wayne Anderson Jr Gravesite at Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah, GA George Wayne Anderson Jr Gravesite at Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah, GA

George Wayne Anderson Jr Gravesite at Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah, GA Main House at Lebanon Plantation in Savannah, GA

Main House at Lebanon Plantation in Savannah, GA

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Dixon, p. 1

- ↑ Christman, p. 16

- ↑ Smith, p. 104

- ↑ Durham, p. 106

- ↑ Durham, p. 102

- ↑ Durham, p. 37

- ↑ Smith, p. 37

- ↑ Schiller, p. 31

- ↑ Smith, p. 176

- ↑ Shaara, p. 246

- ↑ Foote, p. 651

- ↑ Livingston, p. 98

- ↑ Trudeau, p. 437

- ↑ Shaara, p. 261

- ↑ Sherman, p. 674

- ↑ Trudeau, p. 438

- ↑ Christman, p. 76

- ↑ Smith, p. 178

- ↑ Christman, p. 70

- ↑ Trudeau, p. 439

- ↑ Durham, p. 165

- ↑ Shaara, p. 265

- ↑ Durham, p. 169

- ↑ Smith, p. 179

- ↑ Livingston, p. 124

- ↑ Durham, p. 169

Sources

- Livingston, Gary, Among the Best Men the South Could Boast - The Fall of Fort McAllister, Caisson Press, 1997, Library of Congress Catalog 96-92895

- Sherman, William Tecumseh, Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman, Penguin Putnam The Library of America, 1990, ISBN 0-940450-65-8

- Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, a narrative - Vol III - Red River to Appomattox, Vintage Books - Random House, 1986, ISBN 978-0-3947-4622-7

- Christman, William E., UNDAUNTED: The History of Fort McAllister, Georgia, Darien Printing & Graphics, 1996, Library of Congress Catalog 96-77666 ASIN: B002DHN66S

- Smith, Derek, Sumter - After The First Shots, Stackpole Books, 2015, ISBN 978-0-8117-1614-7

- Smith, Derek, Civil War Savannah, Frederic C. Beil, 1997, ISBN 978-1-9294-9000-4

- Shaara, Jeff, The Fateful Lightning, Ballatine Books, 2015, ISBN 978-0-3455-4919-8

- Dixon, William Daniel and Durham, Roger S, The Blues in Gray - The Civil War Journal of William Daniel Dixon and the Republican Blues Daybook, University of Tennessee Press, 2000, ISBN 978-1-5723-3101-3

- Durham, Roger S., Guardian of Savannah - Fort McAllister, Georgia, in the Civil War and Beyond, The University of South Carolina Press, 2008, ISBN 978-1-5700-3742-9

- Trudeau, Noah Andre, Southern Storm - Sherman's March to the Sea, HarperCollins, 2009, ISBN 978-0-0605-9868-6

- Schiller, Herbert M., Fort Pulaski and the defense of Savannah - Civil War Series, Eastern National, 1997

External links

- https://uvastudents.wordpress.com/2014/02/14/george-wayne-anderson-jr-5-aug-1839-10-aug-1906 - Retrieved 3 Mar 2016

- http://gastateparks.org/FortMcAllister/ Fort McAllister State Park - Retrieved 21 Mar 2016

- https://archive.org/stream/rulesregulations00geor#page/12/mode/2up - Retrieved 10 April 2016