| |

| Category | Sans-serif |

|---|---|

| Classification | Humanist |

| Designer(s) | Eric Gill |

| Foundry | Monotype |

| Date created | 1926 |

| Date released | 1928 (Monotype) |

| Design based on | Johnston |

| Variations | Gill Kayo |

Gill Sans is a humanist sans-serif typeface designed by Eric Gill and released by the British branch of Monotype from 1928 onwards.

Gill Sans is based on Edward Johnston's 1916 "Underground Alphabet", the corporate font of London Underground. As a young artist, Gill had assisted Johnston in its early development stages. In 1926, Douglas Cleverdon, a young printer-publisher, opened a bookshop in Bristol, and Gill painted a fascia for the shop for him in sans-serif capitals. In addition, Gill sketched an alphabet for Cleverdon as a guide for him to use for future notices and announcements. By this time Gill had become a prominent stonemason, artist and creator of lettering in his own right and had begun to work on creating typeface designs.

Gill was commissioned to develop his alphabet into a full metal type family by his friend Stanley Morison, an influential Monotype executive and historian of printing. Morison hoped that it could be Monotype's competitor to a wave of German sans-serif families in a new "geometric" style, which included Erbar, Futura and Kabel, all being launched to considerable attention in Germany during the late 1920s. Gill Sans was released in 1928 by Monotype, initially as a set of titling capitals that was quickly followed by a lower-case. Gill's aim was to blend the influences of Johnston, classic serif typefaces and Roman inscriptions to create a design that looked both cleanly modern and classical at the same time. Designed before setting documents entirely in sans-serif text was common, its standard weight is noticeably bolder than most modern body text fonts.

An immediate success, the year after its release the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) chose it for all its posters, timetables and publicity material. British Railways chose Gill Sans as the basis for its standard lettering when the railway companies were nationalised in 1948. Gill Sans also soon became used on the modernist deliberately-simple covers of Penguin Books and was sold up to very large sizes, which were often used in British posters and notices of the period. Gill Sans was one of the dominant typefaces in British printing in the years after its release and remains extremely popular. It has been described as "the British Helvetica" because of its lasting popularity in British design. Gill Sans has influenced many other typefaces and helped to define a genre of sans-serif, known as the humanist style.

Monotype rapidly expanded the original regular or medium weight into a large family of styles, which it continues to sell. A basic set is included with some Microsoft software and macOS.

Characteristics

The proportions of Gill Sans stem from monumental Roman capitals in the upper case, and traditional "old-style" serif letters in the lower. This gives Gill Sans a very different style of design to geometric sans-serifs like Futura, based on simple squares and circles, or grotesque or "industrial" designs like Akzidenz-Grotesk, Helvetica and Univers influenced by nineteenth-century lettering styles.[1][2][3][4] For example, compared to grotesque sans-serifs the "C" and "a" have a much less "folded up" structure, with wider apertures.[5] The "a" and "g" in the roman or regular style are "double-storey" designs, rather than the "single-storey" forms used in handwriting and blackletter often found in grotesque and especially geometric sans-serifs.

.jpg.webp)

The upper-case of Gill Sans is partly modelled on Roman capitals like those found on Trajan's Column in Rome, with considerable variation in width. These had become a standard for inscriptional lettering in Britain at the time: Gill's teacher Edward Johnston had written that, "The Roman capitals have held the supreme place among letters for readableness and beauty. They are the best forms for the grandest and most important inscriptions."[8][9][7][6] While Gill Sans is not based on purely geometric principles to the extent of the geometric sans-serifs that had preceded it, some aspects of Gill Sans do have a geometric feel.[lower-alpha 1] The J descends below the baseline. The "O" is an almost perfect circle and the capital "M" is based on the proportions of a square with the middle strokes meeting at the centre; this was not inspired by Roman carving but is very similar to Johnston.[8][lower-alpha 2] The 'E' and 'F' are also relatively narrow.

The influence of traditional serif letters is also clear in the "two-storey" lower-case "a" and "g", unlike that of Futura, and the "t" with its curve to bottom right and slanting cut at top left, unlike Futura's which is simply formed from two straight lines.[12] The lower-case "a" also narrows strikingly towards the top of its loop, a common feature of serif designs but rarer in sans-serifs.

Following the traditional serif model the italic has different letterforms from the roman, where many sans-serifs simply slant the letters in what is called an oblique style. This is clearest in the "a", which becomes a "single storey" design similar to handwriting, and the lower-case "p", which has a calligraphic tail on the left reminiscent of italics such as those cut by William Caslon in the eighteenth century.[8][13] The italic "e" is more restrained, with a straight line on the underside of the bowl where serif fonts normally add a curve.[8][lower-alpha 3] Like most serif fonts, several weights and releases of Gill Sans use ligatures to allow its expansive letter "f" to join up with or avoid colliding with following letters.[13]

The basic letter shapes of Gill Sans do not look consistent across styles (or even in the metal type era all the sizes of the same style), especially in Extra Bold and Extra Condensed widths, while the Ultra Bold style is effectively a different design altogether and was originally marketed as such.[16] Digital-period Monotype designer Dan Rhatigan, author of an article on Gill Sans's development after Gill's death, has commented: "Gill Sans grew organically ... [it] takes a very 'asystematic' approach to type. Very characteristic of when it was designed and of when it was used."[17][18] (At this time the idea that sans-serif typefaces should form a consistent family, with glyph shapes as consistent as possible between all weights and sizes, had not fully developed: it was quite normal for families to vary as seemed appropriate for their weight until developments such as the groundbreaking release of Univers in 1957.[19])

In the light weights, the slanting cut at top left of the regular "t" is replaced with two separate strokes.[lower-alpha 4] From the bold weight upwards Gill Sans has an extremely eccentric design of "i" and "j" with the dots smaller than their parent letter's stroke.[20][21][22]

Development

Morison commissioned Gill to develop Gill Sans after they had begun to work together (often by post since Gill lived in Wales) on Gill's serif design Perpetua from 1925 onwards; they had known each other since about 1913. Morison visited Cleverdon's bookshop while in Bristol in 1927 where he saw and was impressed by Gill's fascia and alphabet.[25] Gill wrote that "it was as a consequence of seeing these letters" that Morison commissioned him to develop a sans-serif family.[26][21][27][lower-alpha 5]

In the period during and after his closest collaboration with Johnston, Gill had intermittently worked on sans-serif letter designs, including an almost sans-serif capital design in an alphabet for sign-painters in the 1910s and some capital letter signs around his home in Capel-y-ffin, Wales.[21][28][lower-alpha 6] Gill had greatly admired Johnston's work on their Underground project, which he later wrote had "redeemed the whole business of sans-serif from its nineteenth-century corruption" of extreme boldness.[8][30] Johnston apparently had not tried to turn the alphabet (as it was then called) that he had designed into a commercial typeface project.[31] He had tried to get involved in type design before starting work on Johnston Sans, but without success since the industry at the time mostly created designs in-house.[29] Morison similarly respected the design of the Underground system, one of the first and most lasting uses of a standard lettering style as corporate branding (Gill had designed a set of serif letters for WH Smith), writing that it "conferred upon [the lettering] a sanction, civic and commercial, as had not been accorded to an alphabet since the time of Charlemagne".[32]

.jpg.webp)

Morison and Gill had met with some resistance within Monotype while developing Perpetua and while Morison was an enthusiastic backer of the project, Monotype's engineering manager and type designer Frank Hinman Pierpont was deeply unconvinced, commenting that he could "see nothing in this design to recommend it and much that is objectionable".[33][34][35] (Pierpont was the creator of Monotype's previous mainstay sans-serif, a loose family now called Monotype Grotesque. It is a much less sculptured design inspired by German sans-serifs.[36]) Morison also intervened to insist that the letters "J" and "Q" be allowed to elegantly descend below the baseline, something not normal for titling typefaces which were often made to fill up the entire area of the metal type.[37] In the early days of its existence it was not always consistently simply called "Gill Sans", with other names such as "Gill Sans-serif", "Monotype Sans-Serif" (the latter two both used by Gill in some of his publications) or its order numbers (such as Series No. 231) sometimes used.[38][39]

A large amount of material about the development of Gill Sans survives in Monotype's archives and in Gill's papers. While the capitals (which were prepared first) resemble Johnston quite closely, the archives document Gill (and the drawing office team at Monotype's works in Salfords Surrey, who developed a final precise design and spacing) grappling with the challenge of creating a viable humanist sans-serif lower-case as well as an italic, which Johnston's design did not have.[18][lower-alpha 7] Gill's first draft proposed many slanting cuts on the ends of ascenders and descenders, looking less like Johnston than the released version did, and quite long descenders.[42][43][44]

Early art for the italic also looked very different, with less of a slope, again very long descenders and swash capitals.[8][13][18][lower-alpha 8] The final version did not use the calligraphic italic "g" Gill preferred in his serif designs Perpetua and Joanna (and considered in the draft italic art),[44] instead using a standard "double-storey" "g".[8][45]

In the regular or roman style of Gill Sans, some letters were simplified from Johnston, with diamond dots becoming round (rectangles in the later light weight) and the lower-case "L" becoming a simple line, but the "a" became more complex with a curving tail in most versions and sizes.[18][46] In addition, the design was simply refined in general, for example by making the horizontals slightly narrower than verticals so that they do not appear unbalanced, a standard technique in font design which Johnston had not used.[8][31] The "R" with its widely splayed leg is Gill's preferred design, unlike that of Johnston; historian James Mosley has suggested that this may be inspired by an Italian Renaissance carving in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.[11][47]

Particular areas of thought during the design process were the "a" (several versions and sizes in the hot metal era had a straight tail like Johnston's or a mildly curving tail) and the "b", "d", "p" and "q", where some versions (and sizes, since the same weight would not be identical at every size) had stroke ends visible and others did not.[16][18][20][lower-alpha 9] Rhatigan has commented that Monotype's archives contain "enough [material] for a book just about the 'b', 'd', 'p', and 'q' of Gill Sans".[18][49]

The titling capitals of Gill Sans were first unveiled at a printing conference in 1928; it was also shown in a specimen issued in the Fleuron magazine edited by Morison.[13][37] While initial response was partly appreciative, it was still considered dubious by some ultra-conservative printers who saw all sans-serif type as modern and unsound; one called it "typographical Bolshevism".[28][50] Sans-serifs were still regarded as vulgar and commercial by purists in this period: Johnston's pupil Graily Hewitt privately commented of them that:

In Johnston I have lost confidence. Despite all he did for us ... he has undone too much by forsaking his standard of the Roman alphabet, giving the world, without safeguard or explanation, his block letters which disfigure our modern life. His prestige has obscured their vulgarity and commercialism.[51]

Nonetheless, Gill Sans rapidly became popular after its release.

Gill Sans' technical production followed Monotype's standard method of the period. The characters were drawn mirrored on paper in large plan diagrams by the experienced drawing office team, led and trained by Pierpont and Fritz Steltzer, both of whom Monotype had recruited from the German printing industry.[52] The drawing staff who executed the design was disproportionately female; they worked out many aspects of the final drawings including adaptations of the letters to different sizes and the spacing.[53] The diagrams were then used as a plan for machining metal punches by pantograph to stamp matrices, which would be loaded into a casting machine to cast type.[52][54] It was Monotype's standard practice at the time to first engrave a limited number of characters and print proofs (some of which survive) from them to test overall balance of colour and spacing on the page, before completing the remaining characters.[18] Walter Tracy, Rhatigan and Gill's biographer Malcolm Yorke have all written that the drawing office's work in making Gill Sans successful has not been fully appreciated; Yorke described Gill as "tactless" in his claims that the design was "as much as possible mathematically measurable ... as little reliance as possible should be placed on the sensibility of the draughtsmen and others concerned in its machine facture".[18][28]

Reception

Gill Sans rapidly became very popular. Its success was aided by Monotype's sophisticated marketing, led by Gill's supporter Beatrice Warde, and due to its practicality and availability for machine composition in a very wide range of sizes and weights.[55][56]

Despite the popularity of Gill Sans, some reviews have been critical. Robert Harling, who knew Gill, wrote in his 1976 anthology examining Gill's lettering that the density of the basic weight made it unsuitable for extended passages of text, printing a passage in it as a demonstration.[45] The regular weight has been used to print body text for some trade printing uses such as guides to countryside walks published by the LNER.[57] William Addison Dwiggins described it and Futura as "fine in the capitals and bum in the lower-case" while proposing to create a more individualistic competitor, Metro, for Linotype around 1929.[58] Modern writers, including Stephen Coles and Ben Archer, have criticised it for failing to improve on Johnston and for unevenness of colour, especially in the bolder weights (discussed below).[59][20] More generally, modern font designer Jonathan Hoefler has criticised Johnston and Gill's designs for rigidity, calling their work "products more of the machine than the hand, chilly and austere designs shaped by unbending rules, whose occasional moments of whimsy were so out of place as to feel volatile and disquieting".[60]

Gill broached the topic of the similarity with Johnston in a variety of ways in his work and writings, writing to Johnston in 1933 to apologise for the typeface bearing his name and describing Johnston's work as being important and seminal.[51][61] However, in his Essay on Typography, he proposed that his version was "perhaps an improvement" and more "fool-proof" than Johnston's.[39] Johnston and Gill had drifted apart by the beginning of the 1920s, something Gill's groundbreaking biographer Fiona MacCarthy describes as partly due to the anti-Catholicism of Johnston's wife Greta.[62][63] Frank Pick, the Underground Electric Railways Company managing director who commissioned Johnston's typeface, privately thought Gill Sans "a rather close copy" of Johnston's work.[51]

Expansion and new styles

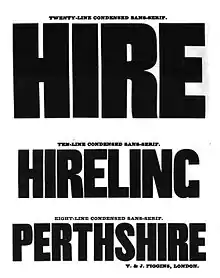

Following the initial success of Gill Sans, Monotype rapidly produced a wide variety of other variants.[18] In addition, Monotype sold moulds (matrices) for Gill Sans in very large sizes for their "Supercaster" type-casting equipment. Popular with advertisers, this allowed end-users to cast their own type at a very competitive price.[10][55] This made it a popular choice for posters. Gill's biographer Malcolm Yorke has described it as "the essence of clarity for public notices".[64]

Versions of Gill Sans were created in a wide range of styles such as condensed and shadowed weights.[18][65] Several shadowed designs were released, including a capitals-only regular shadowed design and a light-shadowed version with deep relief shadows. In the metal type era, a 'cameo ruled' design that placed white letters in boxes or against a stippled black background was available.[66][67][68][69] The shadowed weights were intended to be used together with the regular, printing in different colours, to achieve a simple multicolour effect.[70] Some of the decorative versions may predominantly have been designed by the Monotype office, with Gill examining, critiquing and approving the designs sent to him by post.[71] The long series of extensions, redrawings and conversions into new formats of one of Monotype's most important assets (extending long beyond Gill's death) has left Gill Sans with a great range of alternative designs and releases.[18] A book weight was created in 1993 in between the light and regular weight, suitable for body text, along with a heavy weight.[72]

Gill Kayo

.jpg.webp)

In 1936, Gill and Monotype released an extremely bold sans-serif named Gill Kayo (from KO, or knockout, implying its aggressive build). This has often been branded as Gill Sans Ultra Bold, though in practice many letters vary considerably from Gill Sans.[18] Gill, who thought of the design as something of a joke, proposed naming it "Double Elefans".[73][74] Harling reviewed it as "dismal" and sarcastically commented that "typographical historians of 2000AD (which isn't, after all, so very far away) will find this odd outburst in Mr Gill's career, and will spend much time in attempting to track down this sad psychological state of his during 1936."[75][76][77] Forty years later he described it as "the most horrendous and blackguardly of these display exploitations".[45] The design was begun in 1932;[18] some of the first drawings may have been prepared by Gill's son-in-law Denis Tegetmeier.[71] It made a return to popularity in the graphic design of the 1970s and 80s, when Letraset added a condensed weight.[78][79][80][81]

The boldest weights of Gill Sans, including Kayo, have been particularly criticised for design issues such as the eccentric design of the dots on the "i" and "j", and for their extreme boldness.[59][8] (Gill Sans' standard weight is, as already noted, already quite bold by modern standards.[59][28]) Gill argued in his Essay on Typography that the nineteenth-century tendency to make sans-serif typefaces attention-grabbingly bold was self-defeating, since the result was compromised legibility.[24] In the closing paragraph he ruefully noted his contribution to the genre:

There are now about as many different varieties of letters as there are different kinds of fools. I myself am responsible for designing five different sorts of sans-serif letters – each one thicker and fatter than the last because each advertisement has to try and shout down its neighbours.

Alternative characters

Monotype developed a set of alternative characters for Gill Sans to cater for differing tastes and national printing styles of different countries. These include Futura-inspired designs of "N", "M", "R", "a", "g", "t" and others, a four-terminal "W" in the French renaissance style, a tighter "R", a "Q" in the nineteenth-century style with a tail that looped upwards (similar to that on Century among others, and used by the LNER), oblique designs as opposed to the standard true italic, a more curving, true-italic "e" and several alternative numerals.[18][82][83][84][85] In particular, in the standard designs for Gill Sans the numeral "1", upper-case "i" and lower-case "L" are all a simple vertical line, so an alternative "1" with a serif was sold for number-heavy situations where this could otherwise cause confusion, such as on price-lists.[59] (Not all timetables used it: for example, the L.N.E.R. used the simple version.[83]) Some early versions of Gill Sans also had features later abandoned, such as an unusual "7" matching the curve of the "9", a "5" pushing forwards, and a lower-case letter-height "0".[39]

Gill was involved in the design of these alternatives, and Monotype's archive preserves notes that he rethought the geometric alternatives.[18][21] With the increasing popularity of Futura Gill Sans was not alone in being adapted: both Erbar and Dwiggins' Metro would undergo what historian Paul Shaw has called a "Futura-ectomy" to conform to taste.[86] After Gill's death, Monotype created versions for the Greek and Cyrillic alphabets.[lower-alpha 10] Monotype also added additional features not found in the metal type, notably text figures and small capitals.[5]

Series and styles

According to Rhatigan and other sources, by the end of the metal type period Gill Sans had been released in the following styles (not all sold at the same time):

- Gill Sans Titling (1928, series 231)

- Gill Sans (1930, series 262, sometimes called Gill Sans Medium)

- Gill Sans Bold (1930, series 275)

- Gill Sans Shadow Line (1931, series 290)[lower-alpha 11]

- Gill Sans Shadow Titling (1931, series 304)[lower-alpha 12]

- Gill Sans Bold Titling (1931, series 317)

- Gill Sans Extra Bold (1931, series 321)

- Gill Sans Light (1931, series 362)[lower-alpha 13]

- Gill Sans Shadow (1932, series 338)[lower-alpha 14]

- Gill Sans Bold Condensed (1932, series 343)

- Gill Sans 5pt (1932, series 349, sometimes called Gill Sans No. 2)[92]

- Gill Sans Bold 5pt (1932, series 350, sometimes called Bold No. 2)[92]

- Gill Sans Poster (1932, series 353)

- Gill Sans Bold Condensed Titling (1933, series 373)

- Gill Sans Cameo (1934, series 233)

- Gill Sans Cameo Ruled (1935, series 299)

- Gill Sans Shadow No. 1 (1936, series 406)[lower-alpha 15]

- Gill Sans Shadow No. 2 (1936, series 408)[lower-alpha 16]

- Gill Sans Ultra Bold (1936, series 442)

- Gill Sans Bold Extra Condensed (1937, series 468)

- Gill Sans Condensed (1937, series 485, sometimes called Medium Condensed)[18]

- Gill Sans Bold No. 3 (1937, series 575)

- Gill Sans Bold Condensed Titling (1939, series 525)

- Gill Sans Extra Bold Titling (1939, series 526)

- Gill Sans Light 5pt (1958, series 662, sometimes called Light No. 2)[92]

Titling series were capitals-only.

Phototypesetting

Monotype offered Gill Sans on film in the phototypesetting period. The fonts released in 1961 included Light 362, Series 262, Bold 275, Extra Bold 321, Condensed 343, all of which were released in film matrix sets "A" (6–7 points) and "B" (8–22, 24 points).[18][94]

Infant and rounded versions

Monotype created an infant version of Gill Sans using single-storey "a" and "g", and other more distinguishable characters such as a rounded "y", seriffed "1" and lower-case "L" with a turn at the bottom.[16][95] Infant designs of fonts are often used in education and toys as the letters are thought to be more recognisable to children being based on handwriting, and are often produced to supplement popular families such as Gill Sans, Akzidenz-Grotesk and Bembo.[96][97][98] Monotype also created a version with rounded stroke ends for John Lewis for use on toys.[99]

Digital releases

The digital releases of Gill Sans fall into several main phases: releases before 2005 (which includes most bundled "system" versions of Gill Sans), the 2005 Pro edition, and the 2015 Nova release which adds many alternative characters and is in part included with Windows 10.[16] In general characteristics for common weights the designs are similar, but there are some changes: for example, in the book weight the 2005 release used circular ij dots but the 2015 release uses square designs, and the 2015 release simplifies some ligatures.[16][100][101] Digital Gill Sans also gained character sets not present in the metal type, including text figures and small capitals.[5]

Like all metal type revivals, reviving Gill Sans in digital form raises several decisions of interpretation, such as the issue of how to compensate for the ink spread that would have been seen in print at small sizes more than larger. As a result, printed Gill Sans and its digital facsimile may not always match. The digital release of Gill Sans, like many Monotype digitisations, has been criticised, in particular for excessively tight letter-spacing and lack of optical sizes: with only one design released that has to be used at any text size, it cannot replicate the subtlety of design and spacing of the metal type, for which every size was drawn differently. In the hot metal era different font sizes varied as is normal for metal type, with wider spacing and other detail changes at smaller text sizes; other major sans-serif families such as Futura and Akzidenz-Grotesk are similar.[102][3] In the phototype period Monotype continued to offer two or three sizes of master, but all of this subtlety was lost on transfer to digital.[16][18][94] To replicate this, it is necessary to make manual adjustment to spacing to compensate for size changes, such as expanding the spacing and increasing the weight used at smaller sizes.[103][lower-alpha 17]

Former ATypI president John Berry commented of Gill Sans' modernised spacing that "both the regular weight and especially the light weight look much better when they're tracked loose".[105] In contrast, Walter Tracy wrote in 1986 that he preferred the later spacing: "the metal version ... was spaced, I suspect, as if it were a serif face".[106]

Gill Sans Nova (2015)

As of 2019, Monotype's current digitisation of Gill Sans is Gill Sans Nova, by George Ryan.[107] Gill Sans Nova adds many additional variants, including some of the previously undigitised inline versions, stylistic alternates and an ultra-light weight which had been drawn for Grazia.[16][108][109][110] The fonts differ from Gill Sans MT (MT stands for Monotype) in their adoption of the hooked 1 as default, while the regular weight is renamed 'Medium'. Monotype celebrated the release with a London exhibition on Gill's work, as they had in 1958 to mark the general release of Gill's serif design Joanna.[111][112][113][114] One addition was italic swash caps, which had been considered by Gill but never released.[16][115]

The family includes 43 fonts, including 33 text fonts in 9 weights and 3 widths, 6 inline fonts in 5 weights and 2 widths (1 in condensed), 2 shadowed fonts in 2 weights and 1 width, 1 shadowed outline font, 1 deco font. Characters set support includes W1G. The basic set of Regular, Light and Bold weights is bundled with Windows 10 in the user-downloadable "Pan-European Supplemental Fonts" package.[116]

Usage

First unveiled in a single uppercase weight in 1928, Gill Sans achieved national prominence almost immediately, when it was chosen the following year to become the standard typeface by the LNER railway company, soon appearing on every facet of the company's identity, from metal locomotive nameplates and hand-painted station signage to printed restaurant car menus, timetables and advertising posters.[48][117][118] The LNER promoted their rebranding by offering Gill (who was fascinated with railway engines) a footplate ride on the Flying Scotsman express service; he also painted for it a signboard in the style of Gill Sans, which survives in the collection of the St Bride Library.[10][83][119]

In 1949 the Railway Executive decided on standard types of signs to be used at all stations. Lettering was to use the Gill Sans typeface on a background of the regional colour.[120] Gill Sans was also used in much of its printed output, very often in capitals-only settings for signage. Specially drawn variations were developed by the Railway Executive (part of the British Transport Commission) for signs in its manual for the use of signpainters painting large signs by hand. Other users included Penguin Books' iconic paperback jacket designs from 1935 and British official mapping agency Ordnance Survey.[121] It was also used by London Transport for documents which could not be practically set in Johnston.[122] Paul Shaw, a historian of printing, has described it as a key element of the 'Modernist classical' style from the 1930s to the 1950s, that promoted clean, spare design, often with all-capitals and centred setting of headings.[123]

Gill Sans remains popular, although a trend away from it towards grotesque and neo-grotesque typefaces took place around the 1950s and 1960s under the influence of continental and American design.[124][125] Typefaces that became popular around this time included original early "grotesque" sans-serifs, as well as new and more elegant designs in the same style such as Helvetica and Univers. Mosley has commented that in 1960 "orders unexpectedly revived" for the old Monotype Grotesque design: "[it] represents, even more evocatively than Univers, the fresh revolutionary breeze that began to blow through typography in the early sixties."[126] He added in 2007 "its rather clumsy design seems to have been one of the chief attractions to iconoclastic designers tired of the ... prettiness of Gill Sans".[36][126] As an example of this trend, Jock Kinneir and Margaret Calvert's corporate rebranding of BR as British Rail in 1965 introduced Helvetica and Univers for printed matter and the custom but very similar Rail Alphabet for signage, and abandoned the classical, all caps signage style with which Gill Sans is often associated. Kinneir and Calvert's road signage redesign used a similar approach.[127][128][129] Linotype and its designer Hermann Zapf, who had begun development on a planned Gill Sans competitor in 1955, first considered redrawing some letters to make it more like these faces before abandoning the design project (now named "Magnus") around 1962–3.[130][131]

An additional development which reduced Gill Sans' dominance was the arrival of phototypesetting, which allowed typefaces to be printed from photographs on film and (especially in display use – hot metal continued for some body text setting for longer) massively increased the range of typefaces that could cheaply be used. Dry transfers like Letraset had a similar effect for smaller projects; their sans-serif Compacta and Stephenson Blake's Impact exemplified the design trends of the period by choosing dense, industrial designs.[132][133][134][135] Of the period from the 1930s to 1950s, when he was growing up, James Mosley would later write:

The Monotype classics dominated the typographical landscape ... in Britain, at any rate, they were so ubiquitous that, while their excellent quality was undeniable, it was possible to be bored by them and to begin to rebel against the bland good taste that they represented. In fact we were already aware by 1960 that they might not be around to bore us for too long. The death of metal type ... seemed at last to be happening.[136][lower-alpha 18]

While extremely popular in Britain, and to a lesser extent in European printing, Gill Sans did not achieve popularity with American printers in the hot metal era, with most preferring gothic designs like Franklin Gothic and geometric designs like Futura and Monotype's own Twentieth Century.[1][lower-alpha 19] Gill Sans therefore particularly achieved worldwide popularity after the close of the metal type era and in the phototypesetting and digital era, when it became a system font on Macintosh computers and Microsoft Office.[141] One use of Gill's work in the United States in this period, however, was a custom wordmark and logo made by Gill for Poetry magazine in 1930 based on Gill Sans. Its editor Harriet Monroe had seen Gill's work in London.[142]

_(cropped).JPG.webp)

The BBC adopted the typeface as its corporate typeface in 1997 for many but not all purposes, including on its logo.[143] Explaining the change, designer Martin Lambie-Nairn said that "by choosing a typeface that has stood the test of time, we avoid the trap of going down a modish route that might look outdated in several years' time".[144] This was not Gill's only association with the BBC, as he had designed sculptures and other artwork that are on display at the broadcaster's London headquarters, Broadcasting House.[145] In 2017, the BBC began to phase out Gill Sans in favour of a proprietary corporate font family, "Reith" (named after its first general manager John Reith), which was designed to be more legible on mobile devices, and did not require licensing for continued use.[146] The font was adopted by the BBC's corporate logo in 2021.[147]

Other more recent British organisations using Gill Sans have included Railtrack (and initially its successor Network Rail), John Lewis and the Church of England, which adopted Gill Sans as the typeface for the definitive Common Worship family of service books published from 2000.[148][149][150] British rock band Bloc Party has used Gill Sans in its logo.[151]

Notable non-British modern businesses using Gill Sans include United Colours of Benetton (which commissioned a custom variant), Tommy Hilfiger and Saab Automobile.[152][153][154][155] Many newer Mitsubishi elevator buttons use a derivative of the font, replacing Helvetica, as some numbers (such as "6" and "9") are more easily distinguishable.[156] Some old Express Lift buttons also use the font. In 2017, Roblox used Gill Sans Ultra Bold in their logo, albeit its letter "O" was stylized to a square, akin to a block.[157] AT&T used it until 2006, before changing it to Clearview after feeling that it was too in keeping with market research that people found the company "monolithic".[158] Edward Tufte, the information design theorist, uses Gill Sans on his website and in some of his published works.[159][160] Metro Transit uses Gill Sans Italic for the logos of its Metro lines, introduced in 2004 with the Hiawatha Line.[161][162] The Wikimedia Foundation uses Gill Sans on its wordmark. It is also used on VisualEditor.[163]

Until 2022, the Save the Children logo was used before switching to Lato.[164]

Similar fonts

Early competitors

.jpg.webp)

The Sheffield type foundry Stephenson Blake rapidly released a commercial competitor named Granby, influenced by Gill Sans, Johnston and Futura.[20][51][165] Granby was a large family with condensed and inline styles; it has a diamond-dot design like Johnston. It also included a "Granby Elephant" weight influenced by Gill Kayo.[166]

Another similar but more eccentric design was created by Johnston's student Harold Curwen for the use of his family company, the Curwen Press of Plaistow. Named "Curwen Sans" or "Curwen Modern", it has many similarities to Johnston also, and was occasionally used by London Transport in work printed by the Curwen Press.[167][168][169] Curwen described it as based on his time studying with Johnston in the 1900s, although it was not cut into metal until 1928, around the same time as Gill Sans was released, with a lower-case similar to that of Kabel.[51] A digitisation by K-Type was released in 2018.[170][171]

Several intended Gill Sans competitors were developed during the period of its popularity but ultimately did not see mass release. Jan Tschichold, who would later make extensive use of Gill Sans while designing books for Penguin, created a similar design for an early phototypesetting machine, which was at the time little-used but also since digitised.[172][173][174][20] During the 1930s Dutch type designer Jan van Krimpen, also a friend of Morison's, worked on a superfamily named Romulus, with serif and humanist sans-serif companion: the sans-serif, with a low x-height, never progressed beyond test proofs.[1] As described above, Linotype began work in 1955 on a Gill Sans competitor, intended to be named 'Magnus'.[lower-alpha 20] Designed by the German type designer Hermann Zapf with input from British Linotype manager Walter Tracy, the design was ultimately abandoned by 1963 for reasons of lack of manufacturing capacity and changing tastes, although it too reached test proofs.[8][130]

Besides similar fonts, many signs and objects made in Britain during the period of Gill Sans' dominance, such as the Keep Calm and Carry On poster, received hand-painted or custom lettering similar to Gill Sans.[175][176] Fighter Command during the war used a standard set of letters similar to it. Matthew Carter, later a prominent font designer, recalled in 2005 that when his mother cut linoleum block letters for him to play with during the Blitz they were based on it.[177][178] Another little-known follower was the NEN 3225 standard lettering, a project by the Dutch Standards Institute to create a set of standardised lettering for public use in the Netherlands, comprising a sans-serif similar to Gill Sans and a companion serif font drawn by Jan van Krimpen. The project was begun in 1944 but not published until 1963, and ultimately did not become popular.[179][180]

Later and digital-only designs

The category of humanist sans-serif typefaces, which Gill Sans helped to define, saw great attention during the 1980s and 1990s, especially as a reaction against the overwhelming popularity of Helvetica and Univers in the 1960s and 1970s.[20][181][182][183]

Modern sans-serif designs inspired by Gill often adapt the concept by creating a design better proportioned and spaced for body text, a wider and more homogeneous range of weights, something easier since the arrival of the computer due to the use of multiple master or interpolated font design, or more irregular and hand-drawn in style.[20][184] Jeremy Tankard's Bliss and Volker Küster's Today Sans are modern variations; Tankard commented on the genre's eclipse that his aim was to create "the first commercial typeface with an English feel since Gill Sans".[20][185][186] Rowton Sans is inspired by Gill but has a nearly upright italic, similar to that used by Gill in his serif font Joanna.[187][188] More distantly, Arthur Vanson's Chesham Sans is inspired by the British tradition of sans-serif signpainting, with many similarities to Gill's work.[189] Bitstream's Humanist 521 was an unofficial digitisation, to which its Russian licensee ParaType added a Cyrillic version in 1997.[190][191] The companies SoftMaker and Fontsite also released Gill Sans digitisations under different names including 'Chantilly', 'Gibson' and others.[192][193]

More loosely, Syntax by Hans Eduard Meier is similar in some ways. Released in 1968 and praised by Tschichold, it was intended to be a more dynamic, handwriting-influenced sans-serif form.[8][194] Its italic is, however, more of an oblique than Gill's.[5] Hypatia Sans, designed by Thomas Phinney and released by Adobe, was intended to be a more characterful humanist sans design.[195][196] Many other fonts are influenced by Gill Sans to some extent.[5][197]

Font superfamilies

A logical extension of the humanist sans-serif concept is the font superfamily: a serif font and a matching humanist sans-serif with similar letterforms. Martin Majoor's FF Scala Sans is a popular example of this influenced by Gill's work;[5][8] others include Charlotte Sans and Serif by Michael Gills for Letraset,[198] Mr and Mrs Eaves by Zuzana Licko, are based on Baskerville,[199][200] and Dover Sans and serif by Robin Mientjes, based on Caslon.[201][202] Monotype itself released Joanna Sans in 2015, as a screen-optimised sans-serif font intended to complement (but not exactly match) Gill's serif design Joanna.[203][204]

Legal aspects

Typeface designs are in many countries not copyrightable, and in others such as the United Kingdom, the design is out of copyright after the 70 years have passed since Gill's death in 1940, when the metal type family had been essentially completed.[18][205][206][207] That makes it legally permissible to create alternative digitised versions of Gill Sans although not necessarily of later Monotype additions to the font such as the book weight and euro sign. However, the name "Gill Sans" remains a Monotype trademark (no. 1340167 in the US) and therefore is not eligible to be used to name any derivative font.[208][209]

No complete direct open-source Gill Sans clone has yet been released. One of the most extensive is Gillius, a derivative by the Arkandis Digital Foundry project and designer Hirwen Harendal, which includes bold, italic, condensed and condensed bold styles. It is not a pure clone but rather is partly created by modifying Bitstream Vera and adds influences from geometric fonts that are particularly visible in the design of the "w".[210] K22, a foundry in Quezon City that is operated by the designer "Toto G", has released two Gill Sans shadowed variants as K22 EricGill Shadow (digitising the Gill Sans Shadow 338 design) and K22 EricGill Shadow Line, an inline variant, for free for "personal, private and non-commercial purposes" and for sale for commercial use.[211][212] A direct clone of the medium weight, Sans Guilt, was released by Brussels open source design group OSP in 2011, but it contains several obvious glitches such as misaligned "w" and "x" characters.[213]

Notes

- ↑ Although it is now common to classify Gill Sans and Futura as following separate directions in typeface design, humanist and geometric, this did not seem obvious to contemporary writers who often saw both as a new, more personalised development of the sans-serif letter. Some sources of the period distinguish sans-serifs into the "grotesques" of the nineteenth century and the modern "sans-serifs" of the twentieth, or similar classification structures.

- ↑ Mosley writes that it is "tempting to speculate" that this may have been Gill's idea even in the Johnston type, since it does not resemble Johnston's calligraphy, although there are naturally many past precedents for the design in signpainting and type.[10][11]

- ↑ Morison had argued for the theory that an oblique made a better match than an italic to an upright font through offering less of a contrast to it. This contention had been a major part of the protracted and tense development of the Perpetua project, begun before Gill Sans but released second, since Monotype management scrapped the oblique for a more normal italic.[14] Morison ultimately abandoned the idea and ruefully noted that Times New Roman had an italic that owed "more to Didot than dogma."[15]

- ↑ This is necessary since the slanting cut would unbalance the letter if the stroke weights were lighter.

- ↑ Cleverdon retained the book of alphabets, which also included model serif capitals and lower-case, before selling it to the Harry Ransom Center collection in 1967.[25]

- ↑ The sign-painter's alphabet had very small wedge serifs, similar to the capitals of Copperplate Gothic and similar designs. This style was occasionally used at the time. Johnston had considered it as a possible structure for the Underground alphabet and it was used on some variants of Johnston by the Underground with the involvement of Johnston's pupil Percy Delf Smith.[29]

- ↑ Some revivals of Johnston, such as a project by Berthold Wolpe, the ITC digitisation and that used by Transport for London have attempted to synthesise an italic or oblique for Johnston, but Johnston never created one.[40] P22's revival declined to add one.[41]

- ↑ This resulted in a design somewhat similar to Goudy Sans of a few years later. The development of Johnston had gone through a similar paring-down process a decade earlier, in which the idea of incorporating many calligraphy-influenced glyphs, like a capital-form "q" in the lower-case, was considered then abandoned.[8]

- ↑ An accessible specimen showing this is the Monotype Recorder article on the LNER timetable, which prints the sizes and weights the LNER favoured: stroke ends are visible on the 18 pt medium on "d", "p" and "q", but not at 10 pt.[48]

- ↑ Gerry Leonidas of the University of Reading, a leading expert on the history of Greek printing, has criticised Gill Sans' Greek characters, at least in versions up to 2002, as "seriously compromised" and unidiomatic, although he noted that it was nonetheless widely imitated around the 1950s.[87]

- ↑ Digitised in Gill Sans Nova as Gill Sans Nova Deco Regular.

- ↑ Digitised as Gill Sans Shadowed and Gill Sans Nova Shadowed Outline. Capitals-only, as a titling face.[88] Similar to Hans Bohn's Orplid face of a few years earlier.[89]

- ↑ Sometimes sold as Gill Sans Extra Light.[90]

- ↑ Could be combined with Gill Sans Regular printed in a different colour to achieve a shadowed effect.[91] By the late metal type period sold as Gill Sans Shadow No. 3, as the heaviest shadowed weight, despite being cut first.[92]

- ↑ The lightest Gill Sans Shadow weight, digitised as Gill Sans Light Shadowed and Gill Sans Nova Shadowed Light.[93]

- ↑ A slightly bolder shadowed weight.[93]

- ↑ Monotype's early digital releases of their classic typefaces, some unlike Gill Sans never fully revisited, were widely seen as erratic: Jonathan Hoefler commented sarcastically that "Gill Sans retired the trophy for 'Worst Digital Adaptation of an Okay Foundry Type', with Bembo & Centaur close behind".[104]

- ↑ A major part of Mosley's career in the period, indeed, was accumulating for St Bride Library metal type equipment from companies disposing of it.[137]

- ↑ Monotype's competitor Linotype was dominant in the American market at the time, which may have been a factor in this.[8][10] The shadow-effect capitals-only fonts appear in some US specimen brochures that otherwise excluded it in this period,[138][139] in particular the Cameo Ruled weight, which was sold by Baltimore Type Founders in its Airport family, otherwise a clone of Futura.[140]

- ↑ Britannia was also considered, but abandoned due to Stephenson Blake's pre-existing Britannic design.

References

- 1 2 3 Tracy, Walter (January 2003). Letters of Credit: A View of Type Design. D.R. Godine. pp. 87–98. ISBN 978-1-56792-240-0.

- ↑ Kupferschmid, Indra (13 May 2012). "Multi-axes type families". kupferschrift. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- 1 2 Gerstner, Karl (1963). "A new basis for the old Akzidenz-Grotesk (English translation)" (PDF). Der Druckspiegel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

[Futura and Gill Sans from] the nineteen-twenties are highly individual interventions in typeface development. They both bear the stamp of the people who designed them...Gill was attempting, ideally, to establish a link to tradition. He drew a sans-serif typeface, [like Renner with Futura] with the aid of the compass and ruler, but based on the visual regularity of a serif roman.

- ↑ Gerstner, Karl (1963). "Die alte Akzidenz-Grotesk auf neuer Basis" (PDF). Der Druckspiegel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Majoor, Martin (29 November 2004). "My Type Design Philosophy". Typotheque. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- 1 2 Nash, John. "In Defence of the Roman Letter" (PDF). Journal of the Edward Johnston Foundation. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- 1 2 Mosley, James (1964). "Trajan Revived". Alphabet. 1: 17–48.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Tam, Keith (2002). Calligraphic tendencies in the development of sanserif types in the twentieth century (PDF). Reading: University of Reading (MA thesis). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ Johnston, Edward (1906). Writing & Illuminating & Lettering. Macmillan. pp. 268–269, 384, 391.

- 1 2 3 4 Mosley, James (10 November 2015). Lecture on Gill's work (Speech). 'Me & Mr Gill' talk. Old Truman Brewery, London.

- 1 2 Mosley, James. "Eric Gill's R: the Italian connection". Type Foundry. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ↑ Rabinowitz, Tova (1 January 2015). Exploring Typography. Cengage Learning. pp. 127–9. ISBN 978-1-305-46481-0.

- 1 2 3 4 "Fifty Years of Typecutting" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 39 (2): 11, 21. 1950. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ↑ Allan Haley (15 September 1992). Typographic Milestones. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 91–98. ISBN 978-0-471-28894-7.

- ↑ Morison, Stanley (7 June 1973). A Tally of Types. CUP Archive. pp. 124–5. ISBN 978-0-521-09786-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rhatigan, Dan (10 November 2015). Lecture on the history of Gill Sans (Speech). 'Me & Mr Gill' talk. Old Truman Brewery, London.

- ↑ Rhatigan, Dan. "All about Workflow". Eye Magazine. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Rhatigan, Daniel (September 2014). "Gill Sans after Gill" (PDF). Forum (28): 3–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Budrick, Callie; Biemann, Emil (1961). "Subtleties of the Univers". Print. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Coles, Stephen. "Questioning Gill Sans". Typographica. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Eric Gill" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 41 (3). 1958. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ Coles, Stephen (2009). "A Cure for the Common Font". HOW.

[The] Light and Roman styles look pretty good on nearly anything. But it suffers from ubiquity…not to mention the dirty secret that many designers don't discover until it's too late: the family gets more and more awkward towards the heavy end of the spectrum.

- ↑ Specimen of Plain & Ornamental Types from the Foundry of V. & J. Figgins. 17 West St. Smithfield, London. 1845. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - 1 2 Gill, Eric (2007). "2: Lettering". An essay on typography. Boston: David R. Godine. pp. 40–47. ISBN 978-0-87923-950-3.

Mere weight and heaviness of letter ceases to be effective in assisting the comprehension of the reader when every poster plays the same shouting game ... a return to mere legibility seems desirable even if the effect be less striking.

- 1 2 Dreyfus, John; Cleverdon, Douglas (1987). A Book of Alphabets for Douglas Cleverdon. Wellingborough, England: Christopher Skelton. ISBN 978-0948906015.

- ↑ MacCarthy, Fiona (16 June 2011). Eric Gill. Faber & Faber. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-571-26582-4.

- ↑ Paul Townsend (20 October 2009). "Douglas Cleverdon Book Publishers". Flickr.com. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Yorke, Malcolm (2000). Eric Gill, man of flesh and spirit. London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 258–261. ISBN 978-1-86064-584-6.

- 1 2 Howes, Justin (2000). Johnston's Underground Type. Harrow Weald, Middlesex: Capital Transport. pp. 8, 20–21. ISBN 978-1-85414-231-3.

- ↑ Shewring, Walter, ed. (1948). The Letters of Eric Gill. Devin-Adair. pp. 435–8.

As perhaps you know, I was a pupil of Edward Johnston and was living almost next door to him when he was designing the LPTB sans-serif. It was a revolutionary thing and as you know, it redeemed the whole business of sans-serif from its nineteenth-century corruption. It was not until 1927 that I was asked by the Monotype Corporation to do a sans-serif for them.

- 1 2 Loxley, Simon (2005). "Chapter 9: Going Underground: Edward Johnston's Letters for London". Type: the secret history of letters. London: I. B. Tauris. pp. 109–121. ISBN 978-1-84511-028-4. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Simon Garfield (21 October 2010). Just My Type: A Book About Fonts. Profile Books. pp. 114–124. ISBN 978-1-84765-292-8.

- ↑ Mosley, James. "Eric Gill and the Cockerel Press". Upper & Lower Case. International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Mosley, James. "Eric Gill's Perpetua Type". Fine Print.

- ↑ Mosley, James (1989). "Eric Gill's Perpetua Type". In Ginger, E.M. (ed.). Fine Print on Type. Lund Humphries. pp. 54–58.

- 1 2 Mosley, James. "The Nymph and the Grot, an update". Type Foundry (blog). Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- 1 2 Barker, Nicolas (1972). Stanley Morison. London: Macmillan. pp. 218–286.

- ↑ Gill, Eric (1940). Eric Gill: an Autobiography. Lund Humphries. p. 220.

- 1 2 3 Gill, Eric. An Essay on Typography. p. 46.

- ↑ "ITC Johnston". fonts.com. Monotype. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ "P22 Underground pdf specimen". P22. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ "Gill Sans working drawing". St. Bride's Library. 13 January 2005. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ↑ Walters, John; Weinzierl, Terrance. "Terrance Weinzierl: Joanna Sans style and legacy". Monotype. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- 1 2 Handover, Phyllis Margaret (1958). "Grotesque Letters". Monotype Newsletter, Also Printed in Motif as "Letters Without Serifs".

- 1 2 3 Harling, Robert (1975). The Letter Forms and Type Designs of Eric Gill ([1st U.S. ed.]. ed.). Westerham, Kent: Published by Eva Svensson, and printed by the Westerham Press. pp. 36–48. ISBN 978-0-903696-04-3.

- ↑ Baines, Phil (7 January 2014). "Ditchling Museum of Art & Craft". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "Monument to Marchese Spinetta Malaspina". Victoria & Albert Museum. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- 1 2 Robinson, Edwin (1939). "Preparing a railway timetable" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 38 (1): 14–17, 24–26. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ Dan Rhatigan [@ultrasparky] (27 January 2012). "I am again stunned by the sheer amount of info in Monotype's archive. There's enough for a book just about the b, d, p, and q of Gill Sans" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ↑ Ashworth, Mikey (19 December 2015). "Sample page of Eric Gill's "Gill Sans" from The Fleuron, 1928". Flickr. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Howes, Justin (2000). Johnston's Underground Type. Harrow Weald, Middlesex: Capital Transport. pp. 73–78. ISBN 978-1-85414-231-3.

- 1 2 Rhatigan, Dan. "Time and Times again". Monotype. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ Savoie, Alice (1 December 2020). "The women behind Times New Roman". Journal of Design History. 33 (3): 209–224. doi:10.1093/jdh/epaa025.

- ↑ Morison, Stanley. "Changing the Times". Eye. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- 1 2 Badaracco, Claire (1991). "Innovative Industrial Design and Modern Public Culture: The Monotype Corporation, 1922–1932" (PDF). Business & Economic History. Business History Conference. 20 (second series): 226–233. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ Warde, Beatrice (1932). "Plumed Hats and Modern Typography". Commercial Art. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ↑ ""Rambles in ..." series, London and North Eastern Railway". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ↑ Shaw, Paul. "William Addison Dwiggins: Jack of All Trades, Master of More than One". Linotype. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Archer, Ben. "Eric Gill got it wrong; a re-evaluation of Gill Sans". Typotheque. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ "Ideal Sans". Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Derrick, Michael. "Book of the Week: The Ditchling Community". The Tablet. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ↑ MacCarthy, Fiona (1990). Eric Gill. London: Faber. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-571-14302-3.

- ↑ Loxley, Simon (31 March 2006). Type. Bloomsbury. pp. 161–3. ISBN 978-0-85773-017-6.

- ↑ Yorke, Malcolm (7 July 2000). Eric Gill: Man of Flesh and Spirit. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-86064-584-6.

- ↑ Rhatigan, Dan. "Gill Sans Extra Light". Instagram. Monotype via Instagram. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ Fuga, Giangiorgio (26 November 2007). "Riscatype 028029: Gill Sans specimen booklet 1938".

- ↑ Fuga, Giangiorgio (26 November 2007). "Riscatype 0030: Gill Sans specimen book 1938".

- ↑ "Gill Sans specimen book". Flickr photo of Gill Sans specimen book. Monotype. 3 December 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ "36 pt Gill Cameo Ruled". Hand & Eye Letterpress. 24 July 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ↑ "Gill Sans Shadow colours". Flickr. Monotype. 8 November 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- 1 2 Morris, Sallie (6 November 2015). Lecture on Gill's typefaces (Speech). 'Me & Mr Gill' talk. Old Truman Brewery, London.

- ↑ "The Monotype Chronicles: 1992–1996". Monotype. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ↑ "Signature Typeface". Eye. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ Yorke, Malcolm (7 July 2000). Eric Gill: Man of Flesh and Spirit. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-86064-584-6.

- ↑ "Kayo – also known as Gill Sans Ultra Bold". Stone Letters. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ Harling, Robert (1937). The Penrose Annual: Review of Graphic Arts, Volume 39 (1937). Lund Humphries.

Kayo [is] so fantastic as to take us immediately back to the dark ages of so much of nineteenth-century display typography. Kayo is a dismal type. In the hands of a skilful typographer it could probably be made to do a good-hearted, gargantuan job very well. In the hands of jobbing printers scattered throughout England it will be just plain murder. The type was originally named Double Elefans, which had a very pleasant touch of the lampoon about it. The new name, Kayo, is too horribly truthful.

- ↑ "Robert Harling: A Note". Stone Letters. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ↑ "Fonts in Use: Gill Kayo". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ↑ Devroye, Luc. "Kayo Poster". Luc Devroye. Monotype (original design). Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ Pitt, John. "Kayo – also known as Gill Sans Ultra Bold". Stone Letters. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ Coles, Stephen. "Gill Kayo". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- 1 2 Specimen Book of Monotype Printing Types. UK: Monotype. 6 January 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 Robinson, Edwin (1939). "Preparing a Railway Timetable" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 38 (1): 24. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ↑ Coles, Stephen (3 May 2014). "Royal System by Paul Cadovius logo and advertising". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ Coles, Stephen (21 March 2016). "Gill Sans Alts 362, 262, 275". Flickr. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ Shaw, Paul. "From the Archives: Typographic Sanity". Paul Shaw Letter Design. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Leonidas, Gerry. "A primer on Greek type design". Gerry Leonidas. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ↑ "Gill Sans Shadowed". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ↑ "Orplid". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ↑ Grießhammer, Frank (8 November 2015). "Gill Sans Extra Light Series 362". Flickr. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ↑ Grießhammer, Frank (8 November 2015). "Gill Sans Colour Series 338". Flickr. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Hunt, Paul D. (17 October 2007). "The Versatile Gill Family of Type Faces". Flickr. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Gill Sans Light Shadowed". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- 1 2 "The design of faces for 'Monophoto' film matrices" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 42 (2): 15–23. 1961. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ↑ "Gill Sans Infant". Fonts.com. Monotype. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Walker, Sue; Reynolds, Linda (1 January 2003). "Serifs, sans serifs and infant characters in children's reading books". Information Design Journal. 11 (3): 106–122. doi:10.1075/idj.11.2.04wal.

- ↑ "Akzidenz Grotesk Schoolbook". Berthold. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ "Bembo Infant". MyFonts. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Coles, Stephen; Rhatigan, Daniel (25 November 2013). "John Lewis Toys". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ "Gill Sans Pro". Fonts.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ Shaw, Paul. "Nova: a new Gill Sans for the DIY era". Design Observer. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ Frere-Jones, Tobias. "MicroPlus". Frere-Jones Type. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

[On adapting metal type designs to smaller sizes]: It was a kind of visual triage, where the essential features are defended and the less critical details are discarded. Each foundry had its own policy about how much to change and when, but the trends were always the same: lower contrast, looser spacing, simpler features.

- ↑ Sowersby, Kris (16 January 2013). "Playing Favourites, Part Two". Klim Type Foundry. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

I cannot stand any of the digital versions, they have something fundamentally wrong with them that I just can't put my finger on.

- ↑ Hoefler&Co. [@HoeflerCo] (17 January 2011). "@pauldhunt Gill Sans retired the trophy for "Worst Digital Adaptation of an Okay Foundry Type," with Bembo & Centaur close behind" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ↑ Berry, John D. (24 January 2005). "Cooling Magma". Creative Pro. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ Tracy, Walter (January 2003). Letters of Credit: A View of Type Design. D. R. Godine. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-56792-240-0.

- ↑ Shaw, Paul (2017). Revival Type: Digital Typefaces Inspired by the Past. Yale University Press. pp. 226–9. ISBN 978-0-300-21929-6.

- ↑ "Gill Sans Nova". Monotype. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ Walters, John. "George Ryan: The Gill Sans two-step". Monotype. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Hallmundur, Aegir. "Eric Gill Series". Typographica. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Steven, Rachael. "Monotype releases new Eric Gill collection". Creative Review. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ Brownlee, John (4 November 2015). "How Monotype Remastered Eric Gill for the 21st Century". Fast Co Design. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ Bennett, Neil. "Why we're not joining in the celebration of typographer Eric Gill". Digital Arts. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ "Monotype remasters classic Gill typeface for digital age". More About Advertising. 5 November 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ Bergmann, Christoph (21 December 2019). "Nenn mich Musik – The Düsseldorf Düsterboys". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ↑ Ding, Frederick (8 July 2015). "New fonts in Windows 10". Frederick's Timelog. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- 1 2 Skelton, Stephen. "Gill Sans" (PDF). New Writing. University of East Anglia. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ Cole, Beverley; Durack, Richard (1992). Railway Posters 1923–1947: From the Collection of the National Railway Museum, York. Laurence King Publishing. pp. 15–23. ISBN 978-1-85669-014-0.

- ↑ Hewitt, John (1995). "East Coast Joys: Tom Purvis and the LNER". Journal of Design History. 8 (4): 291–311. doi:10.1093/jdh/8.4.291. JSTOR 1316023.

- ↑ "Railway Station Signs. Standard Lettering". Warminster & Westbury journal, and Wilts County Advertiser. England. 20 May 1949. Retrieved 13 February 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Powell, Katie. "Ordnance Survey: not just paper maps". Creative Review. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ "Eiichi Kono on New Johnston". Creative Review. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Shaw, Paul. "The Univers of Helvetica: A Tale of Two Typefaces". Print. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ↑ Margolin, Victor (15 September 1989). Design Discourse: History, Theory, Criticism. University of Chicago Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-226-50514-5.

- ↑ Tracy, Walter (January 2003). Letters of Credit: A View of Type Design. D.R. Godine. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-56792-240-0.

- 1 2 Mosley, James (1999). The Nymph and the Grot. London. p. 9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Christopher, Elizabeth (3 September 2012). Communication Across Cultures. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-137-01097-1.

- ↑ Job, Nick. "Double Arrow blog". Double Arrow. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ Calvert, Margaret. "New Transport". A2-TYPE. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- 1 2 Nikolaus Julius Weichselbaumer (14 December 2015). Der Typograph Hermann Zapf: Eine Werkbiographie. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 170–3. ISBN 978-3-11-041505-6.

- ↑ Hermann Zapf: ein Arbeitsbericht. Hamburg: Maximilian-Gesellschaft. 1984. p. 74. ISBN 978-3-921743-28-7.

- ↑ "ITC Compacta". fonts.com. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- ↑ Dempsey, Mike. "Schmalfette: Tall, dark and handsome". Graphic Journey. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ↑ Dempsey, Mike. "Frederick Lambert: Graphic Design Britain". Design Journey. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ↑ Lee, Geoffrey. "Comments on Typophile thread". Typophile (archived). Archived from the original on 26 August 2005. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Mosley, James (2003). "Reviving the Classics: Matthew Carter and the Interpretation of Historical Models". In Mosley, James; Re, Margaret; Drucker, Johanna; Carter, Matthew (eds.). Typographically Speaking: The Art of Matthew Carter. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 31–34. ISBN 978-1-56898-427-8. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ↑ Barnes, Paul. "James Mosley: a life in objects". Eye magazine. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ↑ Barco Type Founders specimen brochure. Northlake, IL: Barco Type Founders. pp. 24, 31. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ Acme Type Specimen and Revised Price List (Catalog No. 6) (6 ed.). Chicago: Acme Type Foundry. 1947. p. 41. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ Devroye, Luc. "Baltimore Type Foundry". Type Design Information. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ↑ "Gill Sans MT in Microsoft products". Microsoft.com. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ Gehl, Paul. "100 Years of Poetry: Designing the Magazine, 1912–2012". Poetry. Poetry Magazine Foundation. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ "BBC Commissioning: Credits and branding". BBC. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ↑ Walker, Hayden. "BBC Logo: 1997–present". TV Ark. Archived from the original on 27 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Williams, Megan (24 January 2022). "Reckoning with Eric Gill's legacy". Creative Review. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ↑ Liptak, Andrew (6 August 2017). "The BBC is rolling out a new font designed for mobile screens". The Verge. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ↑ "BBC reveals new logos in modern makeover". BBC News. 19 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ Hitner, David. "StudioSmall on its ten-year partnership with fashion designer Margaret Howell". Creative Review. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Northover, Jim. "Letters that sell: a typographic history of UK department store John Lewis". Eye magazine. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Coles, Stephen (22 November 2012). "Church of England Common Worship Prayer Book, 2000". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Monotype [@Monotype] (1 November 2015). "Bloc Party used Gill Sans MT in its logo from 2004 to 2015. They've since switched to Gill Sans Light. #SetInGill" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ↑ Coles, Stephen (13 May 2015). "Tommy Hilfiger launch campaign and identity". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ↑ "Speak Up Archive: Saab or Dodgeball?". Underconsideration.com. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ Challand, Skylar. "Know Your Type: Gill Sans". IDSGN. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ Kyselý, Radek (30 May 2016). "Benetton identity redesign". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

Pentagram's redesign of Benetton's visual identity system ... includes a custom typeface based on Gill Sans, which was used previously by the brand. Benetton Sans was designed by Joe Finocchiaro. Key differences from Gill Sans include the normalized proportions of the caps, a straight-leg 'R', and more contemporary shapes for 'j, s, y'.

- ↑ Kazuko Matsuda and Masayuki Miyawaki. "Mitsubishi Electric Advance" (PDF). 99: 10–11. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Introducing Our Next-Generation Logo". Roblox Blog. 10 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ↑ Yaffa, Joshua (12 August 2007). "The Road to Clarity". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ↑ "Edward Tufte forum: What's your font?".

- ↑ "Edward Tufte forum: Tufte book fonts".

- ↑ Schuster, Rick. "Hiawatha Line Kiosks". www.think-graphics.com. THINK Graphic Design. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ "Metro Transit Brand Identity & Style Guide" (PDF). metrotransit.org. Metro Transit. 22 March 2021. p. 21. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ↑ "Visual identity guidelines". Wikimedia Foundation. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

The font Gill Sans (now Montserrat) is used to construct both the title and the descriptor of the mark.

- ↑ "Save the Children stops using font designed by paedophile artist". The Independent. 18 January 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ↑ Millington, Roy (2002). Stephenson Blake: The Last of the Old English Typefounders. Oak Knoll Press. pp. 170–175. ISBN 978-1-58456-086-9.

- ↑ Jackaman, Steve; Muir, Ashley. "Granby Elephant RRF". MyFonts. Red Rooster Fonts. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ "Typefaces in use at the Curwen Press, 1952". Curwen Press. 1952. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ↑ "Curwen Modern". Flickr. Curwen Press. 5 January 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ Curwen Sans type specimen. An Endless Supply. 2012. ISBN 978-0-9570614-1-5. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- ↑ Bates, Keith. "Reviving Curwen Sans". K-Type. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ↑ Bates, Keith. "Curwen Sans". K-Type. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ↑ Horn, Frederick A. (1936). "Gutenberg on his Metal: c". Art & Industry. pp. 42–3. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ Hollis, Richard (2006). Swiss graphic design: the origins and growth of an international style, 1920–1965. London: Laurence King. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-85669-487-2.

- ↑ "Tschichold". MyFonts. Presence Typo. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Bustillos, Maria. "The Vicious Trademark Battle Over 'Keep Calm and Carry On'". The Awl. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Hatherley, Owen (8 January 2016). "Keep Calm and Carry On – the sinister message behind the slogan that seduced the nation". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Howes, Justin (2000). Johnston's Underground Type. Harrow Weald, Middlesex: Capital Transport. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-1-85414-231-3.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Alex (28 November 2005). "Man of Letters". The New Yorker. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

Carter, his mother, and his younger brother were able to take little with them, and no toys that Carter remembers.To teach him to read, his mother cut an alphabet for him from linoleum. "Gill Sans", he says, "a popular typeface of the time".

- ↑ G. Willem Ovink (1964). "NEN 3225: Dutch Standard Alphabets". Alphabet. Kynoch Press. pp. 123–130.

- ↑ Jan Middendorp (2004). Dutch Type. 010 Publishers. pp. 298–9. ISBN 978-90-6450-460-0.

- ↑ Kupferschmid, Indra (9 November 2012). "Gill Sans Alternatives". Alphabettes. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ↑ Berry, John D. (22 July 2002). "Not Your Father's Sans Serif". Creative Pro. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ↑ Berry, John D. (5 August 2002). "The Human Side of Sans Serif". Creative Pro. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ↑ Butterick, Matthew. "Alternatives to Gill Sans". Typography for Lawyers (archived). Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

Gill Sans lit the way for other sans serif fonts that combine geometric precision with looser hand-drawn features, like Mr Eaves, FF Scala Sans, and FF Quadraat Sans.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Tankard, Jeremy. "Bliss Pro". Jeremy Tankard Typography. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ↑ Neil Macmillan (2006). An A-Z of Type Designers. Laurence King Publishing. pp. 26–7. ISBN 978-1-85669-395-0.

- ↑ Coles, Stephen. "New Arrivals – December 2014". Identifont. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ "Rowton Sans". MyFonts. FontYou. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Vanson, Arthur. "LHF Chesham Sans". Letterhead Fonts.

- ↑ "Humanist 521". MyFonts. ParaType. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ "Humanist 521". MyFonts. Bitstream. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ "Chantilly". FontSpring. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ "Chantilly Serial". MyFonts. Monotype. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ de Jong, Cees; Purvis, Alston W.; Friedl, Friedrich (2005). Creative Type: A Sourcebook of Classic and Contemporary Letterforms. Inmerc. pp. 148–151. ISBN 978-90-6611-250-6.

- ↑ Phinney, Thomas. "Hypatia Sans Pro, my new typeface". Typekit Blog. Adobe Systems. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ↑ "Hypatia Sans Pro". Fontspring. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ↑ Hall, Emma Christine (16 January 2018). "When is #timesup coming for Eric Gill". The Frontispiece. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ↑ "Charlotte Sans". MyFonts. Letraset. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ "Mr Eaves". Emigre Graphics. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ "Mr Eaves (pdf specimen)". Emigre Graphics. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ "Dover". Robin Mientjes. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ↑ Papaelias, Amy. "Dover Text". Typographica. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ↑ Boyd, Natalie. "Monotype's Eric Gill Series". How Design. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Weinzierl, Terrance. "Joanna Sans Nova MT". MyFonts. Monotype. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (c. 48), § 54 (England)

- ↑ Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000 (Ireland), §§ 84–85. Accessed 31 January 2013.

- ↑ Raustiala, Kal; Sprigman, Christopher (15 August 2012). The Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Innovation. Oxford University Press. pp. 130–135. ISBN 978-0-19-991176-9.

- ↑ Lawrence D. Graham (1999). Legal Battles that Shaped the Computer Industry. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-1-56720-178-9.

- ↑ "GILL SANS - Trademark Details". Justia. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ "ADF Fonts". Arkandis Digital Foundry.

- ↑ Devroye, Luc. "Toto". luc.devroye.org. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ Toto G (22 March 2014). "K22 EricGill Shadow". K22 Fonts. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sans Guilt release" (PDF). OSP. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

Bibliography

- Carter, Sebastian. Twentieth Century Type Designers. W.W. Norton, 1995. ISBN 0-393-70199-9.

- Johnson, Jaspert & Berry. Encyclopedia of Type Faces. Cassell & Co, 2001. ISBN 1-84188-139-2.

- Ott, Nicolaus, Friedl Fredrich, and Stein Bernard. Typography and Encyclopedic Survey of Type Design and Techniques Throughout History. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. 1998, ISBN 1-57912-023-7.

- Ovenden, Mark. Johnston and Gill: Very British Types. Lund Humphries. 2016, ISBN 978-1-84822-176-5

External links

Metal type era publicity materials:

- 1928 showing, The Fleuron (shows the first rare alternate 'R' with shorter leg, 5 without a vertical and 7 with curving leg)

- Monotype Recorder, Winter 1933 special issue:

- 'The Story of Gill Sans' (Monotype Recorder, winter 1933)

- Use by the LNER (Monotype Recorder, winter 1933)

- Gill on the Flying Scotsman

- First showing of Kayo (1936): 1, 2

- Gill Sans posters: 1, 2

- Gill Sans Colour Series (example of using a regular and shadowed design together to achieve a multicolour effect)

- Gill Sans Ultra Light specimen

- Series numbers index (also listed in Rhatigan)

Design process:

Transport use:

- British Railways Standard Signs Manual (1948; for signpainters)

- Example compositions – British Railways almost always used all-caps settings where possible

- British Railways tourism poster for Shrewsbury – many were issued in the 1940s and 50s to this general design

- London Transport bus timetable, 1962 – while London Transport has historically used Johnston for signs, the more widely available Gill Sans was also often used for printed material