George Whitney Calhoun | |

|---|---|

circa 1950s | |

| Born | September 16, 1890 Green Bay, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Died | December 6, 1963 (aged 73) Green Bay, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | Founding the Green Bay Packers |

George Whitney Calhoun (September 16, 1890 – December 6, 1963) was an American newspaper editor and co-founder of the Green Bay Packers, a professional American football team based in Green Bay, Wisconsin. After establishing the Packers in 1919 with Curly Lambeau, Calhoun served the team in various capacities for 44 years until his death in 1963. Utilizing his editorial job at the Green Bay Press-Gazette, he became the team's first publicity director, helping to establish local support and interest. He also served as the first team manager and was a member of the board of directors of the non-profit corporation that owns the team. Although often overshadowed by the more famous Curly Lambeau, Calhoun was instrumental to the early success of the Packers. In recognition of his contributions, Calhoun was elected to the Green Bay Packers Hall of Fame in 1978.

Personal life

George Whitney Calhoun was born in Green Bay, Wisconsin on September 16, 1890, the son of Walter A. Calhoun and Emmeline Whitney Calhoun. The Calhoun family was well known in the area: Walter was employed at the Green Bay Water Company and Emmeline was the granddaughter of Daniel Whitney, one of the founders of Green Bay.[1] Calhoun and his family moved to Buffalo, New York, where they lived until 1915. While in New York, Calhoun attended the University at Buffalo where he played hockey and football.[2] While being tackled during a collegiate football game, he crashed into a goalpost, which left him temporarily paralyzed and permanently unable to play competitive sports.[3] Calhoun recovered and completed his studies in 1913. Before moving back to Green Bay in 1915, he started working in the newspaper industry for the Buffalo Times, where he stayed for two years.[1]

In 1915, Calhoun was hired by the Green Bay Review as a telegraph editor,[note 1] where he worked for two years. He then joined the Green Bay Press-Gazette, also as a telegraph editor, a job he held for 40 years until his retirement in 1957.[2] While working for the Press-Gazette, Calhoun helped form hockey, baseball, and football teams across the region.[5] He also became a well-known sportswriter who was respected by his peers for his knowledge of the Green Bay Packers and the early history of the National Football League (NFL).[6] Calhoun died on December 6, 1963, in Green Bay, six years after retiring from the Press-Gazette.[3][7]

Green Bay Packers

Professional football began in Green Bay in 1919, although various city teams had been organized for years. During a chance encounter, Calhoun raised the idea of starting a football team with Curly Lambeau. Calhoun was familiar with Lambeau's sports experience at Green Bay East High School and maintained a friendship with him while Lambeau was at the University of Notre Dame to play football.[1] Their encounter occurred after Lambeau had dropped out of Notre Dame due to illness.[8] Lambeau still wanted to play football, so Calhoun recommended they start a football team together. Lambeau persuaded his employer the Indian Packing Company to sponsor the team and pay for its uniforms and equipment.[1] Calhoun, using his job at the Press-Gazette,[9] wrote a few articles inviting potential football players to attend a meeting to discuss the formation of a local football team.[10] The Green Bay Packers were officially organized on August 11, 1919, in the Press-Gazette office.[11] A second meeting three days later on August 14 attracted up to 25 people interested in playing for the newly formed team.[5]

After two years of playing teams around Wisconsin, the Packers entered the American Professional Football Association, the precursor to the modern-day NFL.[note 2] Calhoun became the team's publicity director and traveling manager, helping to organize games and promote the new franchise.[13] Because the Packers played in such a small market, they relied heavily on the revenue from away games, which was generated by Calhoun's efforts promoting the team.[5] He also helped raise funding for the Packers during periods of financial difficulty.[14] Before the Packers charged for admission, he organized cash collections during games to raise additional funds.[15] After the Packers erected a fence, Calhoun manned the front gates and ensured game attendees paid to enter the grounds.[1]

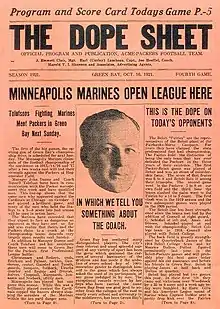

Calhoun wrote The Dope Sheet, the Packers' official newsletter and game program from 1921 to 1924. Because of the constant changing of teams and players in the NFL during the 1920s, The Dope Sheet was important in keeping fans up-to-date on the Packers and their opponents.[6] Calhoun used his job at the Press-Gazette to network with other sports editors and maintain a vast database of early NFL game summaries and statistics. His love of beer and his unique networking abilities were so well known that Calhoun's hotel room was a popular venue before and after Packers games.[1][5]

Calhoun continued in his role as publicity director until 1947, when he was forced to resign by Lambeau.[1] This was unpopular and permanently damaged Calhoun's relationship with Lambeau.[16] Even after leaving the team, Calhoun remained a strong supporter of the Packers and attended every home game from 1919 to 1956. He also served on the Board of Directors of Green Bay Packers, Inc. until his death.[1][3]

Legacy

Calhoun's legacy is complicated and often overlooked when compared to his counterpart, Curly Lambeau.[17] Lambeau served as both a player (for ten years) and the head coach, a role he had for 30 years from 1919 to 1949. The prominence of these roles and the early success of the Packers helped enshrine Lambeau in the Pro Football Hall of Fame[18] and led to the Packers naming their current stadium after him.[19] Calhoun never received these same honors, although his contributions were significant.[1] Calhoun's penchant for publicizing the team, his ability to raise funds, and his role as team manager were essential to the Packers surviving as a franchise and succeeding on the field.[1] He is attributed with developing the name "Packers"[note 3] and his Dope Sheet was an important tool to keep fans informed of game results, statistics, and players.[1][6]

The Packers have recognized Calhoun's influence and contributions in many ways. After Calhoun's death in December 1963, his ashes were scattered on the field at City Stadium.[1] In 1978, Calhoun was elected to the Green Bay Packers Hall of Fame in recognition of his status as a founder of the team, publicist, and board member.[21] In 2013, a bronze sculpture of Calhoun was dedicated as part of the Packers Heritage Trail plaza in downtown Green Bay.[22] Decades after its last publication, the Packers revived the title The Dope Sheet for its modern-day game program to honor Calhoun's early contributions to the team.[23]

Notes

- ↑ The word telegraph refers to electrical telegraph, the transmission of electronic messages. After the development of the technology in the 1830s, newspapers used telegraphy to distribute news stories across the country.[4]

- ↑ The league was called the American Professional Football Association for two years before being renamed in 1921 to the National Football League.[12]

- ↑ Some sources defer on the attribution of the name Packers, although they agree it was based on the Indian Packing Company, and later the Acme Packing Company. Some sources attribute the name to Curly Lambeau's girlfriend, and not Calhoun.[20] Calhoun had used various names to describe the team in the beginning, including the Bays, the Indians and the Packers.[13] Regardless of the source, the name stuck after Calhoun's printing and publicity of the name Packers.[1][3]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Hendricks, Martin (October 2, 2008). "A founding figure behind the scenes". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- 1 2 "One of Packer Founders Dies". The Daily Telegram. December 7, 1963. p. 11. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 "Packers' Co-Founder, George Calhoun, Dies at 73 in Green Bay (part 1)". The Post-Crescent. December 6, 1963. p. B7. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "America's original wire: The telegraph at 150". CBS Interactive Inc. Associated Press. October 24, 2011. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Dougherty, Pete (August 21, 2018). "Dougherty: Fledgling Packers needed unlikely lifeline to survive, soar". Green Bay Press-Gazette. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Povletich 2012, p. 10.

- ↑ "Packers' Co-Founder, George Calhoun, Dies at 73 in Green Bay (part 2)". The Post-Crescent. December 6, 1963. p. B8. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved August 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Povletich 2012, p. 4.

- ↑ Christl, Cliff (March 26, 2016). "The Truth and Myth About the Hungry Five". Green Bay Packers, Inc. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ↑ Povletich 2012, p. 5.

- ↑ Christl, Cliff (August 11, 2016). "High Five: Biggest myths about Packers birthday". Green Bay Packers, Inc. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ↑ "1922 American Professional Football Association changes name to National Football League". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on August 6, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- 1 2 Povletich 2012, p. 6.

- ↑ Srubas, Paul (October 12, 2017). "Too lazy to walk the Packers Heritage Trail? Read this". Green Bay Press-Gazette. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ↑ Christl, Cliff (July 27, 2017). "The Greatest Story in Sports". Green Bay Packers, Inc. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ↑ Povletich 2012, p. 67.

- ↑ Dougherty, Pete (August 8, 1993). "Sportswriter's idea spurred Lambeau". Green Bay Press-Gazette. p. 156. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - ↑ "Earl (Curly) Lambeau". Pro Football Hall of Fame. 2018. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ↑ "'Lambeau Field' voted by council". Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. August 5, 1965. p. 3-part 2. Archived from the original on 2016-05-10. Retrieved August 3, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ The Legend of Lambeau Field: The Heroes, the Highlights, the History. Frozen Tundra Films. February 23, 2010. ASIN B0000CC88W.

- ↑ "Green Bay Hall of Famers". Green Bay Packers, Inc. 2018. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Packers Heritage Trail unveils new plaza, statues". Nexstar Media Group. September 14, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ↑ "The Dope Sheet" (PDF). Green Bay Packers, Inc. October 17, 2006. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

Bibliography

- Povletich, William (2012). Green Bay Packers: Trials, Triumphs, and Tradition. Wisconsin Historical Society. ISBN 9780870206030. Retrieved August 3, 2018 – via Google Books

.

.