Global biodiversity is the measure of biodiversity on planet Earth and is defined as the total variability of life forms. More than 99 percent of all species[1] that ever lived on Earth are estimated to be extinct.[2][3] Estimates on the number of Earth's current species range from 2 million to 1 trillion, but most estimates are around 11 million species or fewer.[4] About 1.74 million species were databased as of 2018,[5] and over 80 percent have not yet been described.[6] The total amount of DNA base pairs on Earth, as a possible approximation of global biodiversity, is estimated at 5.0 x 1037, and weighs 50 billion tonnes.[7] In comparison, the total mass of the biosphere has been estimated to be as much as 4 TtC (trillion tons of carbon).[8]

In other related studies, around 1.9 million extant species are believed to have been described currently,[9] but some scientists believe 20% are synonyms, reducing the total valid described species to 1.5 million. In 2013, a study published in Science estimated there to be 5 ± 3 million extant species on Earth although that is disputed.[10] Another study, published in 2011 by PLoS Biology, estimated there to be 8.7 million ± 1.3 million eukaryotic species on Earth.[11] Some 250,000 valid fossil species have been described, but this is believed to be a small proportion of all species that have ever lived.[12]

Global biodiversity is affected by extinction and speciation. The background extinction rate varies among taxa but it is estimated that there is approximately one extinction per million species years. Mammal species, for example, typically persist for 1 million years. Biodiversity has grown and shrunk in earth's past due to (presumably) abiotic factors such as extinction events caused by geologically rapid changes in climate. Climate change 299 million years ago was one such event. A cooling and drying resulted in catastrophic rainforest collapse and subsequently a great loss of diversity, especially of amphibians.[13]

Drivers that affect biodiversity and help animals to resource energy

Habitat change (see: habitat fragmentation or habitat destruction) is the most important driver currently affecting biodiversity, as some 40% of forests and ice-free habitats have been converted to cropland or pasture.[14] Other drivers are overexploitation, pollution, invasive species, and climate change.

Measuring diversity

Biodiversity is usually plotted as the richness of a geographic area, with some reference to a temporal scale. Types of biodiversity include taxonomic or species, ecological, morphological, and genetic diversity. Taxonomic diversity, that is the number of species, genera, family is the most commonly assessed type.[15] A few studies have attempted to quantitatively clarify the relationship between different types of diversity. For example, the biologist Sarda Sahney has found a close link between vertebrate taxonomic and ecological diversity.[16]

Known species

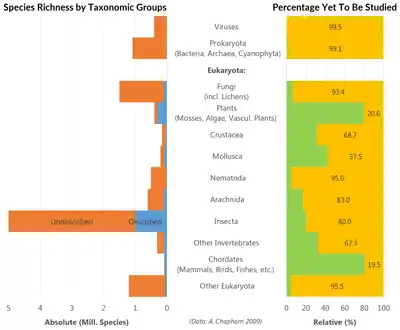

Chapman, 2005 and 2009[9] has attempted to compile perhaps the most comprehensive recent statistics on numbers of extant species, drawing on a range of published and unpublished sources, and has come up with a figure of approximately 1.9 million estimated described taxa, as against possibly a total of between 11 and 12 million anticipated species overall (described plus undescribed), though other reported values for the latter vary widely. It is important to note that in many cases, the values given for "Described" species are an estimate only (sometimes a mean of reported figures in the literature) since for many of the larger groups in particular, comprehensive lists of valid species names do not currently exist. For fossil species, exact or even approximate numbers are harder to find; Raup, 1986[18] includes data based on a compilation of 250,000 fossil species so the true number is undoubtedly somewhat higher than this. It should also be noted that the number of described species is increasing by around 18,000–19,000 extant, and approaching 2,000 fossil species each year, as of 2012.[19][20][21] The number of published species names is higher than the number of described species, sometimes considerably so, on account of the publication, through time, of multiple names (synonyms) for the same accepted taxon in many cases.

Based on Chapman's (2009) report,[9] the estimated numbers of described extant species as of 2009 can be broken down as follows:

| Major/Component group | Described | Global estimate (described + undescribed) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chordates | 64,788 | ~80,500 | ||

| ↳ | Mammals | 5,487 | ~5,500 | |

| ↳ | Birds | 9,990 | >10,000 | |

| ↳ | Reptiles | 8,734 | ~10,000 | |

| ↳ | Amphibia | 6,515 | ~15,000 | |

| ↳ | Fishes | 31,153 | ~40,000 | |

| ↳ | Agnatha | 116 | unknown | |

| ↳ | Cephalochordata | 33 | unknown | |

| ↳ | Tunicata | 2,760 | unknown | |

| Invertebrates | ~1,359,365 | ~6,755,830 | ||

| ↳ | Hemichordata | 108 | ~110 | |

| ↳ | Echinodermata | 7,003 | ~14,000 | |

| ↳ | Insecta | ~1,000,000 (965,431–1,015,897) | ~5,000,000 | |

| ↳ | Archaeognatha | 470 | ||

| ↳ | Blattodea | 3,684–4,000 | ||

| ↳ | Coleoptera | 360,000–~400,000 | 1,100,000 | |

| ↳ | Dermaptera | 1,816 | ||

| ↳ | Diptera | 152,956 | 240,000 | |

| ↳ | Embioptera | 200–300 | 2,000 | |

| ↳ | Ephemeroptera | 2,500–<3,000 | ||

| ↳ | Hemiptera | 80,000–88,000 | ||

| ↳ | Hymenoptera | 115,000 | >~1,000,000[22] | |

| ↳ | Isoptera | 2,600–2,800 | 4,000 | |

| ↳ | Lepidoptera | 174,250 | 300,000–500,000 | |

| ↳ | Mantodea | 2,200 | ||

| ↳ | Mecoptera | 481 | ||

| ↳ | Megaloptera | 250–300 | ||

| ↳ | Neuroptera | ~5,000 | ||

| ↳ | Notoptera | 55 | ||

| ↳ | Odonata | 6,500 | ||

| ↳ | Orthoptera | 24,380 | ||

| ↳ | Phasmatodea (Phasmida) | 2,500–3,300 | ||

| ↳ | Phthiraptera | >3,000–~3,200 | ||

| ↳ | Plecoptera | 2,274 | ||

| ↳ | Psocoptera | 3,200–~3,500 | ||

| ↳ | Siphonaptera | 2,525 | ||

| ↳ | Strepsiptera | 596 | ||

| ↳ | Thysanoptera | ~6,000 | ||

| ↳ | Trichoptera | 12,627 | ||

| ↳ | Zoraptera | 28 | ||

| ↳ | Zygentoma (Thysanura) | 370 | ||

| ↳ | Arachnida | 102,248 | ~600,000 | |

| ↳ | Pycnogonida | 1,340 | unknown | |

| ↳ | Myriapoda | 16,072 | ~90,000 | |

| ↳ | Crustacea | 47,000 | 150,000 | |

| ↳ | Onychophora | 165 | ~220 | |

| ↳ | non-Insect Hexapoda | 9,048 | 52,000 | |

| ↳ | Mollusca | ~85,000 | ~200,000 | |

| ↳ | Annelida | 16,763 | ~30,000 | |

| ↳ | Nematoda | <25,000 | ~500,000 | |

| ↳ | Acanthocephala | 1,150 | ~1,500 | |

| ↳ | Platyhelminthes | 20,000 | ~80,000 | |

| ↳ | Cnidaria | 9,795 | unknown | |

| ↳ | Porifera | ~6,000 | ~18,000 | |

| ↳ | Other Invertebrates | 12,673 | ~20,000 | |

| ↳ | Placozoa | 1 | - | |

| ↳ | Monoblastozoa | 1 | - | |

| ↳ | Mesozoa (Rhombozoa, Orthonectida) | 106 | - | |

| ↳ | Ctenophora | 166 | 200 | |

| ↳ | Nemertea (Nemertina) | 1,200 | 5,000–10,000 | |

| ↳ | Rotifera | 2,180 | - | |

| ↳ | Gastrotricha | 400 | - | |

| ↳ | Kinorhyncha | 130 | - | |

| ↳ | Nematomorpha | 331 | ~2,000 | |

| ↳ | Entoprocta (Kamptozoa) | 170 | 170 | |

| ↳ | Gnathostomulida | 97 | - | |

| ↳ | Priapulida | 16 | - | |

| ↳ | Loricifera | 28 | >100 | |

| ↳ | Cycliophora | 1 | - | |

| ↳ | Sipuncula | 144 | - | |

| ↳ | Echiura | 176 | - | |

| ↳ | Tardigrada | 1,045 | - | |

| ↳ | Phoronida | 10 | - | |

| ↳ | Ectoprocta (Bryozoa) | 5,700 | ~5,000 | |

| ↳ | Brachiopoda | 550 | - | |

| ↳ | Pentastomida | 100 | - | |

| ↳ | Chaetognatha | 121 | - | |

| Plants sens. lat. | ~310,129 | ~390,800 | ||

| ↳ | Bryophyta | 16,236 | ~22,750 | |

| ↳ | Liverworts | ~5,000 | ~7,500 | |

| ↳ | Hornworts | 236 | ~250 | |

| ↳ | Mosses | ~11,000 | ~15,000 | |

| ↳ | Algae (Plant) | 12,272 | unknown | |

| ↳ | Charophyta | 2,125 | - | |

| ↳ | Chlorophyta | 4,045 | - | |

| ↳ | Glaucophyta | 5 | - | |

| ↳ | Rhodophyta | 6,097 | - | |

| ↳ | Vascular Plants | 281,621 | ~368,050 | |

| ↳ | Ferns and allies | ~12,000 | ~15,000 | |

| ↳ | Gymnosperms | ~1,021 | ~1,050 | |

| ↳ | Magnoliophyta | ~268,600 | ~352,000 | |

| Fungi | 98,998 (incl. Lichens 17,000) | 1,500,000 (incl. Lichens ~25,000) | ||

| Others | ~66,307 | ~2,600,500 | ||

| ↳ | Chromista [incl. brown algae, diatoms and other groups] | 25,044 | ~200,500 | |

| ↳ | Protoctista [i.e. residual protist groups] | ~28,871 | >1,000,000 | |

| ↳ | Prokaryota [ Bacteria and Archaea, excl. Cyanophyta] | 7,643 | ~1,000,000 | |

| ↳ | Cyanophyta | 2,664 | unknown | |

| ↳ | Viruses | 2,085 | 400,000 | |

| Total (2009 data) | 1,899,587 | ~11,327,630 | ||

Estimates of total number of species

However the total number of species for some taxa may be much higher.

- 10–30 million insects;[23]

- 5–10 million bacteria;[24]

- 1.5 million fungi;[25]

- ~1 million mites[26]

- ~1 million protists[27][28]

In 1982, Terry Erwin published an estimate of global species richness of 30 million, by extrapolating from the numbers of beetles found in a species of tropical tree. In one species of tree, Erwin identified 1200 beetle species, of which he estimated 163 were found only in that type of tree.[29] Given the 50,000 described tropical tree species, Erwin suggested that there are almost 10 million beetle species in the tropics.[30] In 2011 a study published in PLoS Biology estimated there to be 8.7 million ± 1.3 million eukaryotic species on Earth.[11]

By 2017, most estimates projected there to be around 11 million species or fewer on Earth.[4] A 2017 study estimated there are around at least 1 to 6 billion species, 70-90% of which are bacteria.[4] A May 2016 study based on scaling laws estimated that 1 trillion species (overwhelmingly microbes) are on Earth currently with only one-thousandth of one percent described,[31][32] though this has been controversial and a 2019 study of varied environmental samples of 16S ribosomal RNA estimated that there exist 0.8-1.6 million species of prokaryotes.[33]

Indices

After the Convention on Biological Diversity was signed in 1992, biological conservation became a priority for the international community. There are several indicators used that describe trends in global biodiversity. However, there is no single indicator for all extant species as not all have been described and measured over time. There are different ways to measure changes in biodiversity. The Living Planet Index (LPI) is a population-based indicator that combines data from individual populations of many vertebrate species to create a single index.[34] The Global LPI for 2012 decreased by 28%. There are also indices that separate temperate and tropical species for marine and terrestrial species. The Red List Index is based on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and measures changes in conservation status over time and currently includes taxa that have been completely categorized: mammals, birds, amphibians and corals.[35] The Global Wild Bird Index is another indicator that shows trends in population of wild bird groups on a regional scale from data collected in formal surveys.[36] Challenges to these indices due to data availability are taxonomic gaps and the length of time of each index.

The Biodiversity Indicators Partnership was established in 2006 to assist biodiversity indicator development, advancement and to increase the availability of indicators.

Importance of biodiversity

Biodiversity is important for humans through ecosystem services and goods. Ecosystem services are broken down into: regulating services such as air and water purification, provisioning services (goods), such as fuel and food, cultural services and supporting services such as pollination and nutrient cycling.[37]

Biodiversity loss

_relative_to_baseline_-_fcosc-01-615419-g001.jpg.webp)

Biodiversity loss includes the worldwide extinction of different species, as well as the local reduction or loss of species in a certain habitat, resulting in a loss of biological diversity. The latter phenomenon can be temporary or permanent, depending on whether the environmental degradation that leads to the loss is reversible through ecological restoration/ecological resilience or effectively permanent (e.g. through land loss). The current global extinction (frequently called the sixth mass extinction or Anthropocene extinction), has resulted in a biodiversity crisis being driven by human activities which push beyond the planetary boundaries and so far has proven irreversible.[38][39][40]

The main direct threats to conservation (and thus causes for biodiversity loss) fall in eleven categories: Residential and commercial development; farming activities; energy production and mining; transportation and service corridors; biological resource usages; human intrusions and activities that alter, destroy, disturb habitats and species from exhibiting natural behaviors; natural system modification; invasive and problematic species, pathogens and genes; pollution; catastrophic geological events, climate change, and so on.[41]

Numerous scientists and the IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services assert that human population growth and overconsumption are the primary factors in this decline.[42][43][44][45][46] However other scientists have criticized this, saying that loss of habitat is caused mainly by "the growth of commodities for export" and that population has very little to do with overall consumption, due to country wealth disparities.[47]

Climate change is another threat to global biodiversity.[48][49] For example, coral reefs – which are biodiversity hotspots – will be lost within the century if global warming continues at the current rate.[50][51] However, habitat destruction e.g. for the expansion of agriculture, is currently the more significant driver of contemporary biodiversity loss, not climate change.[52][53]

International environmental organizations have been campaigning to prevent biodiversity loss for decades, public health officials have integrated it into the One Health approach to public health practice, and increasingly preservation of biodiversity is part of international policy, as part of the response to the Triple planetary crisis. For example, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity is focused on preventing biodiversity loss and proactive conservation of wild areas. The international commitment and goals for this work is currently embodied by Sustainable Development Goal 15 "Life on Land" and Sustainable Development Goal 14 "Life Below Water". However, the United Nations Environment Programme report on "Making Peace with Nature" released in 2020 found that most of these efforts had failed to meet their international goals.[54] Of the 20 biodiversity goals laid out by the Aichi Biodiversity Targets in 2010, only 6 were "partially achieved" by the deadline of 2020.[55][56]See also

References

- ↑ McKinney, Michael L. (6 December 2012). "How do rare species avoid extinction? A paleontological view". In Kunin, W. E.; Gaston, K. J. (eds.). The Biology of Rarity: Causes and consequences of rare—common differences. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 110. ISBN 978-94-011-5874-9.

- ↑ Stearns, Beverly Peterson; Stearns, Stephen C. (1999). Watching, from the Edge of Extinction. Yale University Press. p. x. ISBN 978-0-300-08469-6.

- ↑ Novacek, Michael J. (8 November 2014). "Prehistory's Brilliant Future". The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- 1 2 3 Larsen, Brendan B.; Miller, Elizabeth C.; Rhodes, Matthew K.; Wiens, John J. (September 2017). "Inordinate Fondness Multiplied and Redistributed: the Number of Species on Earth and the New Pie of Life". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 92 (3): 229–265. doi:10.1086/693564. ISSN 0033-5770. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ↑ "Catalogue of Life: 2018 Annual Checklist". 2018. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ↑ Mora, Camilo; Tittensor, Derek P.; Adl, Sina; et al. (23 August 2011). "How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean?". PLOS Biology. San Francisco, CA: PLOS. 9 (8): e1001127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 3160336. PMID 21886479.

- ↑ Nuwer, Rachel (18 July 2015). "Counting All the DNA on Earth". The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-07-18.

- ↑ "The Biosphere: Diversity of Life". Aspen Global Change Institute. Basalt, CO. Retrieved 2015-07-19.

- 1 2 3 Chapman, A. D. (2009). Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World (PDF) (2nd ed.). Canberra: Australian Biological Resources Study. pp. 1–80. ISBN 978-0-642-56861-8.

- ↑ Costello, Mark; Robert May; Nigel Stork (25 January 2013). "Can we name Earth's species before they go extinct?". Science. 339 (6118): 413–416. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..413C. doi:10.1126/science.1230318. PMID 23349283. S2CID 20757947.

- 1 2 Sweetlove, Lee (2011). "Number of species on Earth tagged at 8.7 million". Nature. Macmillan Publishers Limited. doi:10.1038/news.2011.498. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ↑ Donald R. Prothero (2013), Bringing Fossils to Life: An Introduction to Paleobiology (3rd ed.), Columbia University Press, p. 21

- ↑ Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J.; Falcon-Lang, H.J. (2010). "Rainforest collapse triggered Pennsylvanian tetrapod diversification in Euramerica". Geology. 38 (12): 1079–1082. Bibcode:2010Geo....38.1079S. doi:10.1130/G31182.1.

- ↑ Pereira, HM (2012). "Global Biodiversity Change: The Bad, the Good, and the Unknown". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 37: 25–50. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-042911-093511. S2CID 154898897.

- ↑ Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J. (2008). "Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1636): 759–65. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1370. PMC 2596898. PMID 18198148.

- ↑ Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J.; Ferry, P.A. (2010). "Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land". Biology Letters. 6 (4): 544–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024. PMC 2936204. PMID 20106856.

- ↑ Bautista, L.M.; Pantoja, J.C. (2005). "What animal species should we study next?" (PDF). Bulletin of the British Ecological Society. 36 (4): 27–28.

- ↑ Raup. D.M. (1986). "Biological extinction in earth history". Science. 231 (4745): 1528–1533. Bibcode:1986Sci...231.1528R. doi:10.1126/science.11542058. PMID 11542058. S2CID 23012011.

- ↑ IISE (2010). SOS 2009: State of Observed Species. Arizona State University: International Institute for Species Exploration. pp. 1–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-22. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- ↑ IISE (2011). SOS 2010: State of Observed Species. Arizona State University: International Institute for Species Exploration. pp. 1–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-22. Retrieved 2013-09-16.

- ↑ IISE (2012). SOS 2011: State of Observed Species (PDF). Arizona State University: International Institute for Species Exploration. pp. 1–14.

- ↑ Forbes, et al. (2018). "Quantifying the unquantifiable: why Hymenoptera, not Coleoptera, is the most speciose animal order". BMC Ecology. 18. doi:10.1186/s12898-018-0176-x. PMC 6042248.

- ↑ "Numbers of Insects (Species and Individuals)". Smithsonian Institution. 1996.

- ↑ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Census of Marine Life (CoML) BBC News

- ↑ David L. Hawksworth, "The magnitude of fungal diversity: the 1•5 million species estimate revisited" Mycological Research (2001), 105: 1422-1432 Cambridge University Press Abstract

- ↑ "Acari at University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Web Page". insects.ummz.lsa.umich.edu.

- ↑ Pawlowski, J. et al. (2012). CBOL Protist Working Group: Barcoding Eukaryotic Richness beyond the Animal, Plant, and Fungal Kingdoms. PLoS Biol 10(11): e1001419. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001419, .

- ↑ Adl, S. M. et al. (2007). Diversity, nomenclature, and taxonomy of protists. Systematic Biology 56(4), 684-689, .

- ↑ Erwin, Terry L. (March 1982). The Coleopterists Society (ed.). "Tropical Forests: Their Richness in Coleoptera and Other Arthropod Species". The Coleopterists Bulletin. 36 (1): 74–75. ISSN 0010-065X. JSTOR 4007977.

- ↑ Pullin, Andrew (2002). Conservation Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521644822. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Researchers find that Earth may be home to 1 trillion species". NSF. 2 May 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ↑ Locey, Lennon (2016). "Scaling laws predict global microbial diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (21): 5970–5975. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.5970L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1521291113. PMC 4889364. PMID 27140646.

- ↑ Louca, Stilianos; Mazel, Florent; Doebeli, Michael; Parfrey, Laura Wegener (4 February 2019). "A census-based estimate of Earth's bacterial and archaeal diversity". PLOS Biology. 17 (2): e3000106. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000106. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 6361415. PMID 30716065.

- ↑ "Indicators and Assessments Unit". Zoological Society of London.

- ↑ "Trends in the status of biodiversity". IUCN. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ↑ "Global Wild Bird Index". Biodiversity Indicators Partnership. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-11-25.

- ↑ De Groot, R.S.; et al. (2002). "A typology for the classification, and description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services". Ecological Economics. 41 (3): 393–408. doi:10.1016/s0921-8009(02)00089-7.

- 1 2 Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Beattie, Andrew; Ceballos, Gerardo; Crist, Eileen; Diamond, Joan; Dirzo, Rodolfo; Ehrlich, Anne H.; Harte, John; Harte, Mary Ellen; Pyke, Graham; Raven, Peter H.; Ripple, William J.; Saltré, Frédérik; Turnbull, Christine; Wackernagel, Mathis; Blumstein, Daniel T. (2021). "Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future". Frontiers in Conservation Science. 1. doi:10.3389/fcosc.2020.615419.

- ↑ Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Galetti M, Alamgir M, Crist E, Mahmoud MI, Laurance WF (13 November 2017). "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice". BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125. hdl:11336/71342.

Moreover, we have unleashed a mass extinction event, the sixth in roughly 540 million years, wherein many current life forms could be annihilated or at least committed to extinction by the end of this century.

- ↑ Cowie RH, Bouchet P, Fontaine B (April 2022). "The Sixth Mass Extinction: fact, fiction or speculation?". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 97 (2): 640–663. doi:10.1111/brv.12816. PMC 9786292. PMID 35014169. S2CID 245889833.

- ↑ "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ↑ Stokstad, Erik (6 May 2019). "Landmark analysis documents the alarming global decline of nature". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aax9287.

For the first time at a global scale, the report has ranked the causes of damage. Topping the list, changes in land use—principally agriculture—that have destroyed habitat. Second, hunting and other kinds of exploitation. These are followed by climate change, pollution, and invasive species, which are being spread by trade and other activities. Climate change will likely overtake the other threats in the next decades, the authors note. Driving these threats are the growing human population, which has doubled since 1970 to 7.6 billion, and consumption. (Per capita of use of materials is up 15% over the past 5 decades.)

- ↑ Pimm SL, Jenkins CN, Abell R, Brooks TM, Gittleman JL, Joppa LN, et al. (May 2014). "The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection". Science. 344 (6187): 1246752. doi:10.1126/science.1246752. PMID 24876501. S2CID 206552746.

The overarching driver of species extinction is human population growth and increasing per capita consumption.

- ↑ Cafaro, Philip; Hansson, Pernilla; Götmark, Frank (August 2022). "Overpopulation is a major cause of biodiversity loss and smaller human populations are necessary to preserve what is left" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 272. 109646. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109646. ISSN 0006-3207. S2CID 250185617.

Conservation biologists standardly list five main direct drivers of biodiversity loss: habitat loss, overexploitation of species, pollution, invasive species, and climate change. The Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services found that in recent decades habitat loss was the leading cause of terrestrial biodiversity loss, while overexploitation (overfishing) was the most important cause of marine losses (IPBES, 2019). All five direct drivers are important, on land and at sea, and all are made worse by larger and denser human populations.

- ↑ Crist, Eileen; Mora, Camilo; Engelman, Robert (21 April 2017). "The interaction of human population, food production, and biodiversity protection". Science. 356 (6335): 260–264. Bibcode:2017Sci...356..260C. doi:10.1126/science.aal2011. PMID 28428391. S2CID 12770178. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

Research suggests that the scale of human population and the current pace of its growth contribute substantially to the loss of biological diversity. Although technological change and unequal consumption inextricably mingle with demographic impacts on the environment, the needs of all human beings—especially for food—imply that projected population growth will undermine protection of the natural world.

- ↑ Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R. (2023). "Mutilation of the tree of life via mass extinction of animal genera". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 120 (39): e2306987120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12006987C. doi:10.1073/pnas.2306987120. PMC 10523489. PMID 37722053.

Current generic extinction rates will likely greatly accelerate in the next few decades due to drivers accompanying the growth and consumption of the human enterprise such as habitat destruction, illegal trade, and climate disruption.

- ↑ Hughes, Alice C.; Tougeron, Kévin; Martin, Dominic A.; Menga, Filippo; Rosado, Bruno H. P.; Villasante, Sebastian; Madgulkar, Shweta; Gonçalves, Fernando; Geneletti, Davide; Diele-Viegas, Luisa Maria; Berger, Sebastian; Colla, Sheila R.; de Andrade Kamimura, Vitor; Caggiano, Holly; Melo, Felipe (2023-01-01). "Smaller human populations are neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for biodiversity conservation". Biological Conservation. 277: 109841. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109841. ISSN 0006-3207.

Through examining the drivers of biodiversity loss in highly biodiverse countries, we show that it is not population driving the loss of habitats, but rather the growth of commodities for export, particularly soybean and oil-palm, primarily for livestock feed or biofuel consumption in higher income economies.

- ↑ "Climate change and biodiversity" (PDF). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ↑ Kannan, R.; James, D. A. (2009). "Effects of climate change on global biodiversity: a review of key literature" (PDF). Tropical Ecology. 50 (1): 31–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ "Climate change, reefs and the Coral Triangle". wwf.panda.org. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ Aldred, Jessica (2 July 2014). "Caribbean coral reefs 'will be lost within 20 years' without protection". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ Ketcham, Christopher (December 3, 2022). "Addressing Climate Change Will Not "Save the Planet"". The Intercept. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ↑ Caro, Tim; Rowe, Zeke; et al. (2022). "An inconvenient misconception: Climate change is not the principal driver of biodiversity loss". Conservation Letters. 15 (3): e12868. doi:10.1111/conl.12868. S2CID 246172852.

- ↑ United Nations Environment Programme (2021). Making Peace with Nature: A scientific blueprint to tackle the climate, biodiversity and pollution emergencies. Nairobi: United Nations.

- ↑ Cohen L (September 15, 2020). "More than 150 countries made a plan to preserve biodiversity a decade ago. A new report says they mostly failed". CBS News. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Global Biodiversity Outlook 5". Convention on Biological Diversity. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

External links

- Biodiversity A-Z Archived 2020-09-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Wikispecies

- Biodiversity—Global issues